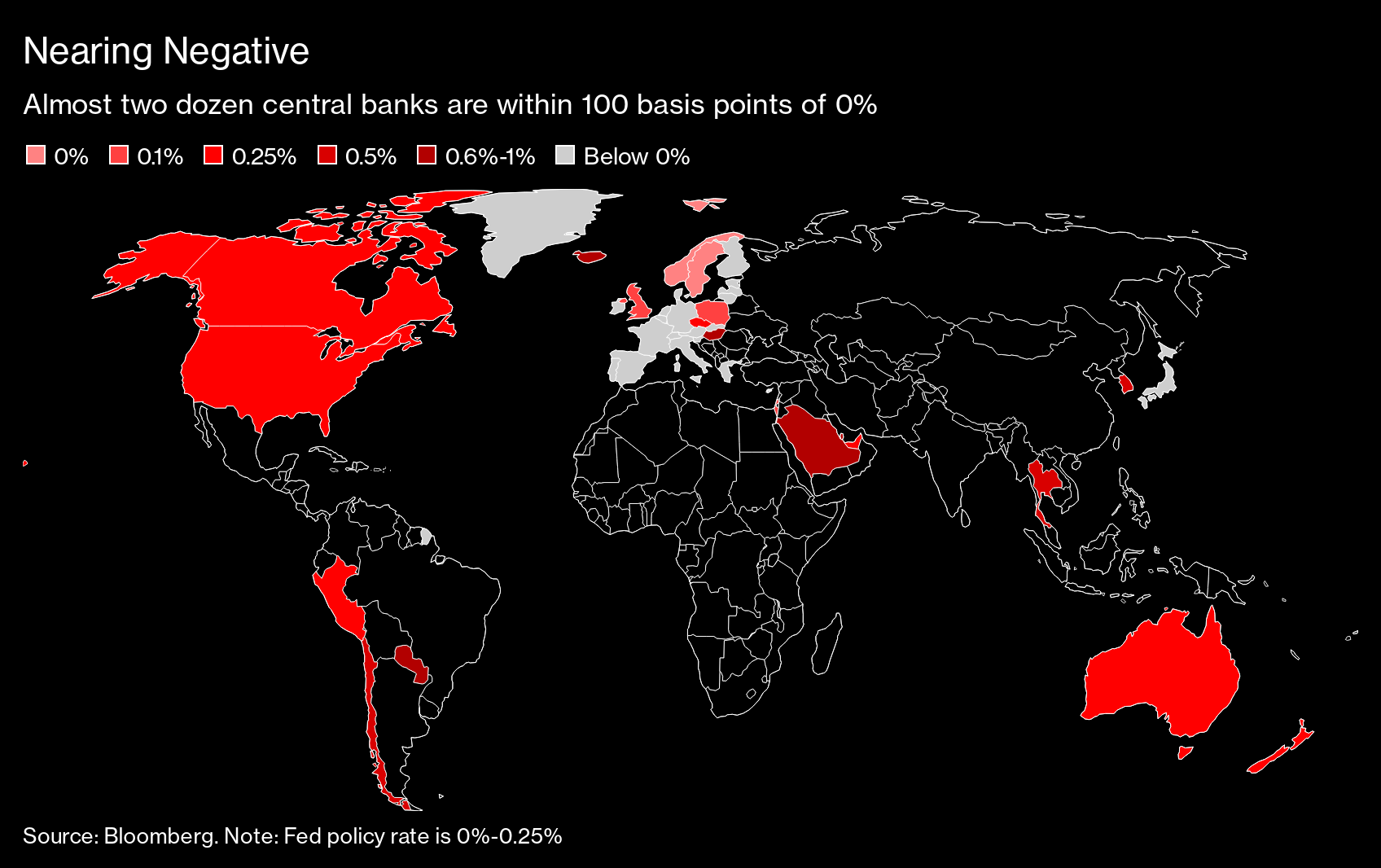

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that regularly mixes up Star Trek, Star Wars and Dr. Who -- so had to fact-check the Vulcan mind meld. –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter. Fed Buys Time If the market was disappointed by the Fed this week, it was an unexpectedly grown-up response. We're a long way from a tantrum, judging by the modest moves in Treasuries and abbreviated drop in stocks. That's a success for Chairman Jerome Powell, who could easily have had a meltdown on his hands. It's a tribute to how the Fed managed expectations in the leadup to the meeting, by keeping attention on the overhaul of its long-term goals -- its new 2% average inflation target. That proved a distraction from the more-immediate gap in its strategy, that is, when and how does it plan to shift its policy focus from market repair -- which is arguably complete -- more toward supporting the recovery. The Fed has several plausible reasons for not wanting to engage with this question just yet. First, as Powell has pointed out repeatedly, the government has a critical role to play in helping Americans -- the 11 million out of work -- and businesses through the pandemic. Talks on a fresh stimulus package appear to have made little progress since faltering over a month ago. Second, this meeting was the last before the presidential election, and any policy move that could spur asset prices could easily have drawn accusations of partisanship. And third, it has no reason to do anything at this stage. Bond yields are plying narrow ranges and swaps markets show investors are convinced that interest rates will remain low for years to come. The S&P 500 is still holding around its 50-day moving average, despite the surrounding economic destruction, and financial conditions -- which the Fed tracks closely -- show little sign of stress across key markets.  Powell did face questions about why the Fed provided no steer on its asset-purchase program (though they weren't quite as pointed as those addressing the poor take-up of its Main Street Lending Facility, which begs explanation). The Fed's statement provided only vague clues as to how long rates would remain on hold: until inflation runs "moderately above 2 percent for some time." But it seems the market prefers even a fuzzy guide to a defunct one (RIP Phillips Curve). The Chairman's response had a Vulcan mind-meld flavor, with repeated reference to the Fed's "very strong, very powerful guidance." This simply shifts the market's expectations for an announcement to the next meeting just after the U.S. election. Michael de Pass, head of Treasury trading at Citadel Securities, sees the Fed shifting the composition of its U.S. government-bond purchases to the longer end of the curve as a "foregone conclusion." Pump Up the Vol Speaking of the election, it's making its presence felt in the market: the customary calls for volatility around the race for the White House have an edge of urgency this year. First, there's the significant possibility of a change of administration: FiveThirtyEight's poll aggregator this week put the odds of Joe Biden winning the electoral college as high as 75.9%. Then there's the possibility of delayed results -- with mail-in ballots expected to reach record levels in the midst of the pandemic -- or the threat of a contested outcome. Homing in on the rates market, our Stephen Spratt says U.S. Treasury options are pricing the Decision Day 2020 as one of the biggest isolated event risks in at least a decade. He's looking at derivatives on the ICE BofA MOVE Index that measure expected swings in Treasury yields across the curve -- the gap is at levels seen only once since 2009 between options over a one- and three-month timeframe. The former is at an all-time low, and the latter captures the Nov. 3 vote.  This mounting anxiety -- apparent also in gauges of equity- and currency volatility -- could make it difficult for risk assets to recover their momentum. Corporate bond markets are already trudging against the tide of supply, as companies rush deals to market while conditions remain favorable. U.S. investment-grade bond sales have already surpassed the full-year record and the high-yield tally is on track for the same. It's interesting, then, how many notes in this humble bond reporter's inbox are touting bullish views on riskier credit. UBS strategist Matthew Mish sees this flood of supply slowing heading into the election and the year-end, and the bank recently adjusted down year-end targets for U.S. investment-grade and high-yield spreads. BlackRock Investment Institute favors high yield in a "moderately pro-risk" stance, on the basis that "the broad macro backdrop has been improving, risk assets have rallied a long way, and increasing market volatility points to risks that investors will need to navigate as the U.S. presidential election draws closer." (BII also sees the upshot of negotiations on another U.S. pandemic spending bill as "increasingly binary: a sizable fiscal package or nothing at all before the November election.") As for the scenario analysis, the best case for credit, according to UBS's Mish, would be a Biden win and a split Congress. In his view, that combination would probably lower the risk of higher corporate taxes denting earnings, and it could "reduce foreign policy risks" -- in particular, the growing investor angst about U.S./China relations that was highlighted in UBS's latest investor survey. And while we're consulting the wisdom of crowds, the latest Bank of America survey showed four in five investors reckoned a flip to a Democrat-controlled Senate would be a "risk-off" scenario. Though just 11% saw benchmark 10-year yields busting out of their 0.5-1% range before the end of the year. Let's see how these notions get shaken up, or not, by the first Trump vs Biden debate -- which airs Sept. 29, if you can bear to watch. NIRP Alert The Bank of England appears to be moving beyond a mere flirtation with cutting interest rates below zero. At this week's meeting, it announced a "structured engagement" next quarter, looping in the Prudential Regulation Authority to consider how negative interest rates policy might work in practice. This sparked a flurry of "save the date" trades in U.K. rates markets, with bets on rates hitting zero in February, and -0.10% after the summer. The two-year government yield slid back below -0.10%.  BOE Governor Andrew Bailey hasn't shown a lot of enthusiasm for negative interest rate policy (NIRP). But this latest nasty turn in Brexit may force his hand in a decision that could define his legacy, and not necessarily in a good way. Just a month ago, when Bailey conceded negative rates were a part of the BOE's toolkit, the Bank's Monetary Policy Report warned that such a move could further harm banks already facing loan losses as the pandemic closes more businesses and drives unemployment higher. "As a result, implementing negative policy rates might be less effective in providing stimulus to the economy at the current juncture than at a time when banks' balance sheets are improving," the August MPR noted. It's a step more central banks are likely to confront as the pandemic continues to batter economies around the world, and with interest rates across the developed world already scraping around zero. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand may be the next to take the plunge, as its benchmark bond yields are already there. RBNZ is focusing on the relative success story of Sweden's Riksbank: it's so far the only central bank that's managed to wrench free of NIRP, in 2019. Now its policy makers are hoping to avoid a return.  As for the BOE's dilemma, Bailey might want to savor what may well have been one of the monetary policy committee's last unanimous decisions Thursday. The MPC voted 9-0 to hold interest rates for now at 0.10% and leave the asset purchase program at 745 billion pounds ($967 billion). So far it still intends to wind down those purchases at the end of the year, but that'll be about the time that the UK runs out of time to reach a mind-bogglingly contentious trade- and border policy agreement with its European neighbors. Our BI economist Dan Hanson expects QE to remain the BOE's favored policy tool for now, with another 100 billion pounds likely to be tacked on to the program in November. But he also sees the Bank lowering its estimate of the effective lower bound at that meeting, and "it's becoming increasingly likely that if things turn sour in 2021 then negative rates could be used." Bonus Points "We're missing everything. People talking, the business," NYC cabbies talk about Covid-19 How climate migration will reshape America The billionaire who wanted to die broke is now broke The minefield of Covid-19 reopening, explored by an economist and demonstrated by the largest U.S. bank The Carnival cruise ship that spread coronavirus around the world Listen into the business case for climate action. (For one, there'll be a world as we know it to do business in.) Judy Shelton's path to the Fed Board is looking rockier |

Post a Comment