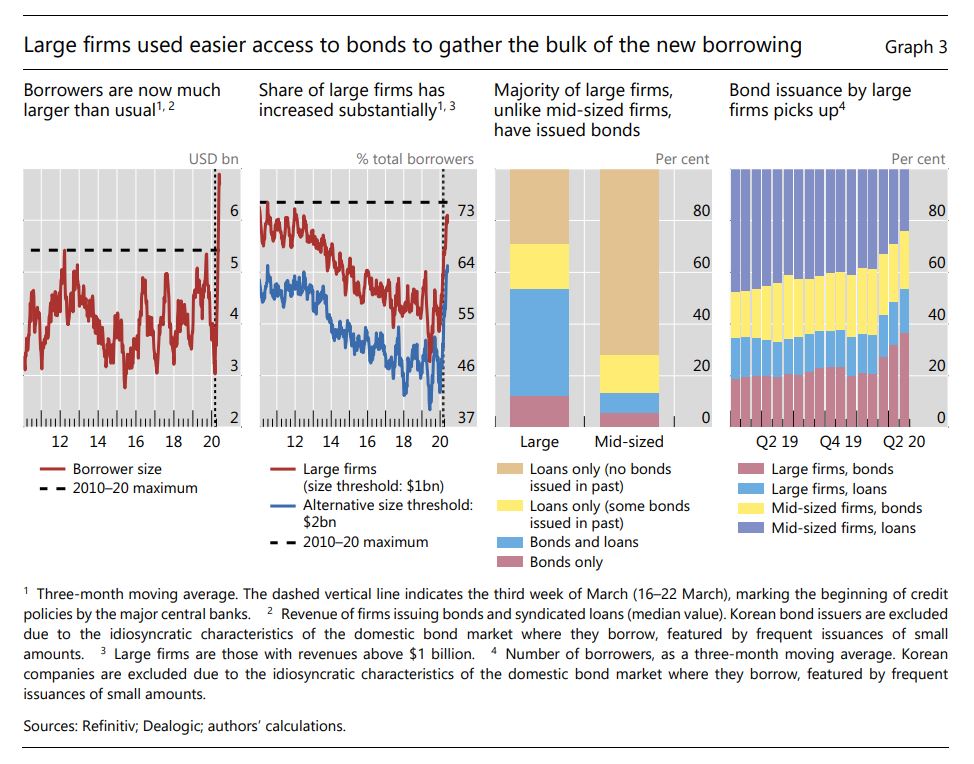

The U.S. deploys further measures to restrict Huawei's reach. Markets in Southeast Asia lag behind due to a lack of tech stocks. And the Bank of Japan isn't making it easy for traders to work from home. Here are some of the things people in markets are talking about today. The U.S. Commerce Department announced further restrictions on Huawei Technologies aimed at cutting the Chinese company's access to commercially available chips. The move builds on restrictions announced in May, and is just the latest news in an increasingly tense relationship between the world's two biggest economies. The changes add 38 Huawei affiliates in 21 countries to an economic blacklist as the U.S. seeks to limit adoption of the company's 5G technology. The restrictions are likely to further hit both Huawei's 5G base stations and its smartphone businesses because it relies heavily on foreign chips to make those, further denting China's ambition to play a key role in global rollout of 5G technology. Huawei's stockpiles of certain self-designed chips essential to telecom equipment will run out by early 2021. Asia stocks looked set to climb Tuesday after a rally in technology shares boosted their U.S. peers. Treasuries rose and the dollar retreated. Futures pointed to modest gains in Australia, Hong Kong and Japan. For the third time in a week, the S&P 500 Index rose above its February closing record during the session, but ended below it. Fresh Chinese stimulus buoyed the benchmark, but lingering tensions continue to weigh on sentiment as the U.S. announced new restrictions on Huawei. The Nasdaq 100 outperformed, while big banks sank after Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway pared stakes in many of the industry's top names. Oil jumped to a five-month high on optimism about an economic recovery, while gold pushed higher. As markets around the world piggyback on technology shares to ride a startling rebound from their pandemic lows, stock investors in Southeast Asia are proving to be mere spectators. Laden with so-called old-economy stocks such as those in the finance and real-estate sectors, the MSCI Asean Index is down 19% in 2020 even as similar gauges for Asia Pacific and world equities have wiped out their year-to-date losses. The poor show has also put Asean shares on course for their worst annual performance relative to global peers since 2013, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. "As long as tech rally lasts, Southeast Asia will continue to underperform due to a lack of those companies," said Nirgunan Tiruchelvam, head of consumer equity research at Tellimer. Technology stocks have been at the forefront of the worldwide equity rally from March lows as the virus outbreak accelerated the global shift toward automation. The new normal of remote work has yet to reach the traders who deal with the Bank of Japan, which doesn't allow home computers to connect to its network for conducting asset purchases and other market transactions. As coronavirus cases in Tokyo surge, that's raising concerns at financial firms. At least three have asked the BOJ whether traders can participate in its operations from outside the office, only to be met with a refusal, people familiar with the matter said. The so-called BOJ-Net infrastructure, used for trillions of yen in transactions daily, is connected via dedicated cables to computers at dozens of financial firms so they can trade assets with the central bank or buy bonds from the government. The monetary authority is concerned that allowing access from home would risk cybersecurity, the people said, asking not to be named because the matter is private. By contrast, the U.S. Federal Reserve and European Central Bank have allowed trading with counterparties at home. Google and Australia's competition watchdog exchanged online fire after the U.S. company warned that an imminent law governing revenue-sharing with the media will force it to disclose sensitive data and jeopardize free services like YouTube.The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission fired back, saying the envisioned legislation won't require Google to charge unless it chose to, prompting the U.S. company to accuse the agency of misrepresenting its views. Australia's government in July ordered Facebook and Google to share revenue generated from news articles. Both will have to negotiate with traditional media on remuneration in good faith. If no agreement is reached, there will be a binding arbitration process, and penalties for breaching the code can reach A$10 million ($7 million) or 10% of local revenue. The move aims to correct what the government says is a power imbalance between two of the world's most profitable companies and a local media industry that's bleeding jobs as it loses advertising revenue to digital platforms.What We've Been ReadingThis is what's caught our eye over the past 24 hours: And finally, here's what Tracy's interested in this morningSales of investment-grade corporate bonds in the U.S. have surged to $1.346 trillion so far this year, already surpassing a previous record set back in 2017. So who's issuing all that debt? And what for exactly? As my Bloomberg colleagues report, companies have rushed to issue in a bond market supported by the Federal Reserve. They're refinancing debt due in months and even years, taking advantage of the opportunity to extend their maturities at ultra-low costs as yields and spreads converge thanks to an almighty rally in in interest rates.  BIS: Large firms used easier access to bonds to gather the bulk of the new borrowing Bloomberg But a new Bank for International Settlements bulletin picks up the theme of inequality in today's capital markets. Researchers there point to a discrepancy between bond markets that are wide open for the biggest issuers and loan markets that have seen a tightening of available credit. Since smaller firms tend to be active in loans rather than bonds, the dynamic has contributed to an imbalance in the availability of capital. Put another way, booming bond markets mean the big are getting bigger. The share of large firms tapping the bond market has jumped to more than 70% of all borrowers, and the average size of borrowers in terms of revenue is twice that at the beginning of the crisis, according to the BIS. The irony of course is that the biggest companies with the greatest access to capital are getting it in spades, locking in lower funding costs and building up massive cash buffers that could theoretically give them an advantage for years to come. It's a weird consequence when the Federal Reserve professes to be worried about the impact of monopsony on the overall economy. You can follow Tracy Alloway on Twitter at @tracyalloway. |

Post a Comment