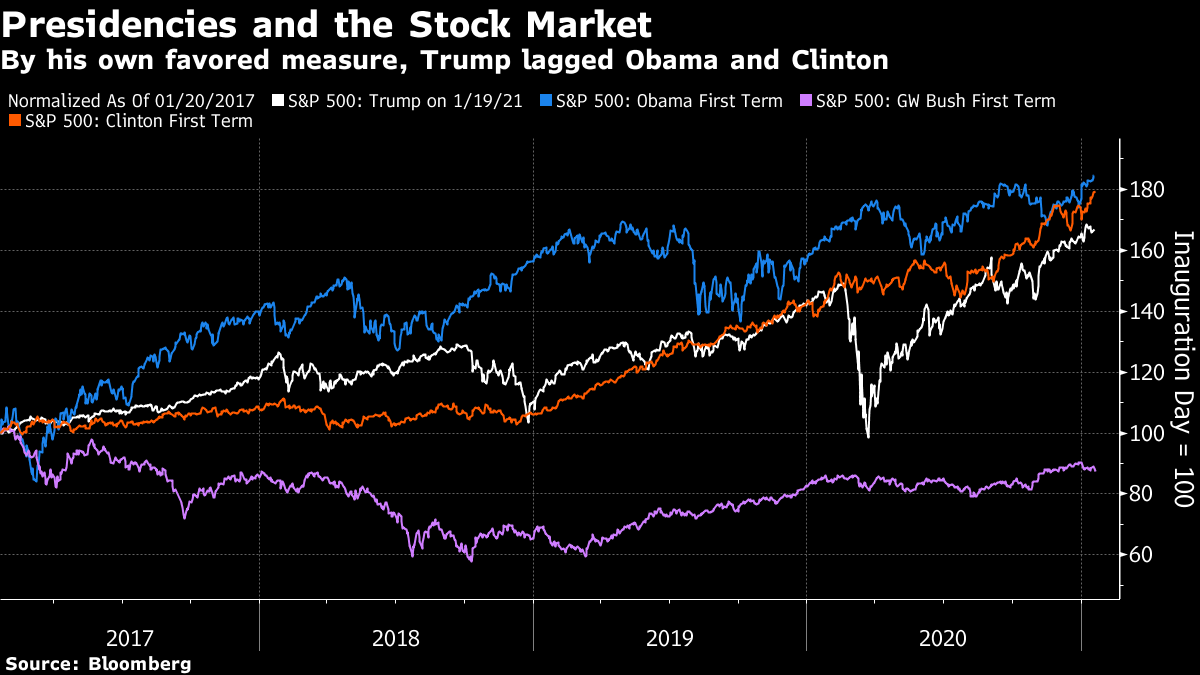

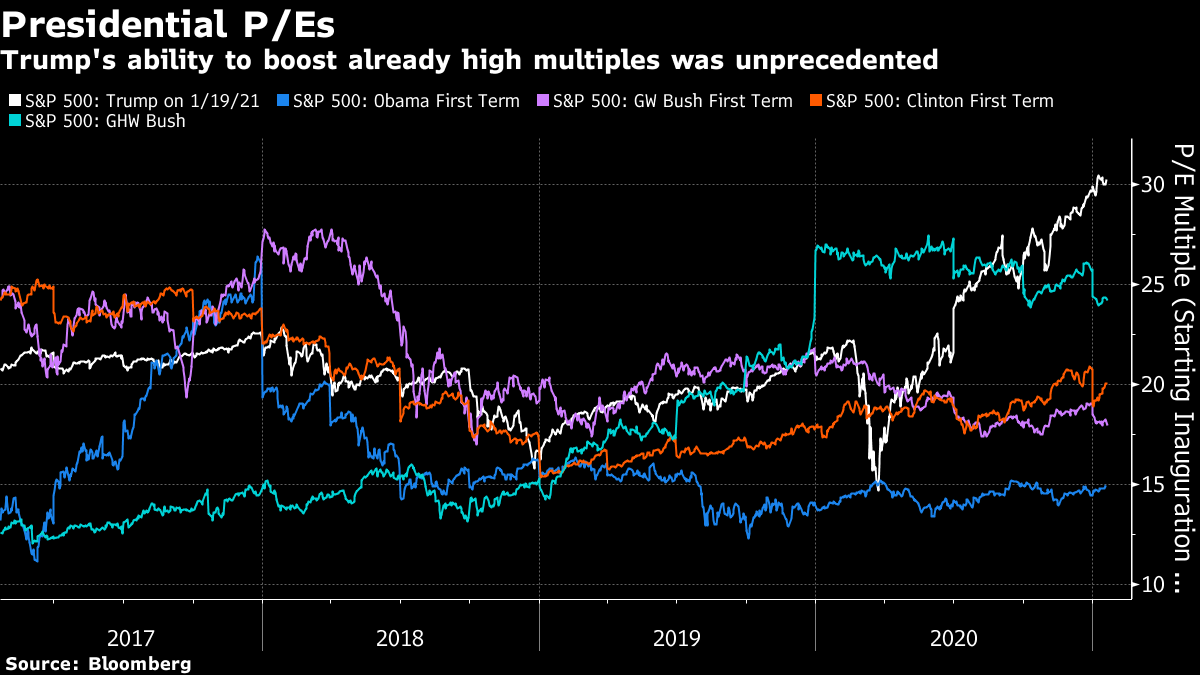

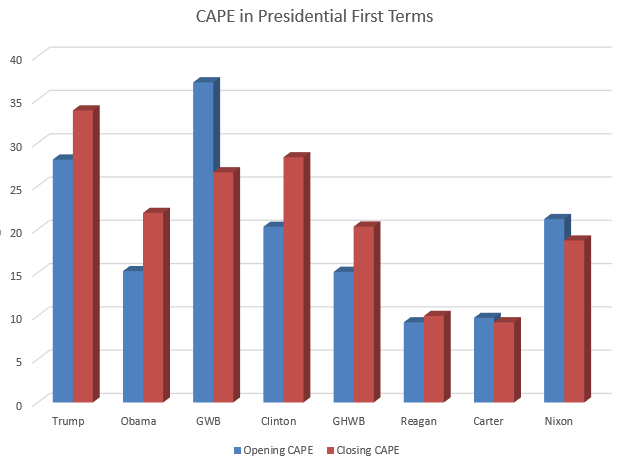

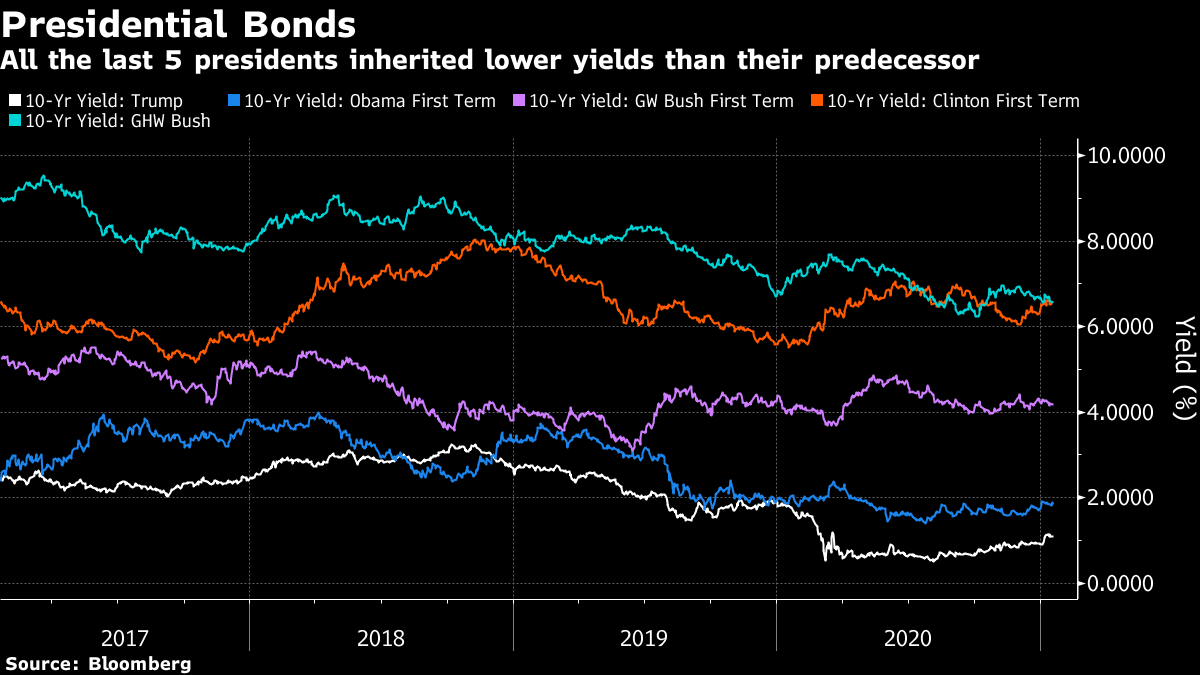

Markets Aren't the MeasureWe don't yet know how history will judge Donald Trump's presidency, but we know how he wanted his term in office to be evaluated — by the performance of the stock market. From the earliest days after his election, he keenly tweeted the market's strong reaction to his victory, and he continued to hype the succession of records on his watch. This was always somewhat of a dumb idea. But as this is what he wanted, here is how the Trump presidency compared with the first terms of his three predecessors, Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton. In all cases, the performance of the S&P 500 has been normalized to start at 100 on their inauguration days:  Trump's term in the end lagged behind both Obama and Clinton. Before the pandemic implosion 11 months ago, he was at least keeping pace with Clinton, and the rebound since last March has been extraordinary. And of course the Trump market has fared far better than the George W. Bush version. Is this a fair way to judge the Trump presidency? Of course not. To start off, what matters most for stock market returns is the price at which you buy. The cheaper the entry point, the greater the chance that prices will rise. Obama took office with the market approaching the trough after an epic collapse, and George W. Bush arrived just as a historic bubble had started to burst. Looking at moves in trailing price-earnings multiples over the first terms of the last five presidents, the incumbent who oversaw the greatest increase was George H. W. Bush, who inherited a market still reeling after the Black Monday crash, and left with confidence returning. Trump stands out as the only president to inherit an already expensive stock market and leave with multiples even higher. No other first-term president has overseen a market where investors were so optimistic (although Clinton did so in his second term):  Does this suggest that Trump has done something special? Probably not. Trailing P/E multiples adjust to the perceived point in the business cycle. In the case of the first President Bush, stocks were priced on the assumption that the cycle was nearing its top when he arrived, and around its bottom when he left, with the result that the multiple may have risen a lot without indicating any true growth in confidence about the future. So, now let us compare cyclically adjusted price-earnings multiples, in which prices are compared to average inflation-adjusted earnings over the previous 10 years. This adjusts for the tendency of P/Es to move according to the economic cycle. Using data from the website of Robert Shiller of Yale University, these are the opening and closing multiples for the first terms of the last eight elected presidents, going back to Nixon:  On this basis, several other presidents managed to boost multiples by more during their first term. But nobody has ever inherited a market as richly valued as it was in January 2017 and left it even more expensive four years later. One of the main reasons for thinking that Trump was unwise to judge himself in this way was that he was bequeathed such a market. Amazingly, despite that handicap, the S&P performed not so much worse under his watch than it did under Obama and Clinton. But now we need to dig further. Trump had the handicap of inheriting high earnings multiples, but he also had the benefit of low interest rates. Ten-year yields, shown below, were slightly lower on his inauguration day than on Obama's and remained lower than at the equivalent point in Obama's first term for all bar a few weeks in late 2018 (which not coincidentally overlapped with a nasty sell-off in stocks). Every president since Reagan has inherited lower yields than his predecessor:  Such rock-bottom rates help to raise share multiples, all else equal. They also aren't necessarily something for presidents to be proud about. Lower yields imply that investors are confident in the government's ability to pay, but also that they don't expect the economy to grow much. In practice, if the incredibly low yields of the Trump years can be attributed to anyone, it is to the Federal Reserve, which sets monetary policy. Trump did appoint a new Fed chair, but his pick, Jerome Powell, was already on the Federal Open Market Committee and didn't represent a decisive break. More to the point, Trump ran for office as a monetary hawk, opposed to the Fed policies that have buoyed the stock market under his presidency. Speaking to Fox Business in August 2016, he said this: "Interest rates are artificially low. If interest rates ever seek a natural level, which obviously they would be much higher than they are right now -- you have some very scary scenarios out there. The only reason the stock market is where it is, is because you get free money."

If candidate Trump believed that to be true in August 2016, it would be interesting to hear why he doesn't believe it to be true now. All of this has been an exercise in trying to take seriously the notion that a strong stock market redounds to a president's credit. That strength is offered as a reason to support the president. In fact, given the market he inherited, it wouldn't have reflected badly on Trump if it had done far worse, or even fallen over the last four years. Beyond that, the president only has indirect levers for influencing the stock market, which will on occasions rise or fall for reasons beyond the president's control. The Covid pandemic and, years earlier, Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait, both caused brief but scary bear markets. Neither Trump nor President George H. W. Bush deserved much blame for these events. Are there any lessons for investors, or for Joe Biden? The most important is to resist any temptation to judge himself by the stock market. Biden inherits a market almost as expensive as the one that greeted George W. Bush. He should instead try to target something over which he might have a measure of control; in the short term, that means making sure the U.S. gets the logistics of the vaccine correct. Investors should look at how unusual the current circumstances are, and how little the presidents of the last 40 years have truly affected the stock market. It's best to try to factor out politics, even in the charged atmosphere of the present. The most important contribution President Biden is going to make, quite possibly in his entire four-year term, is the vaccine rollout. It's scarcely an ideological issue. If he gets it right, he will have plenty more political capital, and the reflation trade can get going with a vengeance. If he doesn't, the prospects are hard to contemplate. Old friend Janet Yellen, chairwoman of the Federal Reserve for four years, reintroduced herself in Senate confirmation hearings with a strong and clear statement of intent. What was most remarkable about it, in context, was the lack of a market reaction. The two key passages concerned fiscal policy and the dollar. On fiscal policy she was about as expansionist as she could have been: "The world has changed. In a very low interest-rate environment like we're in, what we're seeing is that even though the amount of debt relative to the economy has gone up, the interest burden hasn't….Right now, with interest rates at historic lows, the smartest thing we can do is act big.

And on the dollar, she tied herself to the mast of non-intervention. "The value of the U.S. dollar and other currencies should be determined by markets. Markets adjust to reflect variations in economic performance and generally facilitate adjustments in the global economy."

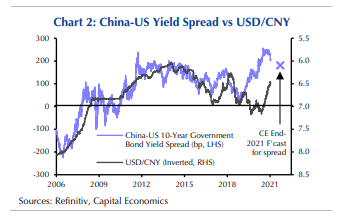

This gets her out of the trap of having to defend a stronger dollar, and it was taken on the markets as suggesting that the Treasury would happily allow the currency to weaken, even though Yellen said that this was not an objective. If that does happen, then there is a strong consensus that the dollar will weaken against the Chinese yuan — a move that will also have the handy side-effect of dousing down trade tensions. The current divergence between Chinese and U.S. yields implies significant further weakening for the dollar, as this chart from Capital Economics shows:  But it was interesting that neither currency nor bond markets reacted strongly to the comments, even though on their face they suggest a radical change of direction for U.S. fiscal policy. The reflation trade is well baked in, aided by the vaccine. Since Nov. 9, the day Pfizer Inc. announced the successful results of its vaccine trial, the dollar has depreciated against all the currencies represented in developed and emerging market indexes, with the sole exception of the Peruvian nuevo sol.  A steadily declining dollar makes life easier for many people, all over the world. Yellen is wise not to get in the way. Now to find out whether the overwhelming market consensus in favor of reflation and a weaker dollar is correct… Survival TipsWe are in the presence of an epic breakdown in trust. I wrote about this back in 2018, and the problem gets ever deeper. The presidential inauguration, 12 hours away as I write, is likely to be the clearest demonstration yet of the chasm that has opened up. Backing away from the specifics of Donald Trump and his claims of electoral fraud, there are two broad components to the polarization. The first is that many don't trust the most basic information given to them. Evidence to disprove a point of view can be dismissed as fake, and clear arguments against can be chalked up to bias. The second is a loss of mutual respect. People on both sides of the divide feel disrespected by those on the other. Put these together and you get the "echo chamber" effect, in which people listen only to sources that will reinforce their pre-existing positions. There are any number of reasons for this. The growth of inequality in the West has much to do with it. So does social media, which democratized news — reducing the hold of established news organizations — but also enabled the spread of disinformation. For some bone-chilling but fascinating examples of how these effects work, I suggest two podcasts produced by pillars of the liberal "echo chamber" that are devoted to talking to Trump supporters about their view of events. Try this one from the New York Times and this one from The New Yorker. What to do about it? That is the challenge for us all. If I have one suggestion, or survival tip, it comes from Joe Biden, who now will bear the brunt of trying to restore trust in society: We've got to change the nature of the way we deal with one another. And it starts off by the way your father was… and others. You don't question other men and women's motives. You can question their judgment, but not their motive.

Biden has a serious point. I get more negative feedback than I used to. The key change in the last few years is that it almost invariably starts by attacking my motives, rather than by critiquing my words. Many of the motives ascribed to me leave me gasping. It is important that journalists be accountable to readers, particularly critics. Holding a civil conversation with people who think you're wrong is never easy. But civil dialogue with those who are sure they can read your mind and start by impugning your motives is close to impossible. Let's treat people with respect, and argue about their ideas, not about their motives. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment