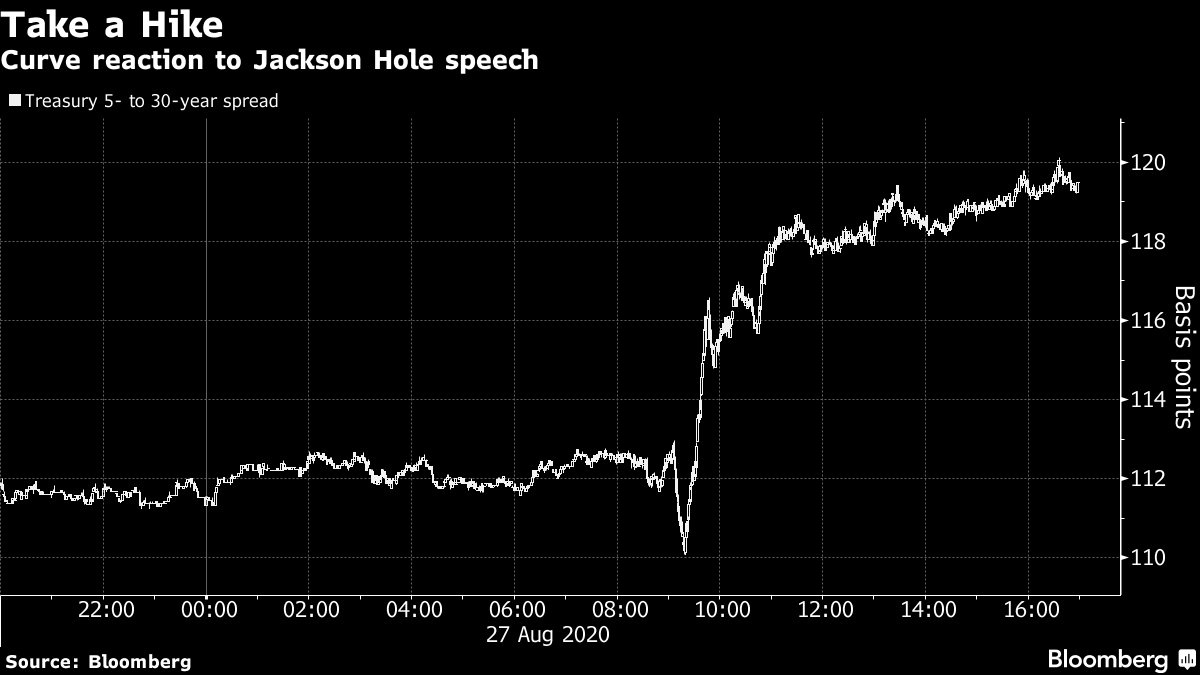

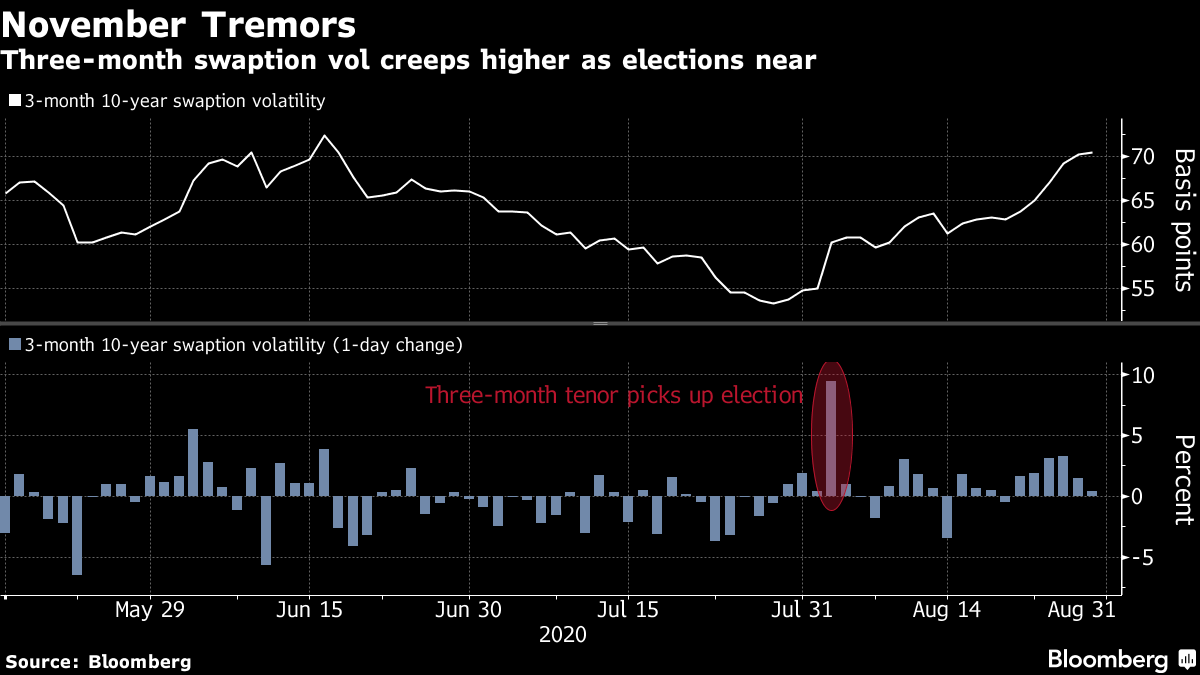

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that suspects markets might be pinning a few too many hopes on the September Fed meeting. –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter. Action Jackson In years to come, one of the most memorable features of this year's Jackson Hole conference will be the fact it was virtual. The meeting opened Thursday, but with none of the cinematic backdrop that sometimes upstaged earlier iterations. The venue -- Jackson Lake Lodge in the Grand Teton National Park -- was closed due to the pandemic. Chairman Jerome Powell's opening speech memorialized an important shift for the Fed, and how the market is to understand its behavior. Just ahead of Powell's address, the Fed published a revised statement of its longer-run goals -- the fruits of two years' labor to better meet its mandate. The Fed now aims for 2% inflation on average over time. That means policy makers will be more willing to tolerate an overshoot and, importantly, to allow unemployment to drop below levels previously considered inflationary, without triggering rate hikes. Or, to put it another way, it's a bit like throwing the Taylor Rule "in a dumpster," as Bloomberg Opinion's Tim Duy deftly put it. But to be honest the only really surprising thing about the unveiling was that it came a bit sooner than expected. The changes had in some ways been well telegraphed. So why did long-dated U.S. Treasury yields hit their highest levels in more than two months? One factor is that nominal yields are now just catching up with the longer-term rise in breakeven rates, which has taken the market-implied rate for consumer-price inflation over the next decade to 1.76%, from less than 0.5% in March. We saw this week an extremely dovish shift in mindset for the Fed, according to Michael de Pass, global head of U.S. Treasury trading at Citadel Securities, as it's willing to let the economy run hotter until inflation actually shows up. "This tells you it is extremely unlikely that the Fed would preemptively raise interest rates because of a strong labor market where inflationary pressures aren't above 2%. That is a significant change from where we were historically." Under this regime, the last tightening cycle of nine hikes from 2015 through 2018 certainly wouldn't have started as soon as it did. It may not be a hugely relevant shift while unemployment's still around 10%, de Pass added, but "it's a green light for steepeners over the near term."  Second, investors just might have been nursing hopes of a stronger sign of further stimulus, or at least confirmation that the Fed may soon tweak its $80 billion a month asset purchases to focus more on longer-dated securities. That prospect had been raised by Governor Lael Brainard, who speaks on the economic outlook Tuesday. Third, the market's dealing with a fair bit of fuzziness at this point. The Fed is clearly keeping its options open -- as if, having finally unshackled itself from the Phillips Curve, it's not about to submit to a host of other metrics. "Our decisions about appropriate monetary policy will continue to reflect a broad array of considerations and will not be dictated by any formula," Powell said. Barclays took this as a bearish cue: "lingering uncertainty about the precise path of policy should result in higher term premium." Strategists reaffirmed their short position on the 20-year bond. Of course, the Fed may be more forthcoming with specifics in September -- primary dealers expect fresh forward guidance at this meeting, according to the Fed's July survey. The minutes from last month suggest policy makers were divided over using economic data or a timeline -- or both -- to guide the market's expectations. But, as many Fed watchers have pointed out, the Fed doesn't have to do anything just yet. The market isn't fighting it -- rates are priced to stay low for years to come. "A pivot to explicit forward guidance still seems a little premature, even with the framework review being announced sooner than expected," wrote NatWest economist Kevin Cummins. He's looking for fresh forward guidance at the Nov. 4-5 meeting -- a couple of days after the U.S. presidential election. The U.S. Election Is Nigh The national conventions are done, so 'tis the season. Though you wouldn't know it given the lack of balloons. It's a mug's game, predicting the market impact of an election. Exhibit A is the surprise victory of President Donald J. Trump in 2016. The stock market rapidly digested the implications of promised tax cuts and deregulation and marched higher, flouting the somber predictions of the few who'd bothered to contemplate such a turn of events. That last doozy hasn't prevented Wall Street from churning out note upon note about the implications of a Trump win, a Biden win or a blue wave. And when it comes to the bond market, they tend to couch their views in what these scenarios mean for the central bank, which is by far the strongest hand in what happens to interest rates. Like most, Bank of America has streamlined its scenario analysis by jettisoning the quaint notion of bipartisanship, and considering the upshot of gridlock versus a sweep of both houses. Gridlock implies limited fiscal stimulus, meaning the Fed "could become significantly more engaged with yield curve control or larger QE purchases, or purchases further out the curve -- or all of these" to offset the government's reduced appetite for spending, according to Ralph Axel. That could mean much wider long-end spreads. The case for tighter spreads would be a Democratic sweep, implying a bigger fiscal response with less action from the Fed. While they're leaning toward the tighter scenario, "the risk/reward has turned less favorable with the recent fiscal impasse, which not only threatens less Treasury supply, but substantially larger Fed QE." For its part, Goldman is looking at rates market conditions rather than the outcome. They suspect this year's event could be more than usually tumultuous, and while a jump in volatility is now detectable in the three-month swaptions spanning election night, the market may be too complacent about the weeks after. The market isn't yet reflecting the more prolonged ructions that typically come with a switching in the governing party, or a clean sweep of Congress, according to rates strategist William Marshall. Moreover, thanks to the Fed having anchored the front end of the Treasury curve, he reckons any volatility is likely to hit the 5-to-10-year stretch more than the 2-to-10 year that's typically taken the brunt.  Twist in India's Tale The one silver lining for parts of the developing world in this pandemic-stricken global economy has been some newfound flexibility to ease policy. In Asia, the U.S. dollar's weakness has helped stem capital flight, allowing local currencies to strengthen, curbing inflationary pressure. Against this backdrop, Indonesia has made a foray into monetizing its debt. This week, India's markets showed the limitations of this flexibility, demanding more than the central bank can hope to deliver in an economy threatened with stagflation. The Reserve Bank of India finally resolved the "will they, won't they" debate over its plans to further support the debt market, with a Twist. After two poorly-received sales of longer-dated government debt, the central bank said it will purchase 100 billion rupees ($1.4 billion) of bonds and sell an equivalent amount of shorter debt in an exercise that started Thursday. The move -- which is similar to the Fed's Operation Twist from 2011-12 -- is the third since April. At their August 4-6 meeting, policy makers resisted further easing in light of rising inflation, preferring instead to see how a spate of rate cuts over the past 18 months would seep into an economy that's been ravaged by curbs to fight the virus. Covid-19 infections are still surging, with more than 3.3 million confirmed cases. The bond market faces a record 12 trillion rupees of supply this fiscal year. Yet the central bank's announcement only briefly checked a further climb in yields, our Kartik Goyal reported. The market is looking for a more regular commitment, says Ritesh Bhusari, deputy general manager for treasury at South Indian Bank, perhaps via weekly open market operations. Without further measures, he reckons benchmark yields could reach 6.40% in the coming weeks. The 10-year touched 6.20% this week, up almost 40 basis points since the start of August.  The broader fear in the market is that the RBI's easing cycle is running out of road. Consumer-price inflation came close to 7% in July, and the central bank's own survey sees an acceleration to double-digits in three months. And while this year's economic contraction is proving tough to measure in the midst of an aggressive lockdown, it's considered possibly the worst since at least the global recession of the 1980s. Bonus Points THIS is how you announce a symmetric inflation target (h/t Julia Coronado) There is $1 trillion stashed away in the U.S., and it just might save the economy. This keeps showing up on my Twitter feed, so I'll just put it right here. The Covid bankruptcies keep piling up What might a vaccine do to markets? Redlining etched in the heatmaps of American cities Don't miss True Grit: The online book club |

Post a Comment