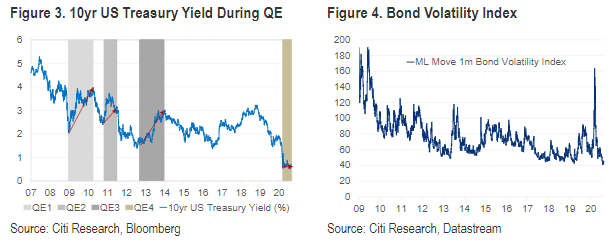

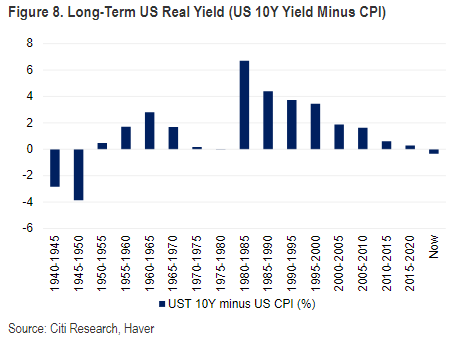

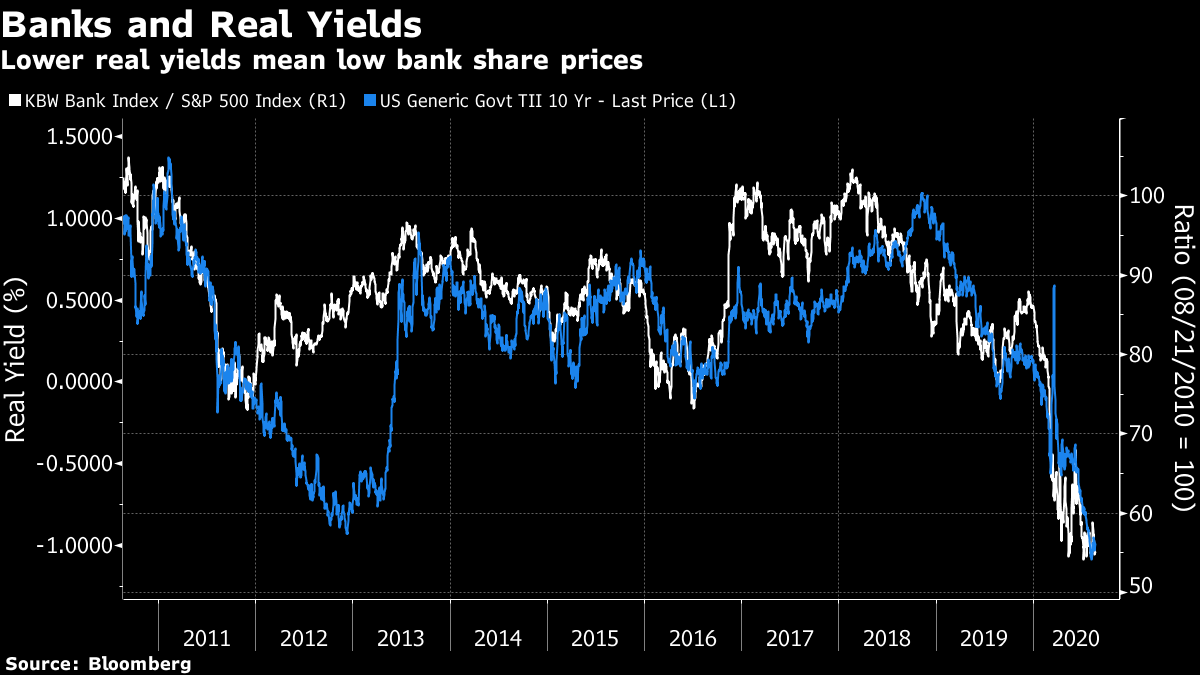

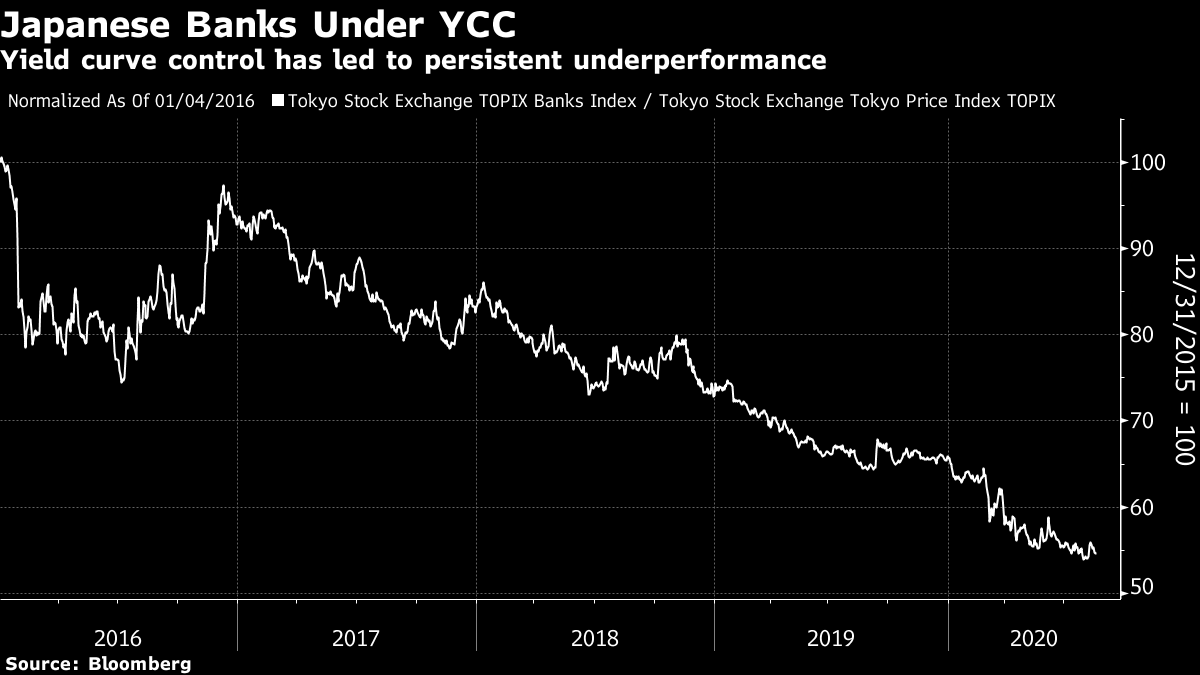

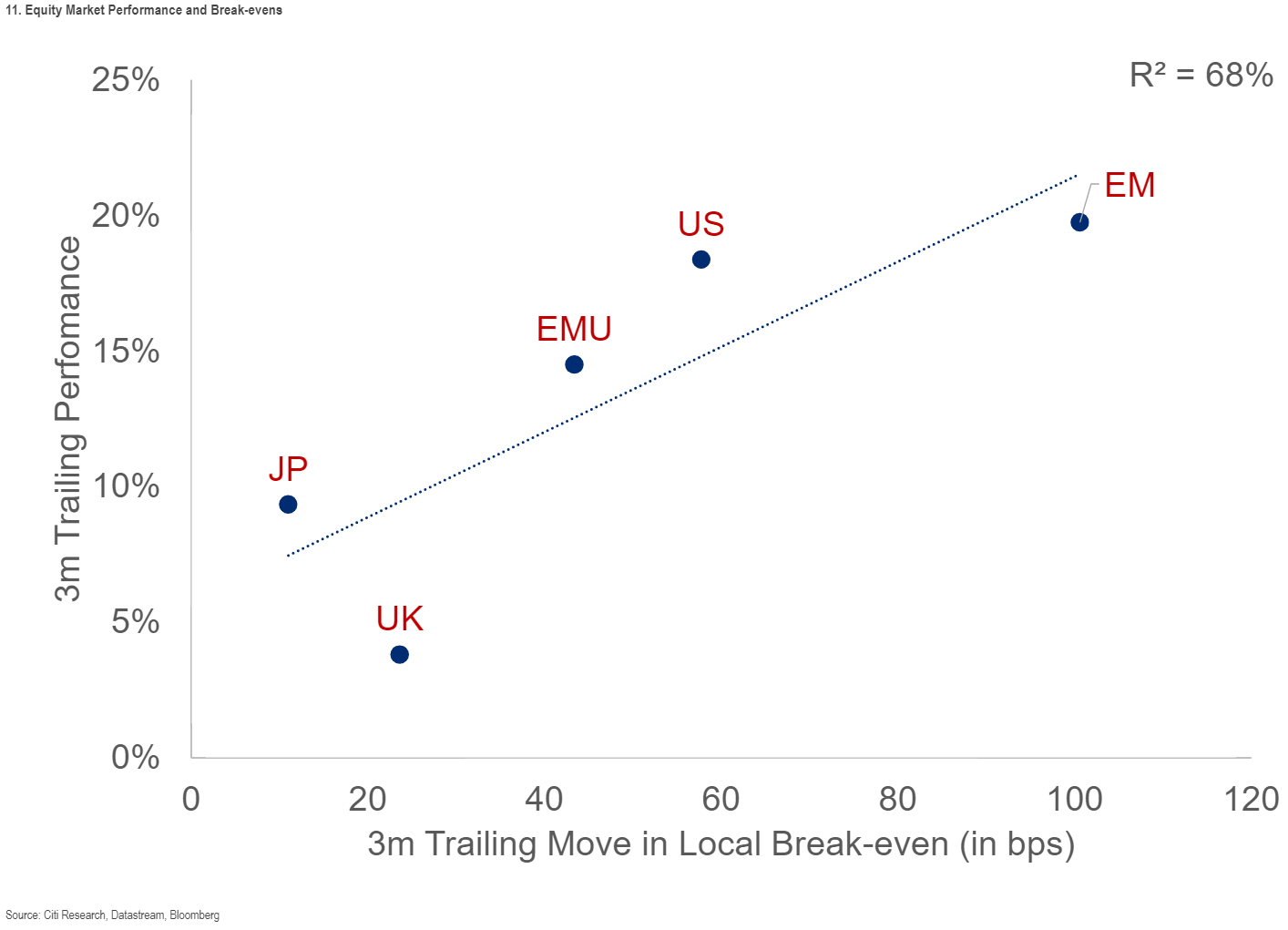

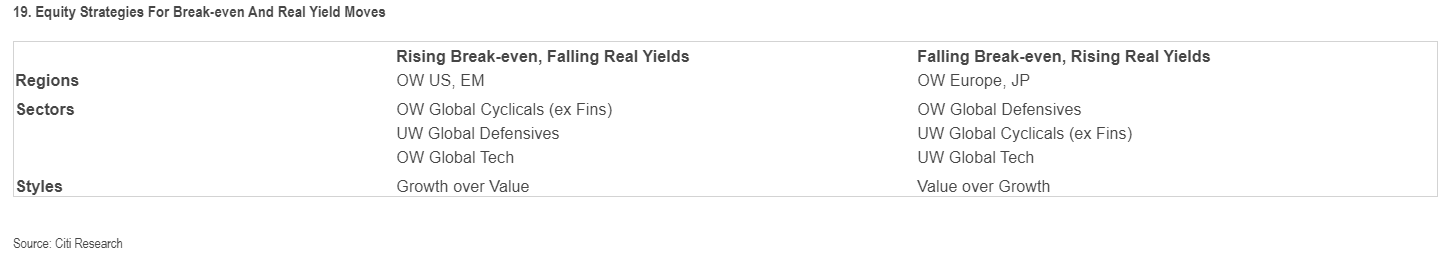

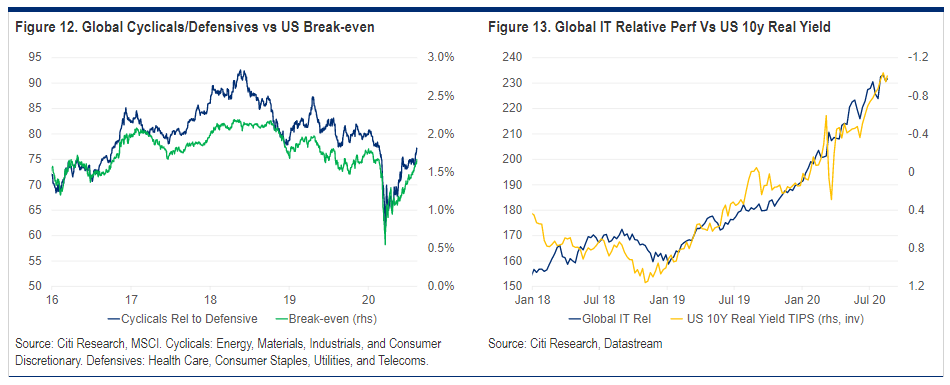

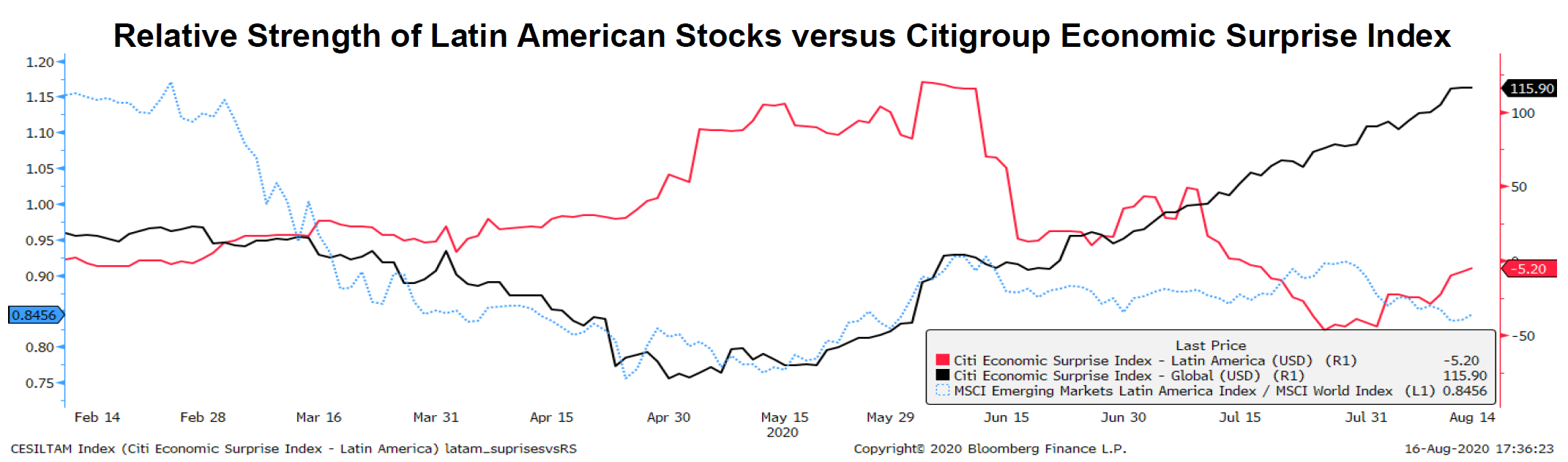

Minutes to Midnight The world hasn't changed that much. What the Federal Reserve says still matters, a lot. For evidence, look at the market reaction on a quiet Wednesday in August when the minutes to the latest Federal Open Market Committee meeting were published. We had already heard the chairman's gloss on the discussion that the committee had, and there are ideal moments to unveil a new policy direction straight ahead, in next week's annual gathering of central bankers in Jackson Hole, Wyoming (which, unfortunately for the bankers, will be virtual this year, denying them the chance for some fresh air in the great outdoors), and in next month's FOMC meeting. But even so, there was one sentence in the minutes that turned the markets around. The words that mattered were:"many participants judged that yield caps and targets were not warranted in the current environment but should remain an option." This commits the Fed to nothing at all. A year ago, it might indeed have been remarkable to hear that caps on bond yields, a very direct interference in the operation of the free markets, should "remain an option." And the Fed is also leaving plenty of other radical options open: "many participants" also commented that "it might become appropriate to frame communications regarding the Committee's ongoing asset purchases more in terms of their role in fostering accommodative financial conditions and supporting economic recovery." That implies that the Fed is no longer thinking of its asset purchases as a rescue mission for an illiquid market, but as a weapon for stimulating the economy — and that in turn implies that big asset purchases will be with us for a long time. That kind of thing is generally good for asset prices. But what reverberated with the markets was the language about yield curve control. If "many" participants don't think it's needed, that is a strong hint that it isn't happening. And a separate sentence told us: "Of those participants who discussed this option, most judged that yield caps and targets would likely provide only modest benefits in the current environment." Not only is yield curve control not warranted, many of them think, but it wouldn't help much if it was attempted. The result was a sudden and sharp correction for 10-year real yields:  q Meanwhile stocks gave up gains, setting a tone that continues in Asia at the time of writing, while gold also endured a sharp sell-off. The Fed might not think that YCC is a big deal, and think there are better ideas for pumping up markets and the economy, but the instinctive market reaction suggests that investors disagree. They think yield curve control is a big deal, and dislike the hint that it isn't going to happen in the U.S. That they feel this way tells us something about the market. As the following chart from Citigroup Inc.'s global investment strategist Rob Buckland shows, the latest dose of QE has been received differently from those that preceded it. The QE campaigns that followed the last financial crisis saw plenty of bond market volatility, and also saw yields rise as the asset purchases went on. This time around, the Fed hasn't so much calmed the market as anesthetized it:  As I've commented before, markets are behaving as though yield curve control is already in place. As a result, nominal yields have stayed put while inflation breakevens have risen sharply. This is very unusual, and is redolent of the post-war policy now known as "financial repression" when yields were deliberately capped to help the government pay off debts incurred to fight the war. As this chart from Buckland shows, real yields (defined as the nominal yield minus current inflation rather than predicted inflation) have just gone negative for the first time since the 1950s:  If markets disliked those comments about yield curve control so much, it suggests that a lot of money is now resting on the Fed coming through with another dose of financial repression, and allowing inflation to rise. Here are some consequences: Real yields and banks Nobody suffers from low real yields quite like banks. The relative performance of the the large U.S. banks has tanked this year, directly in line with the fall in real yields. Such low yields make it harder for banks to make a profit from lending. Over the last 10 years, as the chart shows, bank stocks' relative performance has tracked real yields almost perfectly. The one big exception came in 2012 when the Fed's promise of "QE Infinity" brought real yields to a new low, while bank stocks rallied. At that point, the (correct) belief was that QE wasn't in fact forever. This time, investors are behaving as though it is a permanent fact of life:  This is rational enough if you believe the Fed really is going to opt for yield curve control. The Bank of Japan became the first major central bank to adopt explicit yield curve targeting in early 2016. Japanese banks had been caught in the doldrums for a generation already at that point. But as the following chart shows, they have suffered fresh woes in the five years of YCC:  Meanwhile bank valuations have tumbled to levels barely higher than at the nadir of 2011 and 2012, when the banking industry had to deal with the debt ceiling imbroglio in the U.S. and the euro zone's sovereign debt crisis. At present, U.S. banks trade for less than book value, while euro-zone banks trade for less than half their book value:  That is mighty cheap. If they had been priced on the assumption of YCC for years into the future, maybe such cheapness is justified. If there is a way to craft a post-Covid recovery without such explicit interference in bond markets, banks might well be too cheap. International markets and inflation breakevens Meanwhile, if the Fed is serious about letting inflation rise well above 2%, and the minutes have plenty of language that suggest it is, that also has implications for international asset allocation. A few months ago, we went through possibly the greatest deflationary shock in history. Inflation expectations have been steadily rising around the world since then. And this following chart, from Buckland at Citi, shows that rising inflation breakevens have correlated nicely with stock market performance — probably because any belief in increasing inflation tends to imply a belief that an economy has enough life to generate some demand:  A world in which inflation is allowed to rise rapidly is a world in which emerging markets can perform nicely, along with the U.S. It is not so great for Europe or Japan, which are much more deeply immersed in deflationary dynamics. So far, this reflects little more than a bounce back from a deflationary shock. But what if it continues? Real yields, sectors, and breakevens Broadly, there are three possible paths. The first two assume that nominal yields stay pegged, and so either breakevens rise and real yields fall, or breakevens fall and real yields rise. This would flow through into some clear winners and losers, which Buckland handily summarizes as follows:  Falling real yields, so far, have been great for technology, the U.S, emerging markets, and cyclicals. They have been horrible for value, led by financials. If breakevens start to fall, that would be good news for defensive stocks, value, and Europe.  Meanwhile Vincent Deluard, macro strategist at StoneX Group Inc., bangs the drum for Latin America as the ultimate inflation hedge. The region was hit in the neck in the early weeks of the crisis, it has had disappointing economic data since then, and a number of South American countries have had particularly horrible Covid-19 outbreaks, led by Brazil. And yet, Deluard points out, it has actually outperformed the developed world over the last month, according to the MSCI indexes. If you want an inflation hedge, it may well be found in the unloved stock markets of Latin America:  There is a final option, that central banks don't lean on the bond markets, and yields do rise as inflation expectations move higher. That seems unlikely in the near term, but the extent of the market reaction to a couple of sentences in the Fed minutes suggest that it is being taken for granted nothing like this will happen. In the longer term, if inflation really does return, abetted by the logjams and bottlenecks that must inevitably have been caused by the pandemic, then a return to rising nominal yields grows that much more plausible. The market's response looks like an overreaction to me. The Fed seems very happy to move to a form of average inflation targeting, and to treat yet more huge asset purchases as a means to rebuild the economy, and that implies that we can safely assume a lot of easy money in the future, even if it comes in a technical form other than yield curve control. But if markets are that jumpy about this, it does imply that the risks of a genuine recovery, bringing with it an end to financial accommodation, are being underestimated. If Covid-19 comes under control much quicker than expected, either through herd immunity or through a successful vaccine, the Fed could leave the field quickly and nominal yields could rise in a hurry. If you think this is going to happen, maybe buy some banks. Survival Tips This newsletter has been delayed by my attempt to write it while also keeping an eye on the Democrats' presidential convention. Covid-19 has rendered it a truly weird occasion. The politicos don't get much time to expand on an argument, but I think the night established that Barack Obama still knows how to make a good speech. Indeed, he is almost as good as his wife. As for the choice of Kamala Harris as vice-presidential nominee, I think everyone can agree that this is great news, because it means that Maya Rudolph will be back to do her utterly brilliant Kamala impersonation on "Saturday Night Live." If you want to survive American election season, nothing beats SNL and in particular its skits on the debates. This one, featuring Jason Sudeikis as Joe Biden facing off against Tina Fey as Sarah Palin in 2008 (and Queen Latifah as the late Gwen Ifill) is well worth watching; and I think may favorite of all time is this one from 2000, with Will Ferrell as a clueless George W. Bush, up against an insufferably smug Al Gore, played by Darrell Hammond. Gore was forced to watch it by his advisers, to grasp how dreadfully he was coming across, and it may have changed history. I suspect the next two months of American politics will be very hard to survive; SNL, with Maya Rudolph as Kamala, is going to help. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment