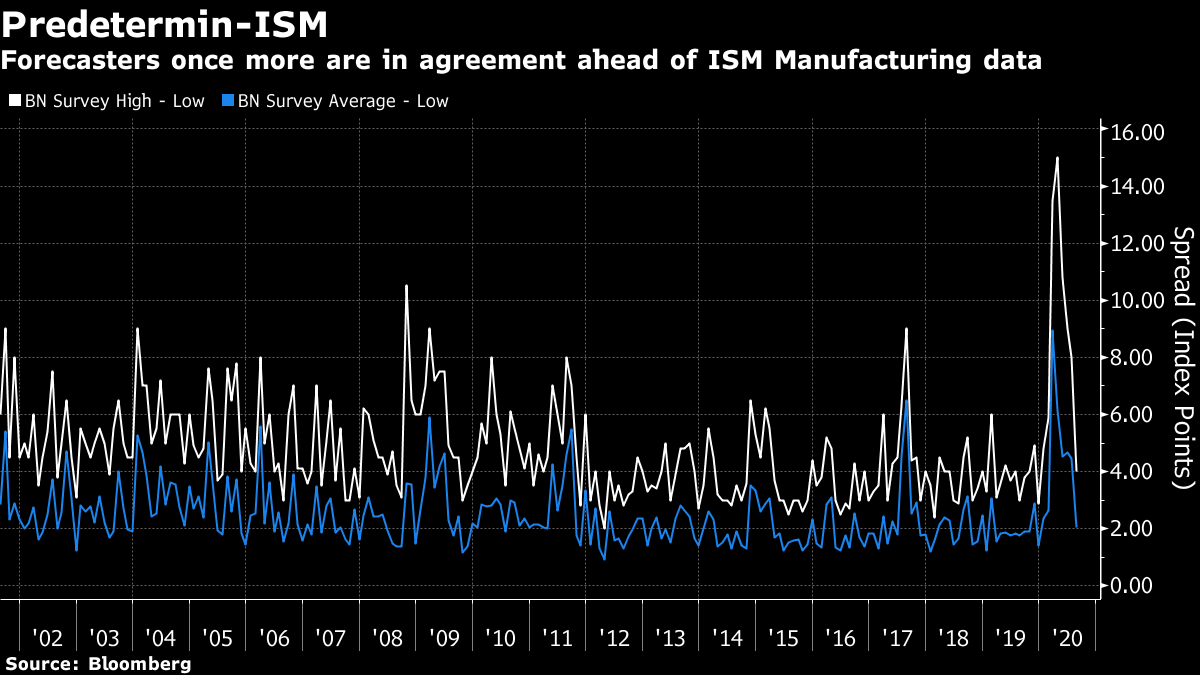

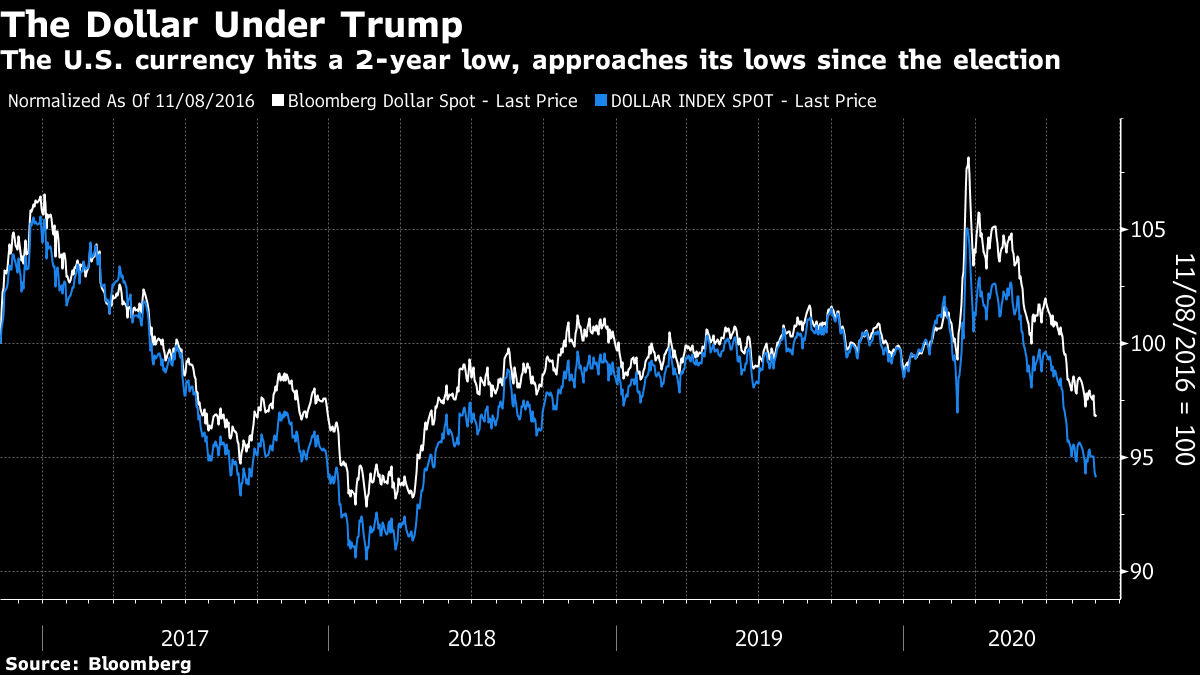

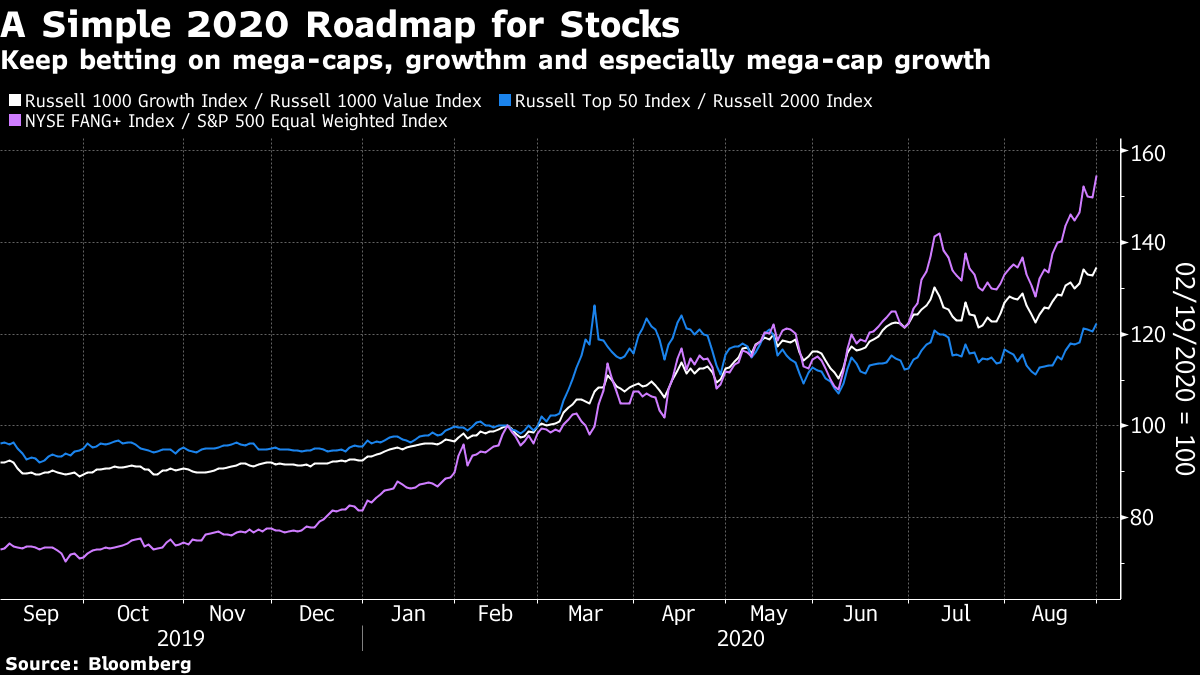

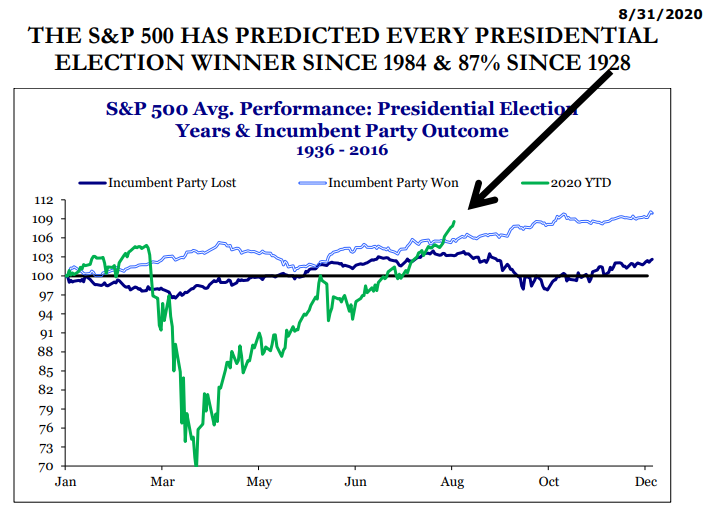

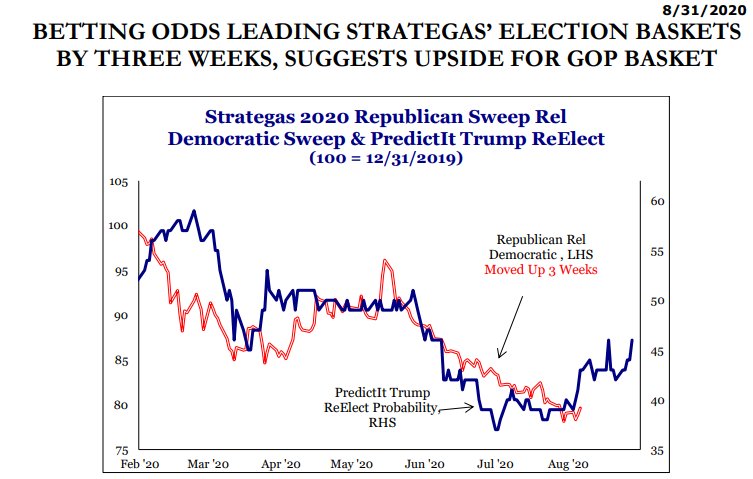

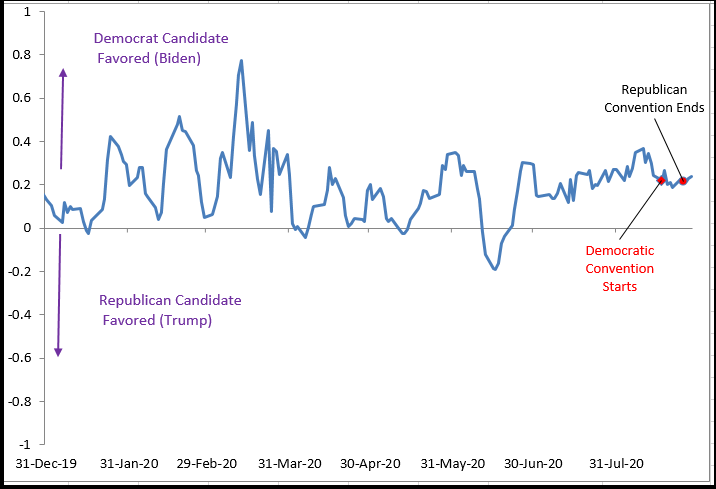

The Signal From the FedAmid much excitement, it is important to maintain the distinction, as outlined by political analyst Nate Silver, between the "signal" and the "noise." For world markets, the signal came through loud and clear, and few beyond the markets paid much attention. Let's start there. After a weekend to think about what Jerome Powell said last week, about moving to a flexible average inflation target (in other words, being prepared to let inflation go higher), investors decided not to fight him. The result was that 10-year inflation breakevens rose, above 1.8%, to their highest level this year. Meanwhile, with nominal yields held in check by the Fed (at least as far as traders assume), the real yields available on 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, or TIPS, dropped to an all-time low:  Beyond the comfort that comes with a Fed that can be predicted for years into the future, there is also the comfort that comes with thinking that you at last have a grasp on where the economy is heading, after a few months of disorienting uncertainty. Tuesday will bring the manufacturing ISM survey, one of the most reliable leading indicators. Earlier this year, the gap between the highest and lowest estimates reported in advance to Bloomberg News, and the gap between the average and lowest, rose to by far the widest ever seen. Not even the 2008 crisis saw such dispersion. Now, the expectation is for a continuing improvement, and the forecast spread is tighter than normal. It's as though everything is pre-determined:  Low yields had exactly the effect on the U.S. currency that might have been expected. The dollar index, which compares the currency to a small group of major peers, and Bloomberg's broader gauge, which also includes emerging currencies, both hit two-year lows, and are approaching the trough they reached a year into the Trump presidency. As the president has been vocal in wanting a weaker dollar, this will be good news for him:  All else equal, that weaker dollar depresses the relative performance of U.S. stocks. But the effect of lower yields and the way that a cheaper currency flatters overseas earnings helped the S&P 500 hit a new all-time high versus the rest of the world, for the first time since the pre-Covid peak in February:  I wrote in July that we were on course for a market regime change. The weaker dollar is happening. The shift to outperformance by non-U.S. stocks hasn't happened yet. Meanwhile, low yields have ensured that the same strategies for allocating capital within stock markets are working as well as ever. In short, and you've heard this before, mega-caps are still beating small-caps, growth is beating value and, in particular mega-cap growth stocks (aka the FAANGs, at fresh highs Monday) are beating the living daylights out of everyone else. The following chart is normalized to show how all of these trends have played out since Feb. 19, the day of the pre-Covid high:  That's the signal which matters most to markets. While the Fed remains on side, and keeps the economy from inflicting any new unpleasant shocks, the same trades keep working. The Noise From Prediction MarketsFar noisier, and of far greater interest to most of us, has been the U.S. presidential race. As I detailed yesterday, prediction markets have suddenly moved in the last few days to show a very tight race for both the presidency and the Senate. For most of the summer, a Biden victory coupled with Democratic control of the Senate was seen as the clear if not overwhelming front-runner. This raises the issue of how seriously we should take prediction markets. The economist Justin Wolfers led the way in researching prediction markets, which have been around longer than opinion polls; there was trading on elections in Wall Street as long ago as 1884. You can find a blog post I wrote on Wolfers' ideas here, written during the 2008 campaign. Earlier work by Wolfers showing that prediction markets assimilated new information swiftly and were difficult or impossible to manipulate, can be found here (from 2006) and here (from 2012). Prediction markets have money at stake, and offer a disciplined mechanism for incorporating all known information. Their record at predicting sports events and elections in the past has been startlingly good. They should not be lightly dismissed. Against this, they are still ultimately aggregates of opinions, which can be wrong. And they are vulnerable to the same problems as all other markets. They suffer from behavioral biases, and they will be led astray by inaccurate information. This happened in 2016, when they failed to predict either Brexit or the victory of Donald Trump, and they didn't see the coming victory of Joe Biden in this year's Democratic nomination process until the last moment. As Vox points out, prediction markets even had Mike Bloomberg, who controls Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg News, as the most likely Democratic nominee. Political bettors aren't aided by inside information as sports bettors often are, as my colleague Eric Weiner points out. There are no Pete Roses, Shoeless Joe Jacksons or (for non-Americans) Hansie Cronjes in political betting markets. That leaves them as a convenient measure of conventional wisdom, which will often happen to be right, but nothing more. Are they even a good gauge of conventional wisdom? Silver took to social media on this issue Monday. "Most of what makes political prediction markets dumb is that people assume they have expertise about election forecasting because they a) follow politics and b) understand "data" and "markets," he said. "Without more specific domain knowledge, though, that combo is a recipe for stupidity." He added that the contentions that 1) polls were under-counting "shy Trump voters" and 2) the recent violence would help Trump (made in a much-discussed paper issued Monday by JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategist Marko Kolanovic) provided "an interesting window into the mindset of techbros and financebros who are buying up Trump shares on prediction markets." According to Silver, both these assertions were "almost entirely lacking in evidence, to the point where they're more superstitious than empirical." Kolanovic's argument about violence rests on research into the 1968 election which can be found here. That case has important similarities to today, but also important differences, starting with the fact that a different party is in power. Meanwhile the argument on "shy voters" also appears to rest on one source, which can be found here. Kolanovic may be right, and his arguments appear to me to be more than "superstition" — but Silver is fair in saying that they need far more empirical evidence before we can treat them as being proved. That said, Biden chose Monday to make a strongly worded speech holding Trump responsible for the violence, while Trump spent the day defending violence by his supporters and attacking violence by his opponents. It is obvious that both campaigns see this as critically important terrain — and that they agree with the prediction markets that the events in Kenosha could change the outcome. Whoever wins this argument over the next two months will probably be elected president. The Silence From Stock MarketsMeanwhile, what of the stock markets? Rising uncertainty hasn't damaged them yet. A market this strong at this point in a presidential election year is usually great news for the incumbent party, as shown by this chart from Dan Clifton of Strategas:  When it comes to the overall level, political ructions have so far had no discernible effect. When it comes to Strategas's baskets of companies that stand to be most affected by the election, however, the market still appears to be positioned for a Democratic victory. This chart shows how the stocks that would benefit from a Republican sweep have fared compared to those what would do best under a Democratic sweep, and that it is lagging the Predictit market by about three weeks. Thus, there is a case that over the next three weeks we should expect Republican-benefiting stocks to start to outperform:  But if we look at the action in options, the picture looks different again. The following chart was produced for Bloomberg by the Nobel economics laureate Myron Scholes, now chief investment strategist at Janus Henderson Investors, and Ashwin Alankar, the fund manager's global head of asset allocation and risk management. It measures the the options market's pricing of the upside and downside risk attached to the Strategas baskets. They plotted the options-implied attractiveness of the Democratic stocks relative to the Republican ones. This is measured by "the ratio of upside volatility — or good risk implied by call options — over downside volatility – or bad risk implied by put options." They name this a tail-Sharpe ratio. The higher the number, the better the market implicitly believes Biden's chances to be, while lower numbers are good for Trump:  The chart shows a noticeable tightening of the race in August, but also suggests that by the end of convention season the stock market still viewed the election as a close race with Biden clearly ahead. In other words, their analysis suggests that we may not see the most politically driven stocks move to take account of the moves in the prediction markets over the next few weeks. On balance, these fascinating exercises leave us roughly where we started. People with big money at stake in stock markets, and who are used to assessing political risk, aren't yet feeling it necessary to reposition. That may well change over the next two months, as two candidates have to react to events. Survival TipsMy survival tip today is to ignore the Dow Industrials. I have written about this often in the past, so I will be brief. It is a pointless, methodologically flawed index, whose continued existence is reliant totally on peer pressure and groupthink. It tells you nothing, and the only reason ever to quote it is that other people quote it. The news about the Dow is that three new stocks have been added. The reason was Apple Inc.'s stock split. That split made no difference to the value of Apple, which continues to be the world's biggest company. But it had a profound effect on the Dow which, indefensibly in this day and age, is weighted by share price rather than market value. To quote the press release explaining the change: last month, Apple, the largest-weighted issue in the index, announced a four-for-one stock split, which would effectively change its weight in The Dow from 12.20% to 3.36%, increasing the weight of the other 29 members by 10.1% each and reducing the weight of the Information Technology sector from 27.63% to 20.35%.

Why would anyone care two hoots about an index that can be changed so profoundly by a stock split, and then needs to be frantically reverse-engineered with new members to keep it representative? Obviously there is some charm in the historical continuity represented by the Dow. It would be a shame to discontinue it. So I have this humble proposal: Remove all the current 30 members, and replace them with a 100% weighting to "SPY," the exchange-traded fund that tracks the S&P 500. That way people who habitually check the Dow will have a more meaningful index to follow, and its historical record can continue unbroken. How about it? Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment