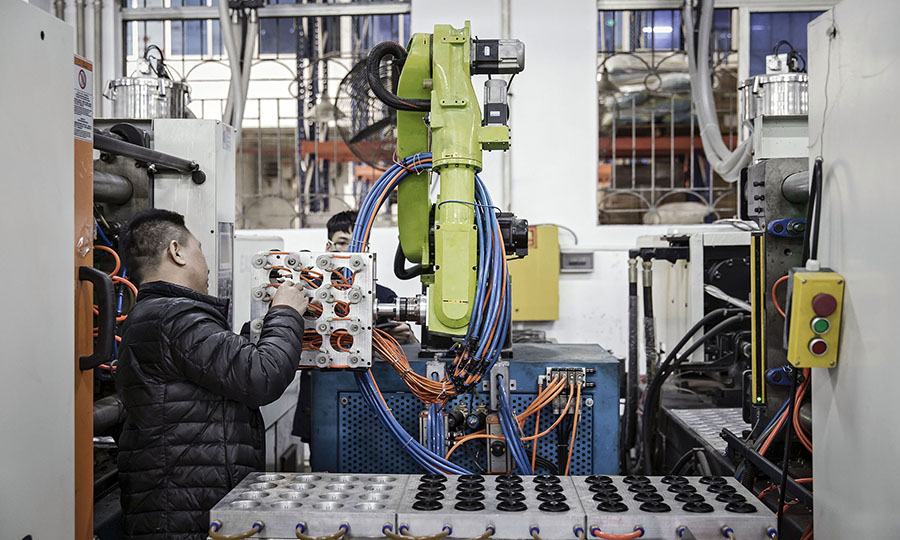

| Pampering the affluent is big business. Whether they're in the office or on the road, the well-off demand to be fed and lodged, kept secure in clean surroundings, groomed, entertained and otherwise fussed over. That's why Covid-19 lockdowns have had such a devastating impact on workers in the industrialized world. In the U.S., one in four workers provide these kinds of personal services. Many of those jobs will never come back. Even if vaccines and therapies manage to tame the pandemic, it seems likely that the wealthier classes will work from home more, and travel less.  This week in the New Economy The broader trend of digitization, which enables remote working and discourages business travel, will create a tsunami of economic consequences everywhere. Since the worldwide lockdowns began, there's been astonishingly rapid growth in digital services covering everything from health care to home deliveries. A decade of expected advances in these areas has been compressed into two or three months. Combined, these powerful trends are delivering a shock to the global workforce of historic proportions. In the European Middle Ages, the Black Death killed so many serfs that it drove up the price of labor and collapsed the value of land, which lay untended, hastening the end of the feudal overlords in England. Covid-19 will have precisely the opposite effect. Many economists predict that this pandemic will lead to a surplus of unskilled labor, thus lowering its cost, while concentrating wealth in the hands of the modern lords of the manor—the tech titans who control the world's digital commons. India's richest tycoon, Mukesh Ambani, added $22 billion to his fortune this year as his conglomerate, Reliance Industries, shifted its focus to e-commerce. Apple, meanwhile, became the first U.S. company to achieve a $2 trillion valuation even as unemployment in the U.S. rose to its highest level since the Great Depression.  A technician adjusts an industrial robot on the production line of Guangdong Shiyi Furniture in Foshan, China. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg Over the long run, digitization is likely to boost productivity and benefit societies overall. The problem is the here and now. Overnight, cameras are replacing security guards; drones are taking over from delivery drivers; and crawling robots are doing away with floor cleaners and window-washers. The venture capital investor Kai-Fu Lee hails a "great robotic leap forward" underway in China as businesses increase safety—and lower costs—by removing "human touch-points" from their operations. As goes China, so goes the rest of the world, he declares, confidently forecasting new jobs will be created for building and maintaining digital infrastructure like 5G networks, repairing robots and manually collecting data needed as "fuel" for artificial intelligence. Left unanswered, however, is the question of how unskilled workers can be retrained for these tasks: In China, writes former Bloomberg Businessweek reporter Dexter Roberts, less than one-quarter of rural youth, the main pool of unskilled labor, has completed high school. Workers all around the world need a new deal. Even before Covid-19 struck, it was clear that America's social contract was in tatters. Inequality was growing as companies grabbed an ever-larger share of national income at the expense of rank-and-file workers. And although the job market was buoyant, the longer-term prospects for workers were sinking: most of the new jobs were lower-quality with fewer hours and low wages. Pampering, it turns out, is a precarious occupation. There is no shortage of prescriptions for how to move forward. Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist David Autor suggests a number of solutions: Making permanent the extension of unemployment insurance to independent contractors and others who previously didn't qualify; investing to upskill those whose jobs were made redundant; building public infrastructure.  Andrew Yang Photographer: Adam Glanzman/Bloomberg In political circles, the idea of a Universal Basic Income is making a comeback. Andrew Yang mounted a U.S. presidential campaign this year on a promise to deliver a monthly $1,000 "Freedom Dividend" to all U.S. citizens over the age of 18. In a research paper, former Obama administration economic adviser Lawrence H. Summers, now a professor at Harvard University, and Anna Stansbury, a PhD. candidate there, argue that the fundamental problem is that workers lack the power to claim more corporate profits, leaving the lion's share to owners of capital. "Overall, we believe that increasing worker power must be a central and urgent priority for policymakers concerned with inequality, low pay and poor work conditions," they write. The Bloomberg New Economy has made a new deal for workers a central theme of this year's forum, coming up in November. It's an urgent task: the global economy faces its steepest contraction since 1870, according to the World Bank. Recovery will depend in large part on how well societies care for workers who make their living by looking after those much more fortunate than themselves.

__________________________________________________________ Like Turning Points? Subscribe to Bloomberg All Access and get much, much more. You'll receive our unmatched global news coverage and two in-depth daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. Maps reveal and shape the space around us. Sign up for MapLab , Bloomberg CityLab's biweekly newsletter that decodes maps' hidden messages. Download the Bloomberg app: It's available for iOS and Android. Before it's here, it's on the Bloomberg Terminal. Find out more about how the Terminal delivers information and analysis that financial professionals can't find anywhere else. Learn more. |

Post a Comment