| Programming note: Money Stuff will be off tomorrow, back on Monday. Goldman analyst surveyThis is pretty cheeky: Junior investment bankers at Goldman Sachs are suffering burnout from 100-hour work weeks and demanding bosses during a SPAC-fueled boom in deals, according to an internal survey done by a group of first-year analysts. The surge in activity has taken a serious toll on analysts' mental and physical health since at least the start of the year, according to slides released to social media and authenticated by people with knowledge of the matter. "The sleep deprivation, the treatment by senior bankers, the mental and physical stress ... I've been through foster care and this is arguably worse," one Goldman analyst said, according to the February survey of 13 employees. "My body physically hurts all the time and mentally I'm in a really dark place," another analyst said. The slide show, replete with color-coded charts and formatted in the official style of an investment banking pitch book, was created after a group of disgruntled analysts across several teams banded together to survey their colleagues, according to the people.

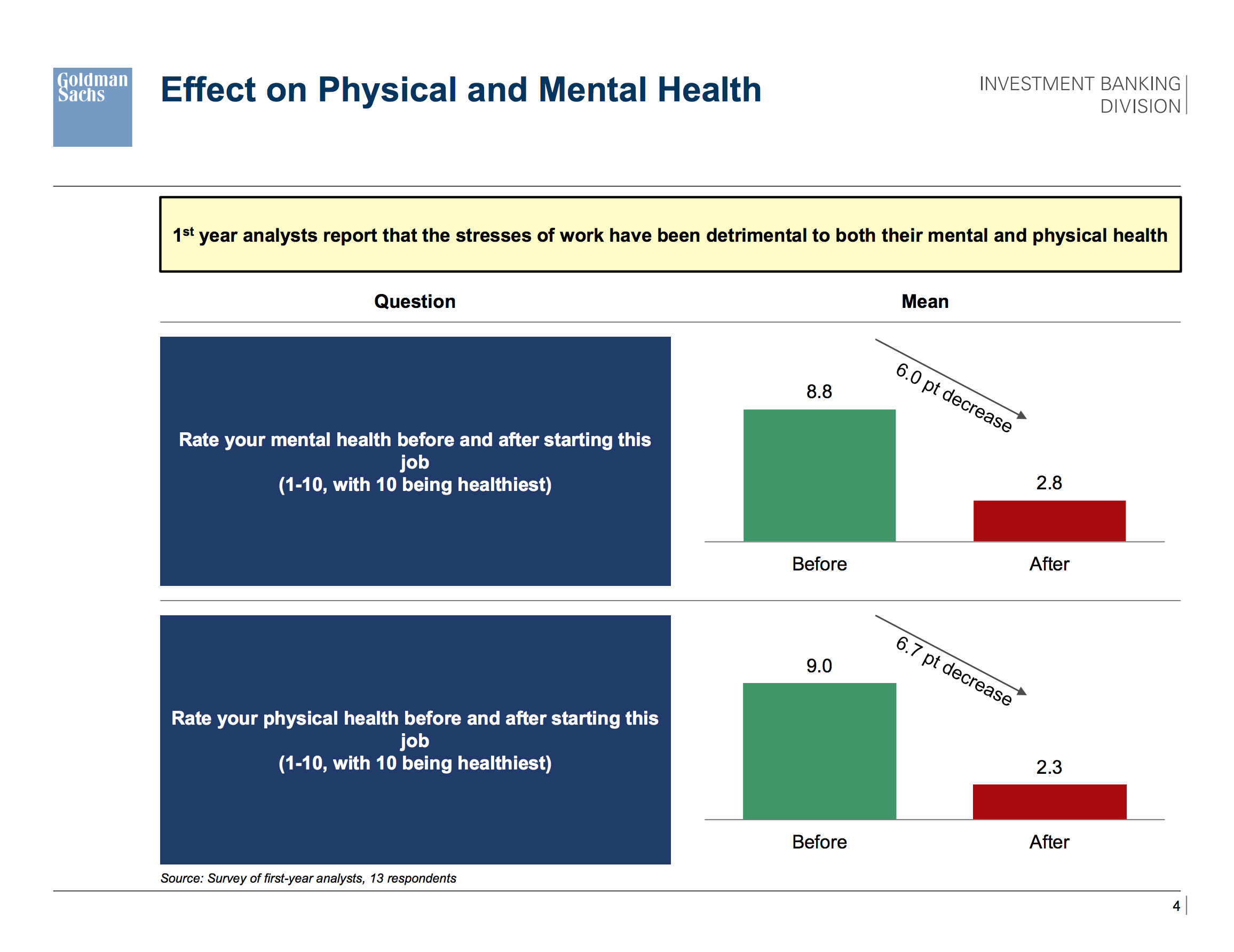

Here is the presentation. It looks very much like a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. presentation, with the proper colors and formatting and a little legal-boilerplate disclaimer at the bottom of the cover page saying that "Goldman Sachs does not provide accounting, tax, or legal advice." So this group of analysts, who (according to slide 2) work 105 hours a week and go to bed at 3 a.m., took time out of their "consistent 9am-5am" schedules that do not allow for "eating, showering or doing anything else" (slide 10) to write an 11-page slide deck in official Goldman Sachs style. There are somewhat comical bar charts, complete with source footnotes:  I kind of admire that?[1] Shows they're well-trained. The point of being an investment-banking analyst is to develop, through endless miserable repetition, a muscle memory for certain core skills. One of those skills — surely the least useful, but also the most salient — is formatting presentations. The other ones are, like, building financial models, talking confidently in meetings after limited hasty prep, etc., basic building-block skills of financial analysis that will serve former investment bankers well in a variety of future jobs. (Mostly private equity but still.) The presentation-formatting thing is totally dumb, but it is an easily legible signal, a brown M&M test of investment banking preparation. If you just automatically and instinctively build a properly formatted PowerPoint deck for everything,[2] people will trust you to build a leveraged buyout model or run due diligence on an acquisition. I'm sorry these analysts are sad and planning to leave Goldman, but at least they will leave with marketable skills. Anyway they're real sad. "How satisfied are you with this firm," the survey asks (slide 8), on a scale of 1 to 10 with 10 being the best; the median answer is 2. "How satisfied are you with your personal life" (slide 8) gets a median answer of 1. "How likely are you to recommend GS as a place to work to aspiring talent" (slide 9) gets an average answer of 4.2, which sounds exactly right: These analysts absolutely hate it, but they don't mind if other people experience it. The point of hazing is to make the victims of the hazing want to haze the next class of victims. Here are some "Select Analyst Quotes" (slide 10): "I can't sleep anymore because my anxiety levels are through the roof" "My body physically hurts all the time and mentally I'm in a really dark place" … "I didn't come into this job expecting a 9am-5pm's, but I also didn't expect consistent 9am-5am's either"

Disclosure, I used to work at Goldman and, you know what, sure. I was more senior than these analysts, and in a less demanding group; I was often mentally in a really dark place, but I never worked 105-hour weeks.[3] But I assumed that first-year investment banking analysts did. Or at least some of them did: Presumably this survey captured the 13 saddest analysts at Goldman and is therefore not necessarily representative. But I wouldn't be surprised if, for some of them, it was true. The last slide is about "Rectifying the Situation," with recommendations like "80 hours per week should be considered max capacity" and "for client meetings, teams should be pencils down 12 hours before the meeting." One benefit of putting together a well argued and properly formatted presentation is that, if you then present it to your bosses (!?!?!?), they might take it seriously: They shared their findings with managers. The grousing was serious enough that the Wall Street firm is enacting new measures, including forgoing some business to help keep the workload more manageable, according to a Goldman executive with knowledge of the matter.

Though I am not sure that that is the right analysis. Maybe the right analysis is: If you put together a horrifying presentation that really looks like an official Goldman Sachs deck, and then share it on social media, it will go viral and your bosses will have to take it seriously. We talked yesterday about complaints from junior employees at Apollo Global Management Inc., which were very much in the same vein, i.e. "we work too hard and often pointlessly." What I said then is that what is bad for junior-employee lifestyle is generally good for the firm; the fact that everyone is working too hard means that there's a lot of lucrative work to do: "We recognize that our people are very busy, because business is strong and volumes are at historic levels," said Nicole Sharp, a spokeswoman for Goldman Sachs. "A year into Covid, people are understandably quite stretched, and that's why we are listening to their concerns and taking multiple steps to address them."

"Complaints of not having time to eat or shower, appearing in the deck, are at odds with the softer, kinder Wall Street that senior industry executives have presented in a bid to attract and retain talent," notes Bloomberg, but I wondered if that bid was only necessary because the money isn't what it used to be. It's possible that there has been a generational change, and that today's analysts will not put up with the old trade of personal life for money. (And will call attention to it on social media.) But it's also possible that this is all cyclical, and senior executives will go back to attracting talent with a harder, meaner Wall Street that makes a ton of money again. (Though Goldman has also been "keeping a lid on employee compensation after the banner year" of 2020, which isn't great for that pitch.) Some analysts won't want to give up eating, sleeping and showering just to be on constant live deals that make a ton of money for the firm and perhaps, eventually, indirectly, for them. Maybe others will. Elsewhere: "Goldman Sachs Seeks Volunteers for Move to West Palm Beach Digs." Penny stocksHere is an article about how penny stocks are bad, etc.: Penny stocks occupy a low-rent district of Wall Street, a world rife with fraud and chicanery where companies that don't have a viable product, or are mired in debt, often sell their shares. Traded on the lightly regulated over-the-counter, or O.T.C., markets, penny stocks face fewer rules about publishing information on financial results or independent board members. Wall Street analysts don't usually follow them. Major investors don't buy them. But last month, there were 1.9 trillion transactions on O.T.C. markets, an increase of more than 2,000 percent from a year earlier, according to data from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, a self-regulatory group that oversees brokerage firms. The lack of oversight makes penny stocks easy targets for scammers, which has long accounted for their unsavory reputation. But risk can also be a draw for thrill seekers or those who fear they've missed a market boom that is creating wealth all around them.

And: Just as they were in Mr. Belfort's heyday, penny stocks remain the backbone of schemes to part newbie traders from their cash.

And: Stock-touting technology changes with the times. Cold-calling went out, followed by faxes and email spam. Today, social media sites like Twitter and Reddit, which powered the rise of GameStop and other meme stocks, are the preferred method for building unwarranted hype.

And: "It's all just a pool filled with sharks," said Urska Velikonja, a law professor who studies securities regulation at Georgetown University Law Center. "It's where the unwary go to get eaten."

Is it? I feel like I read these articles a lot, and what they never feature is a quote from a retiree on a fixed income who was somehow talked into believing that, for instance, "Garb Oil & Power, which, despite its name, spotlighted its planned purchase of a manufacturer of marijuana pipes in one of its most recent business operation updates," was an attractive investment in the steady long-term cash flows of the marijuana-pipe industry. Maybe those people exist and are hard for reporters to reach, but all the actual quotes are from guys like this: Art Hutchinson, a 50-year-old construction services salesman in Fort Worth, has been making bets on penny stocks — companies that he acknowledges are "absolute garbage" — for about two years. And the activity he watches closely is increasingly being driven by social media, he said. "Everybody is on Twitter, whatever, these social media accounts, and they're all lying," he said. "They're preying upon people not doing any research on their own, or not understanding it."

I want to emphasize here that I am not cherry-picking this quote; there are not a dozen other people quoted in the article saying "well I just buy whatever I see recommended on Twitter, why would the nice people on Twitter steer me wrong?" I submit to you that every single person who trades penny stocks is like Art Hutchinson. For one thing, they are all 50-year-old construction services salespeople in Fort Worth. For another thing, they are all absolutely and correctly convinced that everyone touting penny stocks on the internet is lying, and that the stocks they buy are all garbage. For a third thing, they think that they are special because they are able to do their own research and understand it, unlike the completely imaginary rubes who just buy whatever Twitter tells them to. Penny-stock trading, for them, is a fun game of skill and chance, and the skill involved is specifically figuring out who is lying about what and why. It's like poker, an enjoyable gambling pastime that depends on the ability to spot deception, and that is more enjoyable precisely because you get to match wits with people trying to trick you. Penny stocks are where the extremely wary go to get eaten. Everything, I keep saying, is like this. Perhaps you could tell a story in 2018 about how millions of everyday Americans had become convinced of the transformative power of legalized cannabis and wanted to invest their live savings in speculative bets on tiny pre-revenue cannabis companies, I don't know. But in 2021 I think the story has to be "people are bored and gambling is fun, and some fraction of the gambling market has been captured by self-consciously stupid penny-stock speculation." (Other fractions have been captured by crypto, NFTs, meme stocks, etc.) Penny-stock scammers are not (just) running "schemes to part newbie traders from their cash"; they are also providing those newbie traders (and experienced traders) with entertainment in exchange for their cash. Penny stocks are a casino; sure your expectation is negative, but (1) you might win! and (2) the goal is to enjoy yourself, have fun with your friends, and exercise and develop your gambling skills, while losing. Are casinos a scheme to part gamblers from their cash? Yes, sure, of course they are, but they are also entertainment, and most gamblers understand that. Meanwhile if everyday Americans want to become convinced of the transformative power of something and invest their life savings in speculative bets on pre-revenue companies in that sector, electric-vehicle SPACs are right there! Eliot Brown at the Wall Street Journal had a great article the other day about how a bunch of electric-vehicle companies that went public by merging with special purpose acquisition companies have all "disclosed plans to surpass the $10 billion revenue mark within three years of launching sales and production," beating Google's record of eight years. Those plans are disclosed in official public presentations written by the managements of those companies and filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission; the SPACs are underwritten by big investment banks and sponsored by high-finance celebrities. If you want to risk your money on hyped speculative companies, it's really easy, and you don't have to bother with penny stocks. Penny stocks are for the people who really know what they want. Mutual-fund votingA thought experiment that people occasionally propose is: What if shares of economic ownership of public companies were traded separately from voting control of those companies? Like, each share of stock is a unit consisting of (1) a 0.0001%, or whatever, claim on the residual value of the corporation plus (2) 0.0001%, or whatever, of the power to elect directors of the company, vote on big actions like mergers, and vote on minor symbolic issues like non-binding shareholder proxy proposals. In this thought experiment, those two things would be separable; you could buy a share of stock, sell the vote and keep the economic ownership, or you could buy a share of stock, sell the economic ownership and keep the vote. What would happen? Well, some people would prefer to own fewer votes. Me, for instance: If I bought individual stocks (I don't), I would immediately sell my votes, because my voting power would be too tiny to possibly matter and I'd rather get like 50 cents for it. And in fact retail investors are notoriously unlikely to vote their stock; the Financial Times had a good article last week about how lots of special purpose acquisition companies have trouble completing their mergers because they have a lot of retail investors and they can't get them to vote for the deals. They don't vote against the deals either; they just don't vote, because retail investors, mostly quite sensibly, don't vote. But perhaps others too. It is not at all clear that it is rational for index funds to vote their shares, most of the time. An index fund is in the business of (1) owning all the stocks (2) as cheaply as possible. Its value proposition to investors is "we will give you the market return, which is very easy, so we will spend absolutely no money doing it, so your costs will be low." If you own 500, or 3,000, stocks, it costs a lot of money to hire an analyst to follow each one, understand its business and its finances, evaluate the performance of its board and officers, and come to a reasoned position on how to vote on each question in its proxy. Well, you might vote on some stuff, stuff that you can analyze at a macro level that applies to every company. You might have a blanket rule of voting against certain sorts of "bad governance" (staggered boards of directors, etc.), or voting for certain sorts of climate-change proposals, because you think that governance and climate change have systematic effects on your portfolio. But if an activist comes to you and says "we think that this company has been insufficiently aggressive in capturing market share in the underwater widget space, and we'd like to elect new directors with strong experience in that area, here are their resumes," you might reply: "Look, you have the wrong person, I had never heard of this company before you came in; sure I own a billion dollars' worth of its stock but that's just because I own every stock; I don't have time to talk to you about underwater widgets." There is an argument that index funds are just not very good voters, on a lot of questions; they do not have all the right incentives to get informed and maximize shareholder value. (There are other, weirder arguments that we talk about a lot, arguments that they have incentives to maximize something other than shareholder value: Because they own all the companies, index funds might want to do things like reduce competition between them rather than maximize each company's value.) Perhaps both they and others would be better off if they sold their votes to someone who cared more. Other people would prefer to have more votes. The obvious category here is activist investors: If you're an activist hedge fund that wants to change the company's board and management and strategic direction, what you do is (1) buy a lot of stock, but not that much stock, and then (2) try to persuade other shareholders to vote for your proposals. You don't buy that much stock mostly because you don't have limitless money, you are targeting big companies, and you don't want to risk your entire fund's capital on one bet. But if you could cheaply buy votes, rather than trying to persuade other shareholders, that would help you out a lot. Instead of walking into the office of an index fund and saying "we'd like you to vote for our slate of underwater widget experts" and hearing them respond "we have never heard of this company, we just own all the stocks," you could walk into their office and say "we'd like to buy your votes for 10 cents a share" and have them respond "oh sure that's better than what we were doing with them."[4] I suppose another category would be anti-activists. If you are the chief executive officer of a family business that is now a public company, and you don't want evil short-term activists to come in and mess up your company, you could just go around to all the index funds and retail investors and try to buy up their voting rights, so that you can maintain control of the company indefinitely even as other people hold the economic ownership. Of course that happens all the time now, sort of, in that companies regularly go public with dual-class share structures in which the founder-CEOs keep control of the majority of the votes even as they sell economic ownership. But that is a crude approach. One problem with it is that it is hard to price. When a private company wants to go public, its CEO will say "I want to keep control," and the banks will say "okay but it will cost you, investors disfavor dual-class stock," and the CEO will say "how much will it cost me," and the banks will say "I dunno." It is hard to get clear evidence about the value of votes.[5] Whereas if every company went public with single-class stock, but you could trade the votes, there'd just be market evidence of the value of those votes. And then founders could say "well, for a billion dollars, sure I'll sell votes," or "well, if it only costs me $100 million, I guess I'll keep the votes," or whatever it is. So you could imagine a market in which everyone — retail investors, index funds, activists, insiders — can buy economic exposure to companies, but they can also trade voting rights among themselves, so that the voting rights migrate from people who don't care about them and don't do a good job with them to people who do care and will do a good job. Now, there are obvious downsides to this idea. For one thing, that story I just told about the CEO is not a great story. A CEO gets a lot of benefits from her company. If she owns stock, she wants the stock to go up, because then she will get richer. But she also gets a salary, and a bonus, and a nice office, and maybe a corporate jet, and the satisfaction and prestige of being a CEO. A CEO with little economic ownership but a lot of voting control might do bad stuff: She might pay herself a lot, and not work very hard, and buy a lot of jets with company money, and the shareholders — whose money she was spending — wouldn't be able to do anything about it.[6] But you could do even worse. What about an activist short seller who bets a billion dollars on the company to fail, buys up 51% of the votes for $200 million, votes in a new slate of directors, appoints herself CEO, and announces "hey new strategic pivot, we have fired everyone, shut down production, and are now in the business of lighting all our money on fire until there is none left"? The stock goes to zero, the activist makes a billion dollars on her short and loses $200 million on her vote-buying; net, she is up $800 million. I think there are obvious deterrents to this — directors' fiduciary duties, etc. — but people do sometimes worry about "empty voting," about investors gaining control of a company without sharing the same economic interests as other shareholders, and doing bad stuff with it. I think on balance a pure market for shareholder votes would be bad, but I am not sure about that. Certainly it would have a market-completeness elegance to it that I, and others, are drawn to. And in fact in the absence of a real market for shareholder votes, there are various halfway solutions. Index funds own a lot of stock that they lend out to short sellers, getting paid a stock borrow fee and giving up votes they didn't care that much about anyway. Activists can buy physical stock (with votes) and sell it on swap (without votes) in order to maximize their votes without too much economic risk. Founders can go public with dual-class stock, giving up some (uncertain) valuation in exchange for voting control. Big shareholders can do "funded collars" in which they effectively sell a lot of their economic exposure to hedge risks and raise money, but keep the votes. There is a market for shareholder votes, or rather there are several markets for them, if you know where to look. Perhaps a simpler and more transparent market would be better, or at least an interesting experiment. I don't know. Anyway here's a speech from Allison Herren Lee, the acting chair of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, about how big mutual funds (1) should put more time and effort into voting their shares, (2) should vote more often for environmental, social and governance initiatives, and (3) should make better and clearer disclosures to their investors about how they vote. She refers specifically to the share lending thing: Take, for example, securities lending. Because index funds cannot sell out of their positions, proxy voting becomes a particularly important tool for maximizing value. But the economic benefits of voting are diffused among all shareholders, while index funds face their own economic pressure to lend out their shares, or not recall shares, instead of voting. These pressures can also present potential conflicts of interest for advisers in light of fee splits and revenue sharing that an adviser may receive. The revenue generated by securities lending can lower costs when passed back to investors – but this should be carefully balanced against, and potentially moderated by, the value to shareholders in exercising oversight of boards and management in the companies they own.

"Every Vote Counts: The Importance of Fund Voting and Disclosure," is the title of the speech, but does it? Is the right analysis that every shareholder should care equally about voting, and vote according to its own careful analysis and beliefs? Or is something more complicated going on? Bitcoin price impactI love this line from Bank of America Corp. research strategists: "What has created the enormous upside pressure on Bitcoin prices in recent years and, particularly, in 2020?" BofA asked. "The simple answer: modest capital inflows."

If you take out the word "modest," that's the most basic market tautology: The price went up because more people wanted to buy it. (The usual phrase, used mostly as a joke, is "more buyers than sellers.") But of course they put in the word "modest." The price went up because a couple of people wanted to buy a little of it, and it's very sensitive to that. It is a brutal, quiet dig at the size and efficiency of the Bitcoin market: "Bitcoin is extremely sensitive to increased dollar demand," the BofA strategists said in a note Wednesday. "We estimate a net inflow into Bitcoin of just $93 million would result in price appreciation of 1%, while the similar figure for gold would be closer to $2 billion or 20 times higher. In contrast, the same analysis for the 20-year-plus Treasuries shows that multibillion money flows do not have a significant impact on price, pointing to the much larger and stable nature of the U.S. Treasuries markets." ... BofA notes that since about 95% of total Bitcoin is owned by the top 2.4% of addresses with the largest balances, it's "impractical as a payments mechanism or even as an investment vehicle."

But that makes it a good speculative vehicle: There just isn't very much of it for sale, so the price is very sensitive to relatively small events, so it's exciting. Things happenCredit Suisse's supply chain funds missed out on SoftBank injection. At Long Last, Wall Street Sees Path to Return to the Office. Apollo, Caesars, and Wall Street's 'Billionaire Brawl' for Control of a Gaming Empire. What Happened When American Investors Tried to Buy the World's Oldest Bank. America's Covid Swab Supply Depends on Two Cousins Who Hate Each Other. FCA launches proceedings against NatWest over alleged money laundering. Morgan Stanley to Offer Rich Clients Access to Bitcoin Funds. "Trading as a service." Fleetwood Mac skateboard video NFT. Dozens change name to 'salmon' to get sushi deal in Taiwan. If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! [1] Those charts would be funnier if the little arrows were labeled with a CAGR rather than an absolute decrease, but that is a small nit. [2] Incidentally when I worked at Goldman, PowerPoint was pretty rarely used, and decks like this were mostly created in Microsoft Word. I assume that's still true. To this day I have no real idea how to use PowerPoint. PowerPoint is the norm elsewhere, though, and it's easier and more normal to say "PowerPoint deck." [3] In fact I came to Goldman as a lifestyle move; at my previous job 105-hour weeks were much more the norm. [4] In actual fact activists sometimes do the *opposite* of this, accumulating more economic ownership than votes, because of various antitrust and securities-law regimes that restrict beneficial ownership. So they'll buy economic exposure via swaps, cash-settled options, etc., in order to increase their ownership without voting rights, and then just work extra hard to convince people to vote with them. [5] You can get *unclear* evidence. Some companies have high-vote and low-vote stocks that both trade, so you can see if the high-vote stock trades at a premium. But often (1) the high-vote stock is less liquid, so it trades at a discount, and (2) a majority of the high-vote stock is concentrated in one controlling shareholder, so the publicly traded high-vote stock doesn't actually confer that much actual power. Meanwhile at lots of the most-controlled companies, the high-vote stock simply doesn't trade; often, the company's charter provides that if the controlling shareholders sell it it automatically converts into low-vote stock. So there's no clear way to evaluate how much the voting control there is worth. And it's possible that it's negative; it's possible that shareholders in, say, Facebook Inc. like Mark Zuckerberg so much that they'd rather defer to him on all corporate decisions than have the power to make those decisions themselves. [6] Of course this is true of all those dual-class companies, but most of them are either (1) run by founders who do in fact have enormous economic stakes and strong intrinsic motivation or (2) family firms, quasi-public trusts, etc., where the executives also have some sort of intrinsic motivation. If any old public-company CEO could just go around buying votes, you might get more abuses. |

Post a Comment