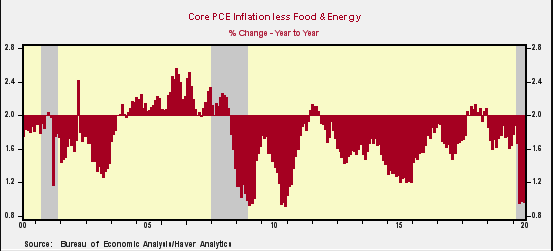

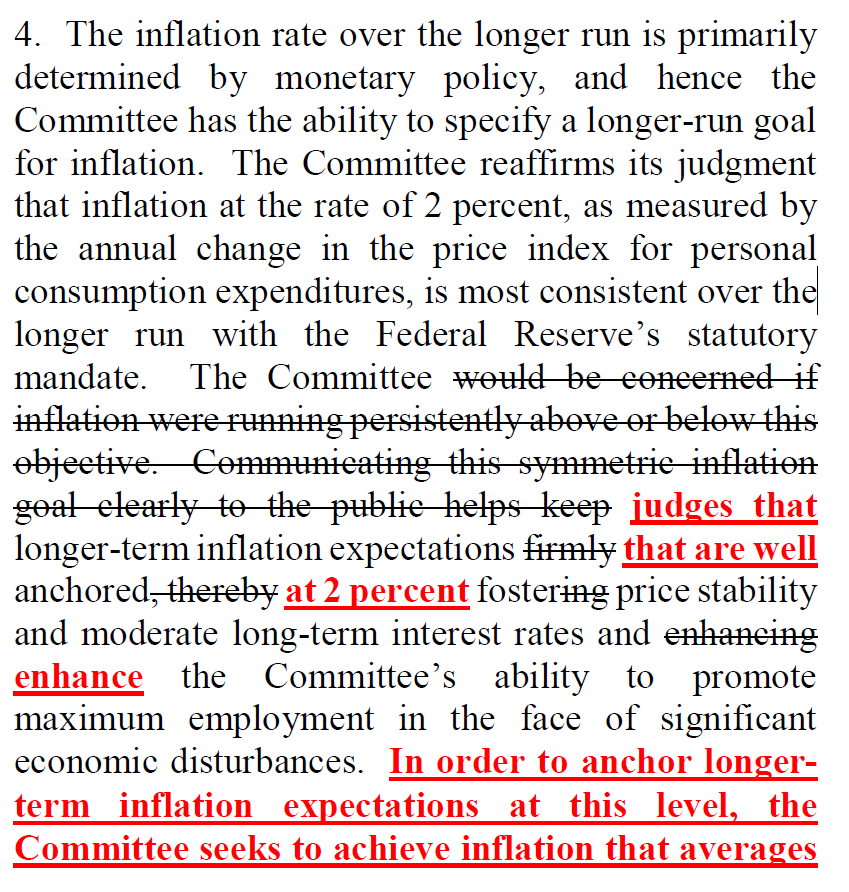

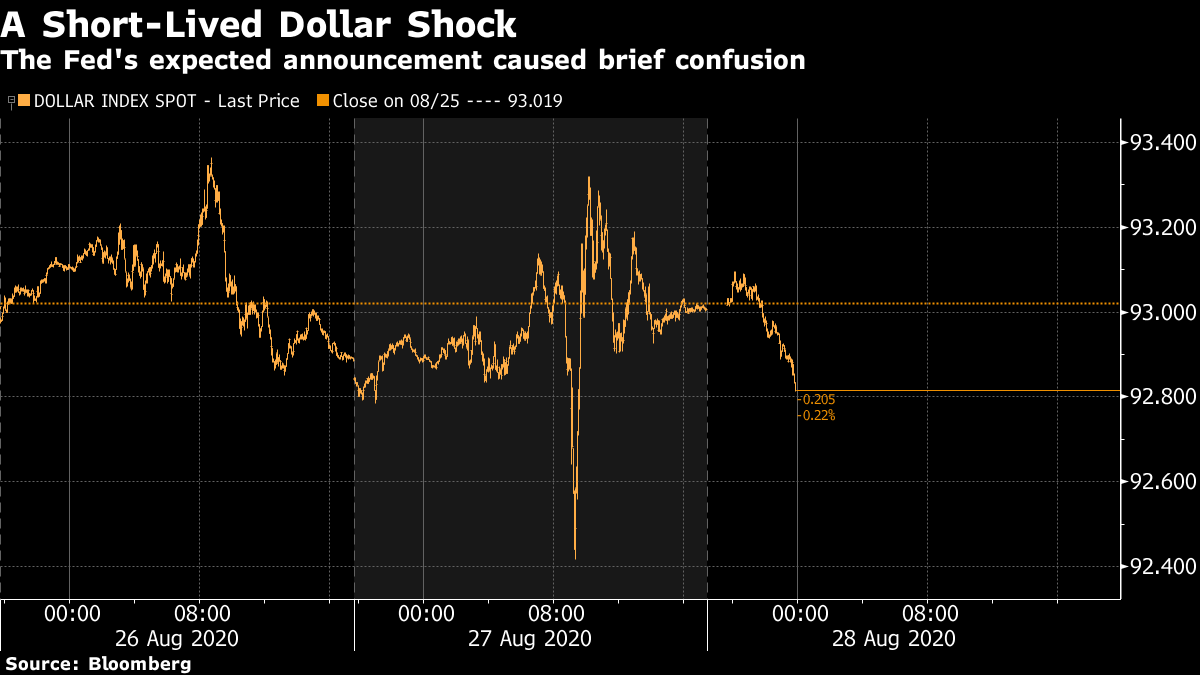

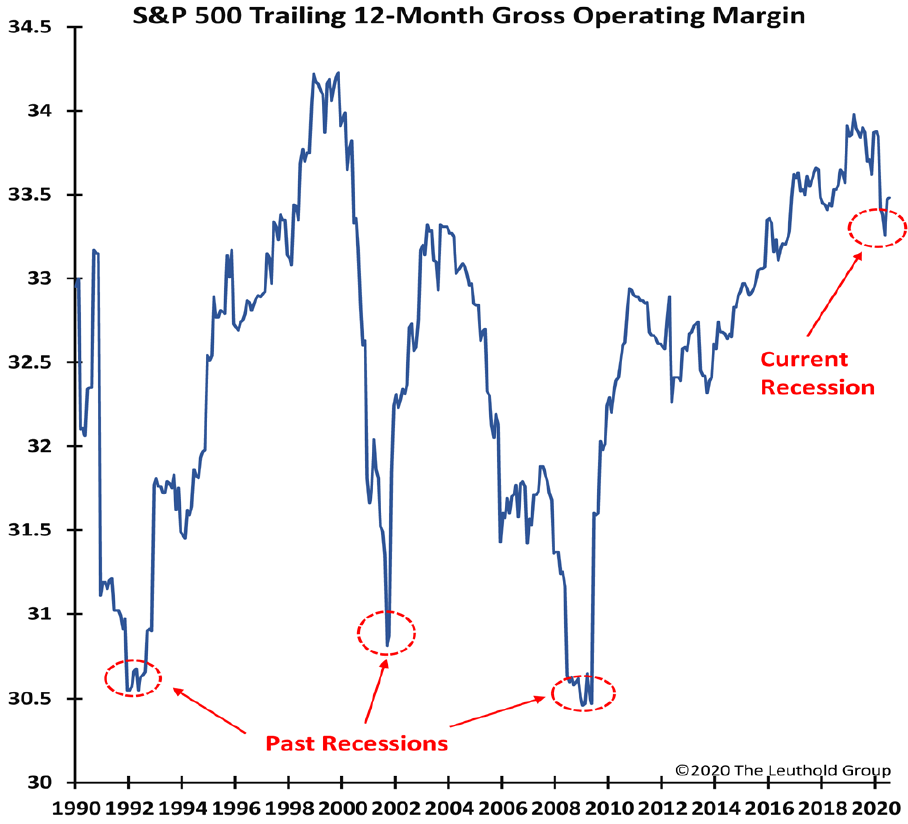

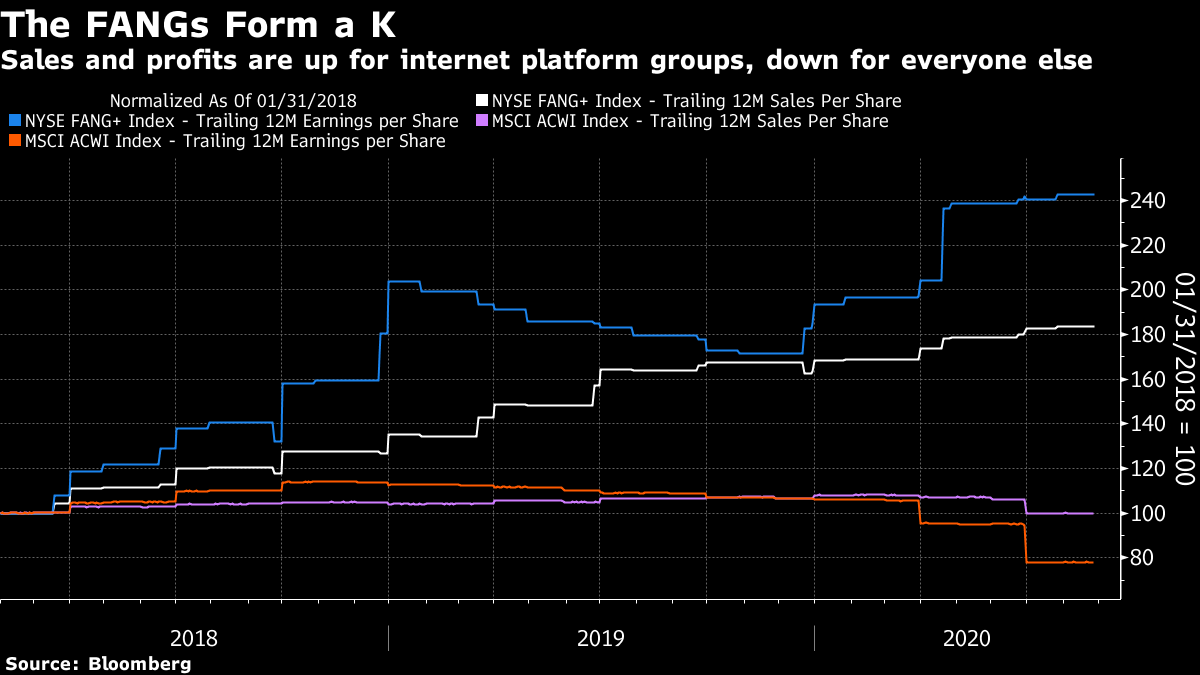

The Reliant Robin Inflation Target Jerome Powell has unveiled a new long-run strategy for the Federal Reserve, the world's largest central bank. His announcement, which will lead to targeting an average rate of inflation over time and is hence more permissive than the current strategy, was largely expected but is still a very big deal. It made me think of Reliant Robins. The Reliant Robin is an extremely cheap three-wheeled car that used to be popular in the U.K., even though it became the butt of many jokes. Those curious can watch a clip of television presenter Jeremy Clarkson test-driving a Robin here. One of the jokes against owners was that they were only too happy to get a speeding ticket, because that would prove it could go that fast. By the same token, the Fed's announcement that it will let inflation go a bit above 2% if necessary sounds like wishful thinking. Would that the economy were strong enough to generate price growth that fast. As this chart from Berenberg Capital Markets' Mickey Levy makes clear, the Fed's announcement that it might let the economy "run hot" and allow inflation to hit 3% or more looks about as relevant as a 100mph speed limit would be for Reliant Robin drivers.  The Fed comes in a for a lot of criticism, much of it deserved, so it's worth stressing that its "Fed Listens" exercise has been transparent. The report is available, as is the analytical work that went into this strategy change, along with summaries of the various conferences held. The basic shift in philosophy is easily traced by looking at how the wording in its central strategy document has changed. This is the key passage, handily annotated by the team at NatWest Markets. Words in red and underlined have been added:   This is all reasonable, as far as it goes. At this point, it would be silly for the Fed to leap in and try to squelch any nascent rise in inflation just to keep it at 2%. As the Fed has said, a "persistent undershoot of inflation from our 2% longer-run objective is a cause for concern," as it could lead to Japanification, a deflationary cycle in which spending is forever deferred. There are many reasons for the persistent undershoot. The critical one is that changes in the labor market, which is now dominated by relatively low-paying and non-unionized jobs in services, mean that rises in employment are less likely to lead to strong gains in wages. In these circumstances, pressing to eliminate inflation at the first sign of strength in the job market is politically unfeasible. Inflation targeting covers one side of the Fed's dual mandate to maintain a stable currency and full employment. There is another important, less well-rehearsed development. Ranko Berich, head of market analysis at Monex Europe Ltd., made the following point: "The change in the statement is subtle, merely saying the Fed will consider "shortfalls" from maximum employment as opposed to "deviations". However, in his speech Powell explained the significance of the change. Whereas previously, the Fed would be willing to hike interest rates as the labour market approached estimates of maximum employment, Powell has made it clear that uncertainty around these estimates mean that they will not be relied upon as much in the future. Instead, Powell stated "employment can run at or above real-time estimates of its maximum level without causing concern, unless accompanied by signs of unwanted increases in inflation". This is a clear break with prevailing policy wisdom going back as far as the 1980s - its significance is difficult to overstate. The sub-text of these changes is that the current leadership has concluded the Fed raised rates too quickly after the last crisis, and is determined not to make that mistake again. The problem, as put neatly by my colleague Brian Chappatta, is that while the Fed has demonstrated immense power to move markets and asset prices over the last decade, it has no shown no similar power over the economy. Its conventional tools are no longer enough to push inflation permanently above 2% (just as pressing on the accelerator of a Reliant Robin won't make it move at 100mph). There was no detail on how exactly the Fed will get inflation above 2% and keep it there. That will be a question for specific monetary policy tactics rather than strategy, presumably. As often with a Fed chairman, Powell is wise to give himself flexibility. There is still ample reason for criticism and doubt. Plainly the Fed will be more dovish than before, all else equal. Berenberg's Levy was caustic but fair: The critical issue the Fed has not answered is: why has the Fed's monetary ease since the financial crisis failed to stimulate economic activity sufficiently to lift inflation to 2%? Over the years, the Fed's arguments that the Phillips Curve has become flatter has been an ex post rationale for the persistence of low inflation consistent with low unemployment. But it reflects the Fed's lack of understanding of the actual inflation process. In reality, inflation has remained sub-2% because the Fed's policies have failed to stimulate a persistent increase in nominal GDP above productive capacity, so that, with little excess demand, there is only modest inflation. So the issue remains: will the Fed's ultra-easy policies actually stimulate accelerating economic activity, or just pump up asset prices and make the stock market happy? The answer to Levy's question will unfold over months and years to come. As the decision wasn't a great surprise, the market reaction doesn't tell us much. Bond yields rose quite significantly, while inflation breakevens continued to increase while staying well below levels that would test the Fed's commitment to letting the economy run hot. The dollar was all over the place before ending, at midnight in New York, almost exactly where it was 24 hours earlier.  In the short term, this means more of the same for financial markets — stronger stocks, and a weaker dollar. Non-U.S. assets, including emerging markets, should benefit. A continued flat yield curve and low rates will probably prolong current trends within the stock market, with financial shares being clobbered, and growth beating value. In the immediate future, the fight against the pandemic, and the U.S. election, will matter more. In the longer term, it's hard to avoid the feeling that this is a pivotal moment, possibly one that ends four decades of orthodoxy since Paul Volcker took over the Fed and showed he was prepared to raise rates even if it crushed employment. That policy worked, but the economy has now moved on to a point where the Fed needs to promise not to raise rates, even if inflation takes off again. Let's all hope that the results are as beneficial to the economy as the Volcker medicine proved to be in the 1980s and 1990s. Pandemic Profitability The economic shock suffered by the world earlier this year was the biggest seen in generations. The same isn't true of corporate earnings, at least if we look at big U.S. companies. The following chart is from Leuthold Group's Jim Paulsen, and shows that trailing 12-month earnings per share are down 15% from their peak. Assuming forecasters are right that earnings recover from here, that means that there have been nine earnings recessions at least as bad as this one since the war. Most have been far worse:  Usually, corporate earnings (shown in blue in the following chart from Paulsen) are a kind of geared play on the economy. A fall in GDP will be accompanied by a worse fall in profits. This recession is a huge outlier:  We cannot account for all of this with greater profit margins for companies, either. This next chart compares the S&P 500's annual sales growth with nominal GDP growth. Usually, sales are a geared play on the economy, like profits. This time, once more, it is the other way around:  Why? As this is the political convention season, I will offer a choice of narratives. They aren't mutually exclusive. Paulsen points out that this was an unusual recession in that households entered it having already de-levered. With the onset of the crisis came payment protection for those who lost jobs, and renewed rock-bottom rates. Thus the blow to families was expertly cushioned, and with debt service costs so low, it was unsurprising that sales continued to be healthy.  Another argument, which might go well with politicians of a more left-wing persuasion, is that profit margins normally fall sharply during a recession, and this time they haven't. There are various potential explanations, but a boom in monopolistic behavior, fostered by permissive competition policies (which have persisted under both parties for decades) would certainly be a plausible one. Despite the economic horrors of this year, companies cannot be too worried about the competition if they continue to get fat margins:  The S&P isn't a direct reflection of the U.S. economy, of course, because its companies derive so much of their revenue and profit beyond American shores. As the pandemic has been a global phenomenon, this shouldn't have that great an effect. But to add grist to the notion that the world has a problem with monopolies, I offer the following chart, tracing growth in earnings and sales per share for the NYSE Fang+ index, and for the MSCI ACWI index, which covers both developed and emerging markets, since the beginning of 2018. These charts form a beautiful "K." The Fangs' earnings have increased by about 140% in that time, while the ACWI's earnings are down 20%. The Fangs have done this on sales that have increased about 80% (in 30 months!), while sales for world stocks as a whole are flat:  While the world's economy went pear-shaped, corporate earnings appear to have been K-shaped. Survival Tips I was planning to write something about the increasingly weird battle to take over TikTok, but didn't have time. Instead, I will share two videos on the general "tick-tock" theme. They illustrate that two Irishmen who both get an oddly bad press in middle age were very exciting in their youth. Try "Like Clockwork" by the Boomtown Rats, fronted by Bob Geldof, performed at the Hammersmith Odeon in 1978. It starts with a great chorus of "tick tock tick tock." I once had the privilege of interviewing Geldof in the unlikely surroundings of a CFA Institute conference, and found him as decent and charming as anyone I've spoken to as a journalist. He now invests directly in Africa through private equity. I discovered afterward that many people dislike him and it's hard to understand why. Live Aid was, after all, rather wonderful. Live Aid brings me to 11 O'Clock Tick Tock as performed at Red Rocks near Denver in 1983 by U2, who would shoot to great fame at Live Aid two years later. U2 in general and Bono in particular get a bad rap these days. This is a little easier to explain. They're still going, they're very rich, they haven't produced anything good in years, and Bono has also made an unlikely transition to private equity. But none of this matters. I was 18 when I first saw them live, in a concert that started with "11 O'Clock Tick Tock," and I'm incapable of hearing this song without feeling the same excitement. With a birthday coming up this weekend, at an age when birthdays are no longer welcome, I could do with that. Watch it. It's really, really good. Have a good weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

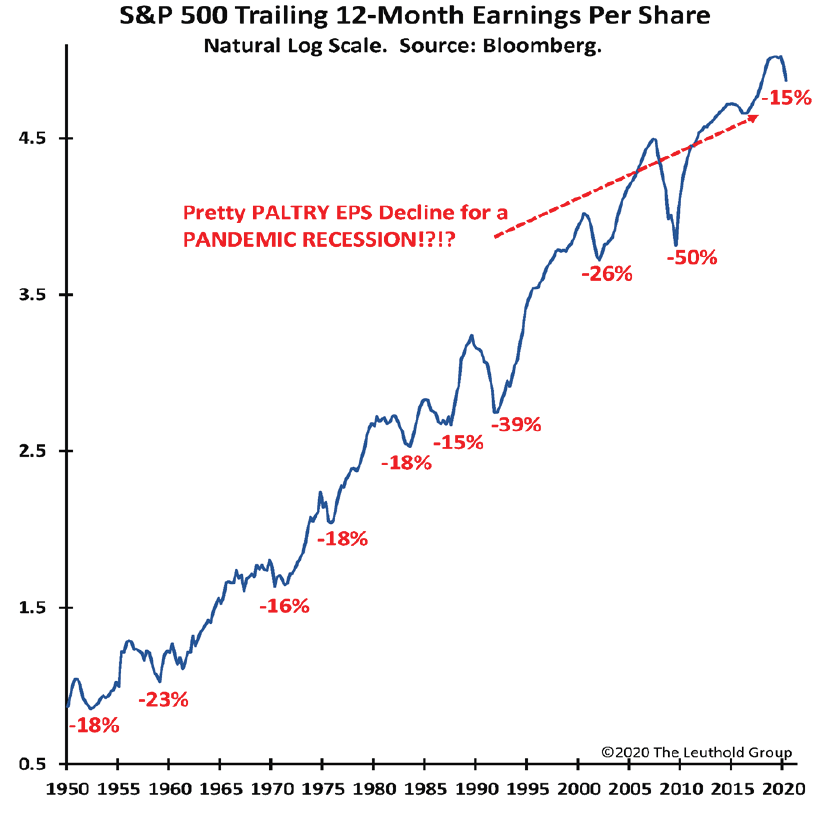

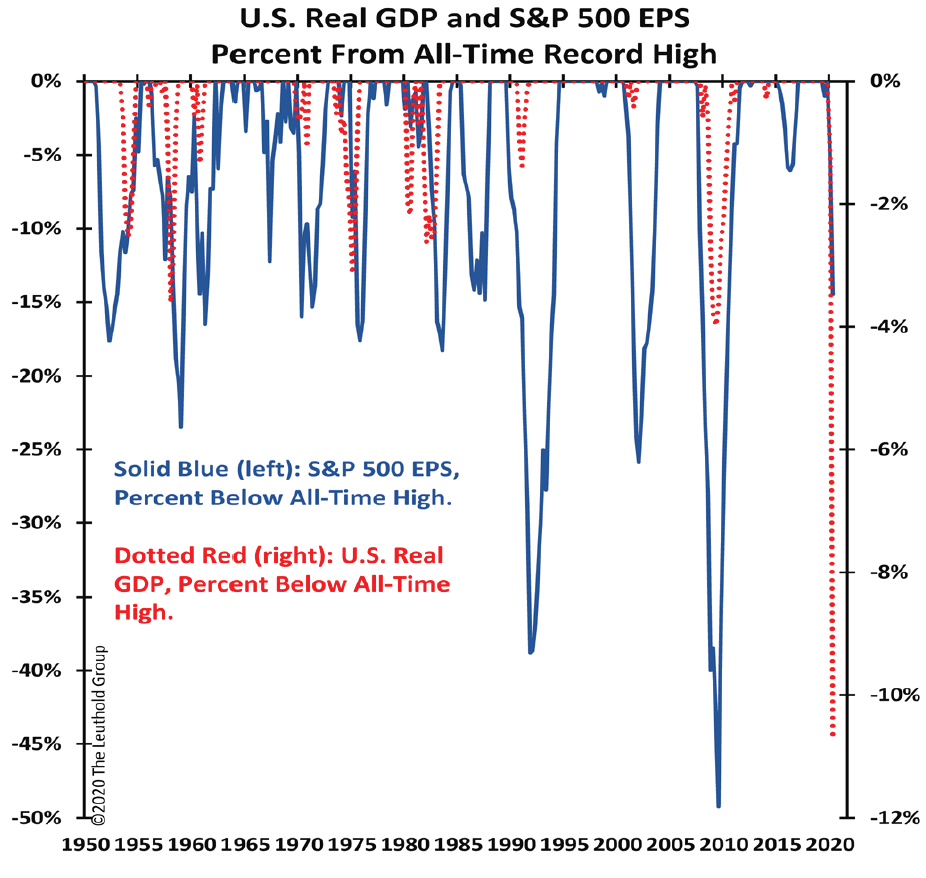

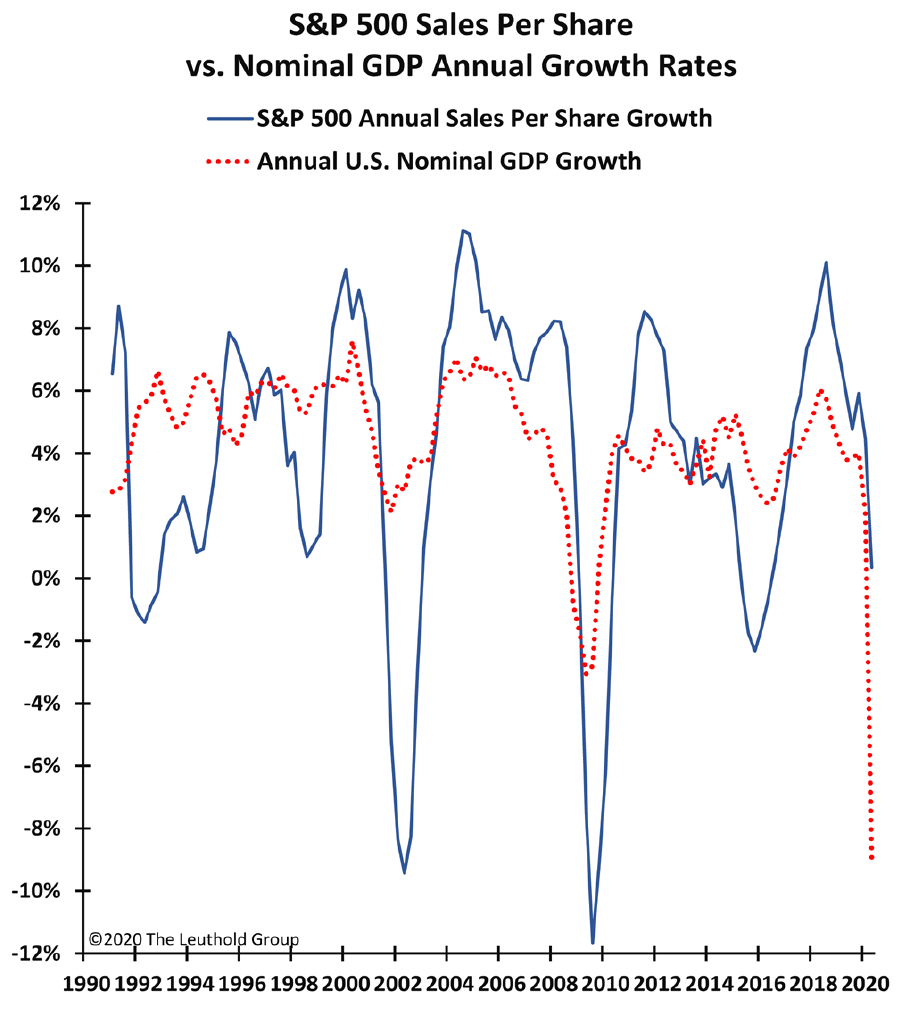

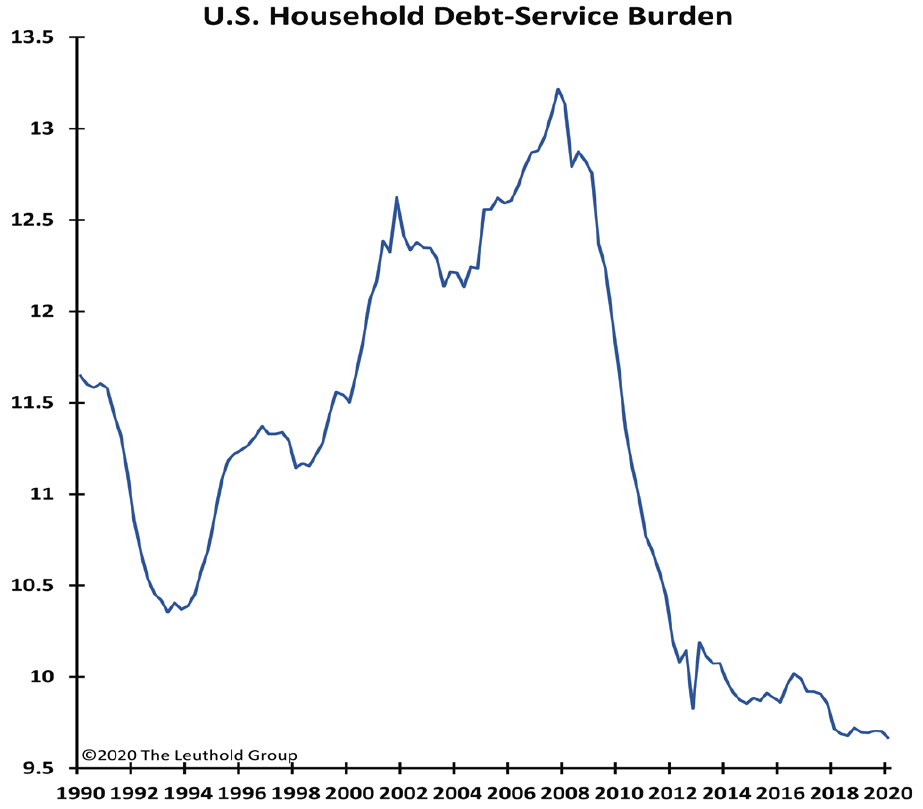

Post a Comment