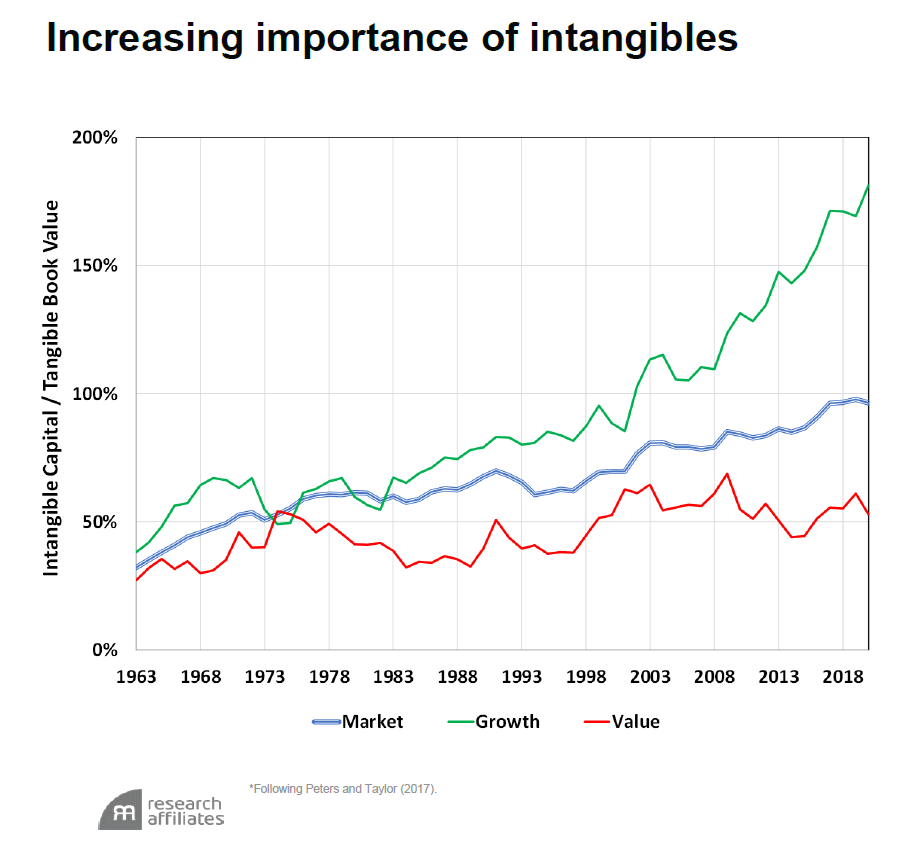

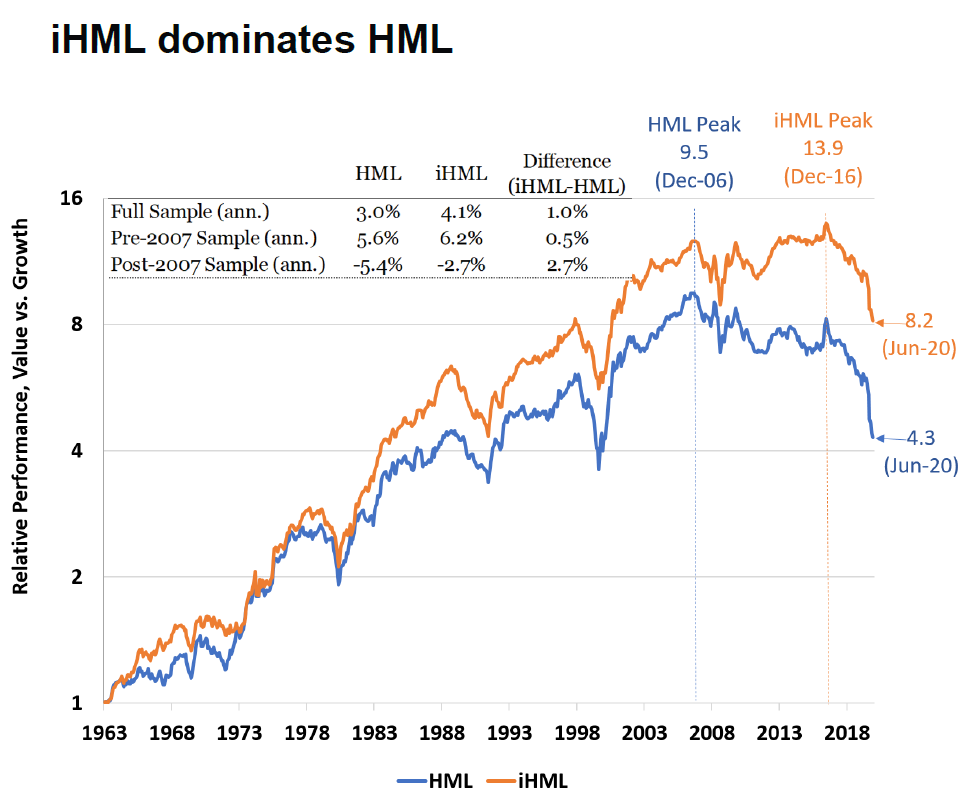

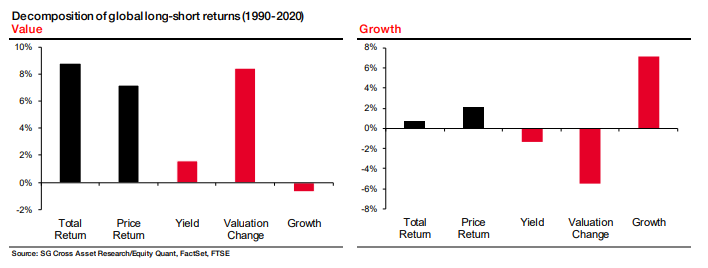

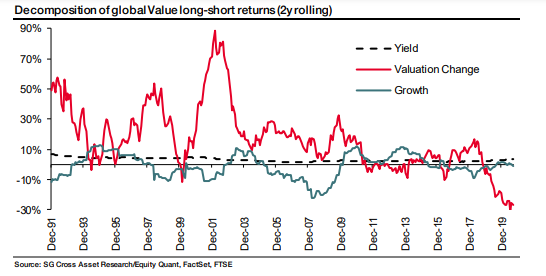

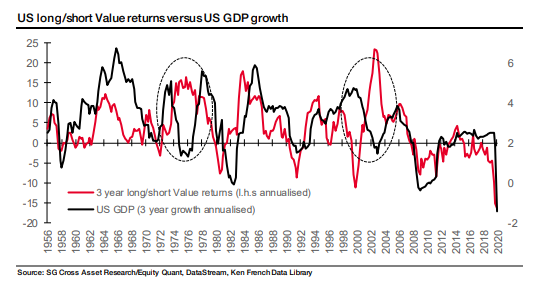

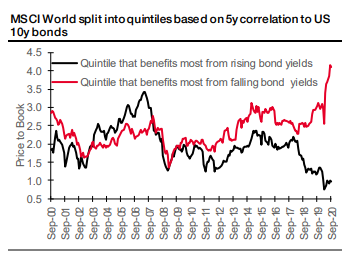

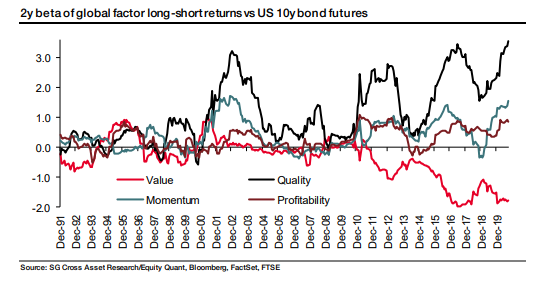

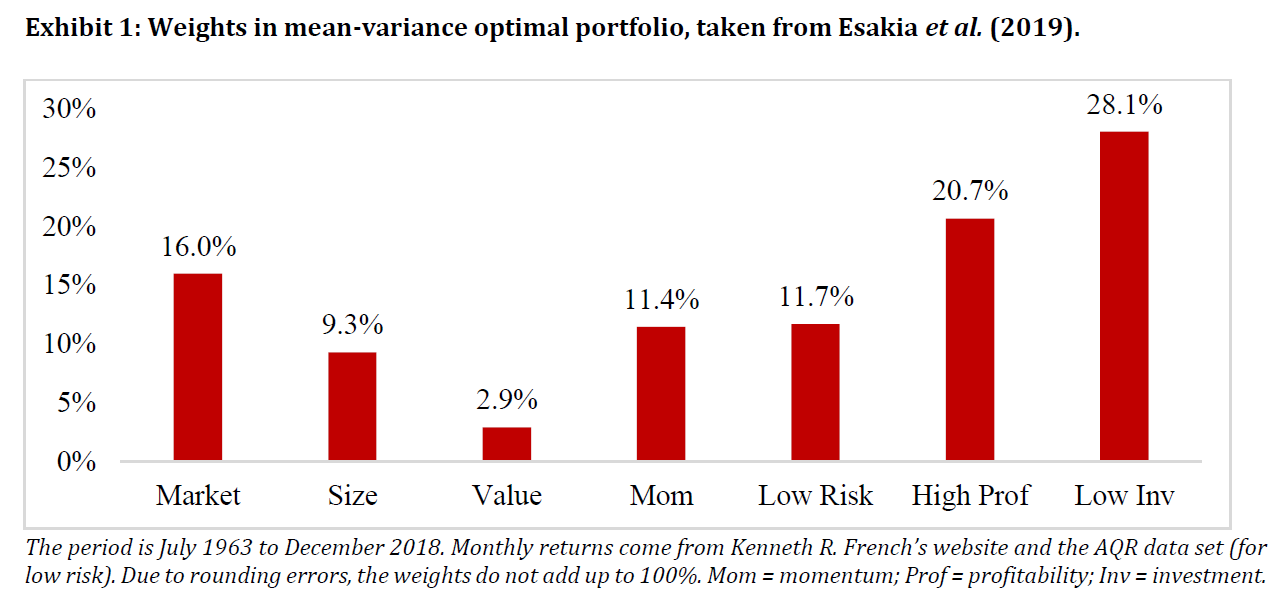

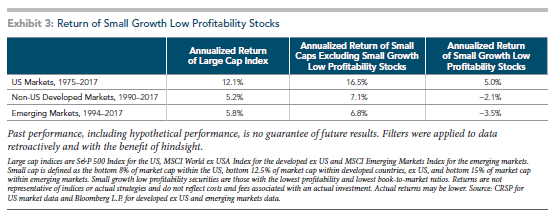

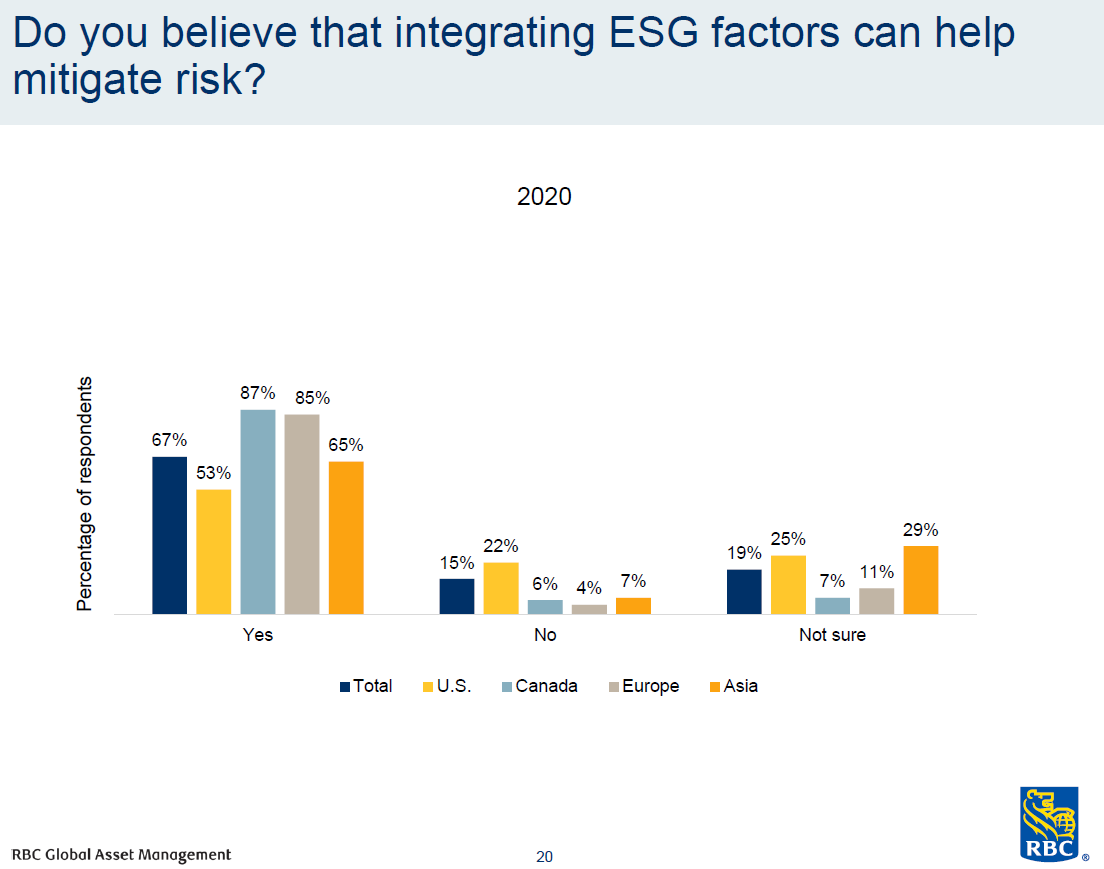

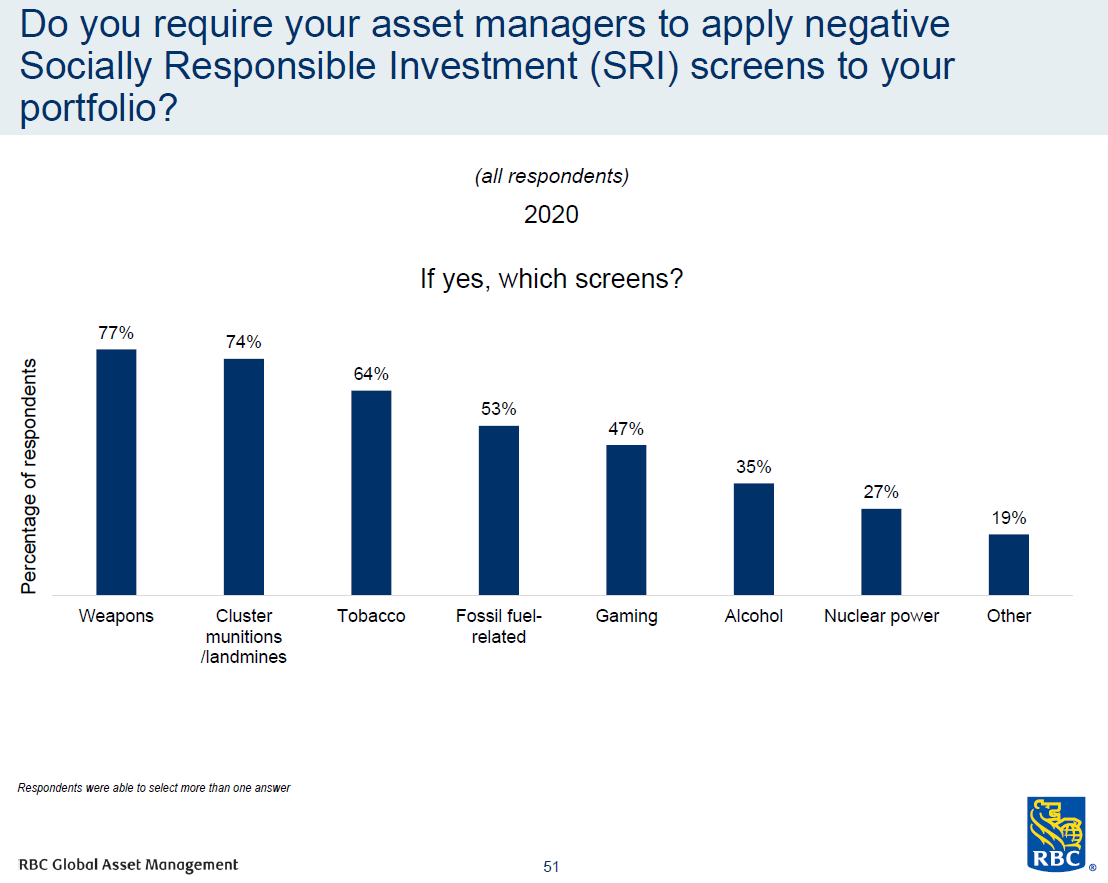

Our Survey Said…! A lot of the "surveys" that come across journalists' desks are thinly veiled pleas for attention. Similarly, academic studies can often be driven by the extreme incentive for young professors to see their work published. But some of the surveys and articles that drop into my inbox are genuinely interesting. As Wednesday was a blissfully quiet day on world markets, and I suspect there won't be too many more for a while, let me take a chance to share some of the most intriguing research I have seen in the last few weeks. It all has the common theme of how to beat the market in the long run. Value One of the first and most reliable ways to beat the market is value investing, promulgated brilliantly by Benjamin Graham in the 1930s, adapted by luminaries such as his pupil Warren Buffett in the years since, and identified as a quantitative factor that will predictably outperform in the long run by Eugene Fama and Kenneth French. At its simplest, it holds that stocks which are cheap compared to their book value (or some other sensible measure) will do better over time. It even has common sense on its side: "Buy stuff for less than it's worth and you'll make money." The only problem is that value has underperformed by so much and for so long now, that the whole concept is coming in for re-evaluation. Two recent studies tackle the issue neatly. The first complaint, from Brent Leadbetter, Feifei Li and Juhani Linnainmaa, a group of academics sponsored by Research Affiliates, is that book value has become an incomplete and limited measure of a firm's size. Meanwhile, Campbell Harvey of Research Affiliates suggests that the critical issue can be solved, and the value style can to an extent be resuscitated, if we include intangibles. As he shows, a growing share of book value is in intangibles — and not coincidentally this is most true of growth stocks:  Companies with particularly high intangibles tend to be the kind of low-asset and very profitable tech companies that value managers wish they could buy. So Harvey recalculated the results for value stocks (known as HML in the literature) compared to growth stocks, to include intangibles in their book value (labeled iHML in the graph below). The bad underperformance of the last couple of years remains intact, but iHML has performed significantly better over the years, and didn't peak until 2018, a decade after conventionally calculated value.  Meanwhile, Andrew Lapthorne of SG Quantitative attempts to explain"Seriously… what's wrong with Value?" He does a lot of quantitative heavy-lifting. First of all, unsurprisingly, value's returns over the long term have come from improving valuation (the word "Duh!" comes to mind):  Generally, when you buy a stock that's cheap, it's fair to hope that it will get more expensive, relative to its fundamentals. The problem is that globally in the last few years, cheap stocks have unremittingly got cheaper still. Part of the idea of value investing is that the cheap price means you shouldn't lose too much money whatever happens. For some reason, it no longer provides that margin of safety:  Why is that? In part it is because value stocks tend to do badly relative to the market when the economy is doing badly. Value has done well during economic downturns twice in the past, but that was because those slumps helped to burst bubbles in the "Nifty Fifty" stocks in the 1970s, and in dotcom shares in 2000. It isn't surprising to see value tank when the economy does:  There is also a correlation between value stocks and the direction of bond yields, which also tend to be driven by the economy. When yields are falling, value does badly, and vice versa. Correlations between the most extreme growth and value stocks and the bond market have only grown stronger in the last few years, as yields dropped to record lows:  So value stocks are being victimized by the sluggish economy and low bond yields (and by the success of growth stocks in the current environment). But there is reason for hope. Value is the only major equity style that is negatively correlated with 10-year bonds. So if you want to hedge against a turnaround in the bond market, with prices falling and yields rising, value stocks are a great way to do it:  And of course it isn't such a bad idea to hedge against that eventuality. This is Lapthorne's conclusion: Value is important for diversifying valuation risk across all the other factors, which are not only extremely expensive, but also equally at risk from higher bond yields. Ironically, Value might be a better strategy if central banks lose control of the yield curve and/or inflation and Value makes money during a "Growth" bust, when market valuations implode under their own weight. There are plenty of things wrong with the Value factor, but there are also plenty of worrying things wrong with asset markets overall. Size A few weeks ago I wrote about a demolition report by Cliff Asness of AQR Capital Management LLC, arguing that the "size effect" (small companies tending to outperform large ones), never existed. It just appeared to work, said Asness, because small stocks are sensitive to the market. So just buy stocks that are sensitive to the market. That has provoked a response. ScientificBeta asserts that small companies still have a role — as a diversifier. When constructing an optimized portfolio, it turns out that an allocation to small-caps provides more diversification (or in other words helps move closer to the "efficient frontier" where risk and return are maximized), than value stocks. They are only a little behind the momentum factor (winners keep winning and losers keep losing), which has been far more successful recently:  Note that in this allocation, ScientificBeta found that the best results came with high-profitability and low-investment factors, both of which reward companies for not doing things that politicians would like them to do to help the economy grow (pour money into capex and eschew too big a profit margin). Meanwhile, Dimensional Fund Advisors LP points out that the small-cap phenomenon revives in full force, providing you exclude those with low growth and profitability. In other words, if you cut stocks that look destined to remain small, the remainder do fantastically:  A simple way to look at this is through the two most popular small-cap indexes in the U.S. The Russell 2000 includes stocks on the basis of their market value and nothing else; the S&P 600 screens out those that have failed to make a profit in the last year or last quarter. Both have their uses, but the S&P measure tends to perform better in the long term. That said, the S&P measure has lost a lot of its advantage during the disasters of the last few months. Explanations welcome:  ESG These days, environmental, social and governance, or ESG, is regarded almost as a factor in its own right, which can help reduce risk and improve returns. I covered the burgeoning debate on this yesterday. I now have another interesting survey, Global Adoption — Regional Divide by RBC Global Asset Management, which talked to 809 institutional managers across the world about their use of ESG. The survey confirms that investors are growing steadily less cynical and more likely to use ESG. It also confirms that there is still a sharp difference in perceptions between the U.S. and the rest of the world. That is clear from this chart:  When looking at traditional exclusionary screens, where managers exclude particular kinds of companies as being unethical, one finding jumped out. Weapons and landmine manufacturers are the most widely excluded, largely because this is legally required in a number of European jurisdictions. Tobacco, again unsurprisingly, comes next. But fossil fuels come next, ahead of gambling and alcohol stocks. Twice as many institutions exclude fossil-fuel companies as nuclear power. That is a huge change over the last generation, and indicates the scope of the challenge ahead for traditional energy groups:  If investors are growing less skeptical, there are still ample reasons to question the growth of "stakeholder capitalism" and what it aims to achieve. Last year saw a major commitment by a group of companies to prioritize more stakeholders and not just shareholders, under the aegis of the Business Roundtable. Now, research from Aneesh Raghunandan of the London School of Economics and Shivaram Rajgopal of Columbia Business School casts doubt on exactly how well the signers of that document have lived up to their commitment. The title of their research is Do the Socially Responsible Walk the Talk? In brief, the answer is "no." When comparing the companies bought by ESG funds with lists of those that have paid fines for breaking labor and environmental laws, they found the following: ESG funds' portfolio firms have significantly more violations of labor and environmental laws and pay more in fines for these violations, relative to non-ESG funds issued by the same financial institutions in the same year, undermining these funds' claims

that they are picking socially responsible stocks for inclusion. We further document that ESG funds' portfolio firms spend more money on lobbying politicians and obtain more frequent and higher-value government subsidies, suggesting that ESG funds' portfolio firms rely on higher levels of regulatory support relative to non-ESG funds. When it comes to governance, the trickiest of the three ESG concepts to pin down, it looks as though they are entranced by directors and executives with low nominal pay, who are paid a lot in stock, and that this prompts them to overlook many other governance problems. Significantly, this leads them to buy a lot of currently successful tech companies: Finally, we find mixed results with respect to ESG funds' performance on corporate governance: relative to non-ESG funds, ESG funds' portfolio firms have a higher percentage of independent directors and lower excess CEO compensation, but also have more entrenched managers ... The governance characteristics described are typical of high-technology firms, which often have powerful founder-CEOs with a larger number of nominally independent directors but voting rights that give these independent directors virtually no power. This characterization is consistent with our finding that ESG-oriented funds contain 24% more technology stocks than non-ESG funds issued by the same financial institutions in the same year. The report has too much detail and data to include here. This is the damning conclusion: we find no evidence that ESG funds actually pick stocks with better "E" and "S" relative to non-ESG funds by the same issuers – and, in fact, that on average ESG funds pick firms with worse employee treatment and environmental practices than non-ESG funds. A combined read of the evidence presented in the paper suggests that the correlation between the self-proclaimed high-ESG companies and high-ESG funds and their records is underwhelming. These results raise several questions about whether the declaration of high-minded ideals by firms is cheap talk and whether commercially available ESG ratings really capture a firm's ESG orientation. Much remains to be explored in follow up work. There is a role for ESG, but it mustn't become a front for whitewashing (or "greenwashing") companies that aren't in fact behaving responsibly, or for extracting extra fees from investors. Survival Tips As there seems to be enthusiasm for continued forays into Estonian music, let me offer up another possibility, by an Estonian composer who I hadn't heard of before. This is Paikeseratas by Olav Ehala, as performed at Estonia's national singing festival in 2014. Then this is Tahan olla oo (lacking a few accents I'm afraid), and this is Vaid see on armastus. This is more approachable than Arvo Part and also less profound, but the Estonian language and national choral tradition are beautiful. Further suggestions welcomed. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment