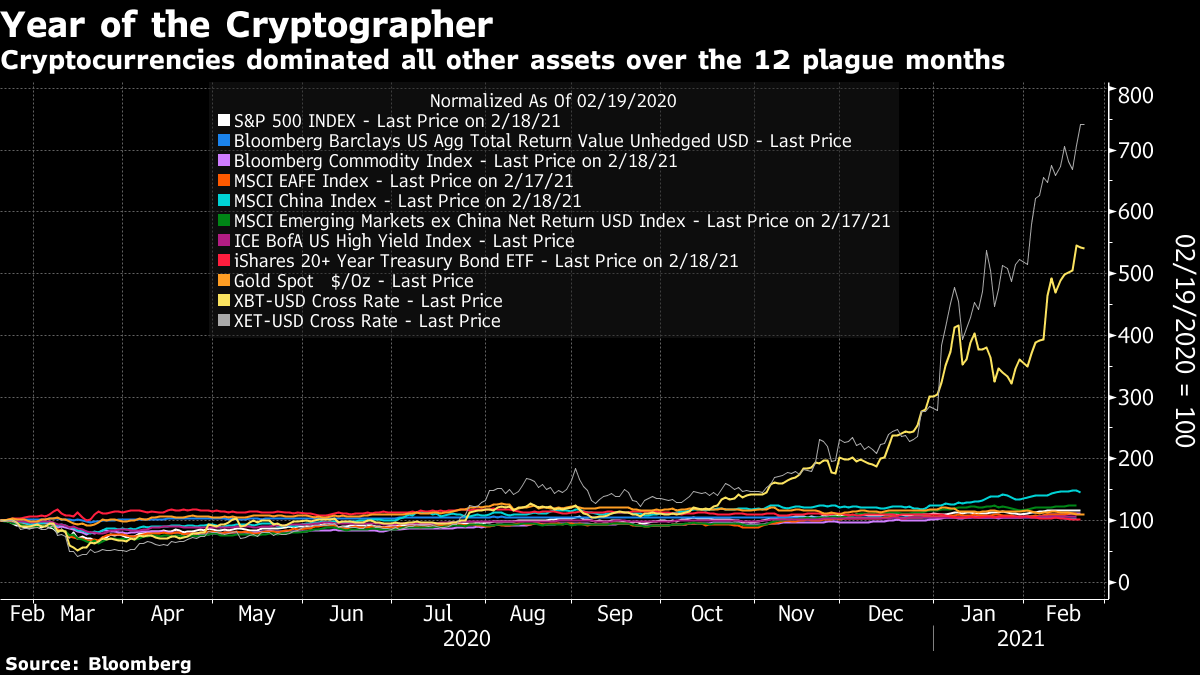

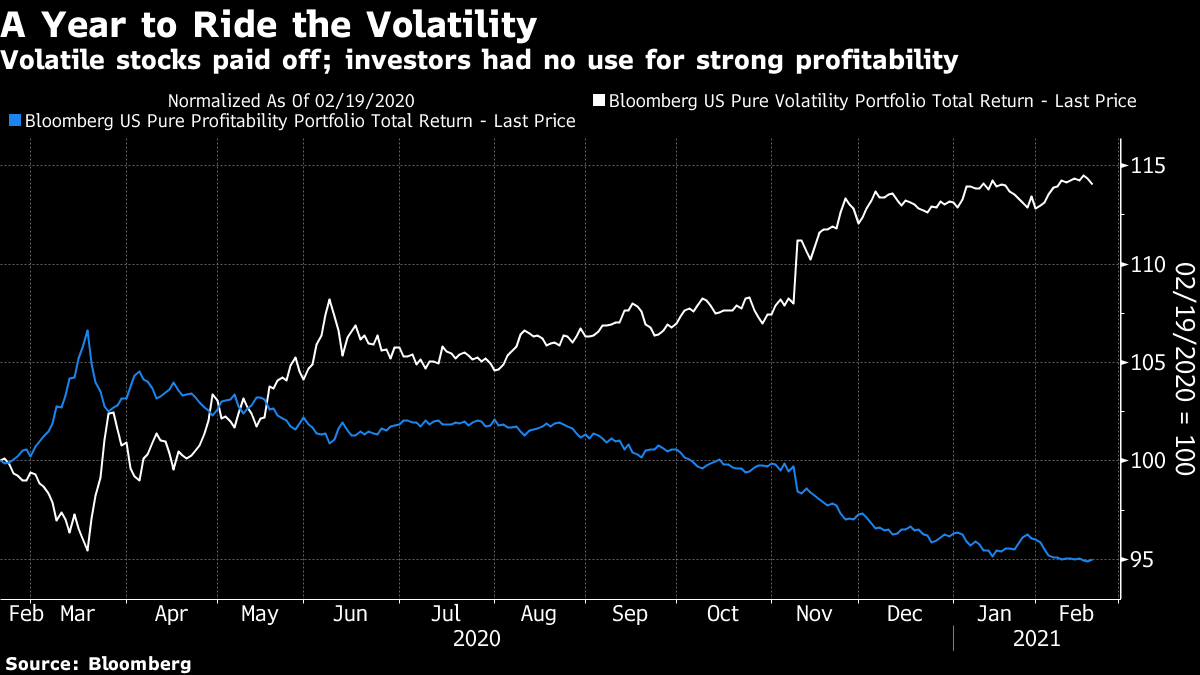

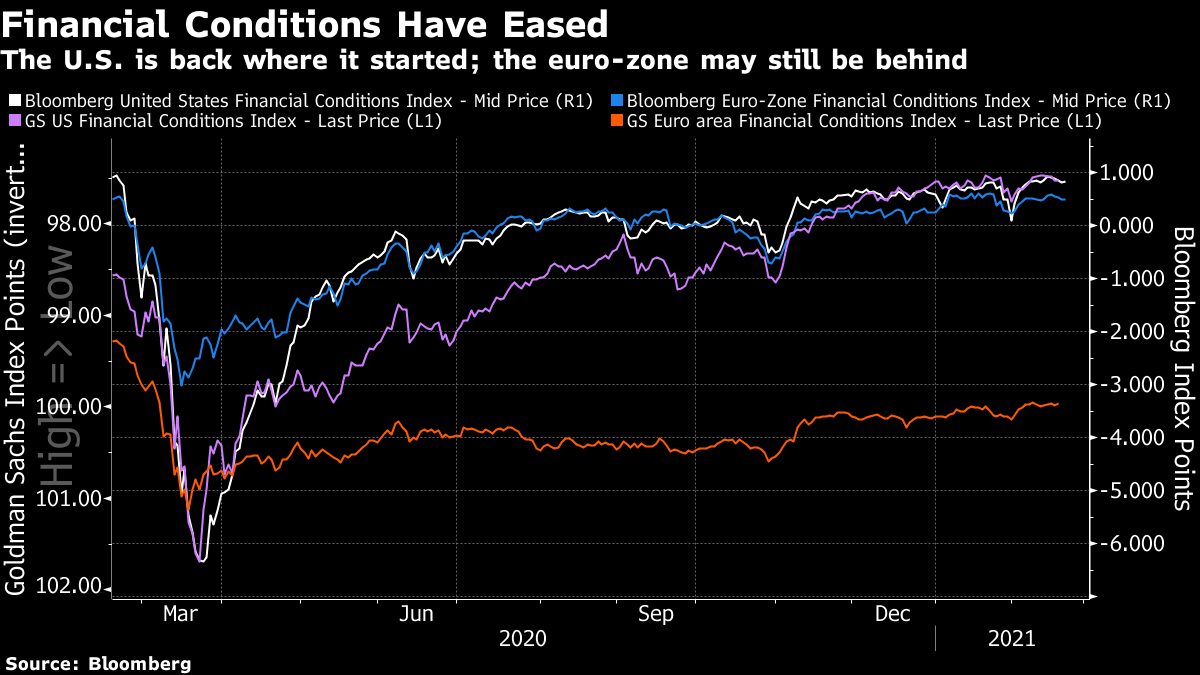

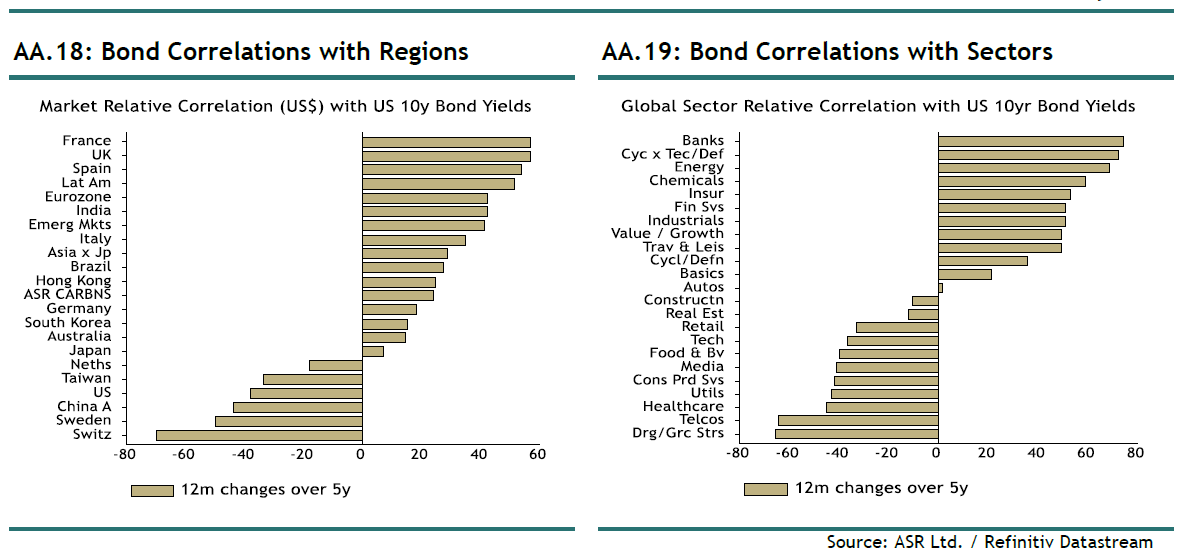

A Market Diary of the Plague YearHappy anniversary, everyone. As far as markets are concerned, it is exactly one year since the modern plague of Covid-19 hit. It was on Feb. 19 that stock markets peaked, and then began a slide that turned into a rout as it grew clear that the novel coronavirus starting in the Chinese city of Wuhan had made landfall in the developed countries of the West. At that point, nobody had died of the disease in the U.S. The lockdowns that would soon spread from Italy across western Europe and the Atlantic remained a few weeks in the future. But it was at this point that the coronavirus asserted itself over global finance and markets. I cannot see how anyone could have predicted exactly what would happen over the next 12 months. To do so would have taken an advanced understanding of epidemiology, an awareness of advances in vaccine technology, and an ability to read the minds of both central bankers and (unlike in the last few financial crises) treasury ministers. But remarkably, it turns out that anyone with a moderately sensible diversified portfolio would have been fine. And those with a taste for risk and a lot of luck could have made themselves rich. Here is my attempt to tell the tale of the plague year, as experienced in financial markets, armed only with a Bloomberg terminal. The most basic fact to master is that all the main asset classes are higher now than 12 months ago. Only spectacularly bad security selection could have inflicted a loss. Over the full year, Chinese equities have romped away with the strongest returns, followed by the rest of the emerging markets. But all the main categories of debt, and the main commodity indexes, are also showing a profit:  Anyone wanting to do some fancy tactical asset allocation would have loaded up on long bonds just before the U.S. Treasury yield dropped below the unimaginable level of 1%, switched to gold for a few months subsequently, and then piled into Chinese equities. But that would have been gilding the lily. Meanwhile, what has happened in the world of cryptocurrencies in the last few months is of a completely different order of magnitude. It looks like a sign of speculative excess, or even desperation, but it is affecting the financial landscape. Here is the same chart, with lines added for the most widely held cryptocurrencies, bitcoin and ethereum:  How much did Covid-19 have to do with all of this excitement? My favorite way to isolate the precise effects of the pandemic has been a "Covid Fear" gauge showing the relative performance of sub-indexes for U.S. food retailers and for hotels, resorts and cruise lines. The former should expect to do well from extreme lockdowns, while the latter should do terribly. Over the last 12 months, that gives us the following read-out:  Initial all-out terror gave way to relative calm as the first wave passed, although anxiety remained elevated through the summer as the U.S. Sun Belt states suffered a surge of infections, followed by a second wave in western Europe. The announcement of successful vaccine tests by Pfizer Inc. on Nov. 9 was a big development in reducing fear; the arrival of new variants in the U.K. and then South Africa, and some well-publicized problems with the vaccine rollout, particularly in continental Europe, revived anxieties after that. As it stands, anyone who bought food retailers while shorting hotels 12 months ago is still sitting on a handsome profit, but fear is much more contained than it was. Beyond Covid-19, there was something of a watershed moment in early September, when booming tech companies suffered a sharp correction. These mega-caps, which dominated for the first half of the plague year, have since underperformed relative to small-caps, which have done fantastically. New retail money drove much of this; it is almost as though fresh risk appetite was injected with the vaccine.  However, there was no such clear watershed when it came to the contrast between the value and growth styles of investing. Growth is generally held to do better when it is feared to be in short supply — so it is a little disconcerting, to say the least, that value has made such a weak recovery. Again, it is possible that new retail money has something to do with this; new investors seem interested in low-quality companies with bad balance sheets, which value investors find it hard to touch.  Digging deeper into the factors that drive equity performance with Bloomberg's FTW (factors to watch) function, tends to underline that the market has been driven by an unusual version of risk appetite since Vaccine Monday in November. If not "irrational exuberance," it certainly appears to be something like "irresponsible exuberance." Or, less kindly, "stupidity." A number of stocks have done well thanks to cases of mistaken identity over the last year. Investors piled into a company with the ticker symbol "ZOOM" that had nothing to do with the video-conferencing app early in the plague year; more recently, they plunged into Signal Advance Inc. after Elon Musk recommended switching to Signal, an unrelated messaging app. It is alarming that such stupidity can move share prices. Meanwhile, the single worst-performing factor of the last 12 months for U.S. stocks of all capitalizations has been profitability, according to the wonks at Bloomberg. Holding all else equal, companies that do a really good job of squeezing out earnings have been punished for it. The best factor has been volatility; all else equal, the more a stock's price tends to swing around, the better it has done, particularly since Vaccine Day. When large numbers of people truly believe that "stocks only go up," perhaps this is inevitable. It may not be pretty when they discover that volatile stocks also go down.  Naturally, pandemic news cannot explain everything. This has been a worse year for developed economies than virtually anyone would have had as their base case 12 months ago, and there are still plenty of questions over how long the economic disruption will persist. The response of vaccinologists was plainly important to markets; central bankers, as ever, were even more so. Both Bloomberg and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. produce indexes of broad financial conditions, incorporating measures from a number of different markets, for the U.S. and for Europe. Combining them on the following chart, we see virtually total agreement that after a terrible shock last March, U.S. financial conditions are back to normal. Our methodology produces different outcomes for Europe, with Goldman's measure suggesting that the continent's financial conditions have improved far less. But plainly they have grown much easier since March.  Looking at credit spreads, the results are remarkable. Last March, the fear was that illiquidity would inflict a crash on the world. After that, concern persisted of a solvency event, as businesses and landlords who had lost revenue due to the pandemic eventually gave up and defaulted. Those fears are over. Emerging market spreads are almost back to where they were 12 months ago, while within the U.S., high-yield bonds actually trade on tighter spreads than they did last February. They have done this despite plenty of new issuance.  Government action has certainly had quite an effect in dampening solvency concerns, and making it easier for companies to raise funding once more. Could this lead to an even more debased and sluggish version of capitalism, in which otherwise unprofitable companies are able to limp on thanks to cheap debt, and deny capital to those that might use it better? Plainly, that is the risk. Buying a way out of this financial crisis may turn out to be at the cost of further economic malaise in the future. But as it stands, the debt of riskier companies is held to be safer now than it was 12 months ago. Finally, the single most important event of the last 12 months, as far as markets are concerned, is the explosion in the supply of money. The following chart shows annual percentage changes in the level of U.S. M2, a broad measure of the money supply, over the last 20 years. It is common to draw parallels with the response to the global financial crisis of 2008, when central banks also resorted to printing money. That would be a mistake. The monetary shock administered about 11 months ago is off the charts compared to what happened in the aftermath of the last crisis. Many complained that the fiscal and monetary response to the GFC was too slow, leading to the sluggish decade that followed. Central banks certainly haven't repeated the mistake. Whether they have made a different one is a question that will be answered long after the plague year:  Where does this leave us? The last 12 months will go down in financial history, and will be explored for decades to come. Things might have been very different but for the happenstance that plans for a vaccine against a disease very similar to Covid were already almost ready to go when the year dawned; for a fascinating take on this, see this long read from Lawrence Wright in the New Yorker last month. A different financial response would also have changed history. As it was, it turns out that anyone who stuck to the established and dull investment virtues of patience and diversification would have done fine. And as the year went on, without jumping into the maelstrom of cryptocurrencies, it was possible to benefit from an intuition that the world was going to be alright by the classic means of investing in riskier assets that benefit from reflation, such as emerging market stocks, and commodities. Markets also seem to think that China is the global winner from the plague year. That's another hypothesis that will be tested in due course. For now, the first order of business is to handle the vaccine rollout well enough to validate all the hopes priced into the market. ClarityAn apology: A chart in yesterday's newsletter from Absolute Strategy Research was too indistinct for many to read. Here it is again, this time I hope in much clearer form:  To recap the basic idea, the chart ranks geographies and sectors according to their correlation with higher bond yields. The countries and sectors at the top will do well out of higher bond yields; the ones at the bottom will do worse. So if you think bond yields are going to keep rising, European banks look like an interesting bet, all else equal. If you think we are due another dose of deflationary dread, consider taking refuge in Switzerland. Survival TipsEvery day I learn more about the Points of Return readership. It turns out that there are a lot of romantic comedy aficionados out there. So here are some more romcoms that I missed earlier this week: Mr Right Austenland The Wedding Planner The Proposal Always be my Maybe Crazy Rich Asians And for the classically inclined: It Happened One Night The Thin Man Series His Girl Friday There's also a vote for: The Holiday Nobody has taken issue with my contention that When Harry Met Sally is the greatest of all romcoms. See it if you haven't; it might just transform another miserable night in. Here's my favorite song from the soundtrack: It Had to Be You, as sung by Frank Sinatra. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment