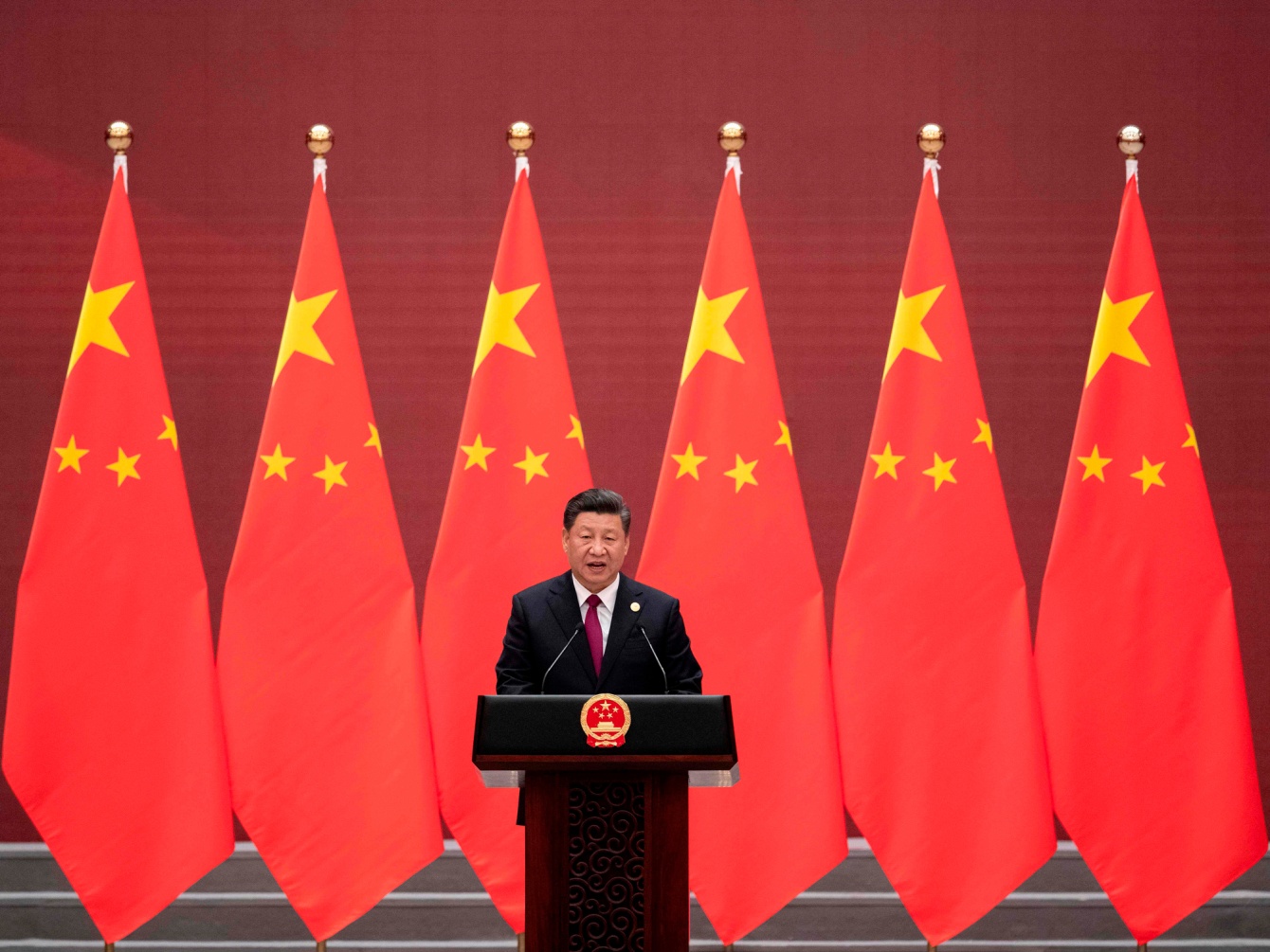

| China's top diplomat, Yang Jiechi, came to Alaska this week loaded for bear. Seated across from a new set of American foreign policy officials led by Secretary of State Antony Blinken, he unleashed a 16-minute jeremiad that signaled scornful indifference to U.S. complaints about China's domestic human rights abuses and international assertiveness in places like the South China Sea. "The challenges facing the U.S. in human rights are deep-seated," Yang said at one point, turning the tables by citing nationwide protests against the near-regular drumbeat of American police killings of unarmed citizens of color. Yang is a master of what's become known as "Wolf Warrior" diplomacy, a term that alludes to the Chinese Rambo-style action film, Wolf Warrior 2. And when it comes to the U.S., the Trump administration and the social upheaval of 2020 have given him plenty of ammunition. Although the stylized aggression of Chinese ambassadors and foreign ministry spokespersons has become a feature of President Xi Jinping's administration, it long predates him. We just haven't seen it practiced for a while. In the years before Xi ascended to power in 2013, China had experienced a period of "smile diplomacy." Now, no one's smiling anymore.  Yang Jiechi Photographer: Nelson Ching/Bloomberg This week in the New EconomyIndeed, as my Bloomberg colleague Peter Martin writes, Yang can turn on the charm when he wants to. The point to remember about Chinese diplomats, Martin explains, is that their words reflect the orientation of Chinese domestic policy. Yang went into "wolf warrior" mode in Alaska not to grandstand to a domestic Chinese audience—although his show of strength played well at home—but to align with Xi's no-compromise approach to the world. That's an ominous sign for U.S.-China relations. Martin is the author of a new book, "China's Civilian Army: The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy." I asked him what he made of the Alaska meeting in an email exchange. Andrew Browne: The talks in Alaska got off to a rough start. Does this clear the air or further poison the atmosphere? Peter Martin: The latter. A big part of the problem is that both sides want to return to a version of the past which is long gone. Beijing wants to return to an era when the U.S. moderated its political criticisms of China in exchange for cooperation on global issues like climate change and Iran. However, from detentions in Xinjiang to Xi's elimination of term limits, China has changed too much in the last four years to make that tenable for the U.S. Conversely, the Biden administration wants to conduct diplomacy with China as if Trump's "America first" policies never happened—a little like the guy who quits his job in a rage and then shows up for work the next day as if everything is fine. This irks Chinese leaders, and Yang was quick to point out this gap between U.S. rhetoric and practice. I think other Chinese diplomats are likely to follow his lead.  China President Xi Jinping Photographer: Nicolas Asfouri/AFP Browne: The Chinese side appeared to be looking tough for a home audience. Has this always been a feature of Chinese diplomacy? Martin: Chinese diplomats have always focused first and foremost on their home audience—even more than democratically elected foreign counterparts. Yang has always been particularly skillful at delivering the message Beijing wants to hear. Sometimes that's meant playing into the leadership's aims of charming the world and winning friends. At other times—and especially under Xi—it's meant acting tough and projecting confidence. Unfortunately that often results in dialogues where both sides end up talking past each other.  U.S. President Joe Biden (left) and U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken participate in a virtual meeting with leaders of Quadrilateral Security Dialogue countries March 12 at the White House. Photographer: Alex Wong/Getty Images North America Browne: Your book dives into the history of Chinese foreign policy. Is wolf warrior behavior a break from tradition or does it have precedents? Martin: China's had wolf warriors as long as the [People's Republic of China] has had diplomats. Time magazine described a speech one diplomat delivered at the United Nations in 1950 as a "two awful hours of rasping vituperation." In the 1960s, a Chinese diplomat wielded an axe outside the Chinese mission in London. In the aftermath of the Tiananmen crackdown, Chinese diplomats also came out swinging at their foreign counterparts before eventually pivoting to a softer approach. In general, the wolf warrior tendencies are most apparent at times of political tension in Beijing—when Chinese diplomats hope to shield themselves from charges of political disloyalty at home by acting tough abroad. Under Xi, we're seeing these same impulses play out, but they're combined with a powerful sense that China's time has come and that America's best days are behind it. It's this combination of insecurity and confidence that drives wolf warrior diplomats to act as they do.

Bloomberg New Economy Conversations with Andrew Browne: Big Pharma joined with governments to deliver coronavirus shots in record time. The successful moonshot could spur future research into other affordable drugs to treat global diseases. Join us March 23 at 10 a.m. ET when Katalin Karikó, senior vice president of Covid vaccine pioneer BioNTech, and others discuss Vaccine Miracles and the New Promise of Science. Register here.

__________________________________________________________ Like Turning Points? Subscribe to Bloomberg.com for unlimited access to trusted, data-driven journalism and gain expert analysis from exclusive subscriber-only newsletters. Get the latest on what's moving markets in Asia. Sign up to get the rundown of the five things people in markets are talking about each morning, Hong Kong time. Download the Bloomberg app: It's available for iOS and Android. Before it's here, it's on the Bloomberg Terminal. Find out more about how the Terminal delivers information and analysis that financial professionals can't find anywhere else. Learn more. |

Post a Comment