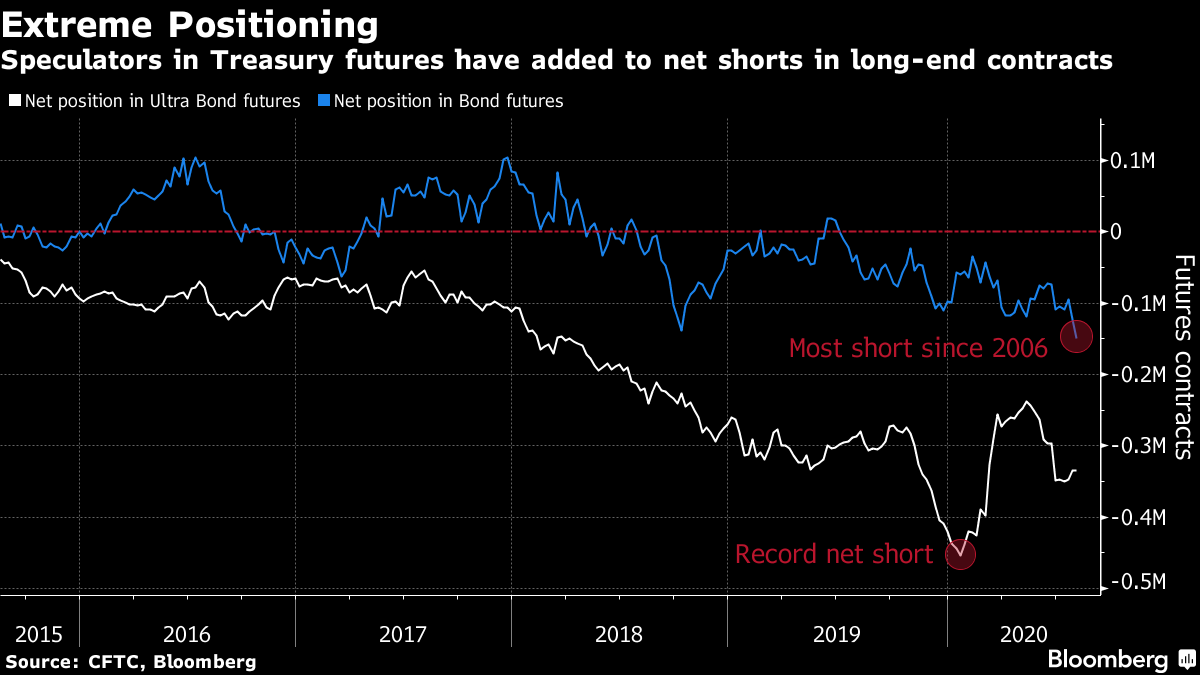

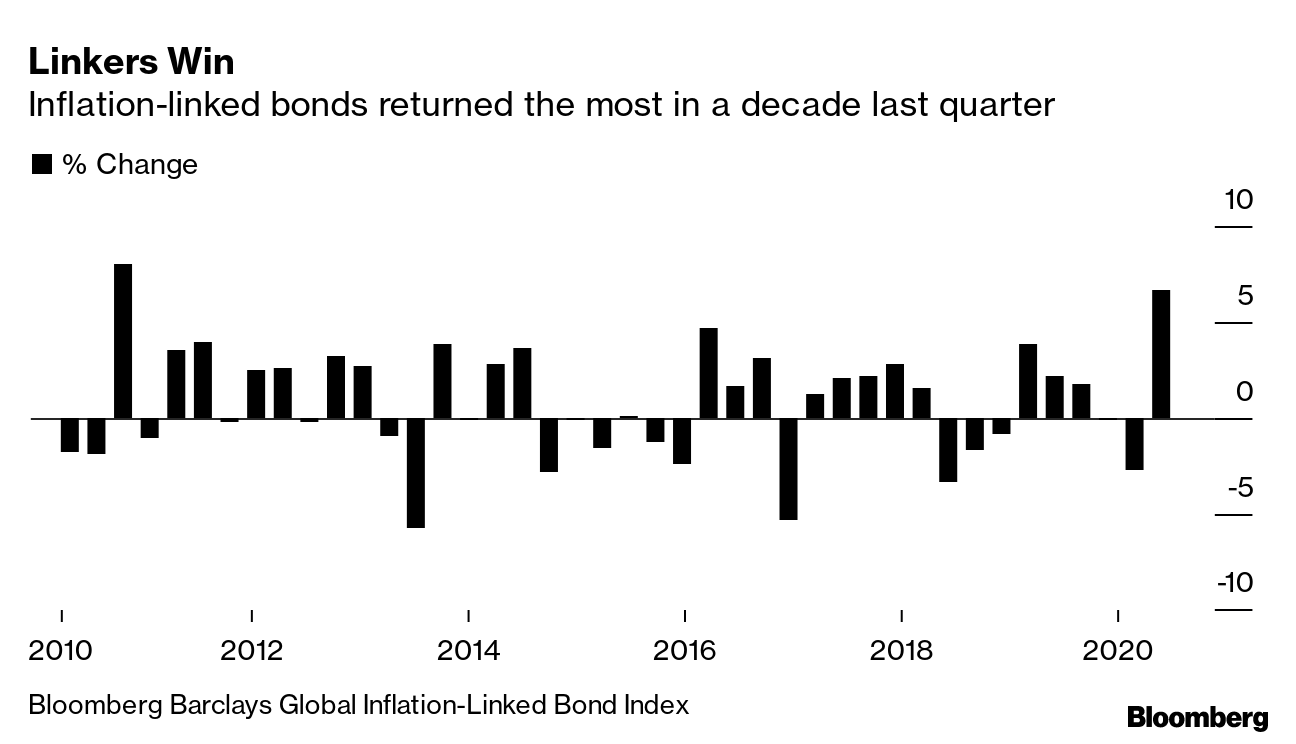

Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that isn't sure if negative real yields exist metaphysically. –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter. A little indigestionThe biggest bond market in the world made some folks nervous this week. The jitters stemmed from the Treasury's latest round of record sales, but the concerns stopped short of being a rallying cry for bond vigilantes. The 10-year note fell, taking yields to the highest level since around mid-June. Still, that's a pretty modest repricing for the month of August, when markets can run amok during vacation season. And it came in the midst of three of the largest Treasury auctions in history.  A quick look at those auctions. The three- and 10-year note sales this week proceeded with no trouble -- it wasn't until Thursday's $26 billion offer of 30-year bonds that things got a bit messy. Expectations for participation might have been running a tad high after the success of last month's ultra-long sale. That was smaller, and drew a record share of indirect bids, suggesting that cheaper hedging costs were reeling in significantly more foreign buyers than is typical for this maturity. They weren't quite so keen on the latest auction, since the dollar has stabilized. Still, at 1.41%, the rate on this bond was less than 0.1 percentage point off the all-time low set in March. "The problem here is that the Fed is not going anywhere and inflation is miles away from 2%, but volatility in long-end rates is so low that every pop brings forward speculation that the narrative is changing," said Columbia Threadneedle senior analyst Ed Al-Hussainy. The Treasury's counterfactual loss was the steepener trade's gain. Predicting the curve's moves has been a mug's game this year, but investors expecting long-end yields to rise further above the short end were rewarded this week, after a trying couple of months. The gap between the five- and 30-year yields stretched to 112 basis points, the widest since early July.  Where the market goes from here may come down to the fate of some stretched positioning. This week's move tallies with increasingly heavy wagers on higher rates at the furthest end of the Treasury curve. Rates reporter Ed Bolingbroke this week spotted a surge in open interest in ultra-long futures coinciding with the jump in yields. New shorts will have added to already-crowded positioning, judging by the hefty tally of negative bets on long-end bonds shown in the latest data from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. A trade this stretched could mean an eye-watering snap back for Treasury bears, but that may well be deferred until after the Treasury's $25 billion offer of 20-year bonds Wednesday.  Ian Burdette, head of term trading at Academy Securities, is one of those bears, and he reckons the numbers are on his side, since the Treasury put its borrowing needs north of $2 trillion in the second half of the year. At the outset of the pandemic crisis, he said, global markets were overwhelmed by the coordinated central bank response, but now "the fiscal financing side is coming on line." He's not anticipating a "vicious" rebound in yields, but 2% on the 30-year is within reach. The real issue A standout feature of this week's Treasury market selloff, which may also have buffeted parts of the equities and commodities worlds, was the climb in real yields. It's strange to be talking about an increase, since the 10-year inflation-adjusted rate was recently at an historic low, amid a miserable growth outlook and faith in the Fed's ultra-easy policy stance. The Fed is widely expected to formalize its commitment to keeping interest rates floored at its next meeting. And it's hard to argue that the economic picture has brightened much. The pandemic is on a collision course with the U.S. flu season. Jobless numbers have clearly improved, but unemployment is still in double digits, and the better-than-feared data may simply have eased pressure on lawmakers to come together on a fiscal plan quickly. There is still no sign of an agreement on further stimulus. So it seems real yields are rising, like nominals, on the flood of supply. It's clear from the chart below that both rates turned higher at the end of last week, ahead of yet another record week of Treasury sales.  But not everyone is ready to dismiss the more-optimistic reflation story that until a week ago was propelling gains in stocks and gold, not to mention pummeling the U.S. dollar. "A one-dimensional analysis of supply and interest rates fails to pass the sniff test, there's plenty of other stuff going on as well," said Guy LeBas, chief fixed income strategist at Janney Montgomery Scott. "The reflation trade is still on the horizon, and the Fed is the enabler." After all, a larger-than-expected gain in U.S. payrolls earlier in August provided a cue for Treasury fans to exit, pursued by bears (to borrow from a more-famous but equally convenient plot device). There's also the possibility of progress in tackling the virus. JPMorgan strategists have observed that the 5- to 30-year Treasury curve is "loosely correlated" to an indicator they created to track the ratios of positive virus tests across the U.S., and they reckon "bonds seem to be responding to the improving COVID trends." And last month's core consumer price inflation reading -- which strips out food and energy prices -- jumped by the most in almost three decades. That helped boost the market's outlook for inflation, reflected in breakevens. Which leads us to the question that continues to vex and divide investors. What's up with inflation?It's higher than it was. So are market expectations, given the many trillions of dollars poured into the financial system to avert a deeper crisis. That doesn't mean we're about to be swept up in an inflationary spiral. The reflation trade has done well -- the Bloomberg Barclays Global Inflation-Linked Government Index turned in its best performance in a decade in the second quarter. Investors in linkers have profited in large part because they picked up cheap hedges against rising price pressures.  The path of inflation from here is trickier. To be sure, the latest consumer price inflation numbers were stronger, but the Fed's preferred measure -- personal consumption expenditure -- is just 0.8%. The 10-year breakeven rate is the highest since January, but that level is still just 1.7%, and shy of the Fed's 2% target. And if you convert that market gauge to PCE, it's an even bigger undershoot, at around 1.4%. Moreover, breakevens themselves aren't entirely dictated by the market's inflation views. Since the Fed's massive interventions, they may have been saying more about its grip on nominal rates, according to Bank of America's Bruno Braizinha and Olivia Lima. While the central bank has been suppressing Treasury yields, real yields by contrast have more flexibility to reflect the economic landscape -- it's close to historic lows now just above minus 1%. That may mean the gap between the two is less useful as a guide to inflation than it has been in the past. All that being said, next week might bring more fodder for the reflationistas, with the release of the minutes from the last meeting of the Federal Reserve's Open Market Committee. That's expected to offer a little more insight into the strategic review that's close to wrapping up, and which is expected to make policy makers more willing to tolerate an overshoot of their inflation target -- implying lower rates for as long as it takes. Over in New ZealandSpeaking of inflation targeting, we turn to the country that pioneered it. In the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, New Zealand stood out by flattening its curve and wrestling its cases down, although it's now facing some new infections. It's clear New Zealand's policy makers are fully mobilized, with Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr declaring this week that the bank aims to push yields lower by expanding and extending a quantitative easing program. Policy makers held the official cash rate at a record-low 0.25% on Wednesday and included negative rates in a tool kit they're keeping in "active preparation." Swaps traders are pricing in a cut below zero by July next year. This ought to be a boon for New Zealand's bonds, which don't correlate closely with Treasuries and so have a better chance than most of weathering any tremors in the U.S. market, says our Markets Live blogger Wes Goodman. They've been outperforming their Aussie peers for the past month, with the New Zealand 10-year yield rallying to 0.7% from 1%. Bonus PointsThe latest tech giant taking a bite of the cheap-money apple Listen: The ECB's former Vice-President explains Europe's historic step The Fed appears to be fretting about zombie companies Catskills town is feeling the pressure of a New York exodus Here's what the post-Libor world will look like Killer Mike wants to save disappearing Black banks Portnoy gets some Winkelvii learning Did you miss World Elephant Day? |

Post a Comment