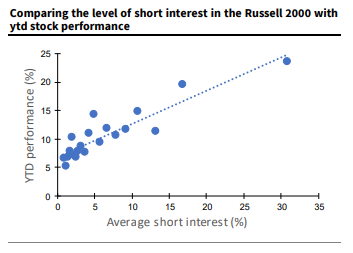

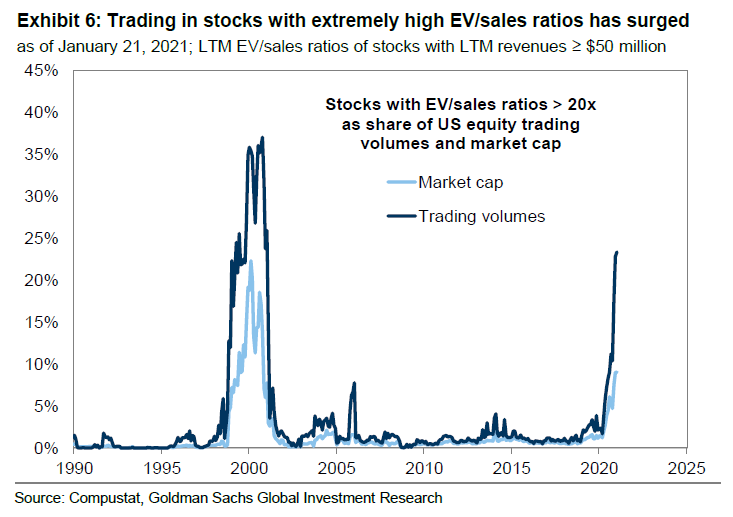

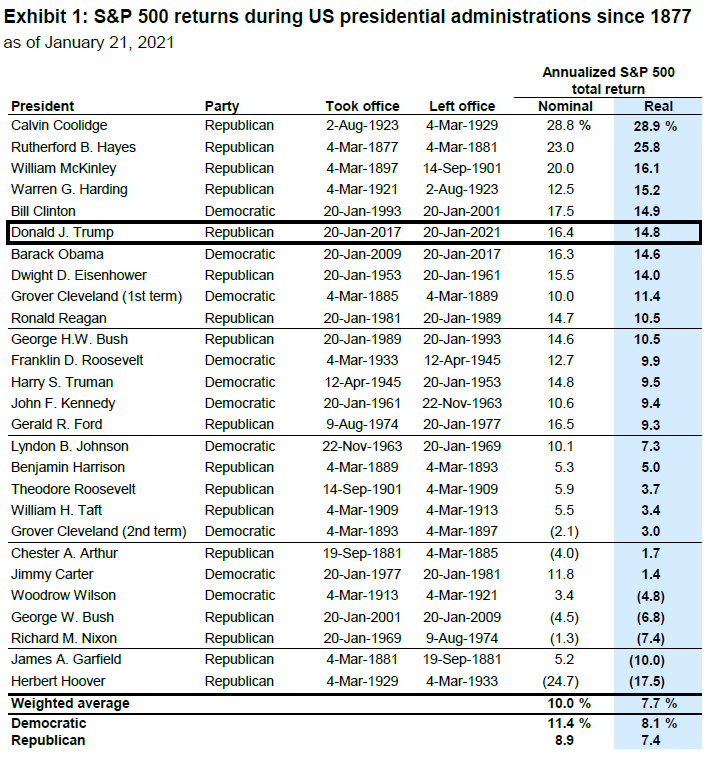

Keeping It ShortAfter some complaints about the length of yesterday's newsletter, I will try to keep this one short, and that's appropriate because I need to delve into the world of short-selling. For the uninitiated, short-selling involves borrowing a stock and then selling it. If it goes down, the short-seller can pocket a permanent profit by buying it back for a lower price and giving it back to the owner. If it goes up, the potential losses are infinite. As stocks tend to go up over time, and short positions cost more than long positions because of the need to pay interest to the owner, short-selling understandably tends to be a small proportion of the total market. However, shorting still plays a critical role in maintaining market hygiene. At a broad level, short positions can be part of risk management, and they can also help to amplify the skills of quantitative stockpickers, by pairing under- and over-valued stocks and betting on the difference to narrow. The possibility of short-selling also helps keep the market honest by giving some investors an incentive to find companies that are too expensive and bringing their share prices down. Short-sellers can often be essential to revealing fraud. Despite this, short-sellers tend to be unpopular. Back in the week that Lehman Brothers collapsed in 2008, for example, there was an outcry, and one of regulators' first acts was to ban short-selling on a range of financial companies. In the long run, those stocks still fell a lot further. And now that authoritative histories of that era are being written, it's noticeable that almost nobody puts any blame on short-sellers. All they were doing, we can now see, was betting on the eventual doom of companies that were already doomed. So although some schadenfreude is inevitable when short-sellers get into trouble, it is generally misplaced. And that is particularly the case now. They are in trouble to a quite alarming extent. First, there is the amazing story of GameStop Corp., a video retailing company that attracted the attention of many short-sellers after a swift appreciation last year, leading to a coordinated "short squeeze" in which indignant followers of a forum on Reddit banded together to buy the stock and inflict ever more pain on the shorts — to the tune of losses of some $6 billion. The results almost defy description. I suggest you read some of the reports I have linked here (particularly this vintage explanation from Matt Levine), and gaze in awe on this chart, which shows that GameStop stock has now left even bitcoin in the dust:  To be clear, there is no possible way to justify a 1,100% increase in GameStop's share price since the beginning of last year. This is a symptom of something that has gone seriously awry — and I predict that it will also make an extremely entertaining blow-by-blow book before the year is out. GameStop is an extreme example, to be sure, but it is far from a one-off. So far this year, betting on stocks with a heavy level of short interest (in other words, companies that have become popular targets because they seem to be overvalued) has evidently become a popular strategy, and a very lucrative one. The following chart, from Societe Generale SA's quantitative strategist Andrew Lapthorne, ranks small-cap companies in the Russell 2000 index by their level of short interest, and looks at how this affected performance in the year to Jan. 22 (last Friday) by which point the overall index had gained almost 10%. Remarkably, the most shorted stocks showed a gain of almost 25%, while the next most shorted were up by 20%. Either specialist short-sellers were spectacularly ill-advised in their targets or (far more likely), there is plenty of speculative money seeking to bet against them:  This amplifies a pattern that had already gone into overdrive last year. It isn't surprising that short-sellers generally did badly over the last decade; you would expect them to struggle during a bull market when the direction is upward. But the following chart, which shows Hedge Fund Research's HFRX index of specialist short-bias hedge funds relative to the S&P 500, shows that this turned into brutal underperformance last year:  This unhealthy trend is beginning to have effects. One of Monday's other big news stories was the announcement that the hedge fund Melvin Capital had accepted an injection of $2.75 billion from its rivals Citadel and Point72 Asset Management (run respectively by industry titans Ken Griffin and Steven A. Cohen), after disastrous short positions left it with losses of 30% for the year to date. This brings back memories of the summer of 2007, when the early tremors of the financial crisis led to sudden and bizarre losses for hedge funds with specific strategies that suddenly unwound and came in for attack. Even Goldman Sachs Asset Management had funds that needed to be rescued with extra capital of $3 billion. When big well-financed players suddenly take losses on this scale, it is a "tell" that market trends have been taken too far. There are, of course, many other signs of excess. But a critical point can be missed. It is commonplace to attribute what is going on to low bond yields, and these of course help justify some lofty valuations for the stock market. But low bond yields don't make it so much of a better idea to engage in a coordinated speculative short squeeze in a relatively small company. Fun and games like this are a symptom of too much liquidity leaving traders emboldened to take trades to excess. Another illustration comes from Goldman. The following chart shows the market cap and trading volumes in hugely expensive stocks that enjoy an enterprise value of more than 20 times sales. Normally, there aren't many such companies. Now, there are enough for traders to enjoy themselves. Minimal interest rates helped valuations of these stocks to take off, but it is excess liquidity that then allowed trading volumes to go to the moon.  Those interest rates remain low for a reason and while they are low, sky-high stock valuations can continue. But low interest rates don't justify the high jinks of traders forming flash mobs to pile into already wildly overvalued stocks and squeeze short-sellers. A correction sooner rather than later would be healthy. It might even bring a bitter smile to the face of some short-sellers. Presidential MarketsAs the House of Representatives insists on keeping President Trump a live political issue by impeaching him, let's return to the issue of just how well the stock market did on his watch. First, a health warning: Stock market strength is almost no indicator of how well a president did in office. Too much is dependent on chance, the actions of others, and on valuation at the time the incumbent takes office. But as the 45th president insisted on judging himself by the stock market, it is fun to see how he compares. There is good and bad news for Trump from the following league table of all the presidents since 1877, published by Goldman Sachs's David Kostin. The good news is that he appears high in the rankings, and overtakes Barack Obama; the bad news is that he remains behind Bill Clinton, along with four presidents who have generally gone down in history as mediocrities. The list is headed by Calvin Coolidge, who by leaving office in March 1929 showed that the best way to get a great return on your presidential watch is to preside over an epic speculative bubble, and then step down just as it's about to burst.  Goldman has ranked presidents by annualized average returns over their whole terms, allowing brief presidencies like Ford's or Garfield's to be compared with FDR's. Also, crucially, they did the ranking in real terms, after inflation. This makes an immense difference because a number of 19th century presidents oversaw outright deflation, meaning that their real returns were better than their nominal returns. The hapless Herbert Hoover remains anchored at the bottom of the list, but accounting for the savage deflation from 1929 to 1933 does help bring his nominal return up from minus 24.7% to a slightly more respectable minus 17.5%. For the man who will shortly face the judgment of the Senate, the judgment of the market was that he was better than some greatly respected names from history, including Ronald Reagan and both Roosevelts, but also that he wasn't as good as the likes of Rutherford B. Hayes and Warren G. Harding. Which gets us back to the most important point, which is that the stock market is no way to judge a president. Biden shouldn't spend too much time looking at the S&P during his term. Survival TipsBring me my bow of burning gold, bring me my arrows of desire, bring my my spear, O clouds unfold, bring me my chariots of fire. William Blake's Jerusalem is a great poem, even if his idea that Jesus once walked around England's "dark satanic mills" was nonsense. Beyond a great hymn that often sees service as England's national anthem, it also gave us the title of a great movie. I watched Chariots of Fire with the family at the weekend, for the first time in more than three decades. It's really, seriously good; exciting and inspiring without ever being mawkish or sentimental, brilliantly scripted and wonderfully acted by an ensemble cast. The famous theme tune doesn't come up that often. It can also be appreciated by all the family. It's well worth streaming in the grimmest weeks of winter. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment