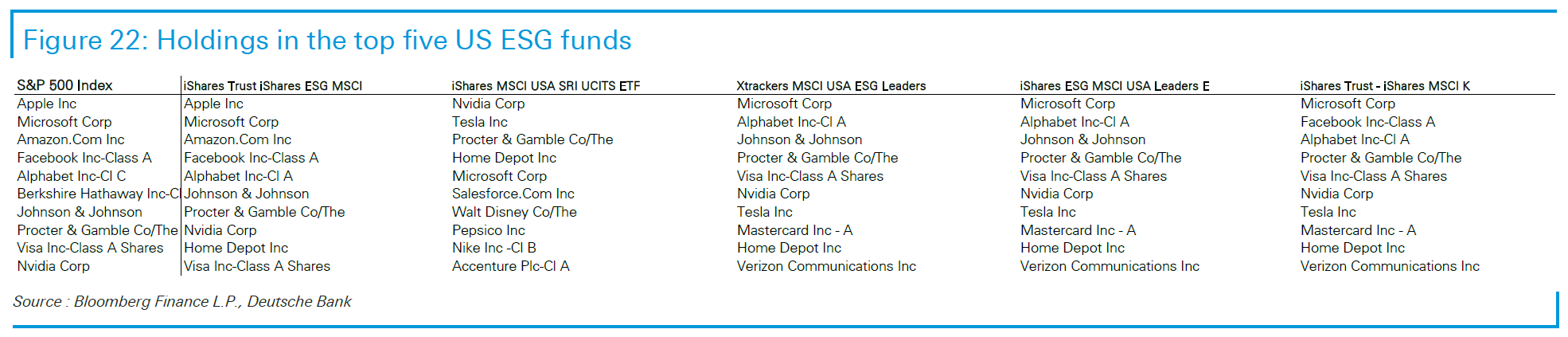

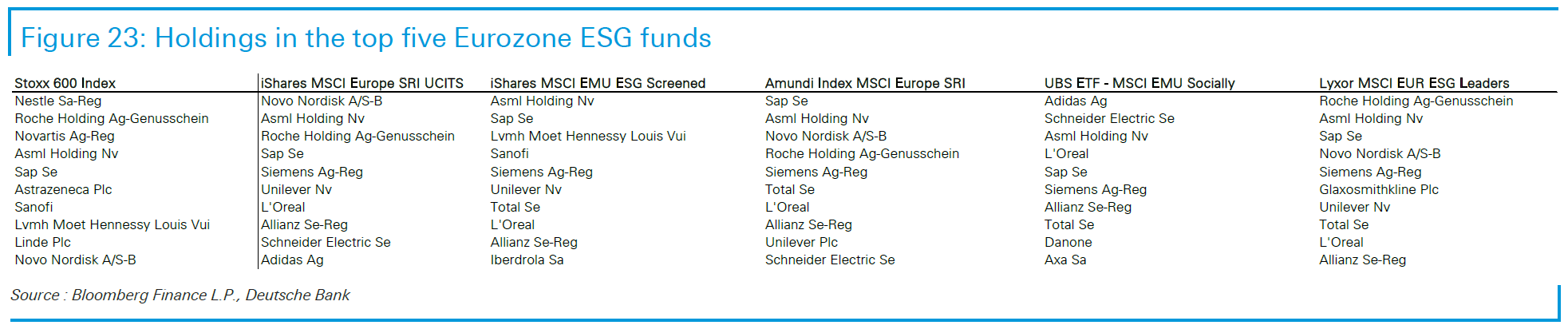

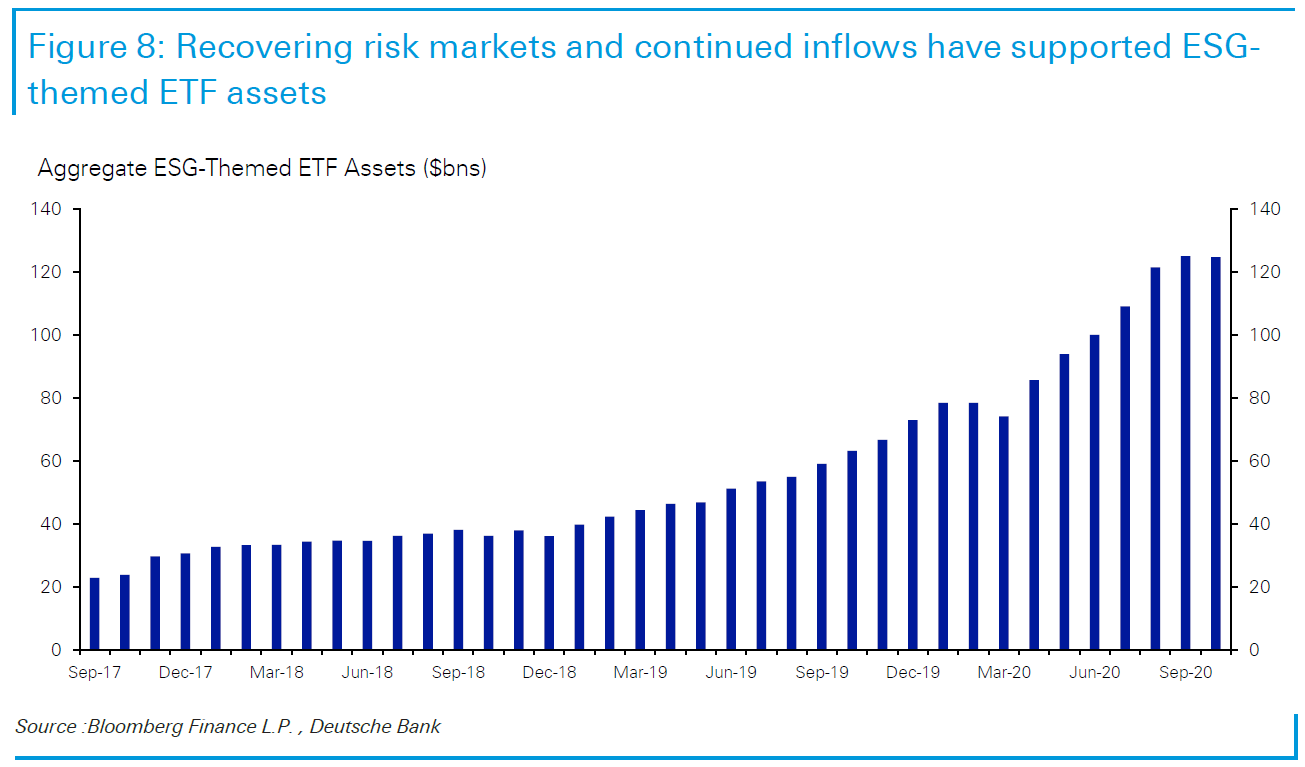

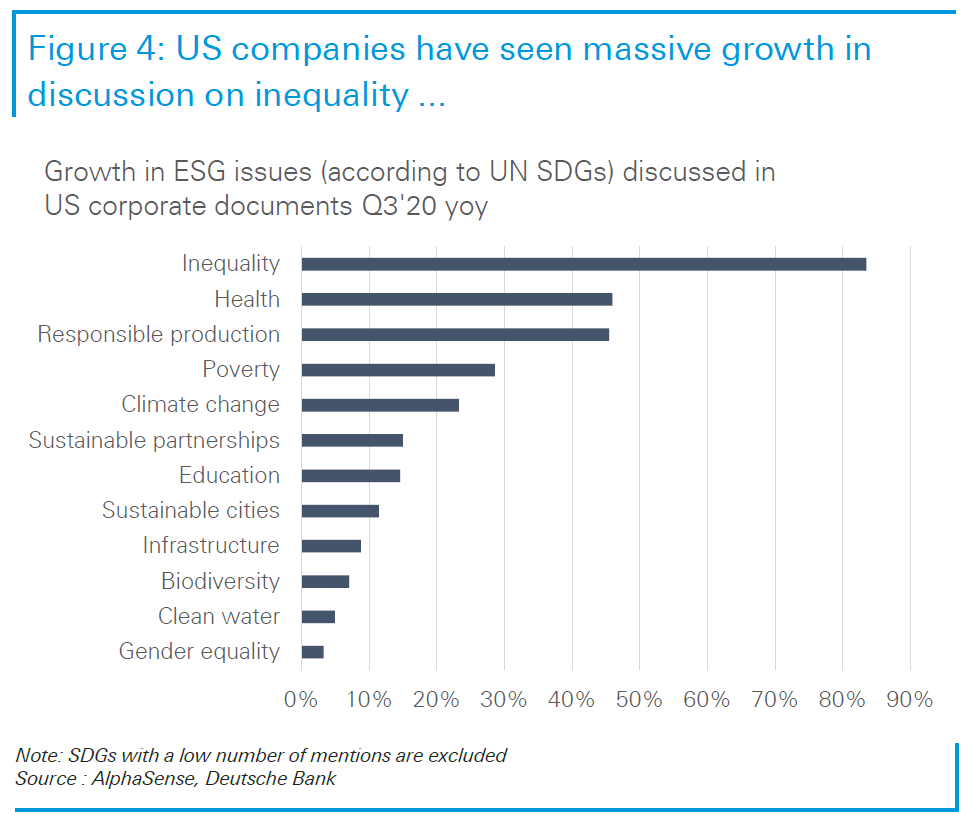

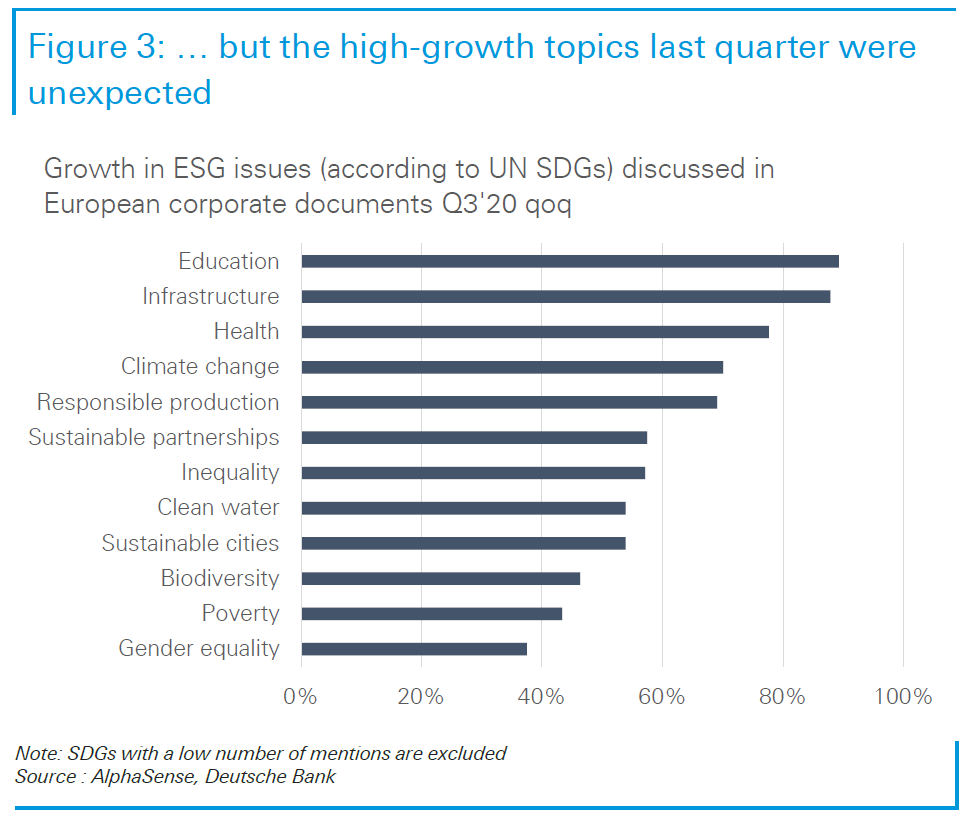

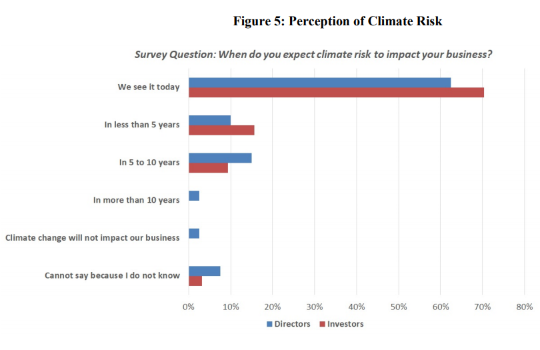

Capitalism, Freedom and ESG What was once ethical investing became socially responsible investing, and now it has become ESG. And it is at the heart of some of the most fascinating debates in investment. The entire notion of capitalism and how it should work is at stake. In Europe, the idea that environmental, social and governance principles should form a part of investment decisions is now widely accepted. In the U.S., it is different. The pandemic has shed much light on the debate. I will come to the newest data below, but first, let me recap. Pivotal to discussion in the U.S. is an essay the great conservative economist Milton Friedman wrote for the New York Times magazine 50 years ago. It concluded as follows, with the ringing declaration that companies don't have "social responsibility," merely a duty to maximize profits while staying within the law: [T] he doctrine of "social responsibility" taken seriously would extend the scope of the political mechanism to every human activity. It does not differ in philosophy from the most explicitly collectivist doctrine. It differs only by professing to believe that collectivist ends can be attained without collectivist means. That is why, in my book "Capitalism and Freedom," I have called it a "fundamentally subversive doctrine" in a free society, and have said that in such a society, "there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception fraud." The notion of "shareholder value," and an unapologetic attempt to maximize profits, gained sway over the ensuing years, and helped spur the bull market of the last two decades of the 20th century. The Times published this great collection of essays about it on the 50th anniversary. Since the turn of the millennium, however, the view has gained force that shareholder value led to the weakening of the fabric of American society, and stoked inequality, while companies failed to make the investments necessary to ensure long-term economic growth. In response, the Corporate Roundtable, one of the biggest employer organizations in the U.S., published the following set of principles a year ago: While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders. We commit to: •Delivering value to our customers. We will further the tradition of American companies leading the way in meeting or exceeding customer expectations. •Investing in our employees. This starts with compensating them fairly and providing important benefits. It also includes supporting them through training and education that help develop new skills for a rapidly changing world. We foster diversity and inclusion, dignity and respect. •Dealing fairly and ethically with our suppliers. We are dedicated to serving as good partners to the other companies, large and small, that help us meet our missions. •Supporting the communities in which we work. We respect the people in our communities and protect the environment by embracing sustainable practices across our businesses. •Generating long-term value for shareholders, who provide the capital that allows companies to invest, grow and innovate. We are committed to transparency and effective engagement with shareholders. Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to deliver value to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country. From shareholder value, we had moved to "stakeholder value." Even the biggest capitalists in the U.S. seem now to accept that they must take the interests of more than just their shareholders into account. As it has reached its anniversary, this declaration has spawned some further interesting commentary. But if there is growing acceptance that companies can take more than profits into account, there is still resistance to the idea that investors can do the same. Earlier this year, Eugene Scalia, the secretary of labor and son of the revered conservative Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia, released a proposed rule that would effectively thwart most company pension funds in the U.S. from investing using ESG principles. He found that they conflicted with the rules laid down by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, or Erisa. He expressed himself most clearly in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal. Here is the key passage: At the heart of Erisa is the requirement that plan fiduciaries act with an "eye single" to funding the retirements of plan participants and beneficiaries. This means investment decisions must be based solely on whether they enhance retirement savings, regardless of the fiduciary's personal preferences. The department's proposed rule reminds plan providers that it is unlawful to sacrifice returns, or accept additional risk, through investments intended to promote a social or political end. Sometimes, ESG factors will bear on an investment's value. To give an obvious example, if a factory is leaching toxic chemicals into groundwater, lawsuits and regulatory action are likely to follow, sapping profits. A corporation with dysfunctional management will also typically be a poor investment. But ESG factors often are touted for reasons that are nonpecuniary—to address social welfare more broadly, rather than maximize returns. One prominent firm's manager has said that its funds may choose investments that offer a below-market rate of return but further the firm's goal of having a "positive effect on corporate behavior and to promote environmental and social progress." That trade-off may appeal to some investors, but it is not appropriate for an Erisa fiduciary managing other people's retirement funds. I wrote earlier this year that I thought Scalia was wrong about this. If a pension fund's members felt strongly about some issue, there was no reason why the law should stop them from investing accordingly; and plenty of people invest in ESG because they think it will make them money. It's supposed to be enlightened self-interest. Beyond that, it is odd to politicize the issue, as this think piece from Vontobel Holding AG points out. It looks like an attempt to enforce the Friedman philosophy at a point when the business and investment communities had made their peace with moving on from shareholder value. In Europe, ESG seems to have taken off with far less controversy. Now, after the last six wrenching months, how has the debate been affected? In the U.S., it is hard to see how any pensioners would have been upset. The MSCI index of U.S. companies with strong ESG factors has done as advertised and matched the market as represented by its MSCI USA gauge almost perfectly. MSCI's ESG "select" index of the top 100 stocks on these principles has obviously captured many growth companies. It easily beats the the main index, and looks in practice like a watered-down growth index. The value index, in which Erisa funds are free to invest, has had a horrible time:  Emerging markets show exactly the same pattern. In markets where governance issues are particularly important (in other words, where you are less sure the law will protect you if a company absconds with your money), ESG has particular appeal:  When we look under the hood, we do find something concerning, which is that ESG funds seem to be overloaded with currently fashionable stocks, particularly the FANGs. This survey of the biggest U.S. ESG funds repeatedly shows names like Facebook Inc. (which many would exclude on social grounds), and Tesla Inc. (whose governance record is surely questionable) among the top holdings. Are they really ESG stocks?  Meanwhile in Europe, which lacks a few huge and largely non-polluting tech companies, there is a wider range. Intriguingly Total SE, a French oil company, is a popular ESG stock:  Commercially, those marketing ESG funds seem to have won the argument (possibly helped by the fact that their screens lead them into the hottest FANG stocks). The growth in assets held globally by ESG exchange-traded funds has been phenomenal. They have multiplied fivefold in three years, as this chart from Deutsche Bank AG shows:  This is mostly down to new inflows of capital, rather than market appreciation. Over the last four years, ESG ETFs have never suffered a monthly outflow:  Scalia's rule therefore seems to be stopping investors from making a choice that they might well have made, if given freedom to choose (as Friedman might have put it). How exactly has ESG changed corporate priorities? Deutsche this week published a report by Luke Templeman (a former colleague) and Karthik Nagalingam which included an exhaustive study of the language used in corporate documents about the issues laid out in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, carried out for them by AlphaSense. The results are fascinating. Over the last 12 months, U.S. companies have become very preoccupied by inequality:  In Europe, health hogged attention; although inequality is also a great concern there:  European companies' concerns turned sharply over the summer. With reopening schools causing angst across the continent, and preoccupation over how the continent can grow its way out of the pandemic, education and infrastructure are becoming priorities:  For another approach, Columbia Law School's Ira M. Millstein Center for Global Markets and Corporate Ownership surveyed 130 senior directors and investors in the U.S. and Europe on how significant they considered climate change to be to their business. This is important to ESG debate; if climate change is a material risk, then even the Scalia/Friedman school of thought can support companies and investors giving it priority. It looks as though they do indeed find the issue very material:  There are plenty of reasons to be concerned about ESG. Shareholder value is a clear concept while stakeholder value is amorphous. As I've written, ESG definitions are all over the place, particularly when it comes to governance. And some of its popularity may well be due to the happy coincidence that it offers exposure to the hottest stocks of the moment. On the greater philosophical debate, the scales seem to me to be weighing firmly in favor of stakeholder value and ESG, rather than Milton Friedman's notion of shareholder value. Survival Tips You never know what will strike a chord. Yesterday I recommended Cantus In Memoriam of Benjamin Britten by the Estonian minimalist composer Arvo Part. I am amazed and happy to discover that Estonian minimalism is popular with the Points of Return readership. So let's have some more. One reader recommended this recording of Part's Credo, with Helene Grimaud on piano under the Finnish conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen. You can also see Grimaud playing on this live version, recorded in Johvi, Estonia. It brings across much of the excitement of this glorious but bizarre work. However, my preferred version is this one, under the Estonian conductor Neeme Jarvi. I admit I am biased, because I am singing in this recording, which was made at a drafty church in Tooting, South London, back in 1992, with the composer in attendance. To be more precise, I sang, whispered and shouted, back when I performed with the Philharmonia Chorus. On balance, it's the weirdest piece of music I know. The experience of recording it was made all the more bizarre by the fact that every take would be followed by an impassioned burst of Estonian from the composer over the tannoy, which would fill the church like the voice of God. As Jarvi was the only person present who understood Estonian, we would stand and try to work out what we had done wrong from the composer's tone of voice and the conductor's body language. Meanwhile, the percussionists and brass players at the back were physically spent by each take. At one point I remember the timpanist turning to the others and asking: "Anyone hurt?" I won't say anything more about it. If you have time in your busy days to listen, I'll be fascinated to hear what you make of it. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment