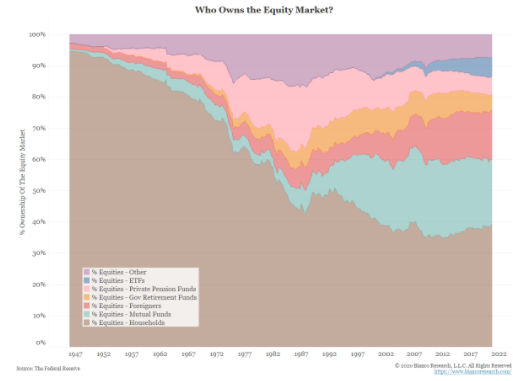

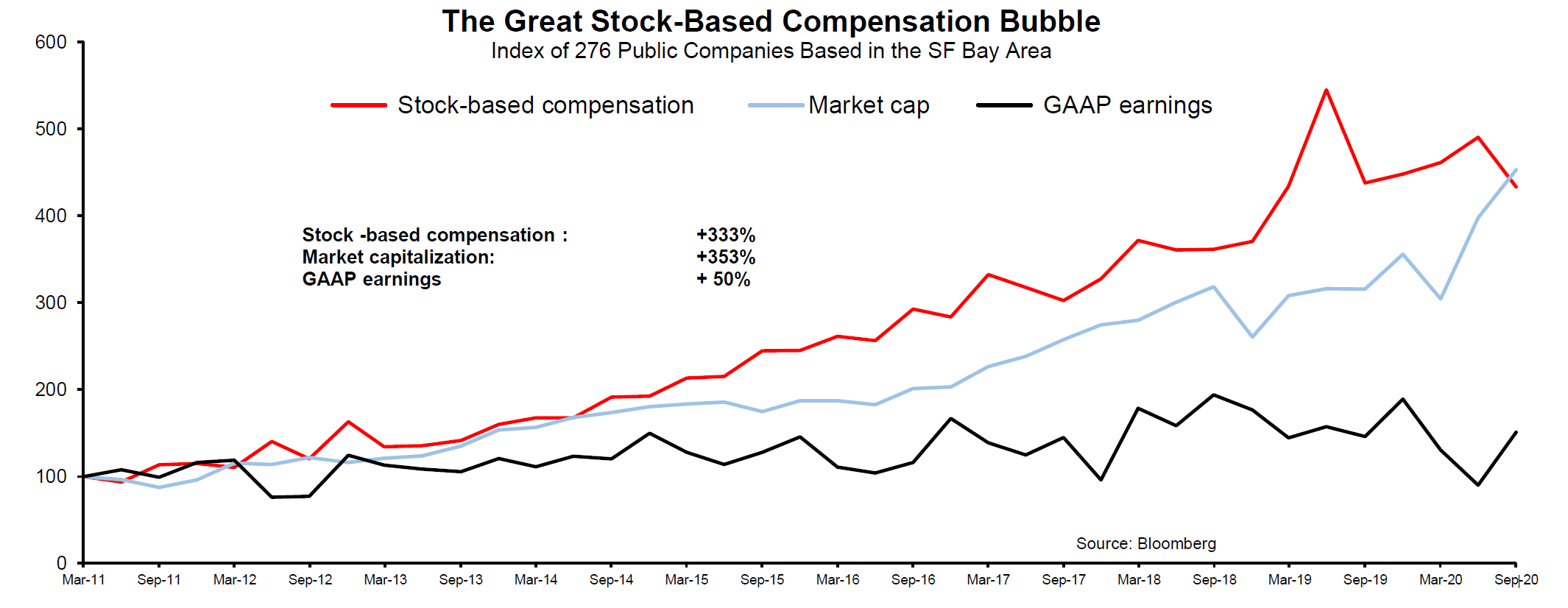

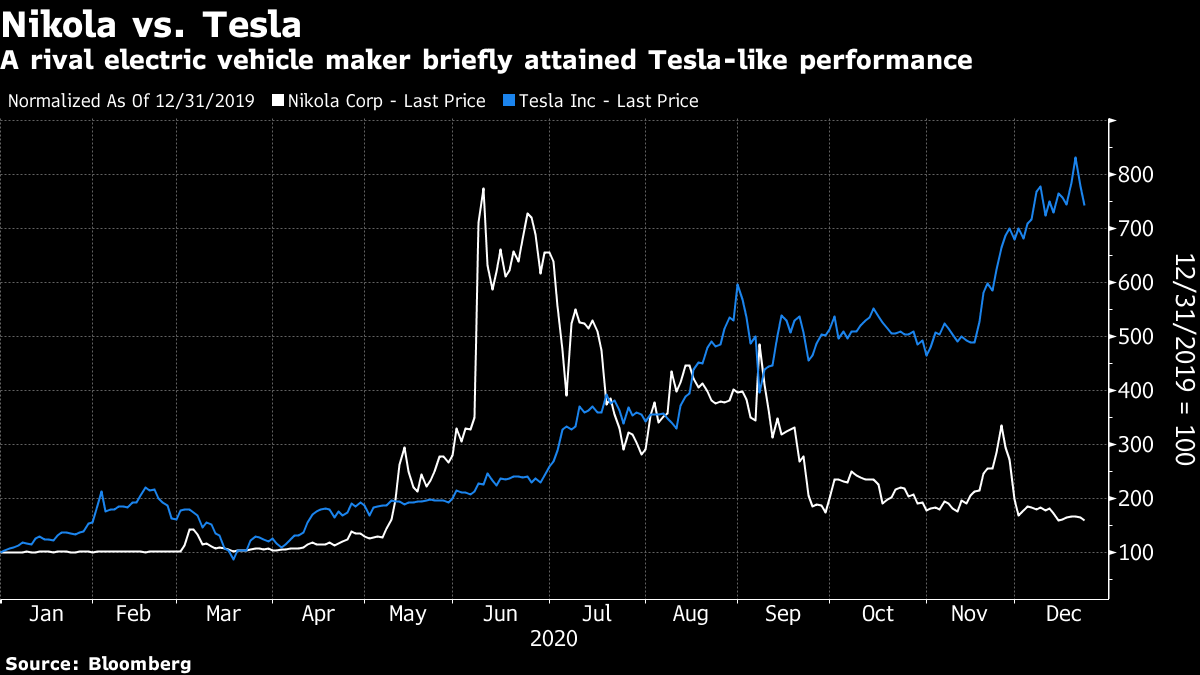

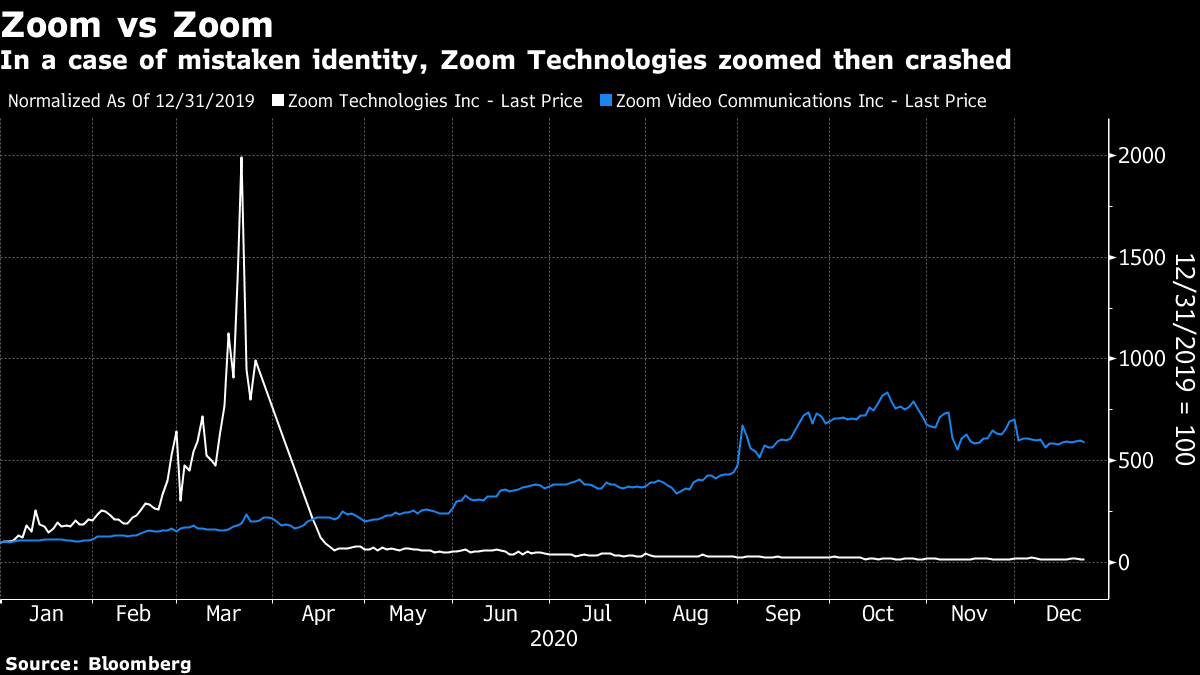

Institutionalized, Professionalized, Democratized or Gamified?I mentioned earlier this week that markets have grown far more institutionalized over the last half-century. Some would object that the word is pejorative and say that they have been "professionalized." Either way, the idea is the same. Emerging from World War II, prices on the U.S. stock market were set by trading between people buying and selling shares that they owned, for their own account. This changed with the great post-war growth of pension funds. By the turn of the millennium, the power of individuals over the stock market was much reduced, and trading was largely a game for different institutions handling other people's money. The change introduced the classic division between principals and agents to the stock market. Institutions may often have different interests than their clients. Generally, they are paid for accumulating assets, not for making the most money with them. This tends to foster herding and groupthink. Make sure that your choices are much the same as everyone else's and there is little risk that someone else will strongly outdo you. Thus, you can hold on to your money. Institutionalization has had other effects. As more money is controlled by people investing at scale, with access to high-powered trading technology and lots of research at their finger tips, it grows harder for little guys trading on their own account to fight back. You begin to see what Charley Ellis famously called the "Loser's Game" — the less skillful are squeezed out and the game of investment management becomes a contest with an ever more talented and well-resourced group of survivors. Continuing to win grows ever harder. Meanwhile, the growth of institutionalization means there are fewer people trading their own book, or who hold shares for their own reasons (such as families still holding on to hereditary stakes in the ancestral business), and therefore fewer people who are not motivated to "win" by generating the greatest return. That makes it harder to generate a win in what is ever more a zero-sum game, and inspires institutions to resort to indexing, which effectively amplifies the power of groupthink still further. These trends have had an air of inevitability about them for a while. A decade ago, when I wrote a book about the causes of the 2008 crisis, I argued that the institutionalization of the stock market and the steady introduction of the split between principals and agents was one of the prime causes. I return to it now because Bloomberg Opinion colleague James Bianco provided an update of the Federal Reserve's chart of the ownership of the stock market in his latest newsletter. It shows that the great decline in equity ownership by households halted at the turn of the century. Since then, it has risen very slightly. The biggest changes in the current century have been the rise of exchange-traded funds and of foreign holdings, at the expense of mutual funds and private pension funds:  Why has the proportion of the stock market held by individuals started to rise again? And what effects could it have? A look at the contributing factors may help shed some light. Stock-based Compensation The strongest explanation, I suspect, for this shift in stock holdings is an outgrowth of the "wealth effect." The last 20 years have created wealth in some concentrated areas, and founders and CEOs are holding on to a greater share of their companies. Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg alone do much to increase the amount of stocks held in individual hands. Many companies, particularly in Silicon Valley, are rewarding more of their employees with equity. Provided that the stock market keeps rising, this is cheaper for the company and more lucrative for the employee, so everyone wins — and the percentage of shares held by individuals tends to rise. Vincent Deluard, investment strategist at StoneX, recently published this chart to give an idea of the impact of stock compensation in the Bay Area. The numbers are extraordinary, and suggest a net transfer of wealth to already-wealthy individuals:  Retail trading Beyond stock compensation, there is the growing popularity of retail investing. Precise numbers are annoyingly difficult to obtain, but 2020 looks to have had the greatest explosion in individuals trading for their own account since at least the closing days of the dot-com bubble. With Robinhood, the best-known discount trading service, reaching 13 million users this year, small traders are beginning to have an effect. Crucially, unlike the likes of Bezos or Zuckerberg, Robinhooders are not holding stocks for the long term, but trading heavily. Traditionally, we could assume that the stocks held by households for their own account would be traded far less actively; company founders and their families tend to have a commitment to a specific company, for example. That assumption may no longer be so good. The impact of Robinhood has been felt in a number of ways. Critically, it turned out earlier in the year that they were more willing to buy the dip during the March market implosion than their counterparts at big institutions. Research I covered at the time showed there was an almost linear relationship between the proportion of institutional ownership of a stock and its likelihood to be sold during the March selloff. Robinhooders not only bought during the frightening period, but they were also prepared to buy extremely risky stuff, with a particular liking for companies that had weak balance sheets. This is a heart-warming story. The little guys kept their nerve and beat the institutions during the slump, repeating a pattern that was also seen during several of the market selloffs during the closing years of the 1990s bull market. Thus did some of the wealth created by the Federal Reserve's Covid-19 rescue efforts end up in the pockets of little guys. But there was also disquieting evidence that the retail money was not that smart. Exhibit A is the remarkable performance of Nikola Inc., which makes electric trucks. It endured a boom and bust during the year as it made some great claims for progress that then came under withering fire:  Had small investors really checked it out? Then there was the extraordinary story of the tiny Chinese company Zoom Technologies, which as the year opened had the ticker symbol "ZOOM." As lockdowns took hold and everyone started to use the services of Zoom Video Communications (ticker: ZM), there was a massive spike in Zoom Technologies, followed by a crash. Regulators also required it to change its ticker symbol to avoid confusion, but by then the damage was done:  Incidents like this add to the worrying sense that the growth of individual trading is a symptom of top-of-market froth (just as it was two decades ago), and that the end result will be a lot of little guys bearing the brunt of losses in any new downturn. To add to the sense of unease, Robinhood — which hopes to IPO next year — has been in trouble with regulators. Last week it agreed to pay a $65 million fine to the Securities and Exchange Commission over its failure to alert clients that it was selling their trading information to high-frequency traders, a practice that persistently diminished clients' returns. It also faces legal action in Massachusetts from securities regulators who say Robinhood is unduly aggressive in its marketing and turning markets into a game. Which leads me to ... Gamification? The Robinhood app makes it easy to trade and has the trappings of many of the online games that kids find addictive. But is it really fair to accuse it of "gamification?" Bloomberg Quicktake offers a summary of the arguments and points out that gamifying might help to encourage more investment, which would be a good thing. Robinhood could be seen to be doing its bit to do away with the damaging principal-agent split in the ownership of the stock market. Meanwhile, Bloomberg Opinion contributor Aaron Brown (formerly of AQR Capital Management) made a trenchant argument that Robinhood was democratizing markets, not gamifying them. This is how he covered two specific charges in the Massachusetts complaint: The first is that "Robinhood uses gamification strategies in order to lure customers into consistent participation and long-term engagement with its trading platform." Older readers may remember that early on-line brokers like TD Ameritrade and E*Trade were accused of offering "Nintendo trading" for having user-friendly interfaces. Although "gamification" is used throughout the Massachusetts complaint and press release, the only example is confetti raining down on the app when a Robinhood user completes trades. I agree that's not appropriate, but it hardly supports a general charge of gamification. And again, why the use of the word "lure"? Every company uses strategies to attract and retain customers. Second, the complaint provides 25 examples of Robinhood customers trading from 15 to 92 times per day, but no other information or context is provided. Someone investing $500 per month in S&P 500 Index stocks could easily execute 25 trades per day on the Robinhood app without drawing concern given there are no commissions, one has the ability to buy fractional shares and that the firm's minimum trade size is $1. Looked at another way, someone day trading $1 could be gaining valuable investment experience without risking significant cash.

I take his point, but fear that he is being too kind to Robinhood. Their biggest news since they settled with the SEC is that they are cutting interest on margin loans from 5% to 2.5%. They are halving the price of going into debt to put money at risk in the stock market. This is the graphic I found on the company's tweet to announce this important development:  Personally, I think this strays into unacceptable "gamification." Robinhood is training people to trade, rather than to invest, using some of the techniques of a game to do so. Trading has a lot of the attributes of a game, and those who are good at it enjoy it a lot. But amateur traders who aren't so good and lose their money don't enjoy it one little bit. I met plenty of such people during my time as a personal finance journalist, which may skew my judgment. In the long run, even with minimal commissions, rigorous academic studies show that it's mighty difficult for day traders to beat the market. And it's virtually impossible for someone doing it as a hobby, who also has a day job, to beat the professionals on a long-term basis. Those who get addicted to investing — and it can easily happen — can lose money they cannot afford to lose. ETFs Meanwhile, there are also problems with the growth of ETFs, the single greatest change in stock market ownership of the last two decades. ETFs can also be seen as "democratizing" in a way — they allow investors make their own asset allocation decisions with ease, and make a range of strategies far more accessible. But they can also be seen to hasten the problem of the split between principals and agents, vesting ever greater power in those who compile indexes. And the ETF structure, by enabling individuals to trade whole asset classes minute by minute throughout the day, also "lures" (to use the word that Brown finds contentious) people into possibly excessive trading behavior. The return of retail investing and the rise of the ETFs both genuinely help to democratize the market, then. But both also tend to encourage excessive trading, which ultimately most benefits the institutions who now enjoy the greatest power over the market. Democratization matters, and it's important to try to achieve it, but these are not the best ways to do it. If the test cases around Robinhood help produce some ground rules for encouraging people into the stock market, that would be a good result indeed. Survival TipsI started this section nine months ago, thinking it might be fun. I didn't think I would still be writing them now, but it looks as though the worst few weeks of the pandemic, for many of us, are about to happen. It has been fun to find out which tips provoke a response, and to discover all kinds of things I would never have guessed about the musical taste of Bloomberg's clients. The crowd-sourced tips from readers have also been fascinating, and have produced plenty of gems. Tomorrow's Points of Return will be the last regular newsletter of the year (barring a special between Christmas and New Year). If any of you out there have any particular tips you'd like to share with other readers to help get through what could be a very difficult holiday season, please share them with me (at my personal email address rather than by pressing reply to the email version of this newsletter), and I'll see if I can put together a bumper crowd-sourced version to end the year. Meanwhile, my recommendation for the single best rowdy song to keep you awake and give you a jolt when you are running on fumes at the end of a long and tiring year is this little-known gem.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment