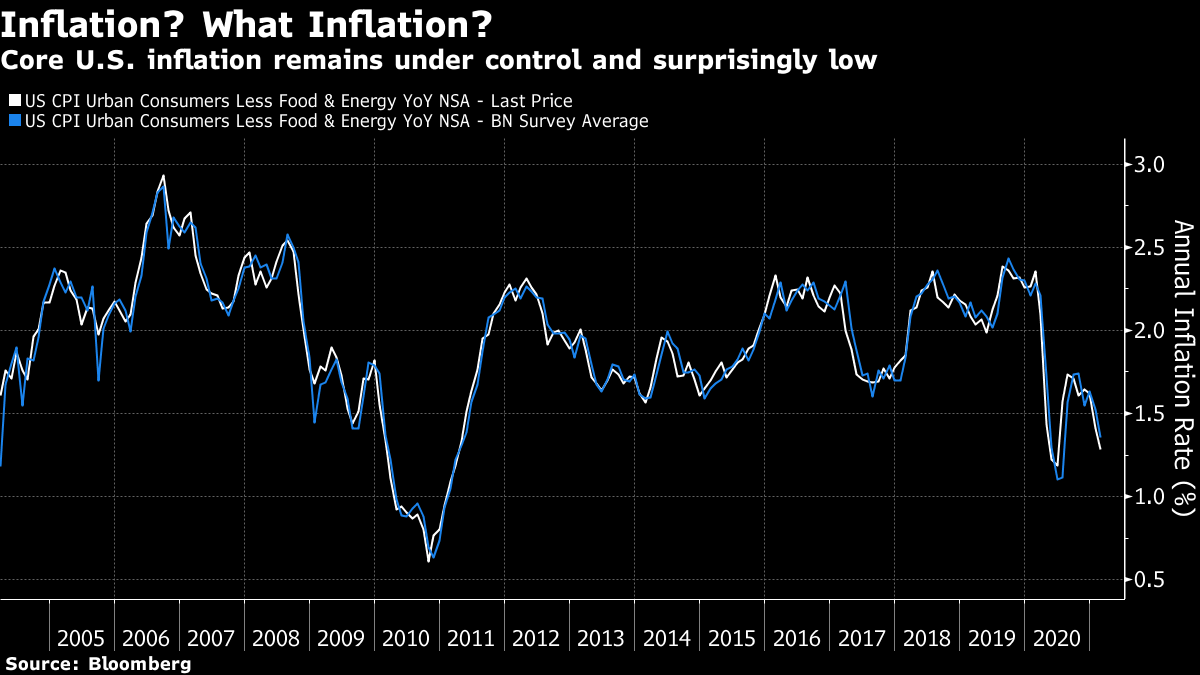

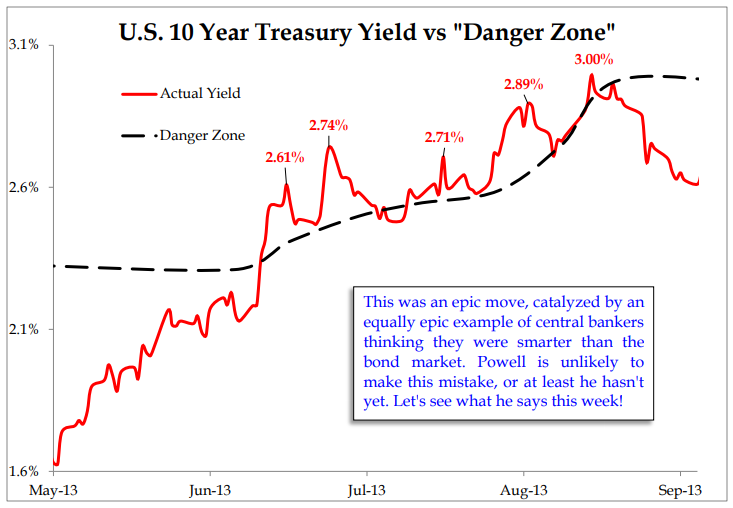

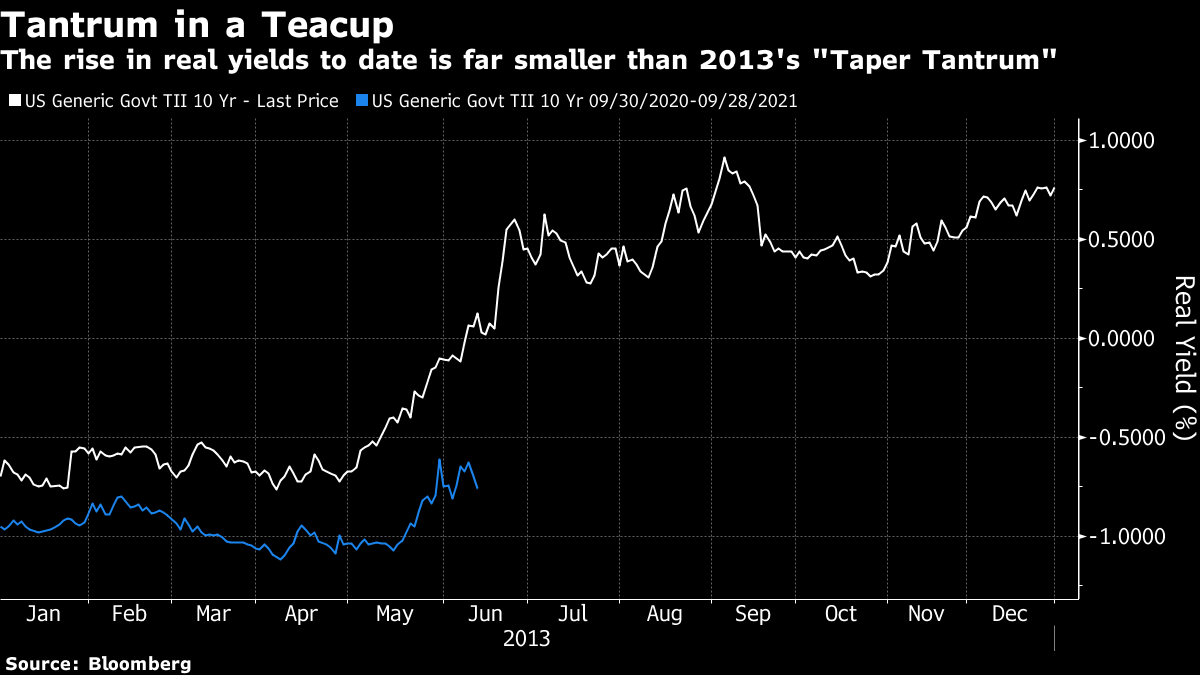

The Inflation ScareWhat exactly are we afraid of? It was always a safe bet that there would be an inflation scare at some point early this year. Just the base effects caused by the shutdown and the dive in the crude oil price 12 months ago more or less guaranteed that year-on-year comparisons would look scary for a while. But the scare has already started, at a point when actual figures don't look alarming in the slightest. This is Wednesday's reading for core U.S. consumer prices (excluding fuel and food). It was slightly lower than expectations:  As for the official market view, five-year breakevens have moved up to 2.5%. As the Federal Reserve wants inflation to run above 2% for an extended period, this is outright good news. Meanwhile five-year five-year forward breakevens suggest that the market is expecting prices to cool in the years from 2016, and average almost exactly 2%. That suggests positive reflation over the next few years, but not a return to a true inflationary regime and psychology:  Meanwhile, real yields remain negative. After a sharp rise in February, enough to have an effect on other markets, the U.S. 10-year real yield has declined again. Its trend still appears to be upward, but it is hard to call this a serious tightening of financial conditions:  If central banks do anything about this, it will be to try to put a thumb on the scale to push bond yields down again. Thursday's meeting of the European Central Bank has been preceded by much speculation about what actions the ECB might take, even though 10-year German bund yields remain firmly negative in both nominal and real terms. So where does the alarm come from? And where would inflation itself come from? The longer-term arguments rest on demographics, and in a historic shift in the Fed's priorities, to match the change in population trends and central bank priorities that ushered in the age of declining inflation 40 years ago. For long Points of Return discussions on these topics, see here and here. These arguments have to contend with the fact that improving technology has acted as a deflationary force for decades, and will probably continue to do so. These ideas are swirling around the investment world. But what has really driven the stock market rotation in recent weeks isn't a fear of inflation so much as a swift rise in bond yields. In the short term, this might engineer a selloff — but that is due to the mathematics of leveraged investing, rather than the discount rates for future cash flows. Tom Tzitzouris of Strategas Research Partners suggests that stocks have avoided an overall selloff because yields have barely touched what he describes as the "danger zone." He defines this using a "fair value" metric for yields which I covered earlier this year. On this definition, fair value is the expected cost of carry, which should generally be close to the consensus expectation of the neutral fed funds rate over 10 years. Tzitzouris's model posits that a danger zone is reached when the the actual yield exceeds this fair value by 15 basis points or more. And the market has shown a remarkable ability to flirt with that zone so far this year without going significantly far above it:  Compare and contrast with the infamous "taper tantrum" of 2013, when bond yields shot up in response to a shift in messaging from the Fed's Ben Bernanke. On that occasion, yields spent the better part of two months in Tzitzouris's danger zone. This led to an initial fall in U.S. stocks, and then to severe problems for a range of emerging markets:  Why does it work that way? Tzitzouris suggests it is because of the wide use of leverage. For leveraged investors using popular models based on value at risk, it needn't take a rise of more than 20 or 25 basis points to force them to close a position — which means selling stocks. That is what happens if the rise happens quickly. If the rise happens slowly, and remains below the danger zone, they can take evasive action by rotating toward stocks with cheaper valuations, rather than bailing out of equities altogether. The speed of the increase matters. So far, the rise in bond yields has been enough to force a big rotation within stocks, but not one at the level of asset classes, from equities back to bonds, Thinking through the intuition further, if a rise in bond yields is due to higher growth expectations (which is the case this time), and those expectations also raise expectations for future earnings, higher rates can be dealt with, at least in the models that investors use. When rates rise due to a change of philosophy by the Fed (as in the taper tantrum), or due to an attack by bond vigilantes, then this is much more damaging to the stock market. So far, this increase in bond yields hasn't been anything like 2013. This chart compares real 10-year yields then and now.  It is a fair guess that if real yields were continuing to move upward in a straight line, as they did in spring 2013, stocks would be staging quite a selloff. But they aren't. The latest inflation numbers helped stall the rise in bond yields for another day. The stock market's response was intriguing. After two days of dramatic switchbacks, the rotation out of growth and toward value continued, with tech companies falling again — and the average stock, as expressed by the S&P 500 equal-weighted index, hit an all-time high. So far this year, stocks have had a charmed existence, and bond investors have held back from engineering the kind of rise in yields that would force equity investors to the exit. The market excitement of the year has been a "yields scare" rather than an "inflation scare." For the short term, the great alarm was the possibility of a repeat of the bond selloff of 2013, and that has been — just about — avoided. For the longer term, inflation is much scarier. But it could be a while before we can discern the outlines of whether we truly have a secular shift toward higher inflation. In the meantime, it looks like stock investors will continue to ride their luck.

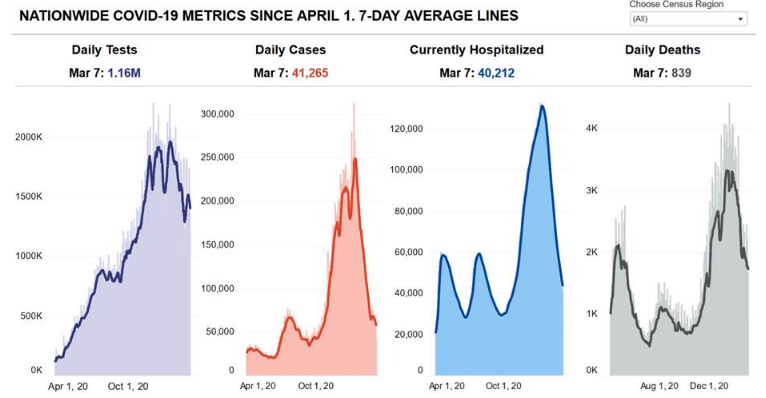

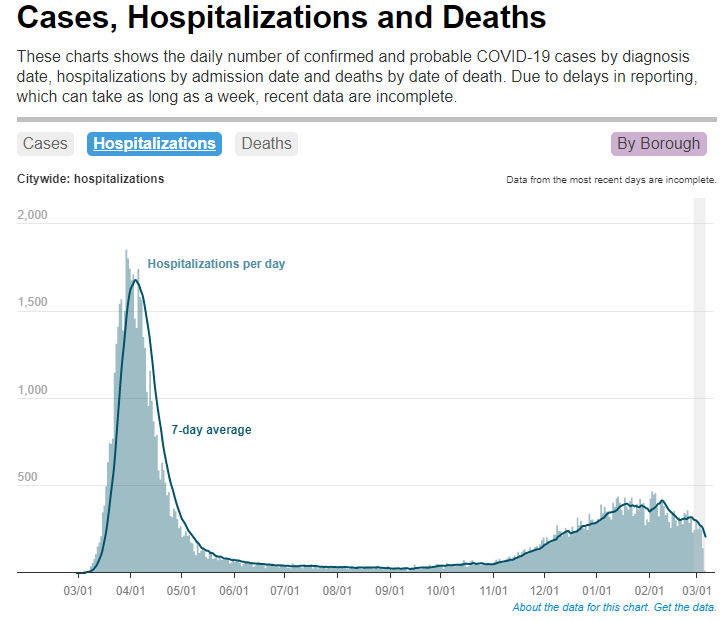

Covid-19: The Race Against TimeThe news on the pandemic is almost, but not quite, uniformly good. The vaccine rollout is getting going in earnest, and now appears to be exerting a downward push on the spread of the disease. On all measures followed by the Covid Tracking Project, the pandemic appears to be coming under control in the U.S.:  Further, the ability to keep people out of hospital is radically improved. Near to home, New York City suffered a terrible outbreak a year ago. The number of confirmed cases over the last few months actually topped the cases at the worst of the first wave. But this is what has happened to the number of hospitalizations:  Whatever the varying efficacy of the different vaccines, they are all almost equally good at keeping people from getting so ill that they need to go to hospital. There is, however, one area of concern to which all should be looking. Continental Europe, it is widely known, hasn't done a great job of distributing the vaccine so far. The contrast with the EU's recently departed member the U.K. might almost be funny if the consequences weren't potentially tragic (the chart comes from NatWest Markets):  If we include more countries, the EU looks worse, but the world's two most populous countries, China and India, look even more alarming:  This matters for two reasons. First, the longer a country waits until it has reached effective "herd immunity" — where the progress of the virus is stopped because it cannot find new bodies prone to infection — the longer it also has to wait until it can return to economic normality. Time taken over vaccines directly translates into lower GDP for this year. In many countries, as this chart from Bank of New York Mellon Corp. shows, restrictions on economic activity are almost as stringent as at the peak of the first wave:  A second reason for speed concerns the math of herd immunity. We don't yet know exactly how long immunity lasts, whether conferred by vaccine of suffering an infection. We will learn more about this in the next few months, but if immunity only lasts six months, then time is of the essence. Daniel Tenengauzer of Bank of New York Mellon Corp. offers the following arithmetic: Assuming a six-month immunity window, a pace of delivering one shot to 0.33% of the population each day would achieve 60% immunity after six months (0.33 * 182 = 60%). The range of vaccination pace would be as follows: 0.27% of the population getting one shot daily to reach 50% immunity within six months, or 0.41% of the population vaccinated daily to reach 75% immunity also within six months. The current vaccination pace stands at 1.1% of the population receiving daily vaccines in Israel and 0.68% in the UAE. For the U.K. it is also quite robust at 0.58% as it is in the U.S. at 0.54%. Additional countries at rates above 0.33% are Morocco, Chile and Turkey. In the Eurozone the pace remains sluggish, at 0.2% in Spain, 0.17% in Germany and 0.18% in France. Italy is even lower at 0.17%. Canada is at 0.15%.

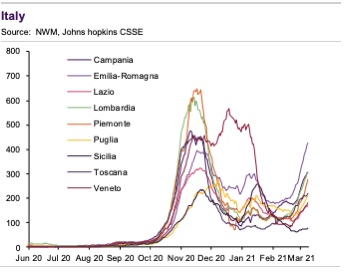

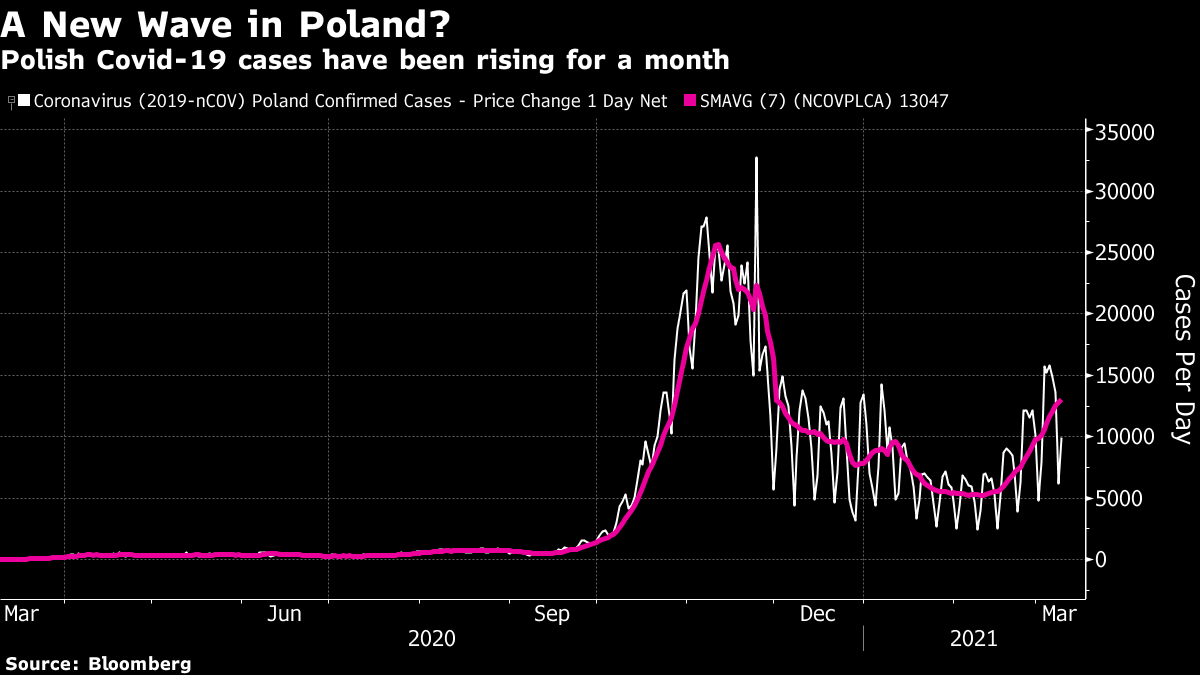

If herd immunity isn't achieved before early vaccine recipients begin to lose their immunity, then the chance to halt the virus in its tracks is lost. And there is no cause for complacency, because there are signs of another wave of the disease forming in Europe. The trend in cases is firmly downward for most of the continent, but this is the regional breakdown of new cases in Italy since last summer, as charted by NatWest using Johns Hopkins data:  We know the drill by now. These are cases, rather than deaths or hospitalizations. But the fact remains that cases are a leading indicator, and are plainly heading in the wrong direction, even as winter gives way to spring. Central Europe, which largely avoided the first wave last spring, gives greater cause for concern. Poland appears to be in the grip of a second wave:  Similar trends are also at work in Austria. Meanwhile the Czech Republic is suffering its third wave. Twice, promising attempts to snuff out the disease have come up short:  The odds that the pandemic will soon be relegated to the status of a mere irritant still look very good. But Covid-19 is adapting into new variants, and downside risks (financespeak for the possibility that many more people will die) remain. The financial good news is that there is still some upside ahead if the disease can be squelched in continental Europe in the next few months. The bad news is that we still need to keep a very close eye on the progress of cases and hospitalizations in Europe, and on the progress of the EU (and of the large emerging markets) in getting vaccines into arms. Survival TipsOn this subject, I urge all readers to get vaccinated if they possibly can. Today, I was lucky enough to have my second shot of Pfizer Inc. vaccine. Twelve hours later, at the time of writing, it's a little painful to lift my left arm much above the level of the shoulder, but other than that it's not the horrific ordeal that many are suggesting. Encouragingly, the process in New York was far more orderly, smooth and efficient than when I went in for my first shot three weeks ago. Going through the process reveals all the ways that this has been a baffling logistical puzzle. The banality of the final experience, with a brief and transitory pain as a tiny amount of liquid enters your muscle, can only leave you baffled with wonderment at the human ingenuity that brought us to this point. The end is in sight. The first few weeks of the vaccine rollout were punctuated by the same kind of anger and recriminations that we saw over hoarding at the beginning of the lockdown a year ago, amid allegations about queue-jumping and wasted shots. Now, judging by the atmosphere in New York, it's become more of a determined community effort to get rid of this thing and get our lives back. Any vaccine in the arm of any adult brings it closer. I doubt many Points of Return readers suffer from serious "vaccine hesitancy," but in case you are: Just do it. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment