The Golden ConstantGold is still glittering. The shiny metal has reversed slightly in recent days, but its upward trend remains uninterrupted. It tends to move directly in line with real yields (those on inflation-linked bonds, or the result of subtracting the breakeven inflation forecast from the nominal yield). While gold is only just below the all-time high of more than $2,000 per ounce set earlier this month, real 10-year Treasury yields are only a little above the all-time trough of minus 1% also reached earlier this month:  This isn't a coincidence. Plainly, the phenomena are linked. And it makes sense for gold to be guided by real yields. The metal pays no income. It follows that its appeal will be greater as real yields fall. When they are negative, as now, we should expect gold to be historically expensive. Nicholas Johnson of Pacific Investment Management Co. sets out the classic methodology for valuing gold like a bond in a post for the Pimco blog: Since about 2006, gold has traded like an asset with nearly 30 years' real duration (meaning that a 100-basis-point move lower in U.S. Treasury real yields has translated to a roughly 30% increase in the price of gold). From a market perspective, as real yields on U.S. government bonds rise, one would expect investors to marginally prefer those assets, moving out of gold and into U.S. Treasuries and Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). Gold prices should drop in the process. Conversely, when Treasury real yields fall, gold prices would tend to climb.

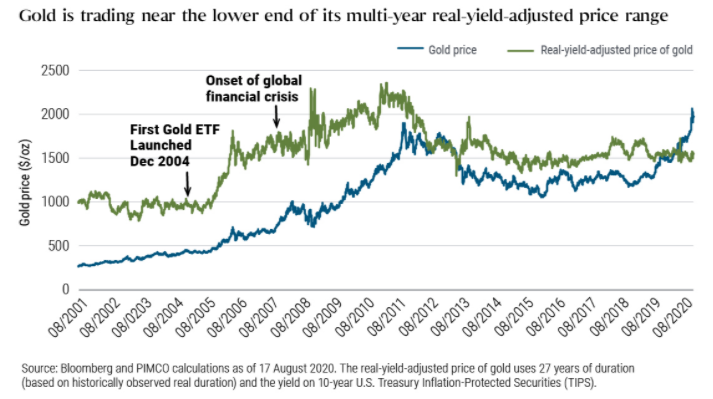

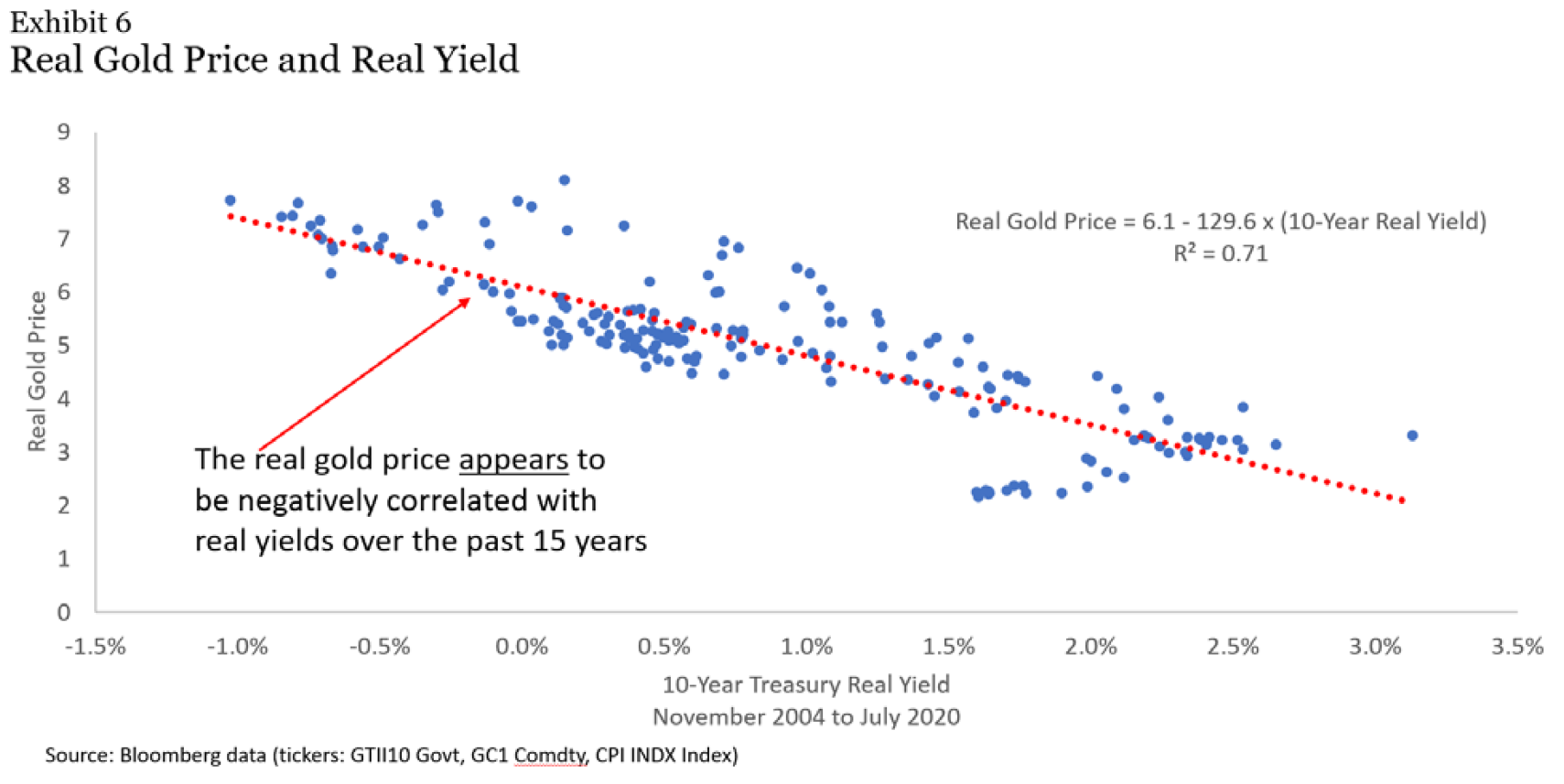

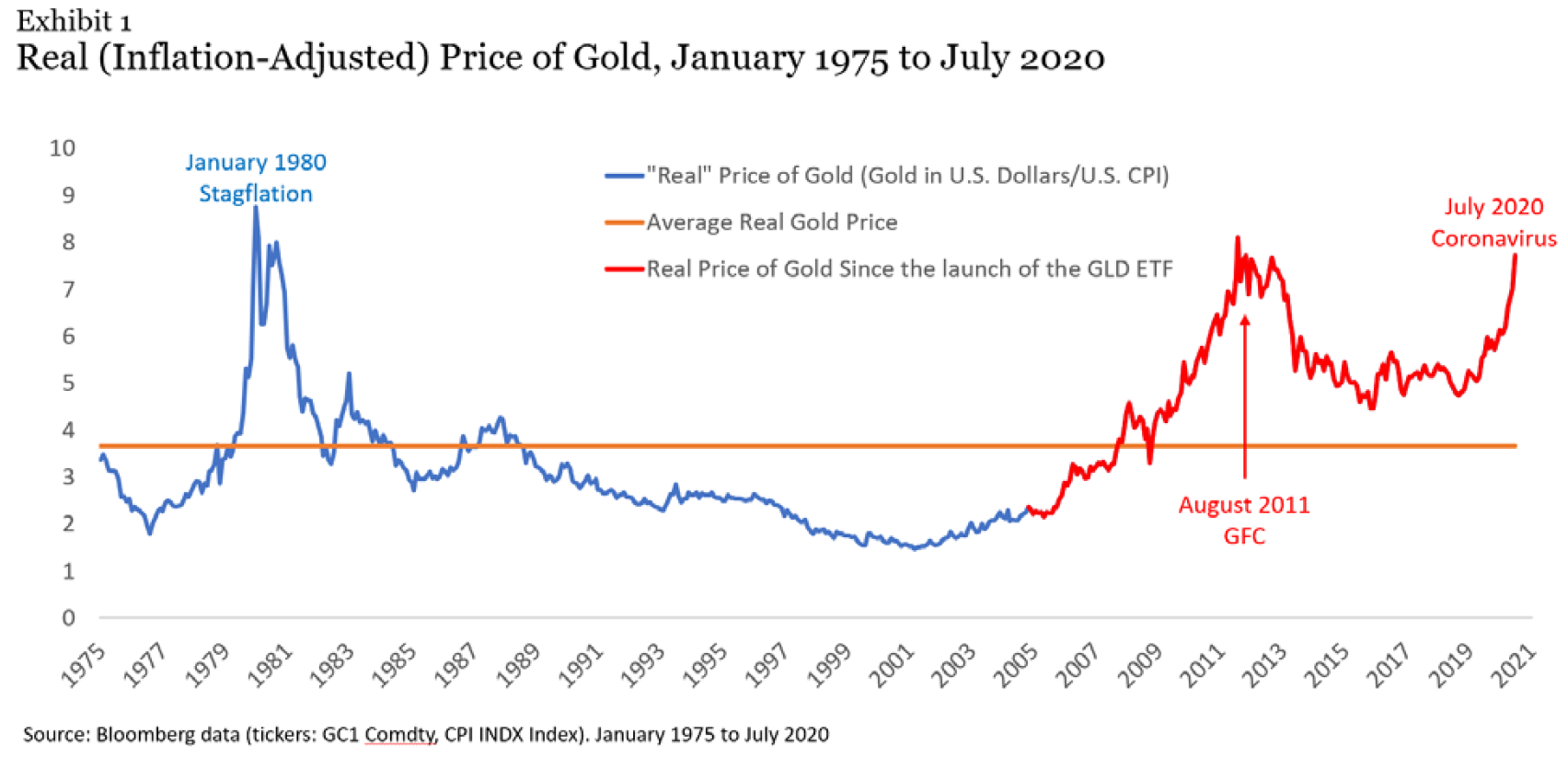

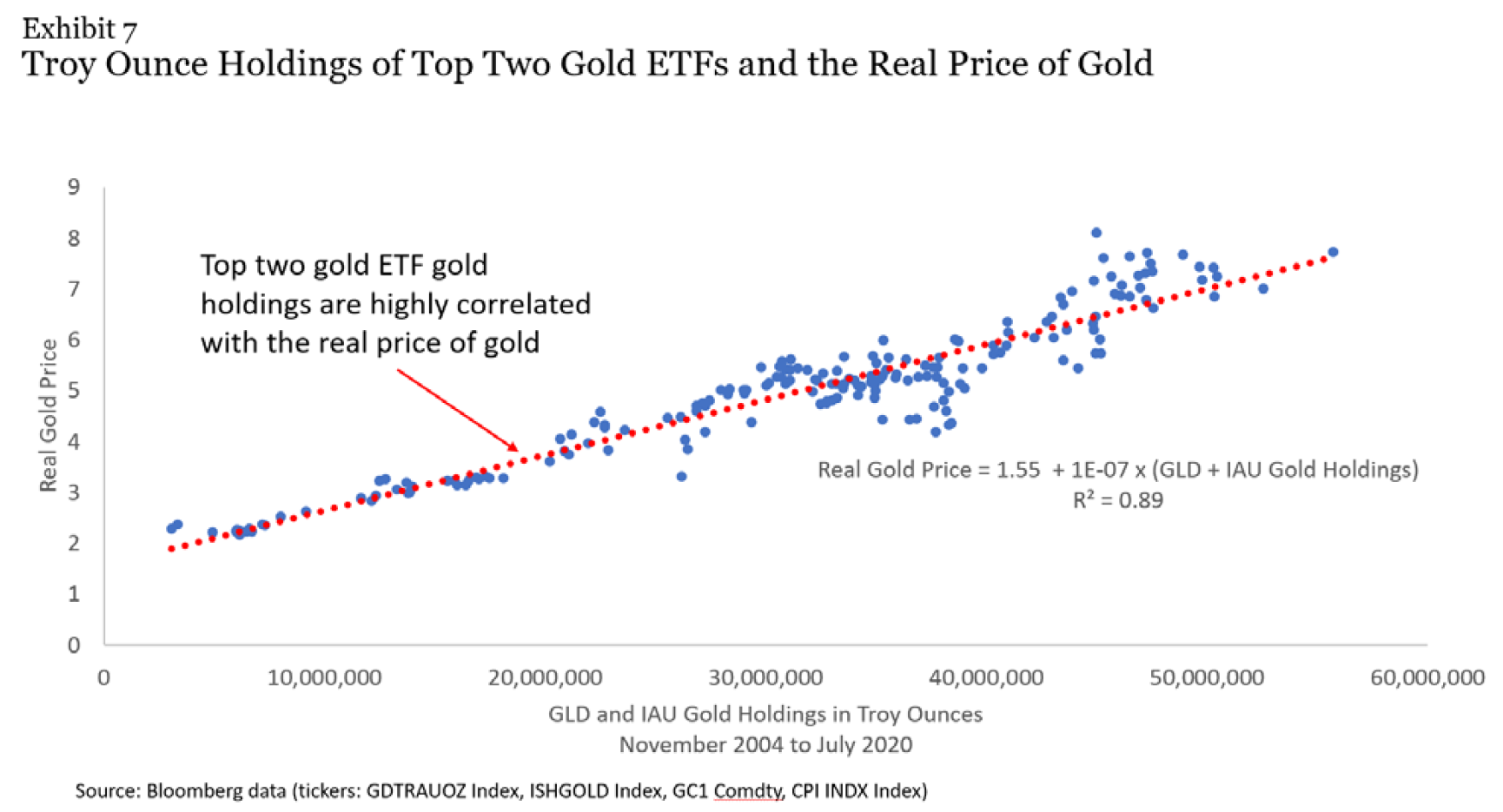

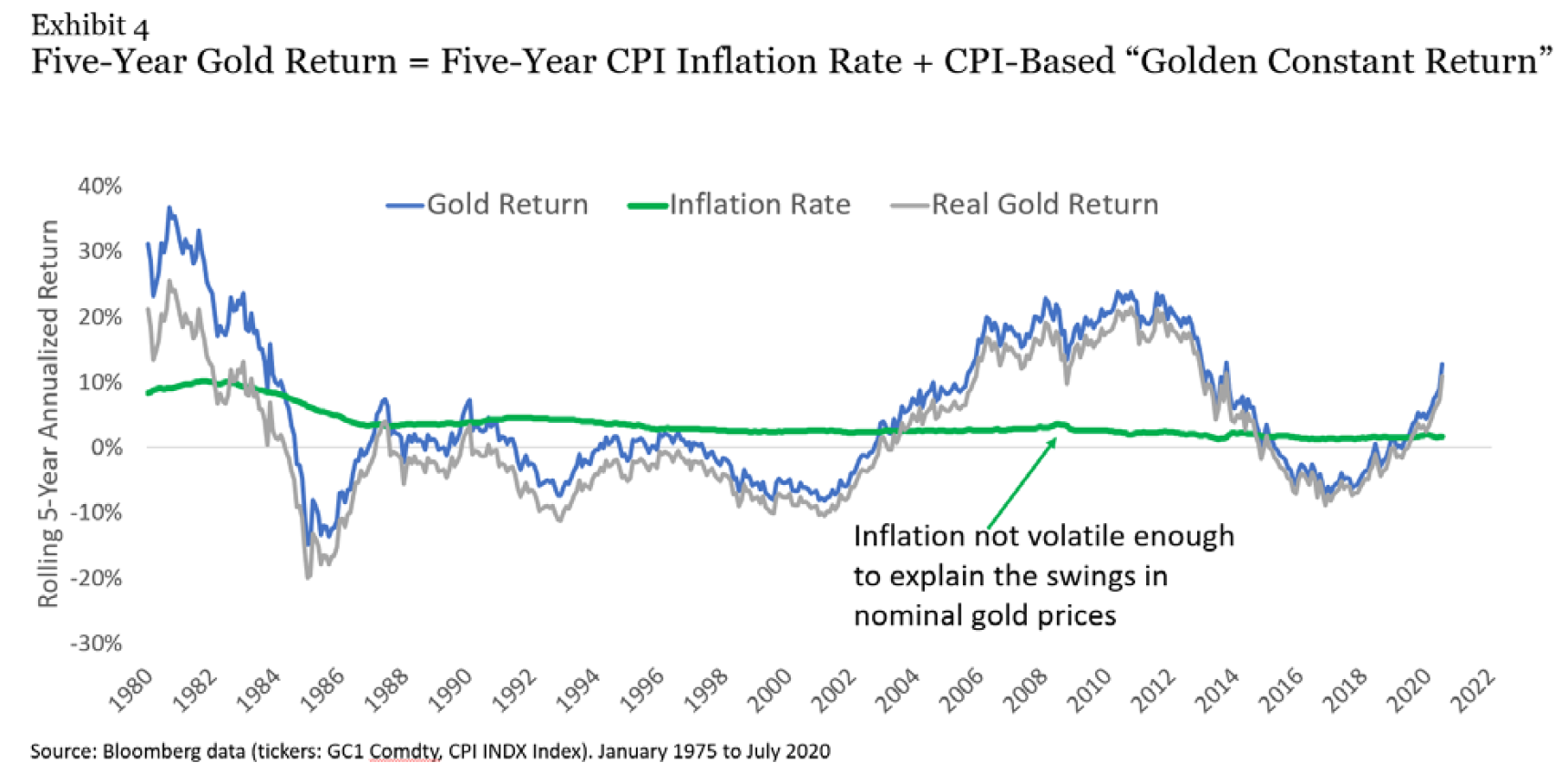

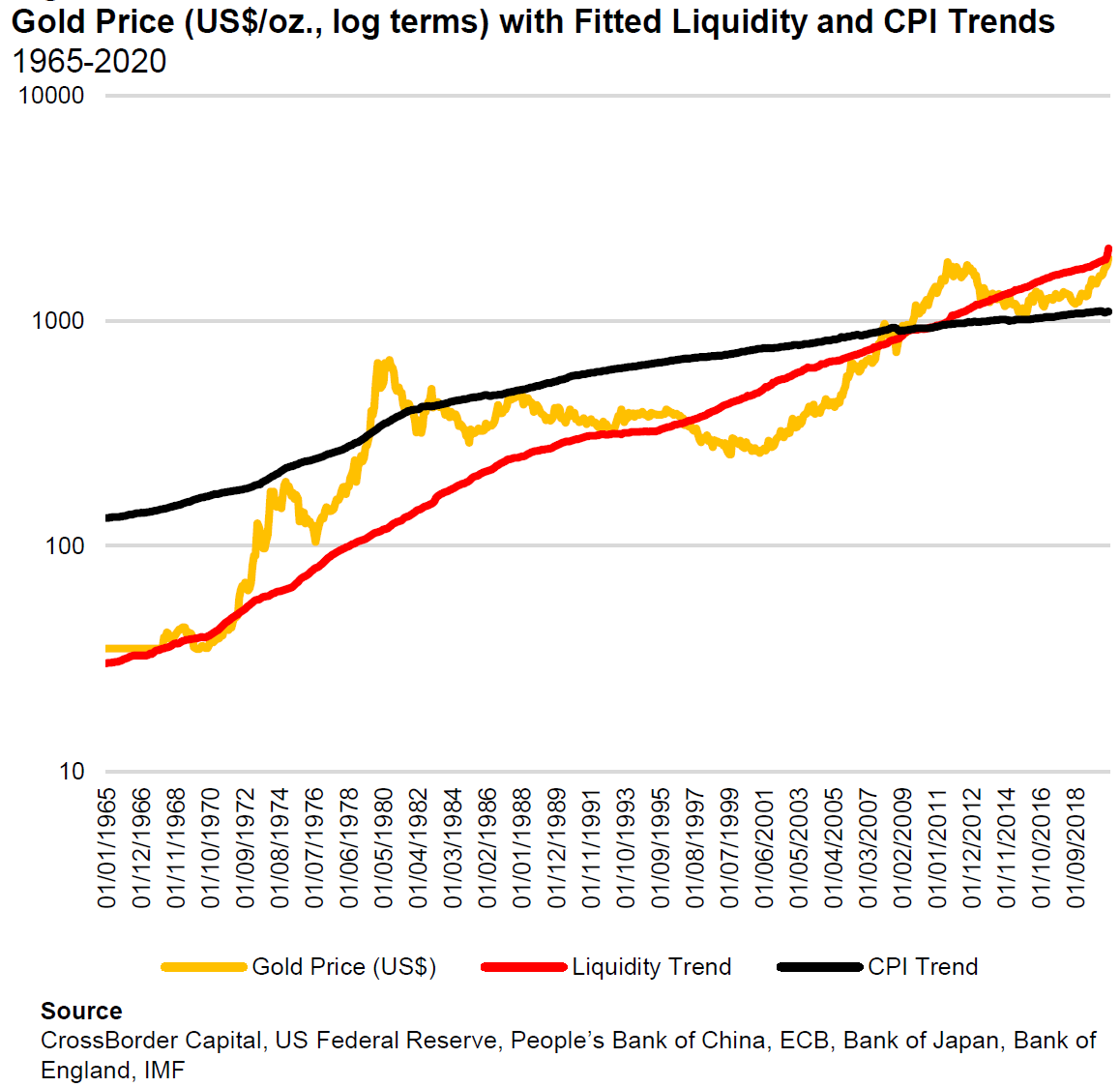

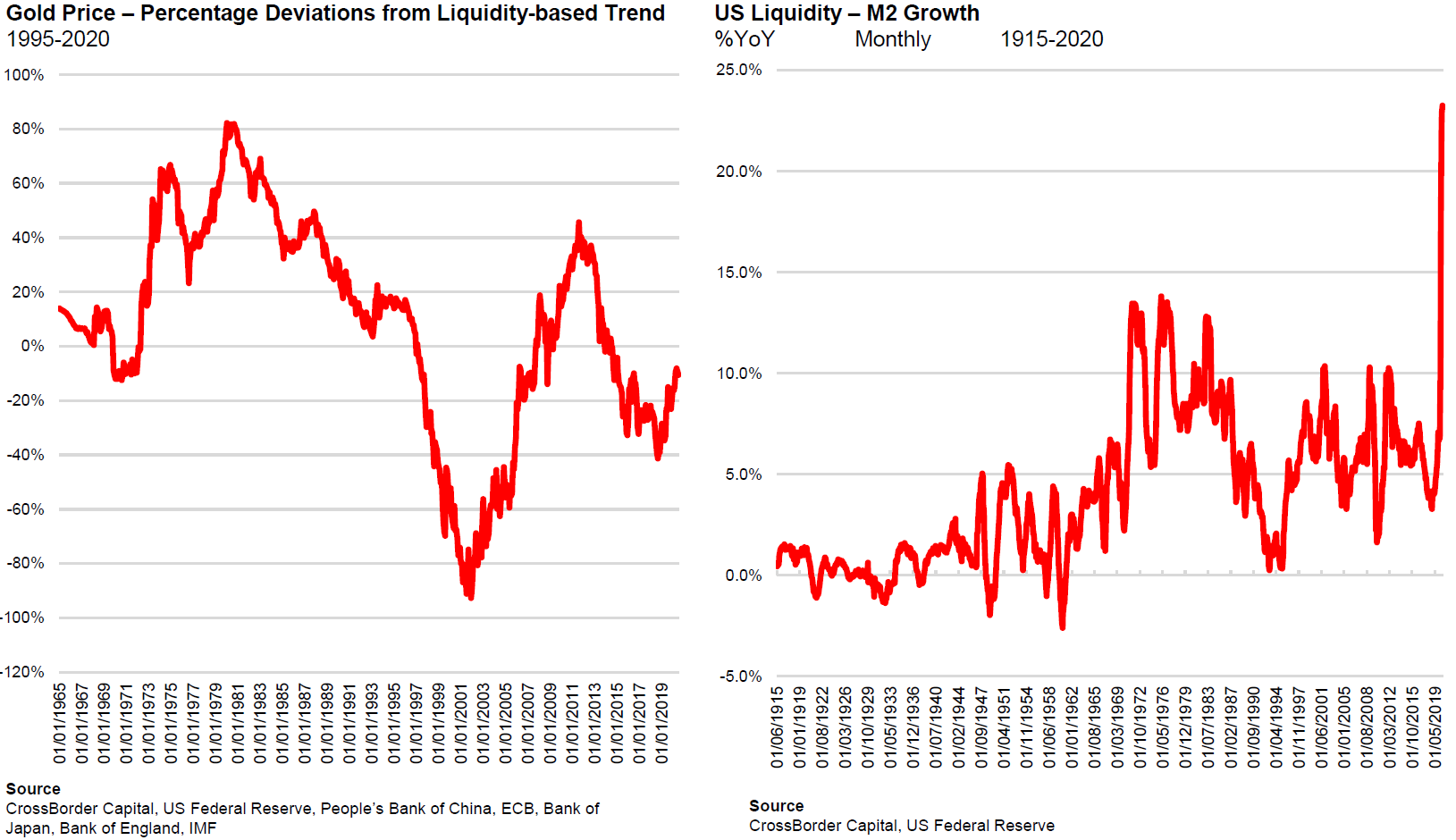

This process leads to the finding that gold is cheap. In the following chart, the blue line shows nominal gold, while the green line shows the price discounted by the level of the real yield for its empirical duration. This exercise shows that the launch of exchange-traded funds holding gold appears to have jolted the price upward, and that the metal also grew more attractive in the wake of the global financial crisis, when many braced for disaster. It has since given up those gains, but not those it made in the wake of the launch of ETFs. If investors grow as scared about monetary debasement as they did a decade ago, a development that is easy to imagine, then gold could rise further. In real yield-adjusted terms it is now at the bottom of its recent range. Why shouldn't it return to the top if sentiment sours?  However, two interesting new pieces of research suggest that the Pimco approach (which is in line with the method I've taken as gold has risen in recent months), has things the wrong way around. Most interesting is a paper by Claude Erb, Campbell Harvey and Tadas Viskanta called Gold, the Golden Constant, COVID-19, 'Massive Passives' and Deja Vu.Their research shows clearly that the correlation between the gold price and real yields isn't imaginary. But correlation still leaves open the possibilities of coincidence or (more plausibly in this case), that the line of causation moves in the opposite direction:  They suggest a framework based around the "real price of gold." This price is a notional accounting identity. If we know the price and earnings of a stock, then we also know its price-earnings ratio. Similarly, they argue, if we know the level of gold and of the consumer price index, then dividing the first by the second gives us the real price. When gold was $1,800.50 in June, and the price index was 257.2, the real gold price was 7. In January 1975, it stood at only 3.36, so in real terms gold is much more expensive than it used to be. Using this methodology, this is how the the real gold price has moved over time:  Thus, Erb and his colleagues have shown that the real gold price is almost as high as at its two previous peaks, in 1980 and after the crisis. Unlike the Pimco methodology, then, this approach finds that gold is already very expensive. What it has in common is that it finds the launch of gold ETFs, making speculation in gold far easier, was a moment when something important changed. This chart shows the correlation of the real gold price, as they define it, with the holdings of the two biggest gold ETFs. The correlation is significantly tighter even than the link with real yields:  If lots more people decide to try their luck with gold ETFs, this chart implies, the real price could go much higher. This would be an example of speculative excess, similar to what happened in 1980, and driven more by fear of disaster than by greed. Meanwhile, this approach suggests that shifting inflation levels and expectations don't matter anything like as much. If we look at inflation, nominal gold prices, and the real gold price by the Erb group's definition over time, we see that inflation is almost inconsequential compared to swings in the real price:  Returning to the analogy with stocks, this is akin to a finding that long-term returns are driven by fluctuations in multiples (and therefore animal spirits), rather than by earnings. What of the obvious correlation with real yields? Michael Howell of CrossBorder Capital Ltd. in London suggests that causation runs the opposite way. As he puts it: "Moves in the gold price drive real yields." He instead suggests that gold is a phenomenon of financial liquidity. When more money is available, the price will be higher, and vice versa. Rather than price gold in terms of fiat or paper money, he says, we should view paper money as being priced in terms of gold. The more money is in circulation, the higher will be the price of gold in terms of paper money. Here is the gold price since 1965, compared to inflation over the same period, and Howell's measure of liquidity, which combines figures from the Federal Reserve, the People's Bank of China, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England and the International Monetary Fund. It appears far more closely linked to liquidity:  That said, it doesn't follow liquidity particularly closely. As the research of Erb, Harvey and Viskanta suggests, there is a big element of pure speculation and animal spirits. But at present, gold is deviating below the trend in liquidity, which — as measured by the broad M2 indicator — just shot through the roof.  Howell suggests four factors can be shown to drive speculative interest in gold. First, each 1 percentage point rise in the future trend of inflation over the next year tends to increase the gold price by about 2% — so an increase in expected inflation from 2% to 3%, which would currently seem like an epochal shift, would be good only for a move of about $50 in gold. Second, unsurprisingly, deteriorating risk appetite over the preceding two years leads to higher gold prices. The massive loss of confidence during the Covid crash naturally led to greater demand for gold. Third, there is the Fed's balance sheet, and fourth there is "flight capital" from emerging markets, China in particular. His conclusion is as follows: What these factors tell us is that at times when US investor sentiment is structurally depressed; when global financial conditions are deteriorating sufficiently fast to stimulate a hunt for 'safe' havens, and when the Fed is trying to boost financial markets (and possibly also weaken the US dollar) with more liquidity, the gold price trades above its liquidity-based trend. This is happening right now, since all three boxes can be ticked. In addition, if and when inflation accelerates, expect a further overshoot in gold.

This adds up, naturally, to a very bullish prognosis. Howell thinks gold should reach $2,500 by the end of next year buoyed by liquidity alone, and could get to $3,000 if the various cyclical factors help it to overshoot. To bet against gold at this point is to bet that central banks reverse course swiftly and start mopping up liquidity and even raising interest rates — a realistic possibility only if the pandemic comes swiftly under control, and unambiguous inflation pressures recur. Absent a swift victory over the virus, all of these three varied methodologies suggest that there is far more room for gold to rise than to fall. Survival TipsI have two survival tips today. First, after the experience of the last few hours: Watching political conventions can be bad for your mental health, particularly if you are trying to write a complicated piece about gold at the same time. Second, a tip that will be too late for many of you: Try to avoid being a parent of a school-age child as schools wrestle with how to reopen. My children's schools held Zoom conferences this evening to explain how they are going to do this, and it is mightily complicated. Children will be divided into three cohorts, and go in every third day – which means that they will go to school twice some weeks, and once on other weeks, and that the days of the week when they are in attendance will vary. When they arrive, they will have as many desks and tables as usual, but two-thirds of the chairs will be missing. Even though they are maintaining their distance, they must wear masks at all times. Some rules veer toward the surreal or macabre. Two of my kids go to one of the few New York public schools that has a uniform. That uniform is to be worn when they are on premises. When they are on Zoom, uniforms aren't needed, but the school felt it necessary to stress that clothing is compulsory. Neither pajamas nor nudity will be tolerated. Safety regulations are painful. In the event of a fire drill, social distancing rules will continue to apply. If it is an unplanned fire alarm, however, social distancing rules will be suspended. They will also be suspended in the case of an active shooter. Children will be allowed to hide together in the same closet, which was good to know. I shouldn't make this sound like pointless red tape. The schools have had to change their curricula so that the same class can work just as well for the 10 kids physically present and the 20 following online. It's been a massive logistical and pedagogical challenge just to come up with a plan. I am well aware that I and my kids are among the lucky ones. The great majority of parents are in a much worse position. School reopening matters greatly, and so a critical moment is coming in the world's attempt to recover from the pandemic. The New York Times's stalwartly liberal columnist Michelle Goldberg, and my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Joe Nocera have both written recently about how important and painful the school reopening will be, and how it has been made unnecessarily difficult. Any operation this complicated has a high chance of going wrong -- and a failed reopening would have a severe effect on confidence, public health and (less importantly) markets. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment