| Welcome to The Weekly Fix, the newsletter that is busy hunting down the person who invented Dry January. --Emily Barrett, Asia FX/rates editor. Where to start? It can only be with the turmoil on Capitol Hill. The scenes in Washington, D.C., left financial markets unscathed. That may be a testament to the continued faith in the power of America's institutions to absorb and resolve conflict, to protect democracy and the rule of law. That faith has long underpinned U.S. economic and financial success, and it's hard to think of a time when it has been more tested. President Donald Trump's incitement of an angry crowd, and the mobs vandalizing the Capitol, were assaults on those democratic pillars that may have longer-term consequences. U.S. politics "increasingly resemble that of an emerging market, where weak political institutions and polarized societies increase the risk of instability around elections," wrote Mark Rosenberg, of political-risk analysis firm GeoQuant. But he added that, economically, the nation remains "the most developed of the world's developed markets." Meanwhile, as the president has sought to sow dysfunction and cling to power, the pandemic rages on. It's now killed more than 361,000 people in the U.S. and threatens the livelihoods of millions. So... GeorgiaIf this newsletter sees another client note entitled "Georgia on my mind" it will shred itself. We have a result, thankfully, so such measures are uncalled for. And what a result. It's counter to all but the most contrarian forecasts following the U.S. election. And the U.S. 10-year yield, a benchmark for global borrowing, has surged ... well, above 1%.  The initial move wasn't exactly met with rapture among yield hungry investors. Japan's monolithic buyers barely suppressed a yawn, according to our reporter Chikako Mogi. (This is the week that Australia briefly outshone Italy with the most-attractive hedged sovereign yields in major developed markets -- see our Stephen Spratt's chart below.)  Of course, the global benchmark may find fresh impetus. Because if rates were easy to predict, there'd be no newsletters. Wall Street veteran Byron Wien sees it getting to 2% this year. And Nomura's experts reckon turbo-charged quant funds could sweep it higher from 1.10%. But the macro case for sharply higher yields risks straying into a couple of the bond market's hotly disputed territories. The first: Supply will push yields higher. The calls for higher yields are premised on more-generous government spending under a united Democratic Congress, which implies more debt issuance. As we've seen over the past decade, however -- and especially since March -- more issuance doesn't equate to higher interest rates. HSBC's Steven Major reminded us this week he's ready to die on this hill. He was so withering about that notion in his latest commentary that we hesitate to bring it up: "We think the 'supply matters' view is based on nothing more than intuition. People feel more comfortable when they can frame their views around something that they think they know. It's an approach that regularly fails."

The second battle-cry: A pickup in inflation will drive yields higher. Major's not impressed by this one, either. The Fed's average inflation targeting regime means it won't respond until the rate holds above 2% for some time, and then only if it's accompanied by a labor-market recovery. Indeed, HSBC reckons that inflation and the bond market will "decouple" under the Fed's new approach, with modest increases being absorbed by a decline in real yields. "The focus on the monthly inflation data ignores what really matters, which is the rate of unemployment."

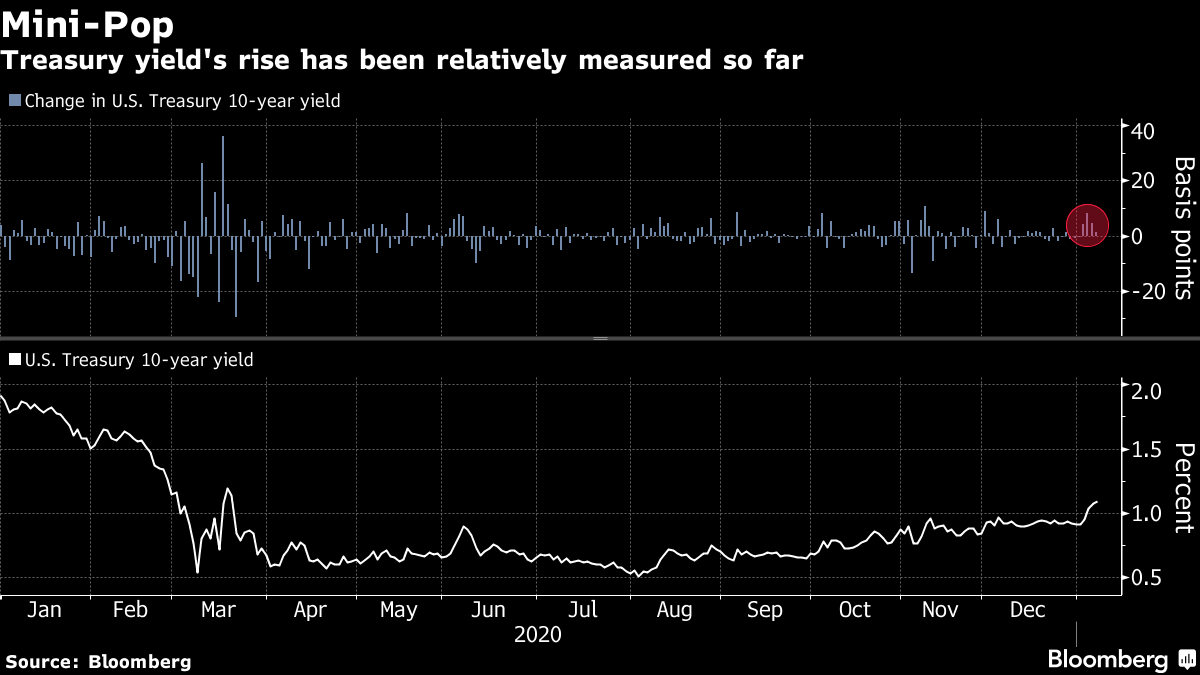

So the stronger case behind the recent rise in yields is that increased fiscal aid, and a likely infrastructure package, can support employment and spur demand. That's the kind of recovery we didn't get in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis because the austerity mavens in Congress snapped the purse shut after the 2009 $787 billion package, leaving the Fed in charge of stimulus. This time should be different if Democrats unite around a generous spending commitment. Goldman Sachs has adjusted its growth forecasts for an additional $750 billion in aid. Their economists now see the U.S. economy growing 6.4% this year, versus 5.9% before the Georgia results. There hasn't yet been a rush of strategists revising their yield forecasts -- Bloomberg's mid-December survey pitched the 10-year at 1.21% by year end. Even as it climbs above 1%, the benchmark global yield still has a way to go to breach its March high of 1.27%, let alone where it began the year at 1.9%. SocGen's Subadra Rajappa says a nearly 40bps increase since early November is no small beer in the context of weak economic data, rising Covid-19 infections and the Fed buying $80 billion a month of Treasuries. She's now expecting the rate to settle in a new range between 0.9%-1.10%, with the next push higher to come in the second half. "With the elections now behind us the work of getting additional pandemic relief, coordinating vaccines and facilitating a road to recovery begins for the Biden administration."

For its part, HSBC declares it's sticking with a bold call for 0.75% at the end of 2021 and 2022. "For a bearish view on Treasuries to be right, the Fed effectively has to indicate higher rates ahead of its stated forward guidance." But... InflationBefore we get to that topic, an interval on inflation. While things aren't getting out of hand, markets are definitely pricing in a stronger increase in price pressures than they have for the past two years. The rise in nominal yields coincides with higher breakeven rates -- a measure of the market's expectations for consumer price inflation, derived from inflation-linked bonds. The 10-year breakeven hit its highest point in more than two years, at 2.11% this week. That's substantial, and probably welcome to policy makers as an endorsement of their commitment to support the recovery. The rising trend in these rates since March's upheaval is proving persistent. At this stage it's not an outlook over the next decade that squarely meets the Fed's criteria for tighter policy. Translated to the central bank's preferred personal consumption expenditure measure of inflation, it's still a little shy of target. And Richmond Fed President Thomas Barkin this week expressed what's become a familiar mantra among his colleagues, saying price pressures are still to the downside, or, more plainly: "It is hard to find inflation in the numbers." That's not a controversial stand to take in the global context: The euro area just recorded headline CPI of -0.3%.  Another point of note among these inflation measures is the bump in real yields since the Georgia races. Ten-year real yields reached an all-time low of -1.12% in the new year. This week has seen a bounce as much as 8 basis points, coinciding with a rally in the dollar. That's something that might hold the Fed's attention as it settles into spectator mode, allowing fiscal policy to take its course. Taper-bombIt's too early to talk about this. But the Fed's balance sheet has a habit of becoming big news without much warning. And the Atlanta Fed president -- a current voter on Fed policy -- dropped the taper-bomb a couple of times already this year, raising the possibility of a pullback in asset purchases this year, or "sooner than people expect." With this in mind, traders are having to wrap their heads around some double think. As our reporter Vivien Lou Chen noted this week, it's risky to go heavily short Treasuries as the Fed can at any point decide to skew its purchases to longer-dated bonds. "It's hard for a trader to have any conviction, when you are just one announcement away from the Fed crushing your trade," said Patrick Leary, a senior trader at Incapital. "You don't want to put it all out there or ride a trade for too long." This adherence to Trading 101: Don't Fight the Fed, has played a large role in preventing any spike in yields. Several policy makers this week said they're prepared to tolerate a rise in yields in line with improving growth -- it's the kind of volatility that threatens financial conditions that would warrant action on bond purchases. But the Fed is also likely to start trimming those purchases at some point, and the merest hint of that back in 2013 was a windfall for Treasury bears. Other policy makers have suggested tapering is unlikely this year, but voters aren't exactly avoiding the conversation. The Chicago Fed's Charles Evans said "some type of tapering" was possible late this year or early next, but he's waiting until mid-2021 to get a clearer picture. His colleague in Dallas, Robert Kaplan, envisaged a "point at which it'll be much healthier for the economy and for markets to be weaning off some of these extraordinary measures." All of which makes the Fed's messaging pretty important, though no one really thinks it has strong plans for any action just yet. At least nothing other than monitor the economic impact of any fiscal efforts, and keep an eye on financial conditions, which by Goldman Sachs' reckoning last week were the easiest in the three decades that the firm's been tracking them. Bonus PointsSingapore's Changi Airport reinvents itself for a return of business travel. The pandemic pushed 32 million people globally into extreme poverty. Your moment of zen. Compare and contrast, law enforcement responses to two DC protests. How Neil Sheehan got the Pentagon Papers. Oh, and Brexit is done. |

Post a Comment