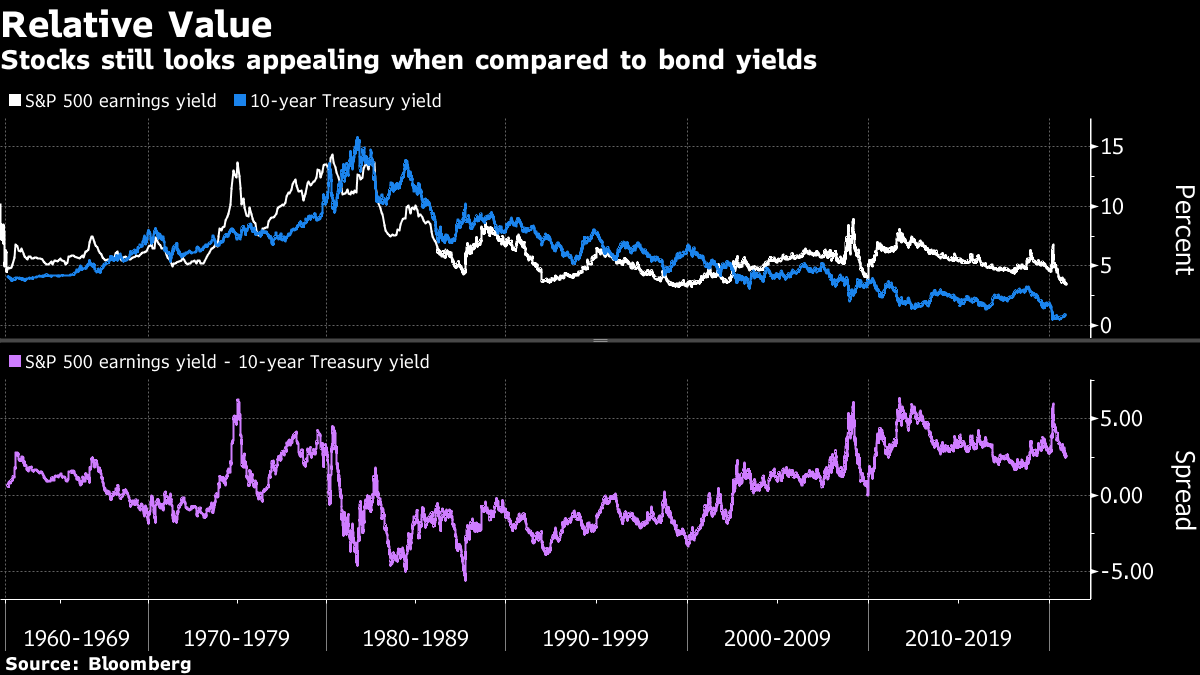

| Welcome to The Weekly Fix, the newsletter that isn't written on cocktail napkins or toilet paper. I'm cross-asset reporter Katherine Greifeld, filling in for Emily Barrett. Uncomfortable or Coy?Chairman Jerome Powell refused to be boxed in during the Federal Reserve's last policy meeting of 2020. The statement had a similar tone to those over the past few months: the economy is improving, but the next few months will be challenging. The majority of Fed officials see rates near zero at least through 2023. Inflation remains well below target. But naturally, it was the future of the Fed's asset purchasing program that got bond markets buzzing. Policy makers voted to maintain bond buying of at least $120 billion per month until they see " substantial further progress" in employment and inflation, scrapping the previous pledge to continue purchases "over coming months." But as for what qualifies as "substantial," Powell was coy. He told reporters at the press conference that he "can't give you an exact set of numbers," but that the economy was "some ways off" from reaching that point. To Grant Thornton's Diane Swonk, Powell's demurring was masking deep divisions among committee members about how the central bank will gracefully disentangle itself from bond markets.  "It was the least possible guidance the Fed could offer in terms of asset purchases going forward. The Fed doesn't know how it's going to extricate itself from these purchases going forward," said Swonk, Grant Thornton's chief economist, in a Bloomberg TV interview. "You really saw the Fed chairman be extremely uncomfortable talking about that." Others disagree. Powell's performance was one of a Fed chair simply trying to maintain optionality and avoid getting "painted in a corner," according to Hirtle Callaghan & Co.'s Mark Hamilton. Rather than assign a numerical target for the unemployment rate or inflation readings and have markets fixate on the possibility that the Fed would scale back asset purchases when approaching that figure, being deliberately vague preserves flexibility for policy makers -- and protects against the kind of market wobble seen in 2013. "Think about the taper tantrum that they inadvertently triggered -- they don't want to do that," said Hamilton. "What they're trying to do is remind everybody that there's a very deep hole there and we're going to give the economy plenty of time to dig itself out, so we're not going to focus on an end date or conditions for an end date." Also of note: there was no change to the composition of their asset buying, and policy makers declined to shift purchases toward the long-end of the curve. It was far from consensus that they'd venture out the curve, but there was some degree of speculation that they'd unveil some form of forward guidance along those lines.  But although it's abundantly clear the U.S. labor market recovery has stalled and November retail sales were particularly ugly, the economy hasn't deteriorated to the point where the Fed would need to pull the trigger. "Financial conditions are extraordinarily easy," said Mark Cabana, head of U.S. rates strategy at Bank of America, in a Bloomberg TV interview. There's no reason for the Fed to take additional easing measures "when you've got equities at or near all time high, mortgage rates at or near lows, credit tight and flowing." Don't Sweat Stock ValuationsBut in maybe the most stunning moment from the press conference, Powell broke out a version of the so-called Fed model, which compares the S&P 500's earnings yield to bonds. Powell posited that because risk-free rates of return are so low, stocks -- which may look screamingly overvalued by some measures -- perhaps aren't as expensive as they appear. "Admittedly P/Es are high, but that's maybe not as relevant in a world where we think the 10-year Treasury is going to be lower than it's been historically from a return perspective," Powell said. The Fed model is often cited by equity strategists and economists to justify lofty equity valuations. It's not too often that a Fed chair engages in that exercise.  Currently, the S&P 500's earnings yield -- profit relative to share price -- is about 2.5 percentage points higher than benchmark Treasury yields, implying that stocks are attractive relative to bonds. At the height of the dot-com bubble of the late 1990's, the measure fell below -3 percentage points as 10-year Treasury yields flirted with 7%. Currently, they clock in at around 0.92%. Citing the Fed model isn't necessarily misguided, but it's by no means a reason to be bullish on stocks, according to Richard Bernstein Advisors's Dan Suzuki. Rather, it suggests that anemic bond returns could make so-so equity gains look appealing in comparison. "Rates are low, partially because growth has been weak -- hardly bullish. I think there's significant risk that rates move higher over the next several years, which based on Powell's logic should argue for incrementally lower valuations -- also not bullish," said Suzuki, the firm's deputy chief investment officer. "What the Fed model is telling you is that those modest equity returns could turn out to be great relative to the returns you get from bonds." Riding a Junk Frenzy It was another monster week of junk bond issuance, putting this month on track to be the busiest December since at least 2006 in the high-yield market. With junk borrowing costs at record lows, it's hard to resist. But in a sign of just how red-hot high-yield has become, the companies most-battered by the pandemic are leading the charge. Norwegian Cruise Lines Holdings Ltd. was among the rush, borrowing on an unsecured basis -- no cruise ships or other valuable assets pledged as collateral. Amazingly, the company targeted a yield of around 6.75% -- roughly half the 12.575% it had to pay in May on a secured debt sale. "We're in this unique position with a lot of fallen angels in very challenging industries due to Covid -- like the cruisers and airlines -- that are accessing capital markets just in case," said John McClain, a portfolio manager at Diamond Hill Capital Management Inc. "It's kind of a rainy day fund." Such issues have been met with hearty demand, and for good reason. An index tracking U.S. fallen angels -- debt rated investment grade that have been downgraded to junk -- has surged roughly 43% since March's low. Meanwhile, record amounts of cash have poured into exchange-traded funds tracking such securities.  A natural byproduct of such froth is renewed concerns over protections investors are receiving in debt deals -- particularly in junk markets, where companies tend to be highly levered and credit quality is a more "immediate" concern, Hamilton said. He's been avoiding high-yield in favor of investment-grade bonds and higher quality equities. "An investor wants input over how much flexibility does this company have and make sure they're not able to deteriorate the quality of the credit," Hamilton said. "When you get into a market where terms are pretty easy -- either people aren't demanding covenants or they aren't willing to grant them -- you end up with something where you've less protection underneath you," Hamilton said. Of course, covenants concerns aren't a new phenomenon, and creditor protections have long been a sticking point between lenders and issuers. But though covenant quality has been eroding for years, that trend has been exacerbated in some ways by a tumultuous 2020. Those brawls took on greater urgency during the summer months, and increasingly, more high-yield and leveraged loan deals are 'covenant-lite' and include scant safeguards. The solution for Diamond Hill's McClain has been to avoid debt deals where covenants "will be used against us," as borrowers almost always have the upper hand. "Covenants used to be written on cocktail napkins, and now they're scribbled on toilet paper in crayon," McClain said. "Issuers are 95% of the time in a stronger position than lenders because they pick when they come to market." Bonus Points - Up Against Wall Street Bond Giants, Minority Firms Want More

- The work-from-home boom is here to stay, but pay cuts are on the way

- Robinhood Markets will pay a $65 million fine to settle a probe into whether it properly informed clients it sold their stock orders

|

Post a Comment