Who's buying GameStop?Yesterday many big retail brokerage firms told their customers that they would no longer be able to buy GameStop Corp. stock because it was getting too crazy. This led to a lot of outrage from people who are famous and online: Among others rebuking the moves by the brokerages were Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D., N.Y.), Sen. Ted Cruz (R., Texas), billionaire Mark Cuban and Dave Portnoy, the founder of the popular digital media company Barstool Sports Inc. Mr. Portnoy was one of countless individual investors who dove into the markets this year, often streaming his trades to his followers on Twitter. Ms. Ocasio-Cortez tweeted: "We now need to know more about @RobinhoodApp's decision to block retail investors from purchasing stock while hedge funds are freely able to trade the stock as they see fit."

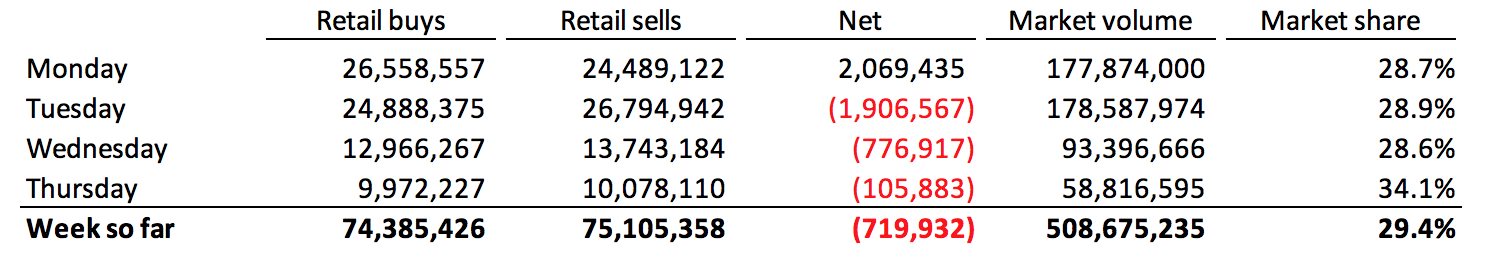

The popular story here is that small-time retail investors, who stereotypically trade stock on the Robinhood app and egg each other on in the WallStreetBets Reddit forum, have been pushing up the stock of GameStop for a few weeks, and they got it to pretty dizzying heights: GameStop started the year at $18.84 per share; at one point yesterday morning it traded at $483, up almost 2,500%. They are doing this partly for fun and partly for profit but also, especially, to mess with the hedge funds on the other side of the trade, who had bet against GameStop by shorting the stock and who suffered and surrendered as it went up. We have, uh, talked about this a bit this week. Given that story, it was natural to get mad at Robinhood—other brokerages too, but mostly Robinhood—for bailing out the hedge funds and stopping the retail traders from having their fun. The hedge funds who were betting against GameStop still get to trade however they like, and had a good day yesterday; the Reddit heroes who were battling them were summarily ejected from the game. Seems unfair. You could tell a different version of the story, a more traditional one really. In this one, innocent retail investors who have succumbed to Robinhood's gamification of markets, and who have been bamboozled by the maniacs on WallStreetBets, have been buying GameStop stock at ridiculous prices and hoping to unload it on a greater fool. In this story GameStop is more or less a classic pump-and-dump scheme; to protect retail investors, they must not be allowed to buy the stock anymore. "These small and unsophisticated investors are probably going to get hurt by this," said Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth William Galvin, as he called for the stock exchange to consider suspending trading in GameStop for a month. In that story, Robinhood saved its clients from themselves, though at the expense of its other clients who had already bought the stock. In a classic pump-and-dump, if there are no new buyers—because their brokers won't let them buy anymore—then the stock collapses, and the last buyers are left holding the bag. The stock collapsed, I guess, but it's all relative. It closed yesterday at $193.60, down 60% from yesterday's high, but also up 31% from Tuesday's close and up 928% so far in January. The stock's doing great, really. The … near total prohibition on retail buying? … didn't hurt it as much as you might expect. (After the close, Robinhood "said clients would be able to make limited purchases of some of the companies that it blocked, but did not provide further details," and the stock rallied; it opened at $379.71 today.) So that's a little weird. One natural conclusion to draw from it might be, well, maybe a lot of the move in GameStop's price was not caused by retail traders on Robinhood and Reddit, but by professionals, hedge funds and proprietary trading firms and professional day-trading shops. When retail buying was shut down, other buying continued. Here is some suggestive data on that. Many of the big retail brokerages, including Robinhood, route a lot of their customer orders to Citadel Securities, so it ends up seeing a large percentage of retail trades in U.S. stocks. It can see if retail traders are mostly buying or mostly selling or mostly pretty balanced. You might expect—I certainly expected—to see that retail traders were buying more than they were selling this week. The stock seemed to be rocketing up on frenzied retail sentiment, and the posters on WallStreetBets were all claiming that they would never sell and keep buying until it hit $1,000. But here's what Citadel Securities' retail flow looked like in GameStop this week:[1]  Source: Citadel Securities Retail investors were net buyers on Monday but net sellers for the rest of the week (through yesterday), and all in all quite balanced: About 49.8% of retail orders (that Citadel Securities saw) were to buy, and 50.2% were to sell. What do you make of that? One reading would be: "Retail investors on Reddit might have started the GameStop rally, but they're not piling into this stock now, and the price action this week is coming from professionals." Or as one Twitter user put it, "past the retail ignition, the rocket ship was mostly intra-fast money warfare." This story doesn't exactly tell you who the professionals are, whether they're traditional Wall Street (hedge funds, etc.) or algorithmic high-frequency traders or just semiprofessional crews of day-traders who don't access the market through traditional retail brokers. Someone other than Robinhood traders, anyway.[2] You could tell a related story like: "Retail investors on Reddit started the rally to squeeze professional short sellers, and then this week the professional short sellers capitulated and started buying the stock at even higher prices from those redditors, who claimed victory and took profits." This is probably true, at least in part. It also matches the popular story reasonably well, except that in the popular story the short squeeze is in the future, and the Reddit traders are supposed to be holding firm so that short sellers can't cover even at recent high prices. Another reading would be: "Lots of retail investors are piling into this stock, and the price action is coming from them, but they're mostly buying stock from other retail investors."[3] Those other retail investors could be normal people who bought 100 shares of GameStop in 2005, forgot about them, and then remembered and sold them into this rally, or they could be Reddit posters who got in early, pumped the stock on WallStreetBets, and then happily got out as more people piled in to buy. I don't want to make too much of this. There are always as many buyers as sellers, so it's not really a surprise that about half of the retail investors playing the GameStop game were buying and about half, or a little more, were selling. GameStop has about 69.7 million shares outstanding, but almost 180 million shares traded on both Monday and Tuesday, meaning that on average each GameStop share turned over 2.5 times on each of those days. Of course people were buying and selling and selling and buying; the fact that the retail crowd was not overwhelmingly on one side is pretty much a mathematical requirement. Still I think this complicates the popular story of "everyone on Robinhood was buying GameStock at once, and none of them were selling, so the stock went up in a demonstration of the power of small-time traders to take on Wall Street." Retail investors were both buying and selling, and selling a bit more than they were buying, as the stock was rocketing and (some!) hedge funds were losing their shirts. This also, incidentally, helps clear up one of the biggest mysteries, for me, in modern equity market structure. We talk a lot around here about "payment for order flow," the system by which Citadel Securities (and other wholesalers) pays Robinhood (and other retail brokers) to trade with its customers' orders. I like to tell a fairly textbook version of that story. Market makers stand ready to buy or sell stock from or to customers; they try to buy for a bit less than they sell at, and pocket the spread. If you go out into the market and say "hey I'll buy anyone's stock for $10," and a really smart hedge fund comes to you and sells you stock for $10, that's probably bad. You've probably made a mistake. The hedge fund is selling you the stock for $10 because it knows it's worth $8. This is called "adverse selection." More subtly, if a really big mutual fund comes to you and sells you stock for $10, that also may be bad. The mutual fund is probably selling lots of stock, because it's so big; it sells you a little, then sells a little more, then a little more, until it pushes the price down to $8. The mutual fund isn't necessarily smart, but by virtue of being big and doing big trades, it moves the price; if you are on the other side of its trades, you get run over. This is also a kind of adverse selection: You buy at $10 and are stuck selling at $8. Part of the spread that market makers earn in public markets—the difference between their buying and selling prices—compensates them for adverse selection, the risk of being run over by a counterparty who knows something they don't. Market makers, the textbook theory goes, would much rather trade with retail orders. Retail investors generally don't know much, so if you buy stock from them you're probably not making a mistake. And retail orders are generally small and uncorrelated: One investor buys a little, another comes along a moment later and sells a little, it's all pretty random, and you're not facing an avalanche of steady sell orders that push the price down. Trading with retail is so nice that market makers—wholesalers—will both give retail orders a tighter spread (pay more to buy their stock, charge less to sell stock to them) and pay their broker for the privilege of doing it. The rise of Robinhood-y meme stocks, it seemed to me, changed that dynamic. If everyone on Robinhood decides all at once to buy Tesla Inc. stock, and Tesla shoots up, then the wholesaler on the other side of that trade is getting run over. It's selling Tesla at $700 and $750 and $800 and $850, selling more and more at higher prices without ever being able to buy back at lower prices from other retail investors who want to sell. No retail investor wants to sell; everyone on Robinhood wants to do the same thing at the same time. It seemed to me that Robinhood orders are now worse than orders from big mutual funds and hedge funds, more likely to move the price against the market maker who interacts with them. Why would anyone pay to be on the other side of that? But ... nope? That stereotype of new-style Robinhood trading might just be wrong. Even in one of the wildest melt-ups in stock-market memory, the absolute epitome of insane one-way retail buying, actual retail order flow was pretty balanced. People were buying, people were selling, it was fine, you could still make money trading with them. Why did Robinhood stop them?You don't think about it much, but every stock trade involves an extension of credit. You see a price on the stock exchange and push a button and instantaneously get back a confirmation that you bought some shares of stock, but you actually get the shares, and pay the money for them, two business days later. This is called "T+2 settlement," and it might seem a little silly in an age when a "share of stock" is an entry in an electronic database and "money" is also an entry in an electronic database. Why not just update the databases when you push the button? T+2 settlement feels like a vestige of the olden days, when traders agreed to trades on the stock exchange but then had to go back to their vaults to dig up stock certificates to hand over in exchange for sacks of cash. Back when I worked on Wall Street it was T+3. These days it is not hard to find people who want to talk to you about moving to instantaneous settlement on the blockchain. Bitcoin trades settle immediately. But U.S. stocks, for now, settle T+2. This means that the seller takes two days of credit risk to the buyer.[4] I see a stock trading at $400 on Monday, I push the button to buy it, I buy it from you at $400. On Tuesday the stock drops to $20. On Wednesday you show up with the stock that I bought on Monday, and you ask me for my $400. I am no longer super jazzed to give it to you. I might find a reason not to pay you. The reason might be that I'm bankrupt, from buying all that stock for $400 on Monday. The way that stock markets mostly deal with this risk is a system of clearinghouses. The stock trades are processed through a clearinghouse. The members of the clearinghouse are big brokerage firms—"clearing brokers"—who send trades to the clearinghouses and guarantee them. The clearing brokers post collateral with the clearinghouses: They put up some money to guarantee that they'll show up to pay off all their settlement obligations. The clearing brokers have customers—institutional investors, smaller brokers—who post collateral with the clearing brokers to guarantee their obligations. The smaller brokers, in turn, have customers of their own—retail traders, etc.—and also have to make sure that, if a customer buys stock on a Monday, she'll have the cash to pay for it on Wednesday.[5] This is not stuff most people worry about most of the time. Generally if you buy a stock on Monday you still want it on Wednesday; even if you don't, we live in a society, and you'll probably cough up the money anyway because that's what you're supposed to do. But at some level of volatility things break down. If a stock is really worth $400 on Monday and $20 on Wednesday, there is a risk that a lot of the people who bought it on Monday won't show up with cash on Wednesday. Something very bad happened to them between Monday and Wednesday; some of them might not have made it. You need to make sure the collateral is sufficient to cover that risk. The more likely it is that a stock will go from $400 to $20, or $20 to $400 for that matter,[6] the more collateral you need. Anyway why did Robinhood (and other retail brokers) shut down purchases of GameStop (and other meme stocks)? Here is a good explanation from Bloomberg News: One key consideration for brokers, particularly around high-flying and volatile stocks like GameStop, is in the money they must put up with the DTCC while waiting a few days for stock transactions to settle. Those outlays, which behave like margin in a brokerage account, can create a cash crunch on volatile days, say when GameStop falls from $483 to $112 like it did at one point during Thursday's session. "It's not really Robinhood doing nefarious stuff," said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Larry Tabb. "It's the DTCC saying 'This stuff is just too risky. We don't trust that these guys have the cash to be able to withstand settling these things two days from now, because in two days, who knows what the price could be, it could be zero.'" The trouble on Thursday began around 10 a.m., when after days of turbulence, the DTCC demanded significantly more collateral from member brokers, according to two people familiar with the matter. A spokesman for the DTCC wouldn't specify how much it required from specific firms but said that by the end of the day industrywide collateral requirements jumped to $33.5 billion, up from $26 billion. Brokerage executives rushed to figure out how to come up with the funds. Robinhood's reaction drew the most public attention, but the firm wasn't alone in limiting trading of stocks such as GameStop and AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. In fact, Charles Schwab Corp.'s TD Ameritrade curbed transactions in both of those companies on Wednesday. Interactive Brokers Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley's E*Trade took similar action Thursday.

And here is the Wall Street Journal: At least three brokerages said the trading restrictions stemmed from mandates from their clearing firm, which process the securities on the back end after a user executes a trade with their brokerage. Webull Chief Executive Anthony Denier said his platform's clearing firm, Apex Clearing Corp., notified him Thursday morning that Webull needed to shut off the ability to open new positions in certain stocks. Otherwise, Apex wouldn't be able to settle the trades, he said. ... Mr. Denier at Webull said the restrictions originated Thursday morning when the Depository Trust & Clearing Corp. instructed his clearing firm, Apex, that it was increasing the collateral it needed to put up to help settle the trades for stocks like GameStop. In turn, Apex told Webull to restrict the ability to open new positions in order to prevent trades from failing, Mr. Denier said. DTCC, which operates the clearinghouses for U.S. stock and bond trades, is a key part of the plumbing of financial markets. Usually drawing little notice, it facilitates the movement of stocks and bonds among buyers and sellers and provides data and analytics services. In a statement, DTCC said the volatility in stocks like GameStop and AMC has "generated substantial risk exposures at firms that clear these trades" at its clearinghouse for stock trades. Those risks were especially pronounced for firms whose clients were "predominantly on one side of the market," a reference to brokers whose customers were heavily betting for stocks to rise or fall, rather than having a mix of positions.

Robinhood drew down "at least several hundred million dollars" from its bank credit lines and "said on Thursday that it was raising an infusion of more than $1 billion from its existing investors." The volatility of those stocks is approaching infinity as their trading volume increases, so the traditionally mild and technical credit risk around settling trades has become real and scary. Brokerages have to put up more money to guarantee against that risk, and also think about ways to prevent the risk from coming true. "Stop buying super volatile stocks" is one obvious way. It has become expensive and risky to be a broker for the meme stocks, so some of them tried to stop.[7] There are conspiracy theories floating around, because this feels weird, but it is actually pretty normal? Byrne Hobart writes: In a way, WallStreetBets' GameStop experience is the culmination of efforts to give retail investors an institution-quality experience. As Josh Brown points out, WallStreetBets is a scaled-up version of an idea dinner. It might seem more raucous than how financial professionals behave, but competitive hyper-bullishness and hyper-boorishness are not restricted to reddit and Discord. Most individual investors don't lever up enough, or get into crowded enough trades, that their broker raises collateral requirements at the most inconvenient possible moment, but this does happen to institutions. And professional investors often develop somewhat conspiratorial instincts—the more research you've done before a trade, the more losing money on it feels like the result of sinister forces trying to thwart you. After many layers of indirection, WallStreetBets and Robinhood have given retail investors a version of the professional experience.

What about the short sellers?Short selling—borrowing stock and selling it, hoping that it will go down and you can buy it back at a profit—is a hard business. It is a hard business because most stocks go up most of the time: If you are mediocre at buying stocks you will make money, but if you are mediocre at shorting them you will lose money. (In fact if you are great at shorting them you will also lose money, but in a good way?) It is a hard business because stocks can only go down 100% but can go up any percentage you want, and sometimes (GameStop) they do: If you are terrible at buying stocks the worst you can do is lose your whole investment, but if you are terrible at shorting stocks the worst you can do is lose everything you own. It is a hard business because you have to borrow the stock and post collateral and pay fees, and as the stock goes up you have to post more collateral and pay more fees: Even if you are right about a short bet, and the company ends up going to zero, if it goes up a lot first you might be forced out of your position and lose money. Especially, though, it is hard because everyone hates you? I have nothing intelligent to say about this. It seems to me that selling stock is as legitimate as buying it, that betting that prices will go down is as legitimate as betting that they'll go up, that for prices to be accurate and capital allocation to be efficient you need to let skeptics express their opinions, and that anyway a lot of actual short selling is for helpful market-plumbing reasons (market making, hedging options, etc.) rather than big negative bets against companies. Lots of people reading this are like "duh yes of course." Lots of other people are like "no it is mean to root against companies and fraud to sell stock you don't own." (One of those people is the richest man in the world, who got that way in part by selling cars he hadn't built.) Some of them are typing emails to me right now saying "but surely it's illegal that people are short 140% of GameStop's stock," even though I keep explaining that it isn't.[8] I do not really understand this perspective, I suspect they don't understand mine, we will just have to agree to disagree, and it is so boring to write about. One result of everyone hating short sellers is that professional short sellers tend to be cantankerous sorts, but that's not all that unusual in the financial industry. Another result is that there are occasional regulatory threats against short sellers: When anything bad happens, it is politically tempting to blame short sellers and try to crack down on them. Every so often regulators do, and that is bad for business, but for the most part, in the U.S., regulators tend to share the "eh short selling is fine" perspective and don't try to ban it, even though lots of people would like them to. One possible reading of the GameStop story is that the people who would like to ban short selling got together to bypass the regulators and ban it themselves. Like, short selling was not illegal last month, and it is not any more illegal now, but perhaps it is impossible now? Just as a populist, aggregation-of-preferences, social-norms-backed-by-sanctions matter, now if you sell stocks short you will be fined millions of dollars, by Reddit, so you might as well not do that. Or maybe you can short stocks, but you can't noisily short them; you can't bet against them and then announce that they're bad to try to drive the price down. Lots of people think that should be illegal, and now it kind of is, not as a matter of actual law but as a matter of, like, community norms backed up by enforcement power. The enforcement power of WallStreetBets taking all your money. I am not being especially serious about this—I do not think that short selling, even noisy or activist short selling, will be permanently ended by a couple of crazy weeks on Reddit—but there is this: Outspoken activist short seller Andrew Left on Friday said that after 20 years, his firm Citron Research will exit the business of writing reports focusing on companies whose value may fall. Via Twitter and YouTube video, Left explained his decision with a headline saying: "Citron Research discontinues short selling research. After 20 years of publishing Citron will no longer publish 'short reports'." Citron said it would focus instead "on giving long side multibagger opportunities for individual investors."

If your business model isn't allowed anymore, you need a new model. "Hopefully we can put our experience to add some sanity, and most of all, some kindness back in this market," Left says in his video. It's a pivot! But! Is! It! Securities! Fraud!No? Lawyers gonna lawyer though: Robinhood can now add a class action lawsuit to its growing list of headaches after it said it would restrict users from trading GameStop and other stocks. A class action lawsuit was filed in New York Thursday, alleging that Robinhood "deprived their customers of the ability to use their service," in an effort "to manipulate the market for the benefit of people and financial intuitions." The lawsuit comes hours after Robinhood informed users that it would restrict a handful of stocks, including GameStop, Blackberry, AMC, and American Airlines, due to "recent volatility." The company also said it would raise margin requirements for some securities. "We continuously monitor the markets and make changes where necessary," Robinhood said.

Here's the complaint. Feel free to read it I guess. Before all this stuff, Robinhood had achieved a certain level of fame for being a retail brokerage that lets you buy all the fun stocks, but whose app crashes when too many people want to buy too many fun stocks. This is not the first time that people have gotten mad online about Robinhood not letting them buy stocks that were going up. Usually it's by accident—the app crashes so you can't buy the stocks you want—and this time it's on purpose, but still. If Robinhood was legally obligated to let you buy all the stocks you want whenever you want, it would have been sued into oblivion long ago. They write the contracts better than that. Elsewhere in securities fraud, here's the latest statement from the Securities and Exchange Commission about all this: The Commission is closely monitoring and evaluating the extreme price volatility of certain stocks' trading prices over the past several days. Our core market infrastructure has proven resilient under the weight of this week's extraordinary trading volumes. Nevertheless, extreme stock price volatility has the potential to expose investors to rapid and severe losses and undermine market confidence. As always, the Commission will work to protect investors, to maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets, and to facilitate capital formation. The Commission is working closely with our regulatory partners, both across the government and at FINRA and other self-regulatory organizations, including the stock exchanges, to ensure that regulated entities uphold their obligations to protect investors and to identify and pursue potential wrongdoing. The Commission will closely review actions taken by regulated entities that may disadvantage investors or otherwise unduly inhibit their ability to trade certain securities. In addition, we will act to protect retail investors when the facts demonstrate abusive or manipulative trading activity that is prohibited by the federal securities laws. Market participants should be careful to avoid such activity. Likewise, issuers must ensure compliance with the federal securities laws for any contemplated offers or sales of their own securities.

I don't know how much that means: If you're manipulating GameStop stock, you're in trouble, but on current evidence I am not all that convinced that anyone is. On the other hand that last sentence is ominous. I have written before that GameStop should sell a ton of stock into this huge demand, both because it would be funny and also because what is the point of a high stock price if not to channel money to a company that can use it? But I have also written that, if I were GameStop's board of directors, I'd be nervous about actually doing that: I think it's probably fine to sell stock to people who want to buy it at deranged levels, but it kind of looks like securities fraud. This is the SEC saying, well, be careful about selling stock, you don't want it to look like securities fraud. Who is Roaring Kitty?Amazing: A YouTube streamer who helped drive a surge in the shares of GameStop Corp is a 34-year-old financial advisor from Massachusetts and until recently worked for insurance giant MassMutual, public records and social media posts show. Keith Patrick Gill is the person behind the Roaring Kitty YouTube streams which, along with a string of posts by Reddit user DeepF***ingValue, helped attract a flood of retail cash into GameStop, burning hedge funds who had bet against the company and roiling the broader market.

Absolutely spectacular. (Here is a profile; here is an interview.) I hope he showed up at client meetings in a headband and sunglasses with a glass of champagne in one hand and a chicken tender in the other. I hope he was like "never mind life insurance, man, you gotta buy GameStop calls! Get those tendies!" And then I hope the clients were like "what" and MassMutual fired him and he just went and did the thing. He was up some $33 million as of yesterday's close. The guy behind one of the greatest trades of our time was giving out financial advice for MassMutual, and somehow they let him go. What about the World Wide Robin Hood Society in Nottingham?I like the energy here:  I followed them. I imagine them, like, dusting the feathered cap at the Robin Hood Museum and wondering why their phones are blowing up. "I say, do you know anything about a gamma squeeze? Perhaps it's an archery technique? And why is everyone so cross with a chap named Melvin?" Here is a "Robin Hood Reality Check" on their website that I found very soothing; it has almost nothing to say about margin requirements for highly volatile stocks. "On October 9th, 1966," I learned, "the then Sheriff of Nottingham, Councillor Percy Holland, actually officially pardoned Robin Hood and stated that he 'shall be welcome in the City of Nottingham at all times!'" That's nice. Things happenDo they, though? If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! [1] "Retail buys" and "retail sells" are how many shares' worth of buy and sell orders they got from retail brokerages; "net" is how many shares retail net bought (or, if negative, net sold). (I.e. the first column minus the second.) "Market volume" is just the consolidated volume in GameStop that day, and "market share" is how much of that volume Citadel Securities executed for retail. (I.e. the sum of the first two columns divided by the fourth.) [2] Or just retail traders who don't interact with Citadel, I guess. Maybe you could tell a story about how Citadel Securities' flow is somehow unrepresentative of what retail generally is doing with GameStop, though I'm not sure what that story would be. Citadel gets, for instance, a lot of Robinhood orders. [3] Remember if you look at the market as a whole you will always find zero net buys/sells; there are always exactly as many buyers as sellers. And yet prices go up and down anyway. If retail investors were only trading with themselves, but getting more enthused, then buyers would bid higher prices and sellers would only be willing to sell at higher prices, so the stock would go up with zero net retail buying. [4] And vice versa; the buyer takes two days of risk that the seller won't produce the shares at settlement. [5] That's not, like, a conceptually difficult thing to do; you could require her to have the money in her account on Monday. You might not, though, if you wanted to aggressively compete for the business of active traders. Or you might, as Robinhood does, let her use the proceeds of a sale before the sale settles, increasing your own credit exposure. [6] Because, again, the seller is obligated to show up with the stock in two days, and if the stock rockets up the seller might not show up. If for instance the seller was short. This is called a "fail," and people talk a lot about it for stocks that are heavily shorted, like GameStop. [7] Of course, if a broker is also giving *margin loans* against meme stocks, that is a very direct and straightforward and, now, terrifying credit risk. When GameStop hit $483 yesterday morning, in theory, a trader in a margin account could have borrowed $241.50 against it. By yesterday afternoon the stock was at $193.60, the trader had lost 100% of her equity and the margin lender was down $47.90. You can't give margin loans against stocks with 500% realized volatility, come on. Yesterday Robinhood "also raised margin requirements for certain securities." [8] It's in footnote 3 here, but let's just retype it. "There are 100 shares. A owns 90 of them, B owns 10. A lends her 90 shares to C, who shorts them all to D. Now A owns 90 shares, B owns 10 and D owns 90—there are 100 shares outstanding, but 190 shares show up on ownership lists. (The accounts balance because C owes 90 shares to A, giving C, in a sense, negative 90 shares.) Short interest is 90 shares out of 100 outstanding. Now D lends her 90 shares to E, who shorts them all to F. Now A owns 90, B 10, D 90 and F 90, for a total of 280 shares. Short interest is 180 shares out of 100 outstanding. No problem! No big deal! You can just keep re-borrowing the shares. F can lend them to G! It's fine." |

Post a Comment