Timing a Reflating BubbleOne of the last things any investor should do is try to time a bubble. But when a bubble is upon you, you don't have much choice. Although there are always ways to hedge bets, you need some clear concept of the likely upside risk and sequence of events as speculation takes over. So, it appears necessary to take a look at the possibilities for bubble-timing. The latest minutes from the Federal Open Market Committee show that the governors of the Fed still see the risks surrounding inflation as weighted to the downside; they think a headline rate that's too low is more likely than one that's too high. Global markets are enthusiastically placing bets against this view. And the mere fact that the Fed's governors feel this way — largely because they rightly consider that the risks from the coronavirus are nowhere near over — helps to encourage investors betting on reflation. More cheap money for longer, a sensible approach if you are still worried about a recession and falling prices, helps to boost reflation if it arrives. It also oils the wheels of speculation. All history's great speculative bubbles needed cheap money, and there is enough around now to sustain another one. If reflation really does come through on cue, which is something to be wished for, the one major downside would be an increase in bubble risks. On that note, Wednesday's U.S. economic data, covering January, was quite a surprise. It was a difficult month, dominated by presidential politics and a sluggish start to the vaccination rollout. Yet producer price inflation boomed back. This is U.S. PPI, excluding food and energy:  The bad weather should ensure that broader inflation, including food and fuel, will be worse. Note that year-on-year comparisons still exclude last spring's collapse in the oil price. That is yet to show up in the figures. The data for retail sales were possibly even more surprising. Consumers remained largely inactive last month in the U.S.; but total sales were up strongly on the year before — a comparison that, again, doesn't yet capture the beginning of the pandemic shock:  It's fair to say that the risks of economic overheating have increased since the Fed met, then. What of market risks? Burrow through the Fed minutes, and you will find this worryingly sanguine passage: The staff provided an update on its assessments of the stability of the financial system and, on balance, characterized the financial vulnerabilities of the U.S. financial system as notable. The staff assessed asset valuation pressures as elevated. In particular, corporate bond spreads had declined to pre-pandemic levels, which were at the lower ends of their historical distributions. In addition, measures of the equity risk premium declined further, returning to pre-pandemic levels. Prices for industrial and multifamily properties continued to grow through 2020 at about the same pace as in the past several years, while prices of office buildings and retail establishments started to fall. The staff assessed vulnerabilities associated with household and business borrowing as notable, reflecting increased leverage and decreased incomes and revenues in 2020. Small businesses were hit particularly hard.

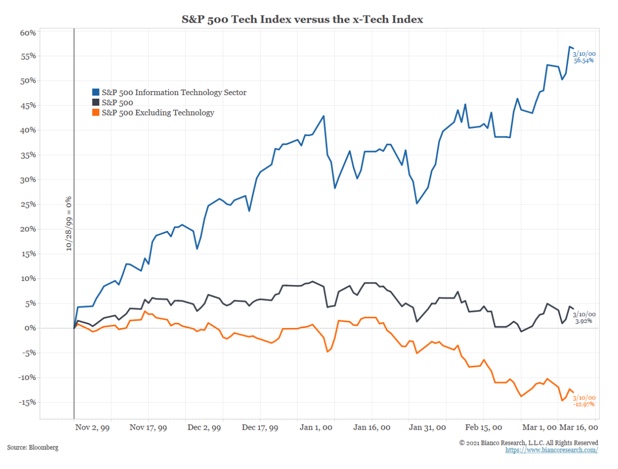

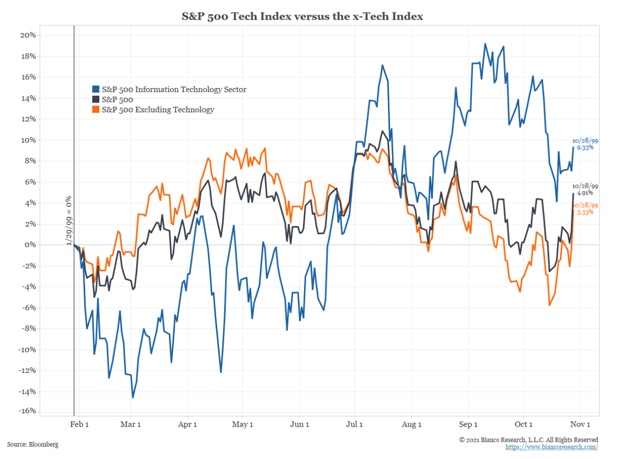

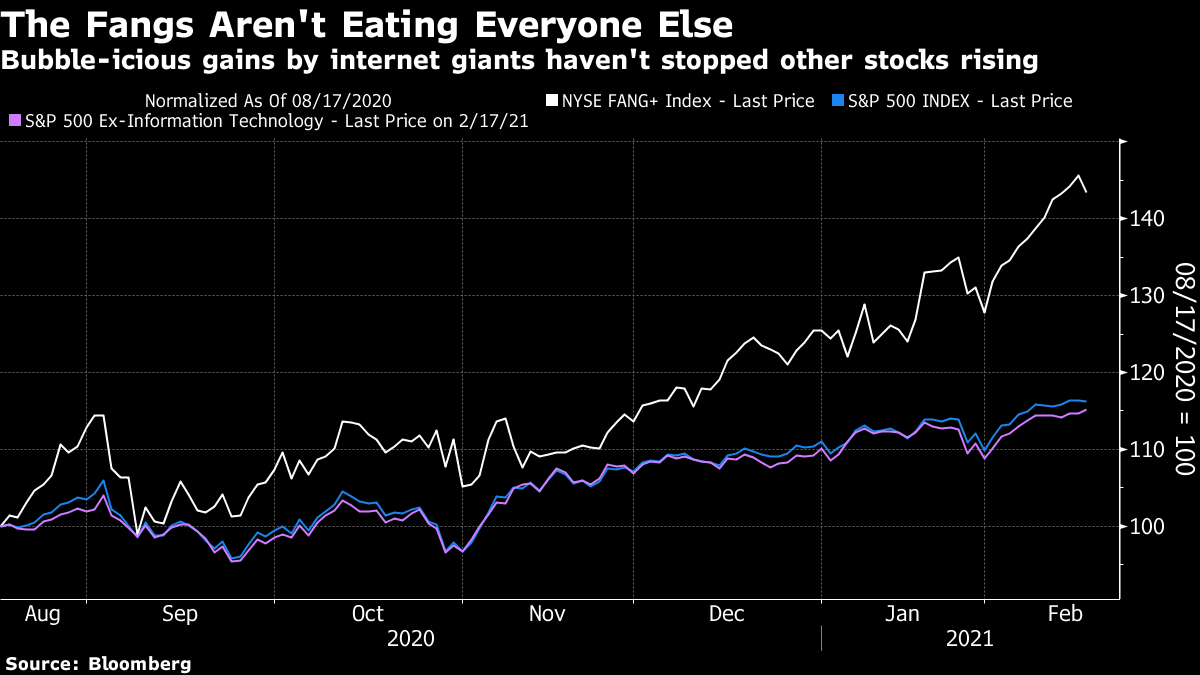

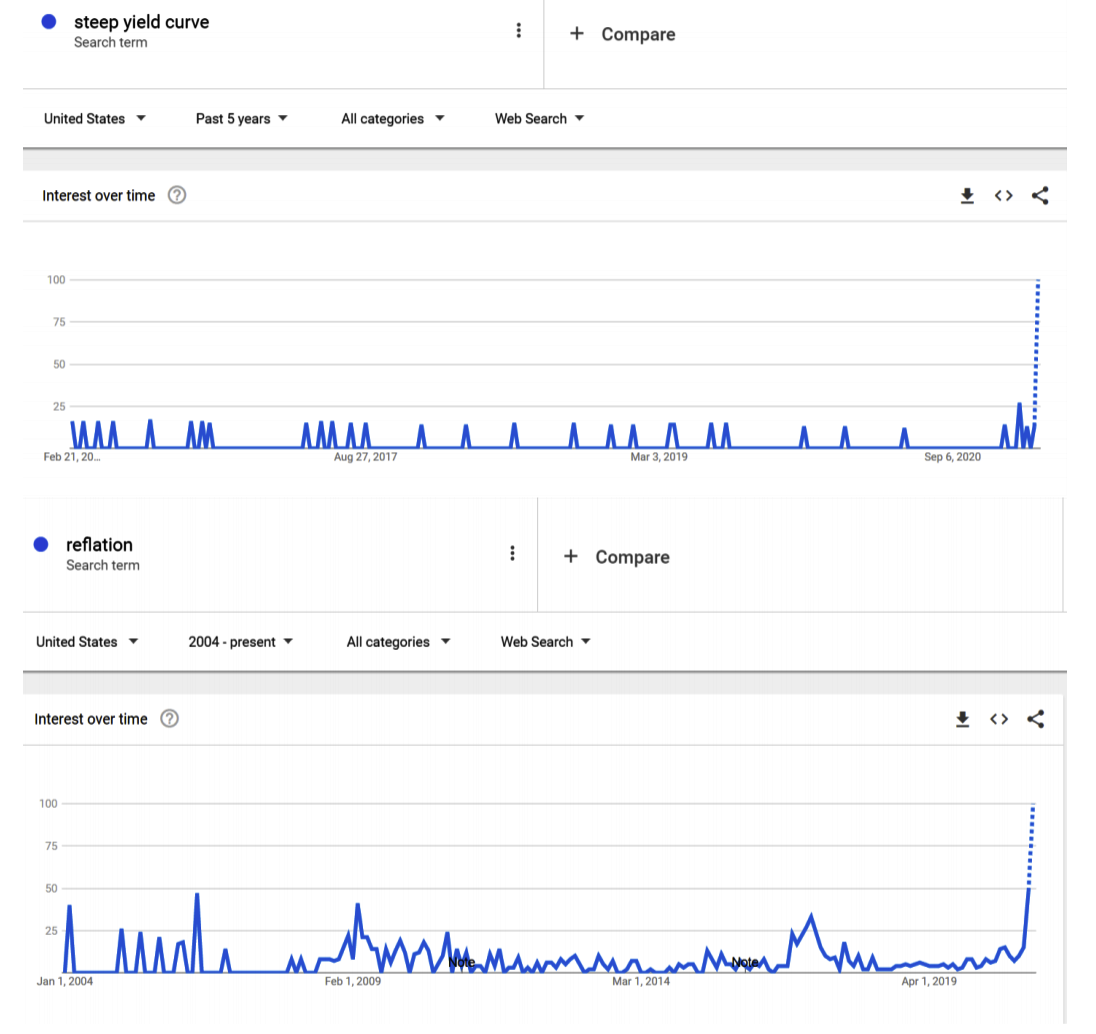

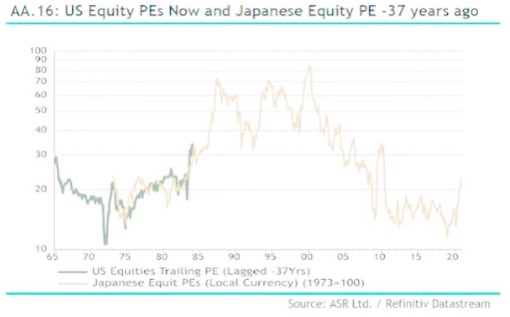

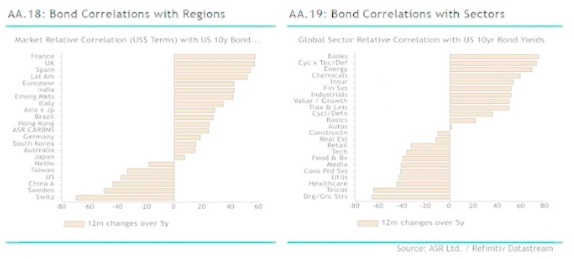

This was the meeting that took place with the GameStop Corp. excitement at its height, and Fed Chairman Jerome Powell ruled out putting tighter controls on margin debt. He has in the past cast doubt on the wisdom of central banks trying to identify or puncture asset bubbles. As far as he is concerned, timing bubbles is as bad an idea for central bankers as it is for investors. This is a reasonable position, but it leaves us with a central bank committed to easy money and worried about financial stability while unprepared to do anything about it; signs that reflationary pressure is stronger than we thought; and any number of examples of the "crazy" behavior that generally shows we are into the speculative final stage of a bubble. I won't recap them here. Can we somehow work out when the bubble is going to end? Just because we cannot know for certain doesn't absolve us from trying. Excluding acts of god (or mutating coronaviruses), the final manic or "Ponzi" stage of a bubble does have some distinguishing characteristics. We have few examples to choose from, and nothing can be shown with any statistical robustness; there just isn't enough data. But the last few doses of speculation give us some ideas. Bloomberg Opinion colleague Jim Bianco points out that in the final stage of the dot-com boom, the market narrowed sharply. While the tech sector shot for the moon, investors needed to bail out of other stocks to fund these investments. Over the last five months of that bubble, the S&P 500 excluding technology fell by more than 10% while tech gained more than 50%:  This was a change from the previous pattern. For much of 1999, possibly the maddest market year on record, tech stocks rallied without getting in the way of the rest of the market:  Now let's take a look at the last six months. I substituted the NYSE Fang+ index as the best modern exemplar of where the excitement is. The FANGs did have a little-remembered correction in early September. Since then, their rally has been mighty impressive once more — but it hasn't stopped the rest of the market registering decent gains:  This suggests we should maybe buckle up for a few more months before speculation reaches a peak. Then there is the issue of retail involvement. Traditionally, individual investors arrive at the end of a bubble and bear the brunt of the losses; they get to be the final "greatest fools" who buy at the highest price. Obviously, the GameStop excitement shows that retail money is getting involved in a big way, and having an impact. But there are more stimulus checks to come, and the evidence is that many retail investors are only now beginning to get interested in the possibilities of the "reflation trade." The following Google Trends charts were prepared by Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts, who suggests a final paroxysm of buying lies ahead:  Sudden interest in the arcana of reflation suggests that we should brace for retail money to test the Fed's resolve to keep policy easy. Moving on to valuation, we come up against the problem that an expensive market can always become even more expensive. For one terrifying example of this, consider the following chart from Absolute Strategy Research. Having been bearish on equities, Absolute Strategy threw in the towel last month and recommended moving overweight equities to balance a necessary move to be underweight in bonds. This also in part acknowledged the risk that a bubble is forming. The chart compares the price-earnings ratio of Japanese stocks in 1985, when the peak was several years away, with American P/Es now. There is an upside risk that stocks will for a while enjoy infeasibly high valuations:  More liquidity would only accentuate the arguments for a final splurge of speculation — and history suggests that the moment when the bubble peaks and bursts would be the moment when the cheap money is finally removed. How to deal with this? In these circumstances, bonds aren't a hedge. Those with money they can afford to lose might like to try to time the top. Get it right and you can retire a year or two earlier. Those with really strong constitutions could even try shorting the many low-quality small-caps that have been driven higher by the same wave of activity that gave us GameStop — although, to be clear, shorting anything in a bubble is very dangerous. The many of us with a longer time horizon than the next year or two can simply look through this next phase completely. That would mean putting very little money in FANG-type stocks, which may well hurt for a while, but it can't be helped. Professional money managers who will be judged by their short-term performance don't have these luxuries. The likelihood is they will lead the market toward a collection of assets that should do well in an environment of rising bond yields. For them, and for all of us, the following Absolute Strategy chart is useful. It lists regions and sectors by their correlation to rising bond yields:  Bank stocks, naturally, tend to move in the same direction as bond yields. Geographically, higher yields in the U.S. would strengthen the already popular argument for ploughing money into western Europe and emerging markets, and avoiding the U.S. And of course commodities and real assets in general make sense in an environment of rising inflation. This is a rather boring way of dealing with what is shaping up to become a very exciting chapter in market history. But it might be the most sensible way to do it. Assume there is a reflationary bubble coming, and position to have at least some long-term compensation if the possibility of inflation comes true. Survival TipsAs trading madness is back in the news, I'd like to suggest an entertaining read on the subject of sometimes bonkers speculation: Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, by Edwin Lefevre. It's a very readable and entertaining account of the adventures of speculator Jesse Livermore in the opening decades of the last century. Without Reddit groups to help him, or high-frequency traders, or even internet or electronic trading, he got into some remarkable high jinks, losing and making many fortunes. With the GameStop affair reaching the House of Representatives on Thursday, and charges now being made against the first Redditor to start recommending the stock, it's an ideal book to ask ourselves what is truly excessive, and what is natural in markets. And also, what is truly new? We will be discussing the book in a live blog on Wednesday, March 17, in the U.S. morning before the FOMC meeting that afternoon — a classic quiet time for markets, which you can put to good use by discussing this book with other people on the terminal. Please get reading. Finally, as I have just suggested commodities might be a good idea in time of reflation, let me quote this passage, as Livermore bemoans the fate of his attempt to corner the coffee market in the dying months of the First World War. With supplies constricted thanks to the many ships that had been sunk, "there wasn't any cleverness about it it; it was simply that I wasn't blind." Coming sure and fast, that profit of millions! But it never reached me. No; it wasn't side-tracked by a sudden change in conditions. The market did not experience an abrupt reversal of form. Coffee did not pour into the country. What happened? The unexpectable! What had never happened in anybody's experience; what I therefore had no reason to guard against. I added a new one to the long list of hazards of speculation that i must always keep before me. It was simply that the fellows who had sold me the coffee, the shorts, knew what was in store for them, and in their efforts to squirm out of the position into which they had sold themselves, devised a new way of welshing. They rushed to Washington for help, and got it.

There's nothing new under the sun. And I think you'll enjoy reading the book. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment