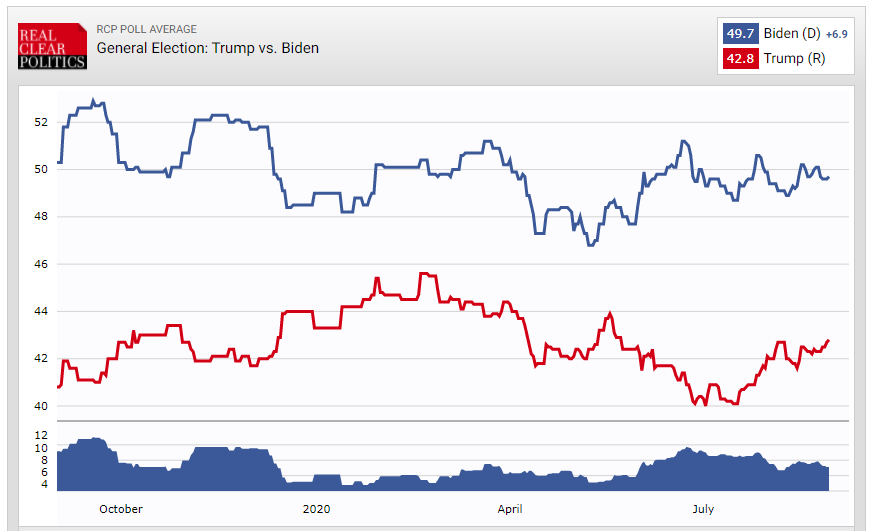

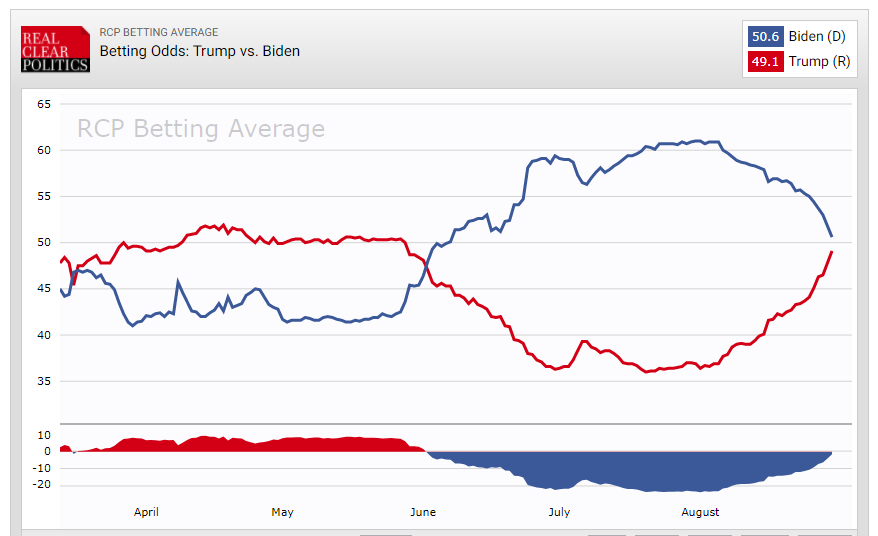

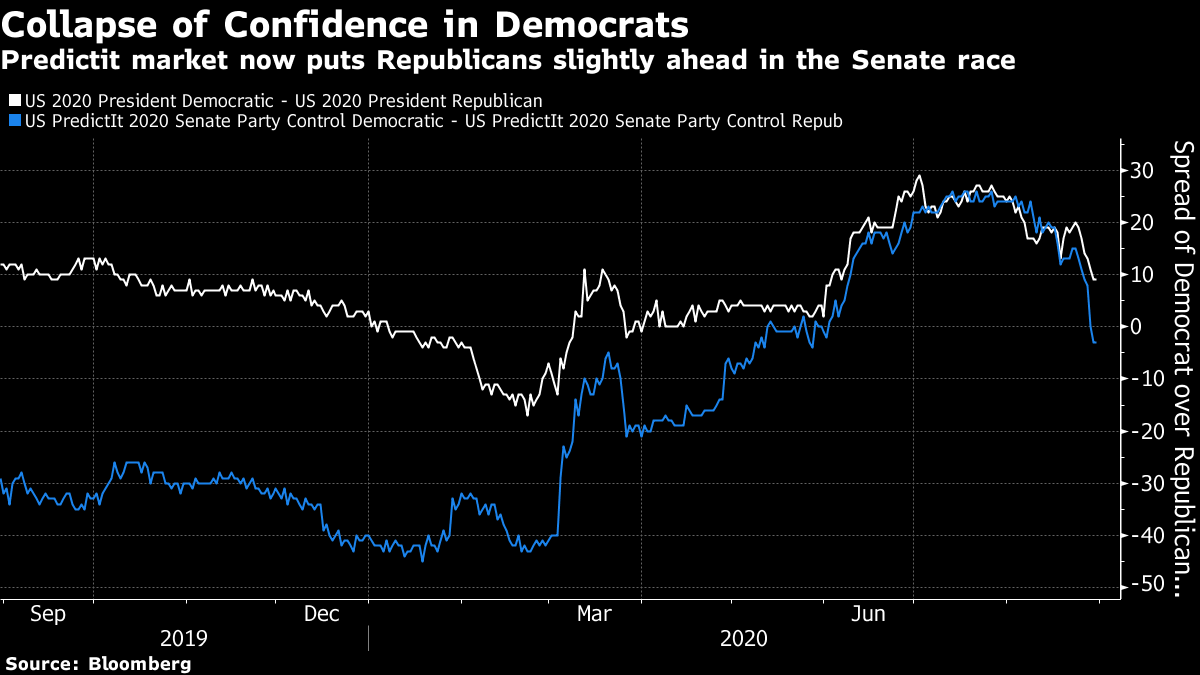

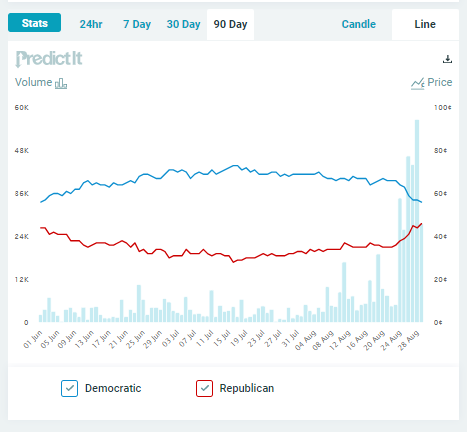

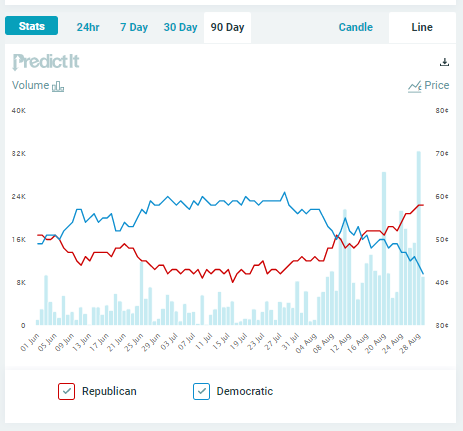

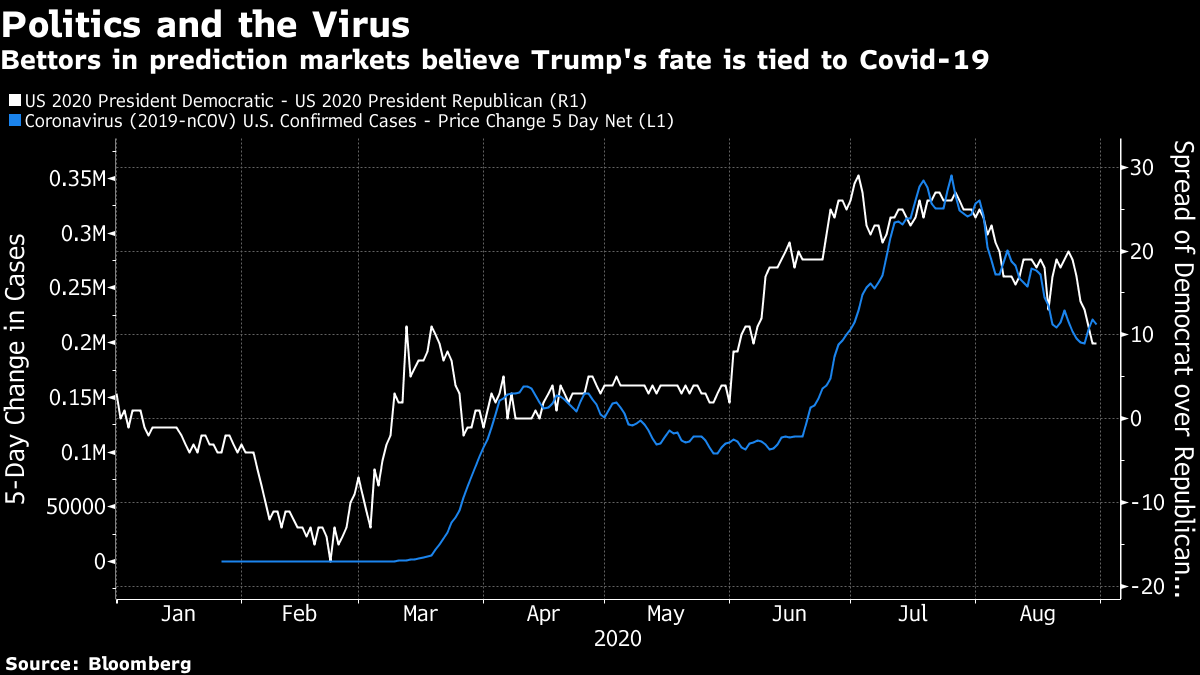

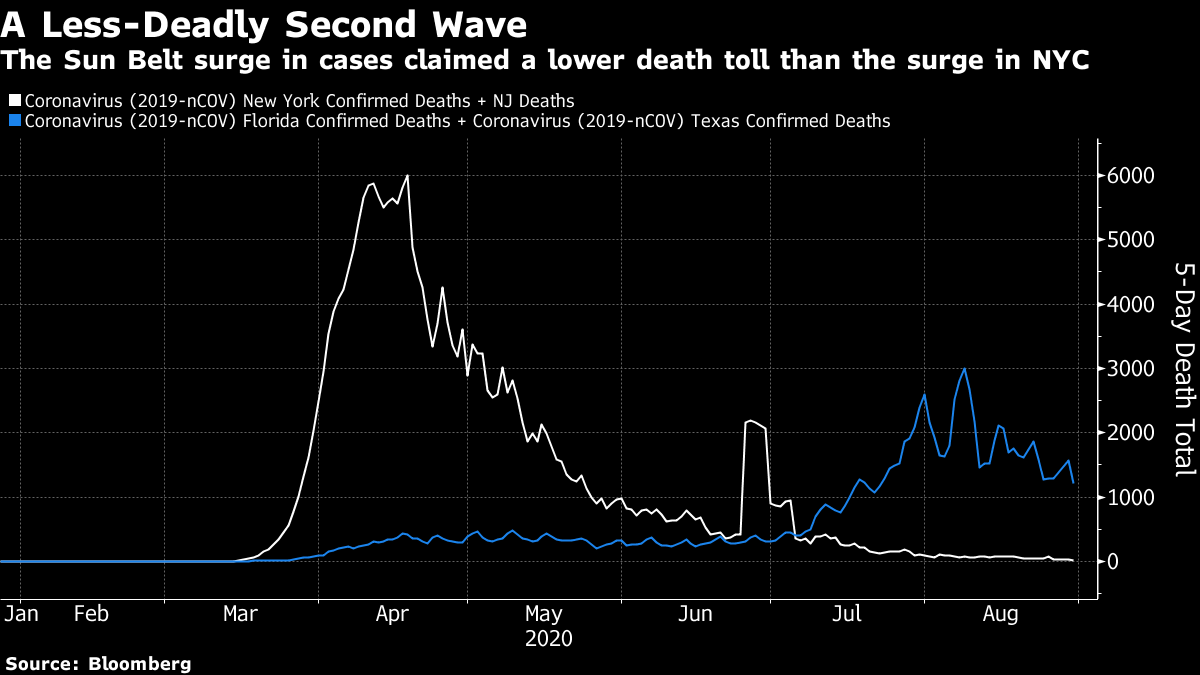

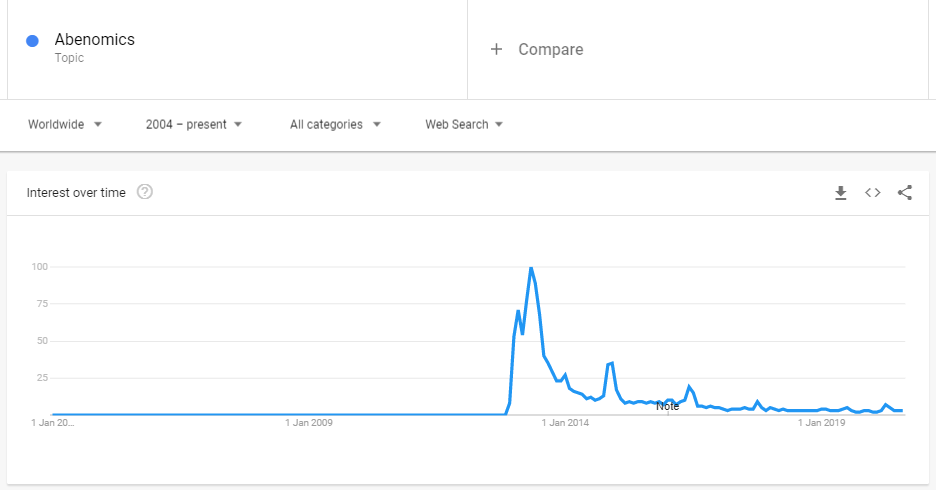

Prediction Markets vs PollstersLabor Day will be late this year, on Sept. 7, and it barely seems to function as the start of the presidential campaign any more. With both parties' conventions complete, the last leg of the U.S. presidential campaign starts now. It does so with prediction markets, in which investors trade futures tied to the result, suddenly sharply out of line with the closest political equivalent of "fundamentals" — rolling poll of polls averages. The following chart of the polling average from RealClearPolitics shows the Democrats' Joe Biden in a clear and stable lead of almost 7 percentage points:  Now look at the "betting average" compiled by the same organization. This aggregates a number of spread-betting sites to produce an average probability of each candidate winning. On this reckoning, Biden's lead has collapsed in the last month:  In the Predictit market, where investors trade futures tied to political outcomes, the spread on Biden beating Trump has declined sharply, but is still at 10% (55% plays 45%). What will be horrifying to Democrats is that their chance of taking control of the Senate is deemed to have imploded:  Neither prediction markets nor polls are perfect. They were both wrong four years ago. But it's hard to get a better grasp on perceived probabilities than from a prediction market, where people are betting actual money. Over history their results have tended to be uncannily accurate. And polls tend at least to be directionally right. There are, I suspect, three factors at work here. The first is simply a lag. Gamblers have the chance to place bets before the polls come out, and a lot of people are convinced that the odds have shifted in the Republicans' favor. This will be partly due to the Republicans' convention, which would normally give some polling "bounce," but is more thanks to a second critical factor, which is the disorder in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Since the shooting of Jacob Blake went viral a week ago, trading volume in Predictit's contract on the presidential outcome in Wisconsin has surged, as has the probability of a Trump victory. Biden is still shown with a slight lead, but it has reduced sharply — and Wisconsin may well be the "tipping point" state that decides the election.  The Kenosha effect isn't specific to Wisconsin. Bettors appear to believe that the disorder will help Trump throughout the country. Here is a similar chart for North Carolina, a state that fell to Barack Obama and which bettors considered a likely Biden victory. There has been a dramatic change, which started before Kenosha and has since accelerated:  Are prediction markets right? In 1968, perceptions of increasing lawlessness helped Richard Nixon to victory — but he was running against a sitting vice-president, while the current Republican candidates are incumbents. There is also a strange disconnect in the betting markets, which is that the violence following the killing of George Floyd in late May, and the growth in support for Black Lives Matter, was seen as almost wholly positive for Biden, while the latest protests are seen as helping Trump. There should be more evidence on the Kenosha impact in coming days. For now, the caution of fivethirtyeight.com makes sense: "There's just not a lot of data that can help us understand how Americans are responding to what's happening in Kenosha, Wisconsin, but… one thing we do know is that declining support for the Black Lives Matter movement hasn't translated to a decline in support for Biden just yet." The final factor is the coronavirus. So far this year, Biden's chances have improved when cases are increasing, and declined when they are falling. The relationship is startlingly close:  If cases continue to decline, Trump's chances will be deemed to improve further. Moreover, there is evidence that the virus is less deadly as time goes by. The fact that the (mostly Republican) Sun Belt states suffered far fewer deaths than the (mostly Democratic) northeast did earlier this year is seen as removing a key risk for Trump. The following chart compares the five-day change in deaths for New York and New Jersey, against Florida and Texas. It shows that the second "wave" in the sun belt was far less severe — and would seem even smaller if the numbers were adjusted to take account of the southern states' larger populations:  Republicans tended to refer to the pandemic in the past tense at their convention last week, which was highly questionable given the continuing numbers of fatalities. But if current trends in infections and deaths continue, it may begin to look justifiable by election day. Will it happen? Two months ago, I offered this framework for asking why infection rates (often referred to as "R") were falling. It was produced by Andrew Brigden, chief economist of Fathom Financial Consulting in London, and it remains as relevant today. He offered five roughly equally plausible explanations: - Heterogeneity across the population means that we all have a different R number, with some people, including those with a large network of contacts, more likely both to acquire the disease and to pass it on. Once those people have been exposed, and are no longer susceptible, the average R will fall;

- The virus has spread far more rapidly than antibody testing suggests, which means the virus is running out of people to infect;

- Fear of dying from the disease provokes other changes in behavior, such as more frequent hand-washing and wearing face masks;

- Potential "super spreader" events — such as nightclubs and concerts that bring many people together indoors — are no longer happening;

- It is a seasonal phenomenon in the northern hemisphere, and will return later this year.

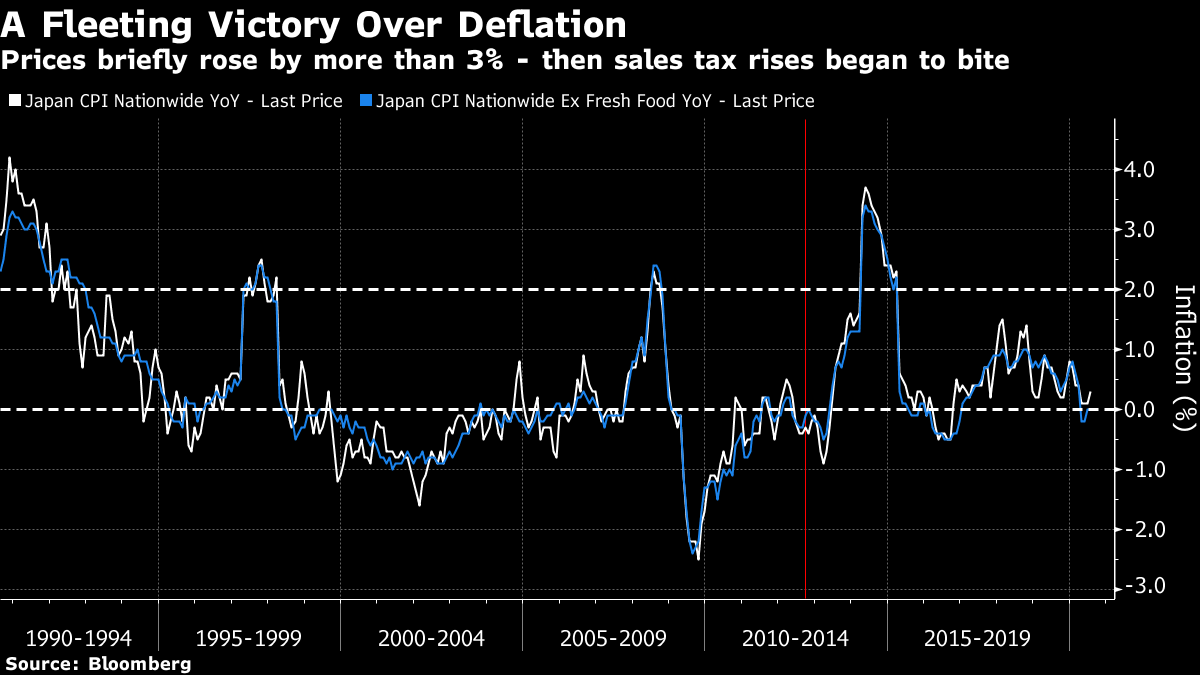

The first two are broadly cases for "herd immunity" having arrived earlier than many had expected. If true, these would be great for Trump. The third and fourth suggest there could be perils from complacency, particularly as schools attempt to reopen. The fifth would be a disaster, but there is no particular evidence yet that it is going to happen. If, looking through these options, bettors think the pandemic may appear to be over by November, then that would go a long way to explaining the way they see the race narrowing. Whatever the truth of the coronavirus, it would be wise to brace for a lot of politically induced volatility between now and the end of the year. Sayonara AbenomicsEver so quietly, one of the most consistent and important players in global politics of the last decade is about to stand down. And it looks as though Warren Buffett has given him an immense seal of approval just as he leaves. Shinzo Abe's big achievement when he became Japan's premier for the second time in late 2012 was to return the country to relevance. He ended a leadership carousel that had seen six leaders come and go in as many years (including Abe himself), and he persuaded the world that "Abenomics" would jolt Japan out of its decades-long deflationary dynamics. He always had his doubters. Christopher Eoyang, Goldman Sachs Group Inc.'s chief growth markets strategist at the time, recommended shorting Japan, saying the only risk would be that "the Japanese actually follow through on something they've never done before." As the following Google Trends chart shows, Abenomics captured great interest in 2013 and 2014. Without being abandoned, it has steadily dwindled in interest ever since:  Why? The critical reason is that Abenomics is perceived outside Japan to have failed in its single most important mission: generating inflation. The advent of Abe and the exceptionally aggressive monetary policies of Haruhiko Kuroda's Bank of Japan (which pioneered yield curve control and buying exchange-traded funds) briefly took the headline inflation rate above 3%. But lenient monetary policy was balanced by tight fiscal policy, as the government imposed a sales tax increase. That soon snuffed out inflation:  The stock market did well for Japanese domestic investors, but only if they didn't mind missing out on greater profits overseas. Relative to the rest of the world, the Topix sharply outperformed in common currency terms at first, but before long Japanese stocks resumed their long trend of underperformance.  This was primarily driven by valuation, rather than corporate performance. By multiples of book value and sales, Japanese stocks' discount compared to the S&P 500 narrowed a bit in the early years of Abenomics, only to widen again.  Where Abenomics had a galvanic effect was on the currency. He tanked it, and this is just what Japan needed. On a trade-weighted basis, the currency shot downward, making life far easier for Japan's exporters.  What effect will Abe's resignation have on Japan and its markets? The political uncertainty should be resolved by the middle of next month. A number of different candidates are already jockeying for position. Any direct market effect could be seen in a strengthening of the yen, which does counterintuitively well at times of uncertainty, even when Japan is itself the source. Uncertainty will be limited by the fact that Kuroda will stay at the BOJ for another two years. As far as investors are concerned, change is limited for a while. As for a more lasting legacy, Japan has plainly benefited from the years of stability. My colleague Noah Smith looks at Abe's political legacy here. Abe also recognized his own mistakes, with legislation passed last year that will thwart any further rise in sales tax for a decade. The shock of his resignation caused a sharp fall Friday that was swiftly reversed Monday morning:  Meanwhile, the lasting reputation of Abenomics may be helped by the unlikely figure of Buffett, who announced Monday that he had built up 5% stakes in all five of the country's trading houses at a cost of some $6 billion. If Buffett perceives an undervalued asset in Japan, that suggests something has changed. Jesper Koll, the veteran Tokyo investment banker who is now the CEO of WisdomTree Investments Inc., says the trading houses will give Buffett a great inflation hedge (because soft and hard commodities drive their stock prices), while also providing a hedge against a further deterioration in U.S.-Chinese relations. As global companies stop buying Chinese parts and suppliers, they will in many cases switch to Japanese ones. There is a final point where Buffett may perceive a success for Abenomics. There were always supposed to be "three arrows" to his economic plan. After monetary and fiscal policy, the third focused on reforms to improve corporate governance and stimulate innovation. Japanese companies have acted as value traps for so long in large part because foreign investors find that they have no way to force change. Now, Koll points out, Buffett is buying into a potential bonus from improved corporate governance. The trading houses have functioned as effective venture capitalists, backing successful startups. If Abenomics has finally succeeded in shifting the corporate culture enough to convince Buffett, its greatest successes might lie ahead. Survival TipsThere is at least one part of life that is actually improved social distancing: visiting museums. New York's Museum of Metropolitan Art reopened last week. Tickets are limited to avoid overcrowding, and must be purchased in advance. Normally, the Met is so big as to be overwhelming and can get as overcrowded as the New York subway at rush hour. Last week, we could spend hours there, enjoying peaceful unobstructed views. I particularly enjoyed the Met's special exhibition on the art of the Sahel, the great empires that once flourished on the southern border of the Sahara. With so few people there you could even enjoy listening to the West African music the museum was playing. So here is Tulumba, my favorite song by my favorite West African musician, the late, great Ali Farka Toure. Have a great week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment