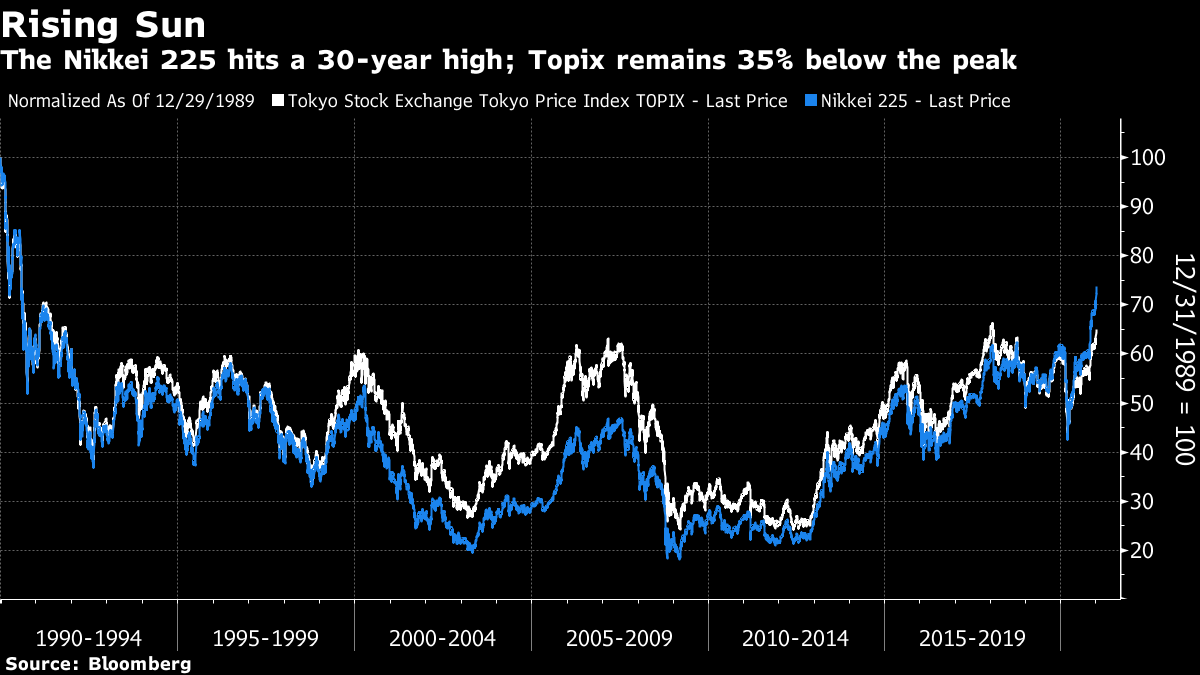

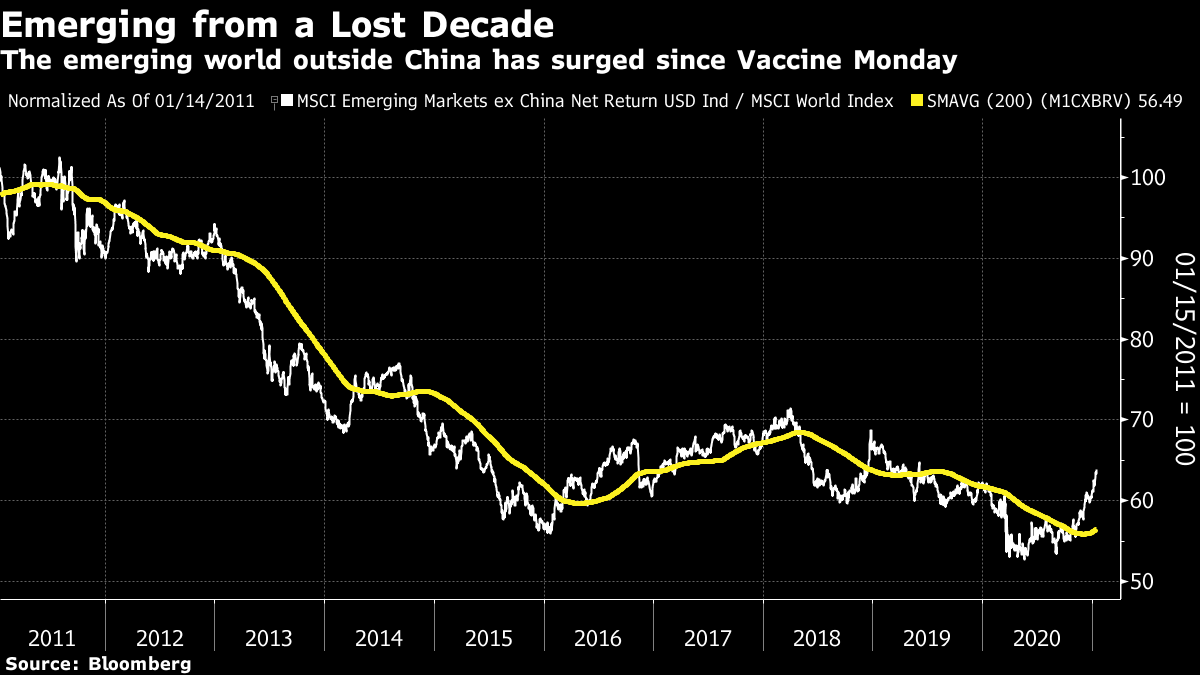

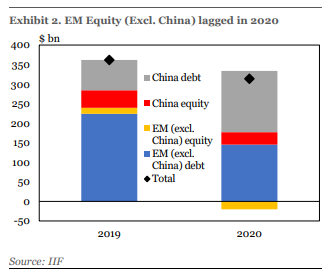

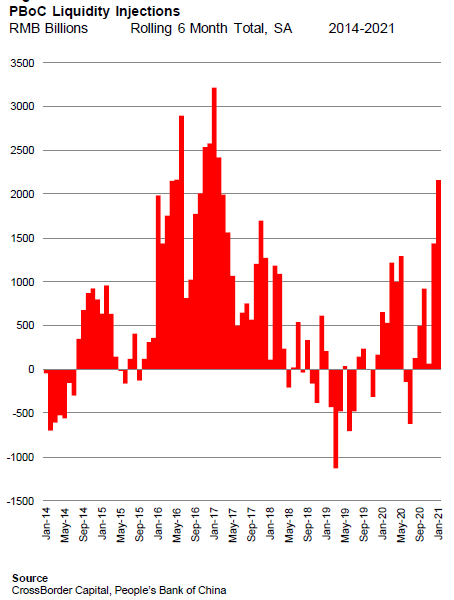

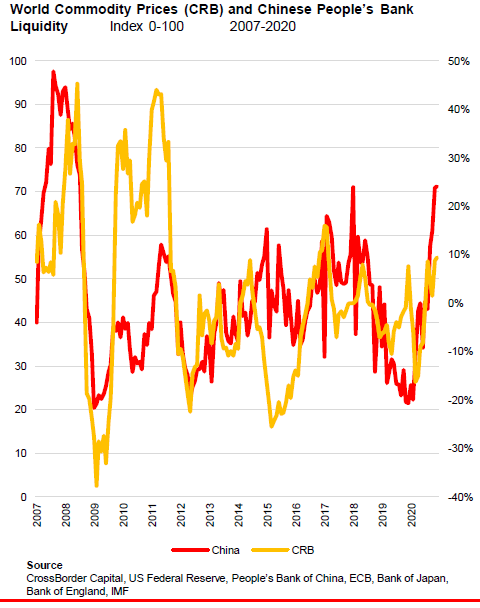

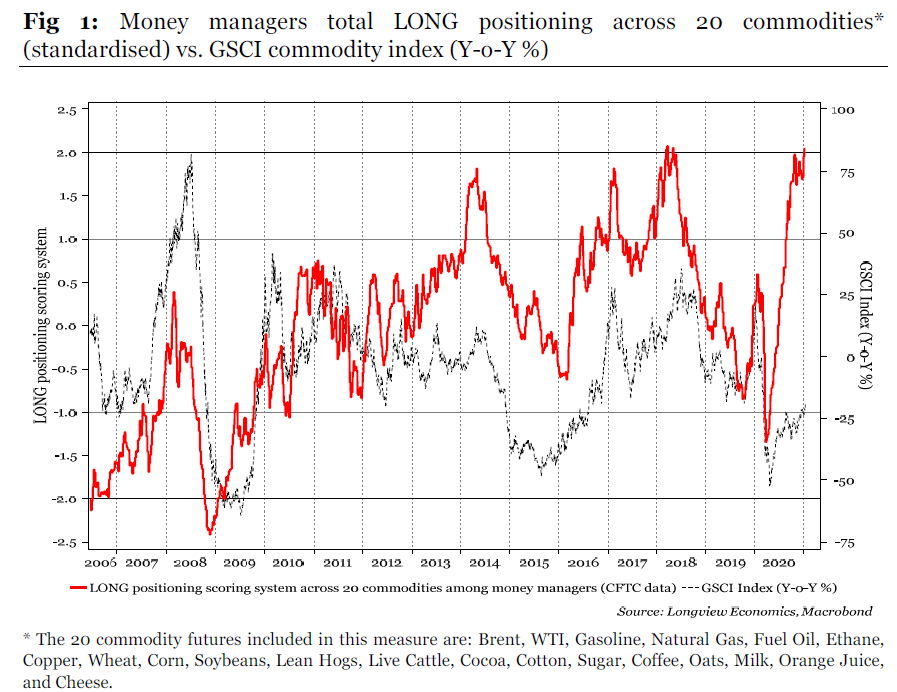

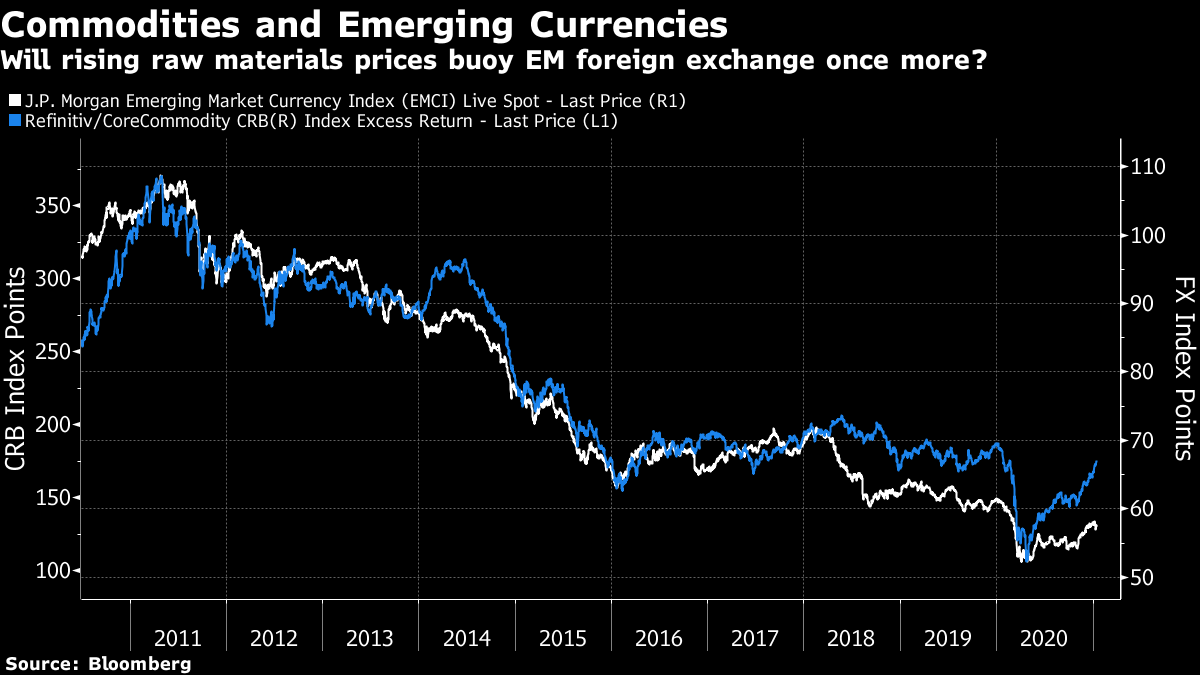

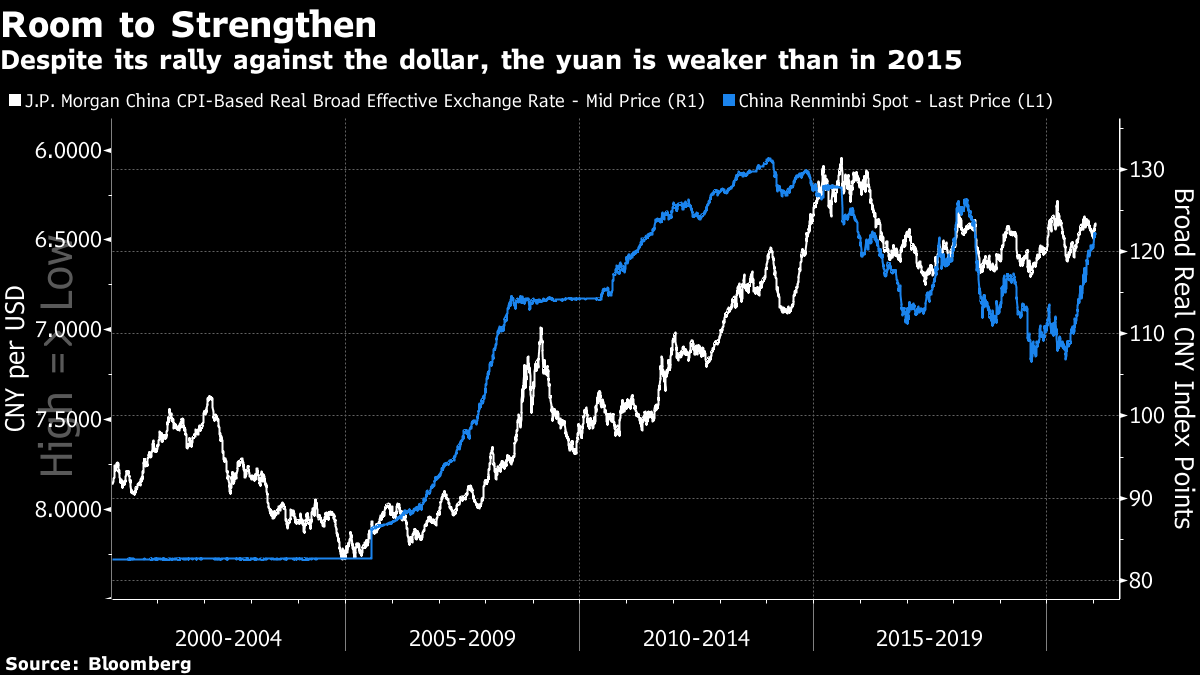

Rising Stars in the OrientWhile many of us find it impossible to avert our gaze from the political drama in Washington, D.C., the most significant market events may be happening far to the east. Back in 2007, Chinese mainland stocks suffered a burst bubble for the ages, as the authorities' attempts to micro-manage a stronger equity market backfired badly. There was another slightly smaller bubble in 2015, which ended when the indexing group MSCI disappointed expectations that it would start to include Chinese A-shares in its benchmark emerging market indexes (a process that has since started). And now the CSI-300 has at last exceeded that 2015 bubble, to hit a 12-year high:  Across the East China Sea, Japan is also at last making historic progress in recovering from a far greater bubble. Japanese stocks peaked on the last day of trading of 1989, and embarked on an epic crash. Three wasted decades later, the Nikkei 225 — Japan's best-known benchmark, has at last ascended to a 30-year high, touching a level not seen since 1990. True, the Topix, a broader and methodologically stronger index, still languishes some 35% below its peak back at the end of the 1980s, but the recovery of the last few years has still been impressive. Since the Bank of Japan embarked on yield curve control in 2016, the Nikkei has almost doubled. No surprise, then, that widely anticipated yield curve control from the Federal Reserve is expected to be equity-positive.  Why is this happening? Naturally, our old friend the coronavirus has much to do with it. The success of the northern Asian countries in limiting the damage from the virus while many others could not has attracted capital to their economies, and for good reasons. But some of that advantage should be wearing off now that the first vaccines have been approved and their distribution has begun. It is the emerging world outside China that has benefited most clearly from the advent of the vaccine; the following chart shows MSCI's index for emerging markets excluding China, relative to its developed world index. After a terrible 10 years in which the non-Chinese emerging markets lagged by some 40%, they have enjoyed quite a renaissance, particularly since Vaccine Monday in early November, when Pfizer Inc. first announced its positive trial results:  There could be much further to go. According to the Institute of International Finance, 2020 saw a net international outflow for non-China emerging market equities, while Chinese debt tended to hog inflows as investors looked for any opportunity to increase yield:  The most important flows in global capital markets come from central bank liquidity. China has been trying to rein its over-extended banking sector and seemed leery of pressing ahead with major expansions of liquidity. But shown by this chart from CrossBorder Capital Ltd. of London, which aggregates a number of different monetary mechanisms used by the People's Bank of China, it now looks as though the PBOC is hitting the accelerator again:  An expansionary China is great news for the countries most readily able to service its appetite — such as Japan, and South Korea and Taiwan, the strongest equity markets of 2020. It also helps the likes of Germany and Australia. Further, through expanding China's appetite for raw materials, extra money from the PBOC tends to mean higher commodity prices. As CrossBorder Capital shows, there is a relationship at work, and the scale of the liquidity now flowing in China should imply more gains for commodity prices ahead:  Those strong commodity prices should also have a helping hand from bullish traders. In futures markets, long positioning in a range of commodities is almost as strong as it has been in two decades, according to the following chart from Longview Economics of London. (The only time positioning was more bullish came in early 2018, in the wake of the U.S. corporate tax cut, amid the belief — soon disappointed — that the world was in the grip of a "synchronized recovery.")  As I commented yesterday, the revival of commodity prices has been very clear of late, and after a decade-long bear market there is plenty of room for them to appreciate further. This usually would be expected to buoy the currencies of emerging markets in turn. Strong commodities generally imply a weakening dollar, while much of the emerging world benefits from exporting raw materials. However, this isn't happening to the extent that might be expected — emerging market foreign exchange, as measured by JPMorgan Chase & Co., has strengthened against the dollar since the worst of last year's crisis, though not as sharply as commodity prices:  That implies further possibilities for emerging currencies, providing the commodity rally and the extension of liquidity by China continue. For this to happen, China's currency might again be a critical variable. It is easier for Beijing to let the liquidity flow without causing inflation if the currency is strengthening. Over the last few months the yuan has gained dramatically against the dollar, in a development that has helped to diminish global trade tensions somewhat. The intensely political nature of China's decisions on how to position its currency relative to the dollar can obscure the fact that the yuan remains tied to its U.S. counterpart, albeit to a lesser extent than used to be the case. While the dollar was strengthening, in the earlier part of the last decade, this meant that China grew steadily less competitive in real terms against a broad range of currencies. (Note that these calculations, from JPMorgan, involve consumer price inflation, while China may remain more competitive in terms of producer prices). The upshot is that the yuan remains weaker now, on this broad basis, than it was when it briefly prompted a minor global crisis with a sudden devaluation in August 2015. If China wants the currency to appreciate further, it could:  The U.S.-China relationship is the axis on which the world increasingly turns. That relationship is bound to remain difficult, even if the arrival of a new U.S. president next week could usher in significant changes. And tracking the PBOC makes Fed-watching seem easy. It is opaque by comparison, and uses many complicated instruments. Even so, the moves in commodity markets, and in Asian stock markets, suggest that Chinese liquidity is helping to drive trends that were set in motion by Asia's response to the coronavirus. It's nowhere near as dramatic as the excitement in Washington, but for the global economy it is probably more important. Survival TipsOn the subject of that heart-churning excitement in the Capitol, if you want to indulge your thirst to know more, I recommend Trivia Relief's special Treason, Coups and Other Assorted Villainy Quiz! I like Trivia Relief in any case, as it offers a fun way to give to often seriously strapped cultural organizations. Here are two tasters: The subtitle of this modern novel begins The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death. The work includes the following dictum, ascribed to a fictional author – "Americans, like human beings everywhere, believe many things that are obviously untrue."

and: In a March 2019 op-ed, Maureen Dowd referred to a prominent legal advisor as "Renfield…gratefully eating insects and doing the fiend's bidding." Provide the literary source of the character.

I've linked to the entire quiz above. You can find the questions plus answers here. There's also a presidential quiz. They should both be fun for all the family. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment