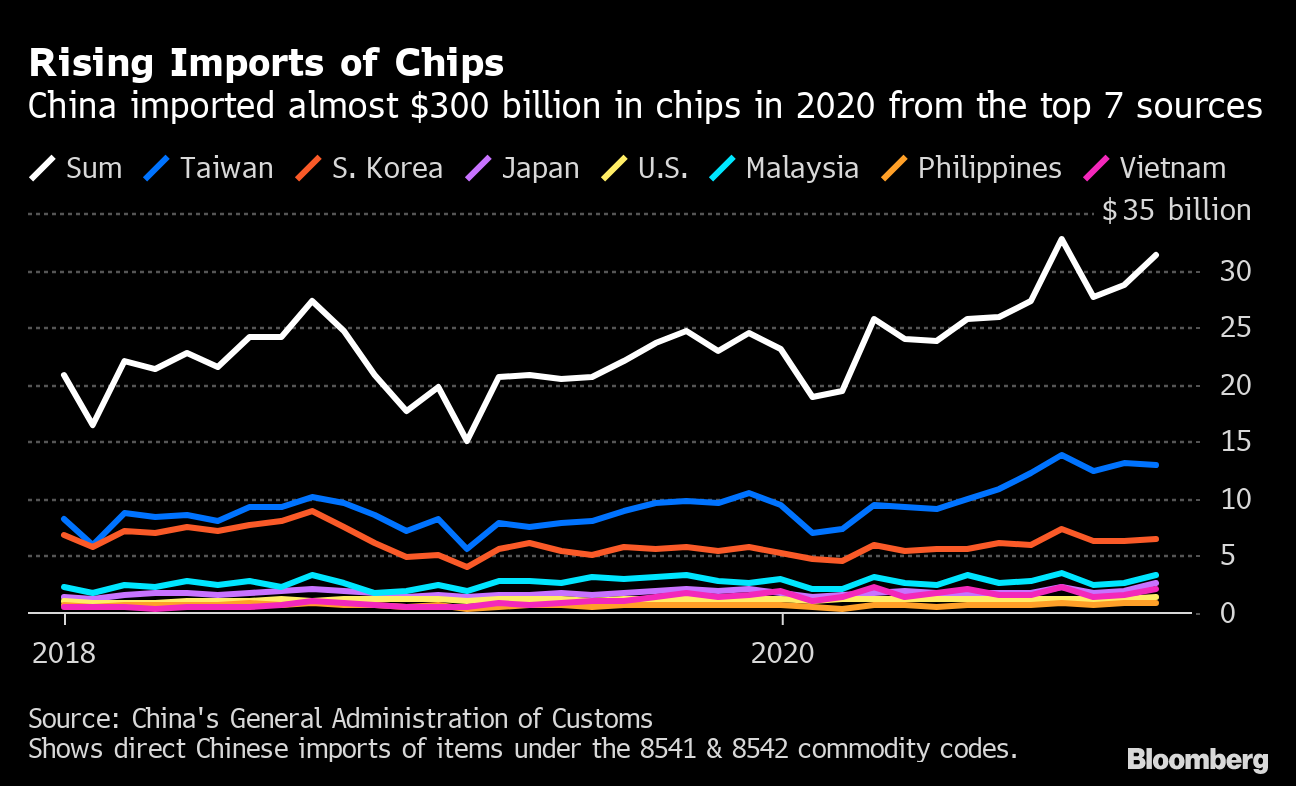

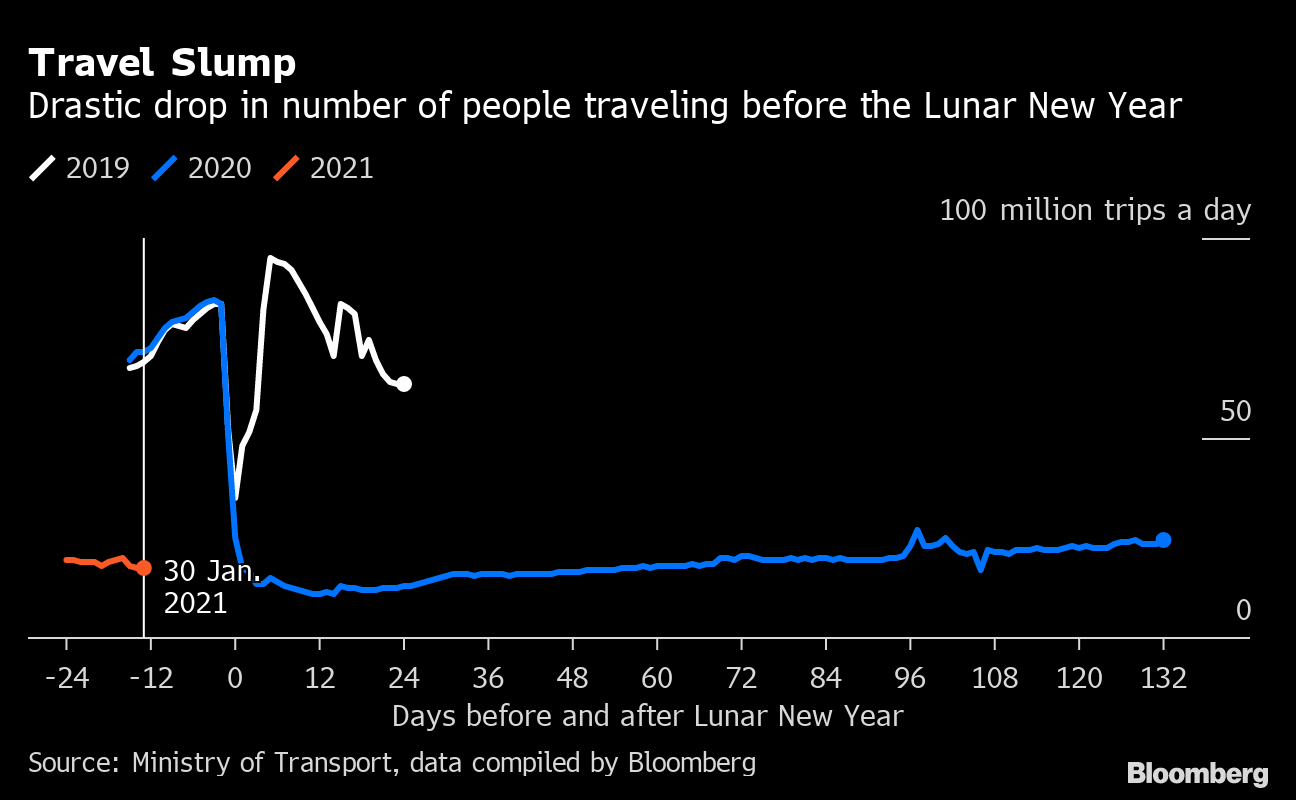

| Some degree of decoupling between the U.S. and China looks increasingly inevitable. It was revealed this week that U.S. President Joe Biden plans to order a government-wide review of critical supply chains. The goal is to reduce reliance on other countries for essential medical supplies and minerals. By doing so, Washington hopes to prevent future shortages and also limit the ability of foreign powers to exert leverage over American decision-making. These are motivations that will resonate in Beijing, even if the products in question are different. Instead of personal protective equipment and rare earths, China's concern is computer chips. Chinese imports of semiconductors surged by about 14% last year to almost $380 billion, accounting for 18% of all goods the country bought from overseas in 2020. The scale of these purchases underscores both the importance of chips to China's economy and the extent to which it relies on others.  It was the administration of former President Donald Trump, of course, that weaponized this reliance by cutting Chinese companies such as Huawei off from their American suppliers. It's hard to know if those sanctions were what led Beijing in late 2020 to make technology self-sufficiency a strategic priority, but it almost certainly provided momentum for the move. Indeed, China has not only been buying more chips, it has also substantially increased purchases of the equipment needed to make its own. Imports of such gear from Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and elsewhere jumped 20% last year to $32 billion. And it's a trend that looks set to continue, given Beijing's emphasis on self-sufficiency and the aversion in Washington for easing sanctions against Huawei. New Chinese regulations proposed last month that would give the government greater control over the production and export of rare earths will likewise heighten U.S. concerns. There's not much the U.S. and China see eye-to-eye on these days, but they do seem to agree on this: Each should need the other a little less. Dent to GrowthA resurgence in Covid cases in China, combined with worries that winter's colder weather will facilitate further infections, has prompted a number of local governments to impose restrictions aimed at curtailing the virus's spread. Those measures are already showing up in the form of weaker economic data. Gauges tracking the manufacturing and services industries all reported weaker-than-expected readings for January. And while the data indicate the economy is still growing, they also suggest that expansion is fragile. Nowhere was that brittleness more obvious than in transportation. The period ahead of the Lunar New Year — which starts on Feb. 12 this year — is usually a peak season for travel as millions return to their hometowns for family reunions. This year, however, authorities are encouraging people to stay home, and it appears many are listening. The number of travelers has plunged compared with the past two years. That augurs poorly for holiday spending.  U.K. and China ClashChina's ties with the U.K. have been fraught as of late. Among the issues the two sides have clashed over are Britain's decision to ban Huawei, the imposition of Hong Kong's national security law and the treatment of ethnic minorities in the province of Xinjiang. That's why it was noteworthy this week when Premier Li Keqiang took time to address a conference hosted by Chinese and British business groups. The speech Li delivered was a reassuring one. Not only did he say that Beijing hoped to put relations on a "firmer footing" but added that China's commitment to its ties with the U.K. was as strong as ever. But as if on cue to highlight how difficult it will be to stabilize the relationship, Britain's media regulator announced a day later it was pulling Chinese state-owned television channel CTGN off the air. Regulating AntThe question that's captivated much of China's financial community since authorities halted Ant Group's massive IPO in November has been how Beijing will regulate Jack Ma's sprawling fintech giant. There appeared to be at least a partial answer this week: very much like a bank. That's because Ant and regulators agreed that the company, inclusive of all its businesses, will be turned into a financial holding company. While numerous details remain unknown, this transformation will almost certainly force the company to slow the torrid pace of expansion that had made it one of the world's most-valuable startups. But there's also an optimistic way to see that development. Any progress toward a resolution of Beijing's concerns also moves Ant a few steps closer to potentially resuming its IPO. Financial markets, at least, seemed to take the glass-half-full view this week. That was evident when affiliate Alibaba Group began selling $5 billion of bonds and promptly drew as much as $38 billion of orders. There are many reasons for why investors would be so enthusiastic, though it's hard to imagine this level of gusto if there were genuine worries about a breakup of Jack Ma's empire.  An employee walks through the campus of the Ant Group Co. headquarters in Hangzhou, China, on Jan. 20, 2021. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg What We're ReadingA few other things that caught our attention: And a programming note: There won't be a Next China newsletter for the next two weeks because of the Lunar New Year holidays. We'll be back with a new edition on Feb. 26. |

Post a Comment