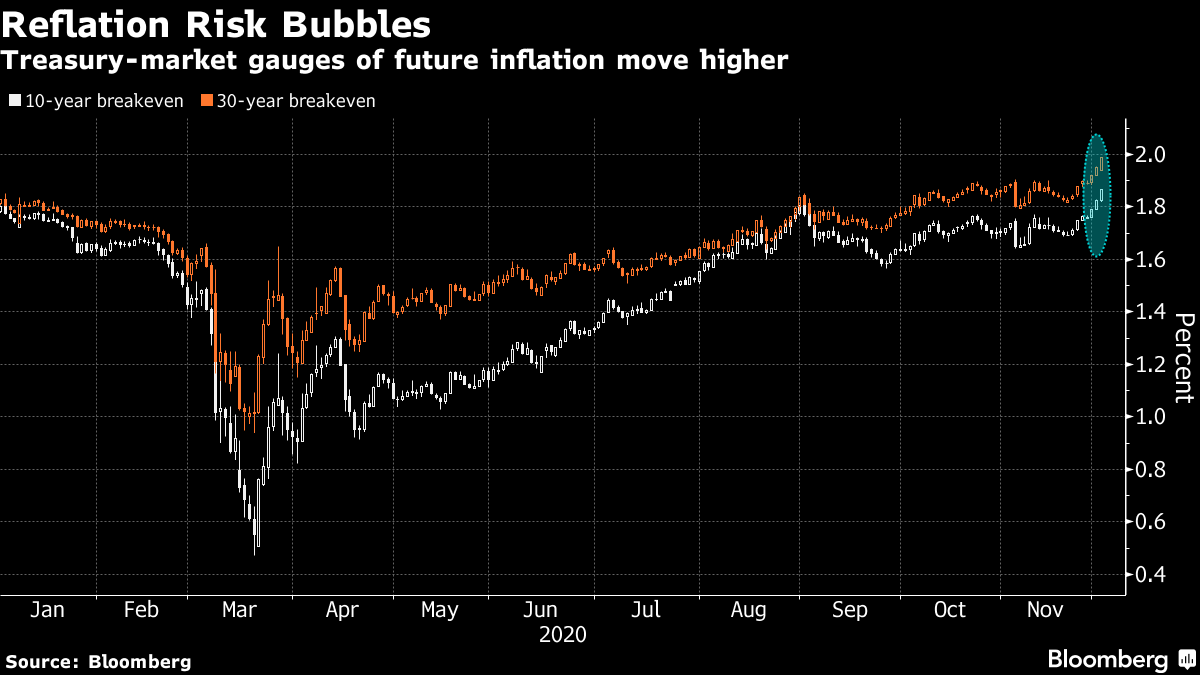

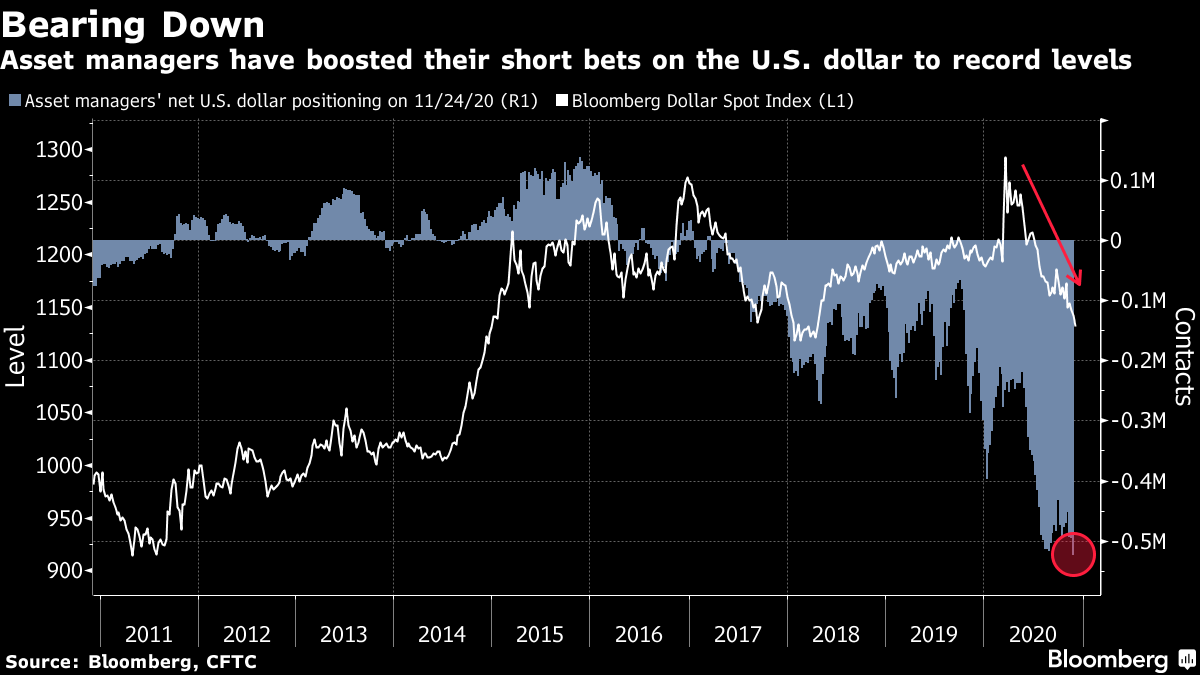

| Welcome to The Weekly Fix, the newsletter that bids farewell to our robot overlords at roughly 1.01% -- Emily Barrett, Asia FX/rates editor. Better days... and not-so-golden yearsWe'll indulge a few moments of looking through the myriad uncertainties of today, to the Street's vision of the not-too-distant future. Our inboxes are bursting with outlooks, and pretty much all of them envisage a world transformed. "The market is gradually pricing a positive scenario for the real economy next year, which we cannot afford to miss." Bank of America's strategists clearly don't believe in such a thing as jinxing yourself. That sentiment underpins their top trades for 2021, which are bursting with reflation bets -- buying short-end TIPS, selling the dollar and the 30-year Treasury bond. (It's forming a double bottom. Well who isn't, with all this sitting around.) We've started to have glimpses of this world, which turns on the promise of widespread vaccinations and a substantial U.S. pandemic relief bill. While the stock market is lapping it up, true to form the bond market is reserving judgement, with the U.S. 10-year yield still wavering on the brink of 1%.  A 1% rate on the global bond benchmark has strong symbolism across asset classes. Investors this week associated it with further gains across emerging markets and global stocks -- the MSCI ACWI has been setting record highs since the U.S. election -- on the assumption that the rise is measured and matches the pace of a gradual recovery. Alternatively, there's this slightly more alarming take from quant-land, which predicts a robot mass-exodus from Treasuries if we get to 1.02%. And it could be third-time lucky for the 10-year to push decisively above this threshold, as buyers in Asia have seemed less keen lately to pounce on any weakness in U.S. government bonds. The contours of a classic pro-growth and pro-inflation market are more broadly discernible. Long-dated yields have risen above the short end, with the curve between the two- to 10-year notes hitting its steepest since October 2017 this week. And 10-year breakevens -- the market-implied measure of the inflation rate over the next decade -- have risen to their highest point in more than 18 months. That has Bill Dudley -- former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York -- worried about inflation coming back "much more quickly than the consensus suggests.''  The reflation trade probably has some stamina, according to BMO Capital Markets' Ian Lyngen. The rise in breakevens isn't vulnerable to the potential for more Fed action, since a further commitment to extending the maturities of its Treasury purchases at the Dec. 15-16 meeting could fuel inflation expectations, and quickly curb any further rise in long-end rates. "We're onboard with investors' budding expectations to see a fresh round of consumer price pressures as the vaccines have now provided a path toward reopening and rebuilding the global economy," Lyngen notes. Even more popular in the reflation handbook is the short dollar trade, which continues to flourish, as reported by our currencies mavens Ruth Carson and Hooyeon Kim. The greenback sank to multi-year lows against several of its riskier peers this week, as asset managers extended their short positions to record levels.  One angle that hasn't got much play in the big 2021-recovery narrative is the cost of the massive central bank effort to engineer it, as real yields sink further below zero. John Authers delved into the slow-moving crisis that we'd all prefer to ignore (alongside climate change) -- with an examination of how this year's historic bond-market rallies are crushing our retirement savings. For further depressing evidence of the desperation that's gripping pension-fund managers worldwide, check out the website of the world's largest. This week, Japan's monolithic Government Pension Investment Fund posted a request for "information and ideas" on its website (hat tip to our own Stephen Spratt, who spotted it): "While zero interest rates were at first considered a temporary measure, twenty years have passed since they were first introduced, and even long-term interest rates have been kept around zero since 2016 under the BOJ's yield curve control policy. Now with the emergence of the first global pandemic in over 100 years, the Federal Reserve Board revived its own zero-interest rate policy in March of this year for the first time since December 2015, and the US long-term yield also dropped below 1% for the first time in history." "In light of this, GPIF is requesting information on the mechanism that has generated and entrenched this global zero-interest rate environment, and for ideas on a way to estimate expected return for domestic and foreign bonds in the midst of such an environment."

Or, otherwise translated: For the love of God please make it stop. For all our sakes. Plans to make it stop.We talked last week about how the Fed might be keen to delineate an exit strategy in light of the latest positive developments on a vaccine. We'll see from Friday's jobs numbers how much urgency the economic recovery is likely to add to those endeavors. But even as the global economy -- and certainly most of the people living in it -- struggle through what's still a worsening pandemic, some interesting views are coming to light about how the market is likely to behave in a recovery, and how central banks will respond. In a nerdily gripping interview on the Odd Lots podcast this week, former European Central Bank Chief Economist Peter Praet said he is "worried about the normalization phase." "At some point we have to be prepared because there is light at the end of the tunnel and the train might be faster than some people think." He highlighted the episode of rising U.S. yields three weeks ago, in response to reports of the successful vaccine trials, as a taste of what could be ahead on a bigger scale. "Steepening of the yield curve I think when you have good news is absolutely not a problem, but markets tend to overshoot and a strong increase in rates in a normalization period would not be welcome."

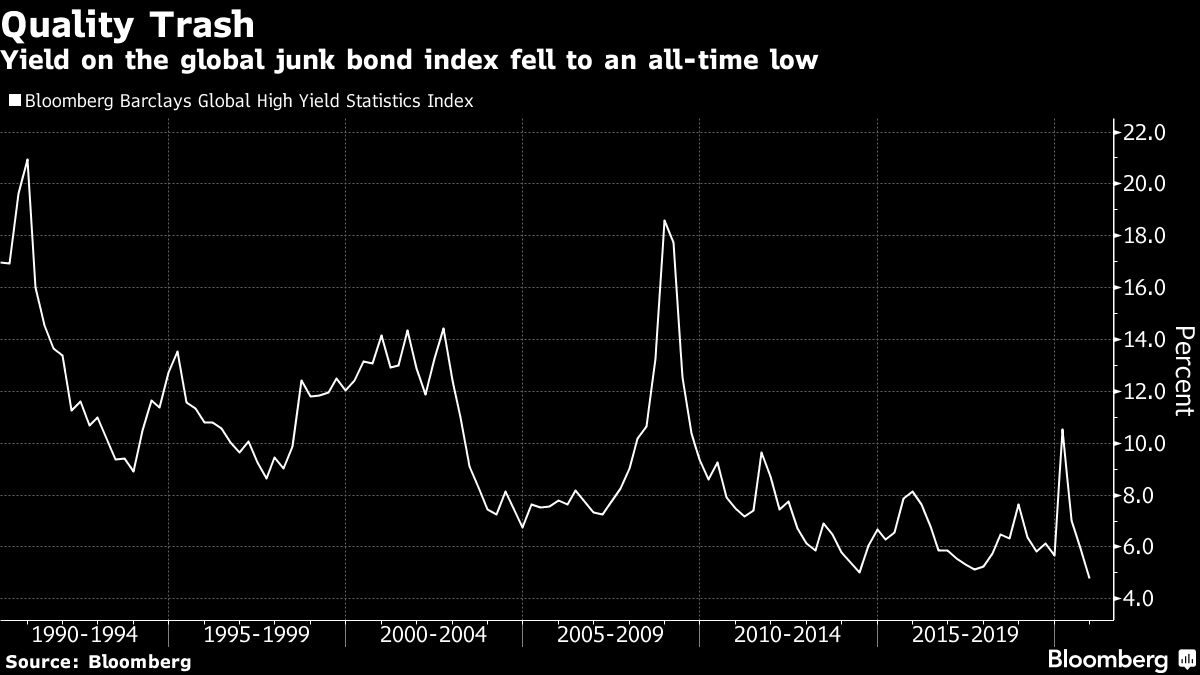

Clearly the Fed shares these concerns, judging by the FOMC's signaling in minutes from the November meeting that it's preparing forward guidance for its quantitative easing program, which is widely expected from its Dec. 15-16 get-together. Policy makers will want to set some parameters around an intervention if markets get unruly enough to tighten financial conditions. While they're at it, they can lay the groundwork for the economic terms or timeframe for withdrawing support -- well in advance -- to prevent a hostile response. And the mere hint of a plan has stirred a little noise lately about the possibility of another taper tantrum. Chairman Powell isn't explicit about any concerns over a repeat of the May 2013 Treasury-market hissy fit that blew up at the merest hint of a slowdown in asset purchases. His concern may be most evident from what he doesn't say. "Normalization" was a pretty common subject for his predecessors Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen. But Powell has barely uttered that word since early 2019 when the Fed's balance sheet unwind was drawing unanticipated and unwelcome attention in volatile markets. Even as U.S. growth data started faring better than expected, he has been at pains to stress that the central bank will use its full range of tools for as long as necessary to support the recovery. Powell is also adamant that he's not even thinking yet about that thing he's not saying, telling Congress this week that "the time will come to start thinking about balance sheet issues, and we have the model of what we did in the last financial recovery... It's well into the future. I think we know how to do it -- that's slowly and carefully." The market may also be less prone to a sharp reversal than it was in 2013, as recent data from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission showed asset managers have already slashed their net long positions in ultra-long bond futures to the lowest level in four years. As for when the Fed is likely to embark on that riskiest of central bank endeavors, TD Securities' head of global rates Priya Misra doesn't see any tapering until 2023. That's in part because the firm sees a pullback in asset purchases signaling a rate hike in the following two years, and the earliest TD has penciled in for that is 2025. Moreover, Misra says, there's the risk that the government's massive borrowing needs could drive costs up for everyone unless the Fed keeps pace. "If there are no longer-term scars from the pandemic, if all goes to normal post the vaccine, and if inflation overshoots, and earlier taper is possible," she said. "But there are a lot of ifs in that statement." High Yield-DiveAs my colleague Katherine Greifeld pointed out in her Fix last month, the term high-yield debt has become a serious misnomer in the current buy-anything-that-isn't-nailed-down market. The rate on the U.S. junk bond index fell to a record low in November, so it wasn't going to be long before the rest of the world followed. This week the Bloomberg Barclays global high yield partied to the same milestone.  There are signs of this bond-fest getting upstaged, judging by the magnetic performance of equity exchange traded funds last month. ETFs tracking stocks pulled in a record $81 billion, compared with $17 billion for their fixed-income counterparts. The flows come as equities worldwide posted their largest monthly advance since 1988, and the broad-based gains included the best month ever for U.S. small cap stocks and even a 25% surge in energy shares. Not that this year's haul for bond funds is exactly humble. Inflows to fixed-income ETFs this year surpassed the 2019 record of $154 billion with three months to spare, thanks in large part to the Fed's credit purchase facility introduced in April. And they're still pulling in assets, even since the confirmation of that facility's expiry at the end of the year. The positive reading on all this is that financial markets may be starting to count less on the central bank's support after all. At least, that's the takeaway from Bryce Doty, portfolio manager at Sit Fixed Income Advisors. He's now focusing his investments in inflation bonds, cyclicals "and nearly everything the Fed wasn't buying and distorting/propping up over the past six- to eight months." "It feels like a lot of cash that was sitting on the sidelines is coming into the market again,'' he said. ``It's almost like the Fed decided to start pumping a bunch more money into the financial system, but they haven't." Bonus pointsWhere are you in the queue for the vaccine? Oligarchs, they're just like us! "I'm 27 years old, I'm being sued by my mother...I'm drinking a lot." Best books of this blasted year Dudley's five reasons to worry about faster U.S. inflation Movers and ShakersPoint72 quant consolidation spurs departure of one of its most prominent executives Nomura is on a hiring spree for its wealth and fixed income business in Asia Richest raises are for credit traders after this year's mayhem Lloyds names HSBC's Nunn as new CEO Former Bank of America Executive Appointed as Johnson's Top Aide Millennium hires two for its $1 billion macro hedge fund spinoff BofA's European credit trading head leaves to set up new fund |

Post a Comment