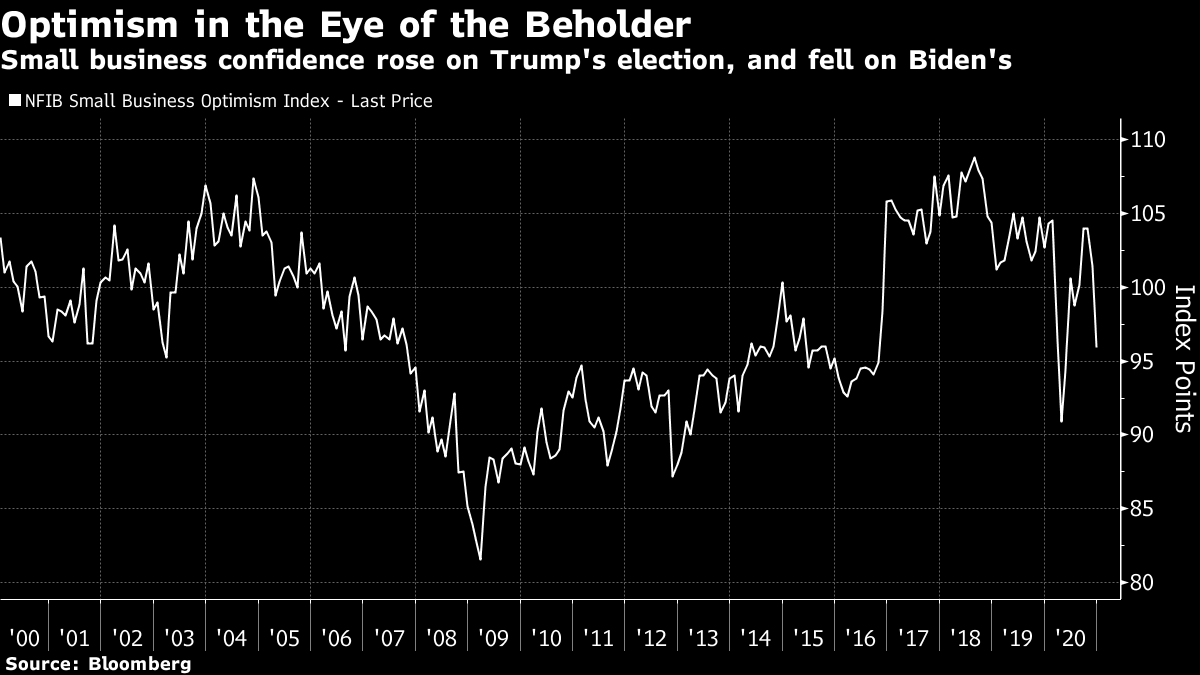

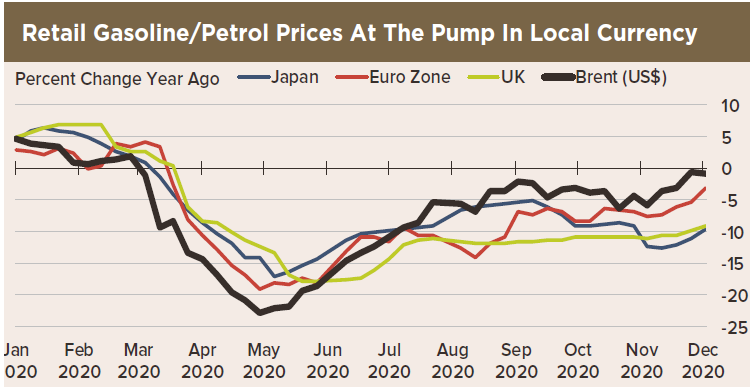

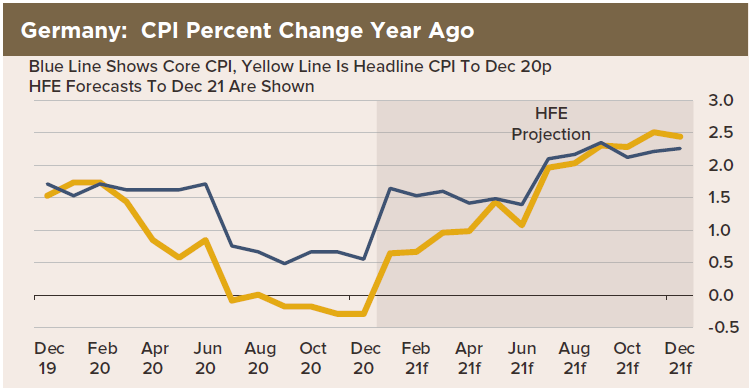

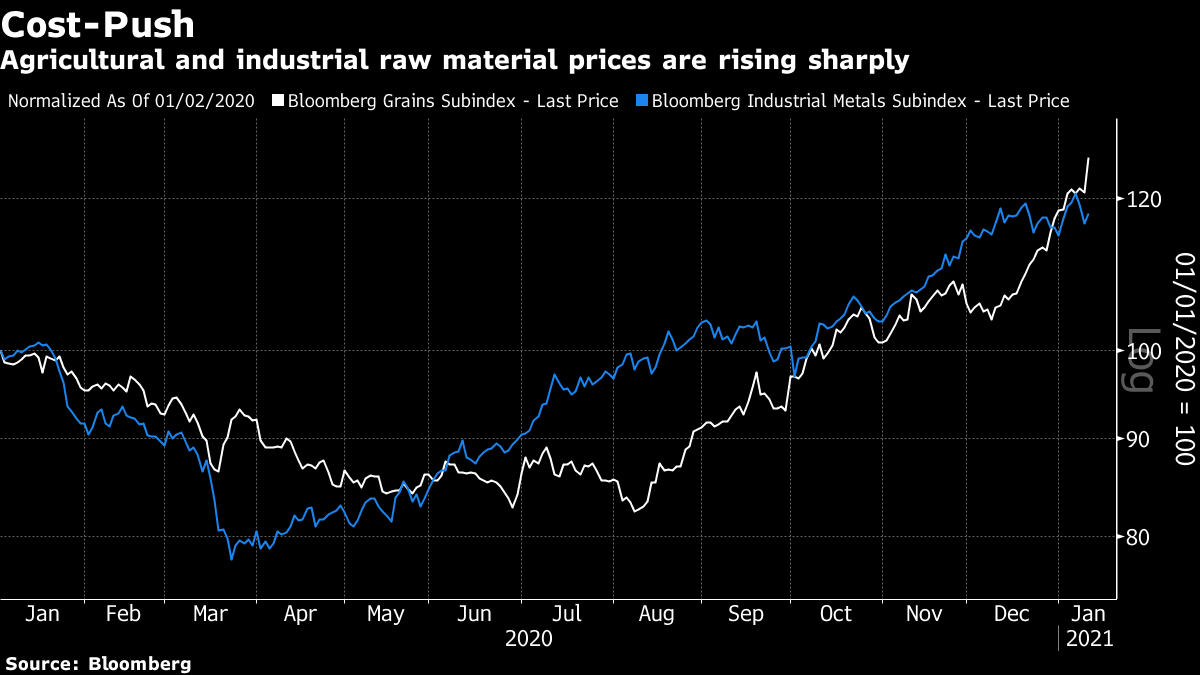

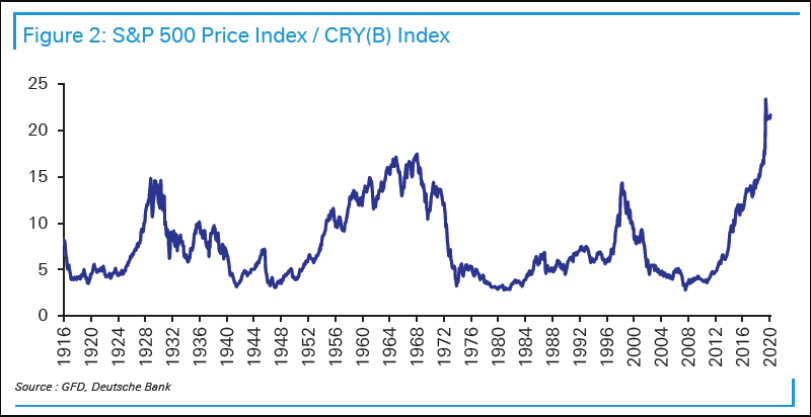

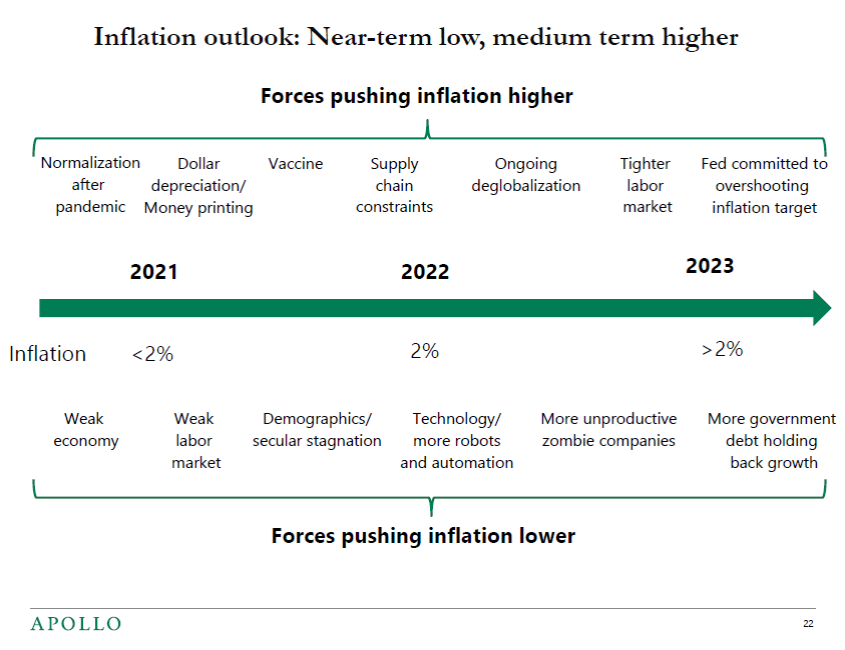

Lead Us Not Into InflationPrepare for a brief moment of truth, as Wednesday brings publication of the final U.S. inflation numbers for 2020. As I've said several times in recent weeks — because it bears repeating — a lot is riding on inflation staying quiescent. If it does, the outlook for asset prices looks set fair, as bond yields can stay at rock-bottom levels. If not, it doesn't take much of an adjustment for things to get ugly. Navigating these numbers is going to be difficult, thanks to the scrambled perceptions accompanying the pandemic. This is exacerbated by the growing tendency for political points of view to frame perception. For one intriguing example, look at the small business optimism index published by the U.S. National Federation of Independent Business on Tuesday:  Usually a good leading indicator, the index shows a sudden fall in confidence, far worse than had been expected, to the lowest level since the Covid-19 shock. But looking back at the previous two decades, note the low came just after Barack Obama had been elected, while by far the sharpest one-month jump came after Donald Trump won. This survey may tell us more about small business managers' low expectations of Joe Biden than it does about current conditions. Further perceptual problems are caused by base effects. The headline inflation numbers include gasoline bought at the pump. Crude's crash last March brought headline inflation down. Come spring, barring a remarkable new crash, base effects will push inflation upward. The following chart comes from a webinar by High Frequency Economics:  For another example of scrambled base effects, this time caused by policy, look to Germany. The government reduced VAT for six months, ended in December, to stimulate demand during the lockdown. This means much consumption and production will have been brought forward. Judging by comparisons with neighboring France, the tax cut had a big impact; according to High Frequency Economics' Carl Weinberg, French household consumption dropped 15% in November; in Germany, it rose by 1%. Consumption is likely to decline again and prices will jump back once the normal level of VAT returns. This doesn't necessarily mean the cut was a bad idea. But it could badly mess with perception. This is High Frequency Economics' projection for German core and headline inflation:  The end of the oil base effect will help headline inflation catch up earlier in the year, and then the end of the VAT base effect in the summer will cause both measures to rise together. There are other predictable price rises in the pipeline. Grains have enjoyed their sharpest increase in many years, while industrial metals are also rallying. Both fell during the worst of the pandemic, so again these increases stand to push headline inflation numbers up noticeably:  The revival of basic commodities raises another issue. They tend to move in long cycles lasting more than a decade — a phenomenon known as the Kondratieff Wave, in unlikely homage to Nikolai Kondratieff, a communist revolutionary economist who identified the waves, but met an untimely end when Stalin had him shot. Stock markets also tend to move in long bull and bear cycles, and it is notable that these overlap with Kondratieff waves. Bear cycles in commodities, as in the last decade, tend to overlap with good times for stocks. Good times for commodity prices, such as in the 1970s, tend to overlap with equity bear markets. This is logical — more expensive materials eat into corporate profits, push up inflation and divert resources that might otherwise have been spent on something more productive, or on equities. When stock markets have been rising for a long time, it also shouldn't be surprising that demand for raw materials is strong. If this relationship is as significant as it seems, that implies worrying things for the equity market. This following chart, from Jim Reid of Deutsche Bank AG, shows the ratio between the S&P 500 (excluding dividends) and the Refinitiv/CoreCommodity CRB (R) index going back to 1916. When denominated in terms of raw materials prices, the S&P 500 has never looked more expensive. A reversal looks like a real risk:  There are any number of reasons, then, why inflation will be noisy in the year ahead. All of this said, a basic point remains hard to overcome: The labor market is still generating no inflationary pressure to speak of. Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management in New York, produced this somewhat intimidating graphic with all the pressures upward and downward on inflation:  However, Slok also provided a succinct summary on why optimism for controlled inflation remains strong: The key argument why inflation will not be a problem for several years is that when the unemployment rate was 3.5% in February, we did not see any signs of inflation, and according to the latest FOMC forecast, it will take at least three years before we reach that level again. I doubt that any of the pandemic-related factors in the chart will be big enough to change this simple forecast.

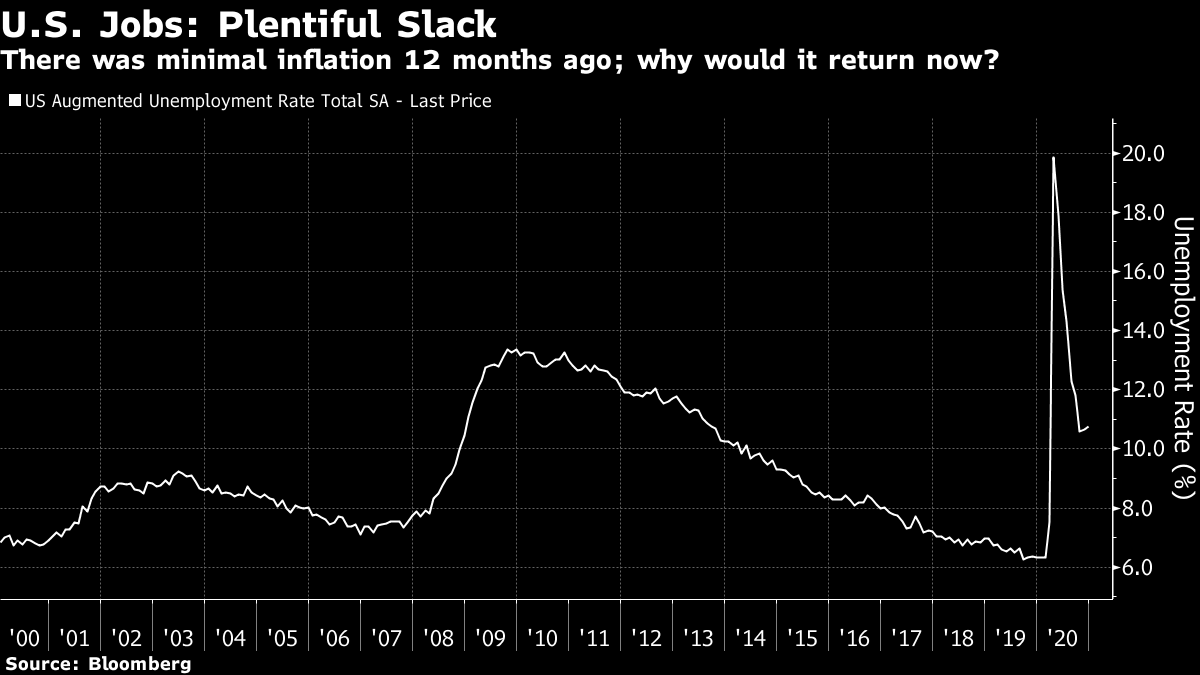

Since he wrote that, the U.S. unemployment numbers have stalled, in the face of renewed disruption from the pandemic. Using a broad measure that includes those who might be able to work but aren't actively seeking employment, the jobless rate is more than 10%. This is more than double the rate a year ago, and inflation was supine then:  The weak employment market is likely to limit the current rebound in inflation expectations. But there will be so much noise in year-on-year comparisons over the next 12 months that a renewed inflation scare in the bond market could still easily happen. Family ValuesValue investing has had a miserable decade, and a terrible last year or so. Value investors, who look for stocks that are cheap compared to their fundamentals, have lost brutally to growth investors, who hunt out companies that are expanding rapidly. Or maybe the dichotomy is being overstated, and we are measuring it wrong. The legendary investor Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital Management published a new memo this week. It's long, and worth your time. Marks structures the note as a conversation with his son Andrew, with whom he has been sharing the inconveniences of the last year. The younger Marks specializes in large tech companies and is distinctly a "growth" investor; Marks the Elder made his fortune investing in credit, which involves working out the underlying value and creditworthiness of a company — very much skills that make him a "value" investor. After months of discussion, the Marks family has come up with a way to ease the contradiction between growth and value. One of the most interesting points concerns benchmarks. Indexes labeled "value" might be more caricatures of portfolios that value investors would ever actually put together. Marks says: It's interesting to note that the methodology for populating the S&P 500 Value Index relies solely on finding the one-third of the S&P 500's market capitalization with the highest ratio of Value Rank (based on the lowest average multiple of earnings, sales and book value) to Growth Rank (based on the highest three-year growth in sales and earnings and 12-month price change). In other words, the stocks in the Value Index are those that are most characterized by "low-valuation parameters" and least characterized by "growth." But "carrying low valuation parameters" is far from synonymous with "underpriced." It's easy to be seduced by the former, but a stock with a low p/e ratio, for example, is likely to be a bargain only if its current earnings and recent earnings growth are indicative of the future.

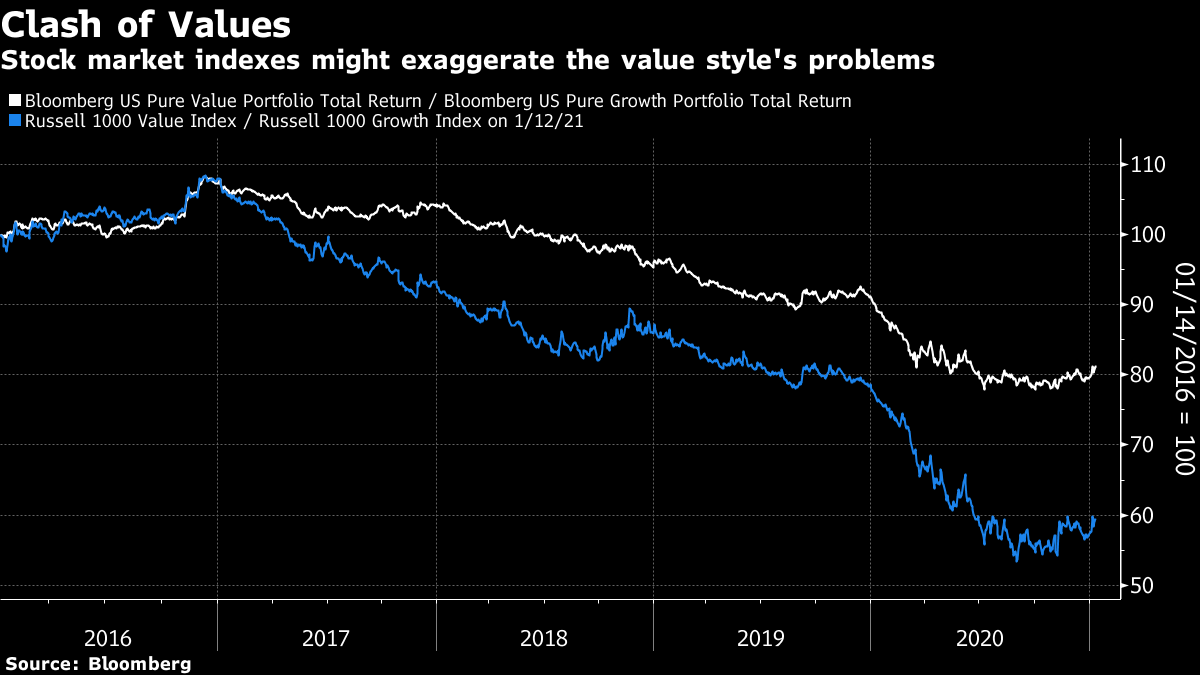

Benjamin Graham, the founder of value investing, famously wanted a "margin of safety." The idea was that a stock's underlying value should be high enough that even if the worst came to the worst, he would be OK. He also wanted to find companies that would grow a lot, providing he didn't have to pay for them. Value indexes, by excluding cheap companies that also have growth characteristics, may avoid exactly those that he might find most interesting. The following chart compares Bloomberg's measure of the pure value return relative to the growth return and the performance of the Russell 1000 Value index compared to the Russell 1000 Growth index. Both show the same trends. Value has definitely lagged growth over the last decade; but the indexes exaggerate the effect:  The evolution of value investing is well known. Buffett was taught by Graham at Columbia Business School, and always used his methods — but expanded over the years into looking for strong companies with well-defended competitive advantages (or "economic moats"). That led him to take long-term stakes in companies like Coca-Cola Co. or Gillette Co. Professor Bruce Greenwald, who teaches the current iteration of the value investing class that Graham started, includes "franchise value" in calculations of a company's underlying worth, factoring in its ability to generate future cash flows. The more recent Buffett approach could almost be labeled "growth" as easily as "value." That gives Marks this epiphany: The two approaches – value and growth – have divided the investment world for the last fifty years. They've become not only schools of investing thought, but also labels used to differentiate products, managers and organizations... My belief, especially after some deep reflection over the past year – prompted by my conversations with Andrew – is that the two should never have been viewed as mutually exclusive to begin with.

Personally, I suspect much of the contemporary view of growth versus value stems from the commercial imperatives of fund managers and advisers. Presenting funds as being either "value," "growth" or "core" makes investing look a bit more complicated, encourages more shifting between funds, and helps asset managers to market them. One more important point: The opportunity to make money in the way Graham laid out in the 1930s may have dwindled to nothing. This may, I'm afraid, be partly Bloomberg's fault. Information is just too easy to obtain these days. In the 1930s, or when Buffett was starting out in the 1960s, there were huge returns for those prepared to put in the work: When Buffett was applying his cigar butt approach to running his early investment partnership – which racked up a tremendous record – he famously used to sit in his back room in Omaha, flipping through the thousands of pages of Moody's Manual, and he would buy shares in small companies that were trading at enormous discounts from liquidation value for the simple reason that no one else paid attention to them. In one case, that of National American Fire Insurance, Buffett was able to buy the stock at 1x earnings by driving around to farmers who had decades earlier been stuffed by promoters with stock they'd since forgotten about, and handing them cash on their front porch. Thus, the Grahamian value framework was created at a time when things could be stupidly cheap based on clearly observable facts, simply because the search process was very difficult and opaque.

So maybe Bloomberg killed the value investor, just as video once killed the radio star. Sorry about that. Survival TipsVideo Killed the Radio Star makes me think about one-hit wonders. The Buggles didn't go on to a great career. However, Trevor Horn, the lead singer, turned into the maestro go-to producer of his generation. You could try Owner of a Lonely Heart by Yes (sounding very different from their earlier incarnation), or Two Tribes or Relax by Frankie Goes to Hollywood (produced and more or less performed entirely by Horn); something from his oeuvre with Art of Noise, such as Moments in Love (a song fit to be performed in the British Library) Close to the Edit or Kiss; All of My Heart by ABC; or Crazy by Seal. As for other true one-hit wonders of my generation, maybe try The Passions, or Nena, or The Vapors, or Martha and the Muffins. Add more to taste. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment