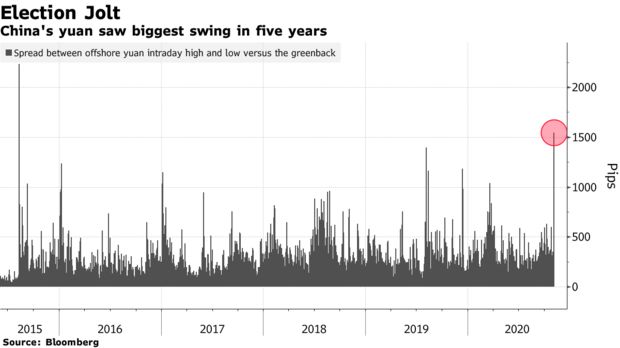

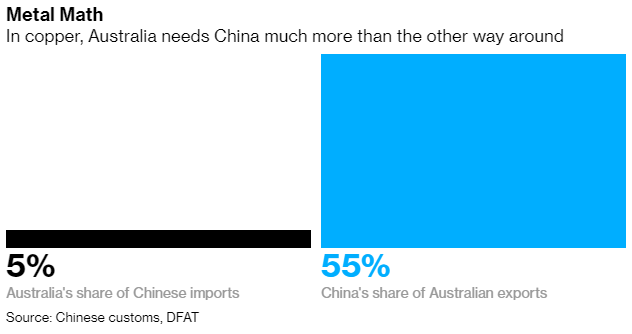

| This newsletter declared in its previous edition that Jack Ma had conquered finance. We spoke too soon. In a shocking move this week, the much anticipated IPO of Ma's Ant Group was put on hold. The $35 billion initial public offering would have been the biggest of all time and made the fintech behemoth China's most-valuable finance firm. In explaining the halt, officials have cited a new regulatory regime for financial holding companies that will increase capital requirements for Ant and alter the outlook for future earnings. With none of that disclosed in Ant's prospectus, authorities have argued it was better to pull the plug at the last minute than to allow a "hasty" IPO to continue. While plenty of investors will agree with that rationale, it's also an explanation that falls short of being wholly reassuring. Among the most conspicuous questions left unanswered is why regulators let the listing progress so far before intervening to stop it. It's hard to imagine policy makers were caught unaware, given the ubiquitous media coverage of the listing. Ant's businesses were also well established, including the lending it does in tandem with banks and trusts that has been the target of the greatest scrutiny.  Jack Ma during an interview at a Paris conference in May 2019. Photographer: Marlene Awaad/Bloomberg One popular explanation has been to link the timing of the intervention with Ma's appearance at a forum in late October during which he publicly accused financial regulators of stifling innovation. The implication being of course that the suspension of Ant's IPO was retribution. Given the dearth of publicly available information about the decision-making process that went into shelving the listing, we will probably never know for sure if Ma's criticism was the catalyst. That's a concern. The sequence and timing of how Ant's IPO collapsed will prompt foreign investors to wonder how committed China is to the kind of transparency needed in a modern and robust capital market. Surprises of this size do not inspire much confidence. Presidential SwingsAs of the publication of this newsletter, the outcome of the U.S. presidential election was as yet unsettled. It did appear, however, that Joe Biden was on the brink of taking the White House from President Donald Trump. No matter the winner, the implications for China are obviously large, a fact that's been exemplified by the significant swings seen in its currency. Trading of the yuan offshore saw it rise as much as 0.9% late on Wednesday in Asia, after it appeared that Biden had gained the advantage. Analysts view a Biden administration as being potentially more moderate, or at least more predictable, when it comes to ties with China. Earlier that same day, when it seemed Trump might win reelection, the yuan had fallen as much as 1.4%. That represented the biggest intraday swing in more than five years.  Doubling DownPresident Xi Jinping unveiled a goal this week of doubling the size of China's economy by 2035. That would seem a fairly ambitious target given that the country, with its gross domestic product now at about $14.3 trillion, is already the world's second-biggest economy. Doubling would push China's GDP past $28 trillion and put it in position to overtake the U.S. economy, which is currently about $21.4 trillion in size. To get there, Beijing will need to average about 4.7% growth each year over the next 15 years. While Chinese annual growth in the past two decades has substantially exceeded that rate, pandemic-hit 2020 being a notable exception, there is no guarantee Beijing can keep it up. And with U.S.-China ties becoming increasingly confrontational, there will also be no shortage of pitfalls ahead. Australian ConflictTensions between China and Australia appear to be escalating. Beijing this week told Chinese commodities traders that they should stop importing Australian coal, barley, copper, wine, lobsters, sugar and timber. The verbally delivered edict represents a significant deterioration of ties that have been strained since Canberra banned Huawei from its 5G network in 2018. The resulting trade spat, unfortunately for Australia, has been relatively one-sided. Copper is an example of this asymmetry. About 55% of Australia's mined copper exports were shipped to China last year, but those Australian shipments made up barely 5% of China's total supply of the metal. That makes it notably easier for China to replace Australia as a supplier than it is for Australia to replace China as a market. It's no surprise then that as China presses its advantage, Australia has accused Beijing of being a bully.  What We're ReadingAnd finally, a few other things that caught our attention: |

Post a Comment