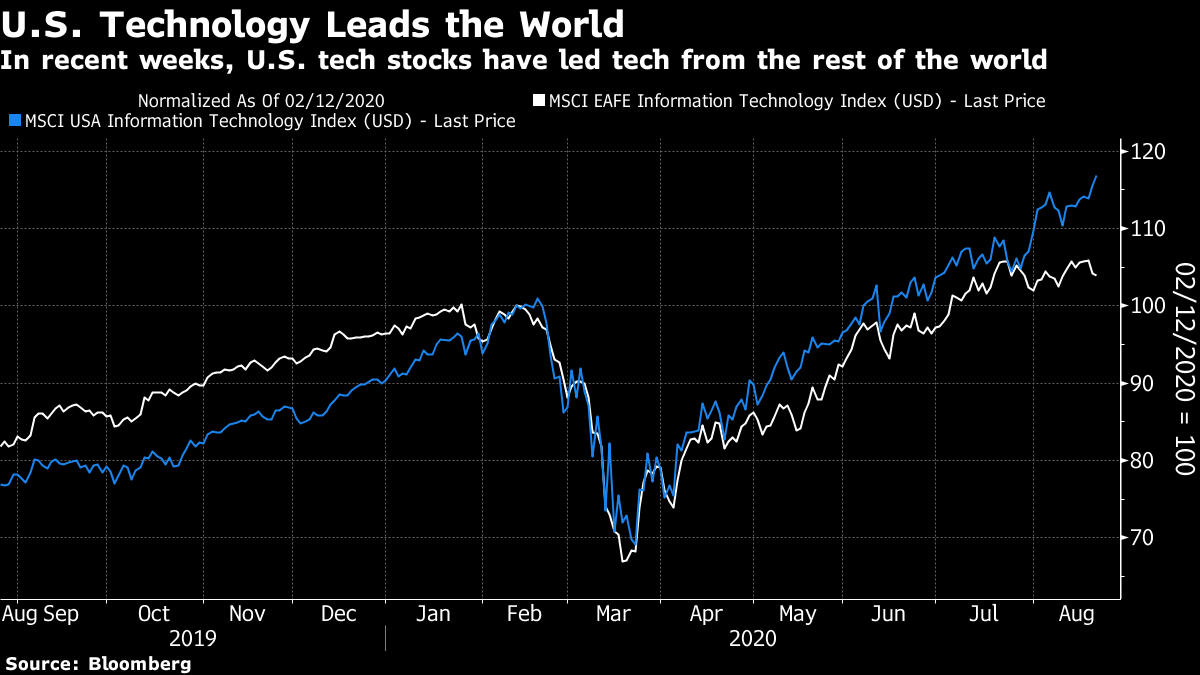

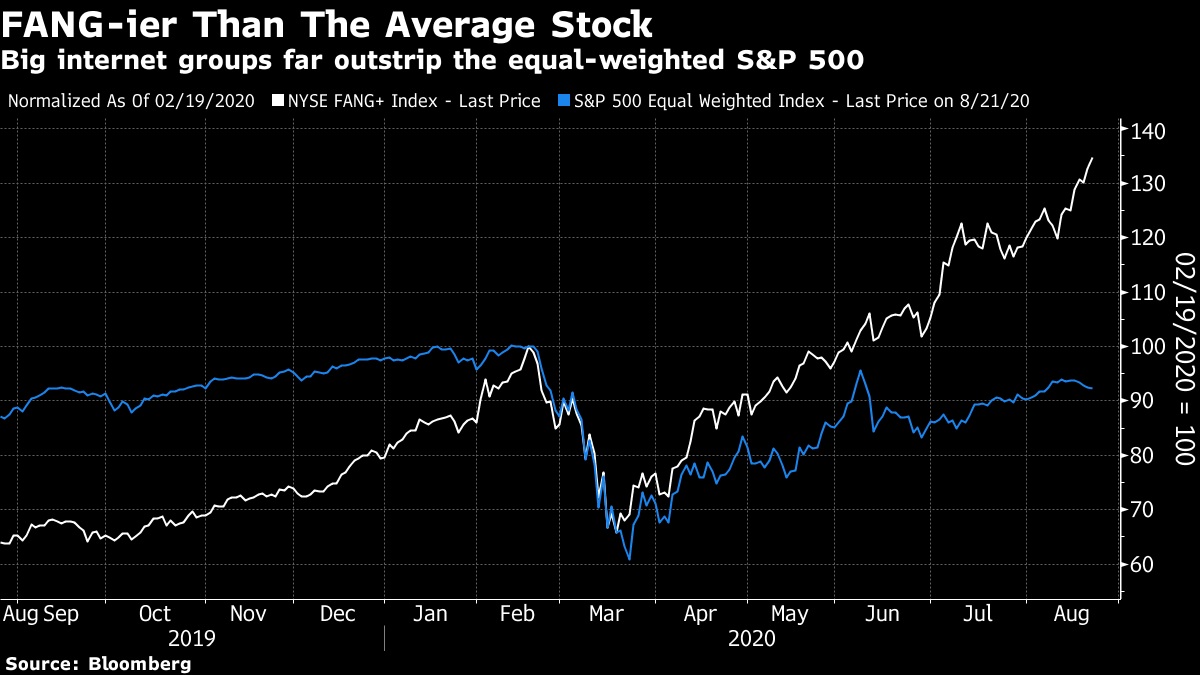

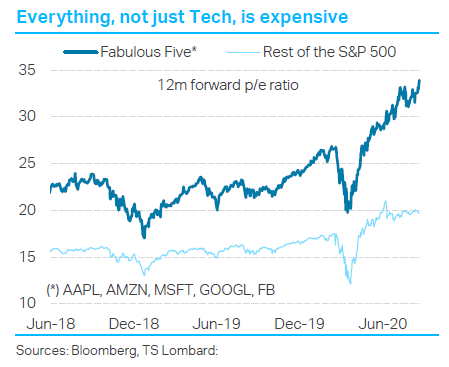

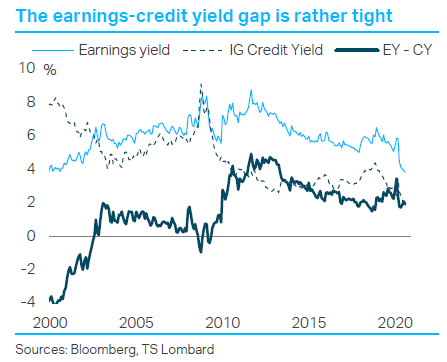

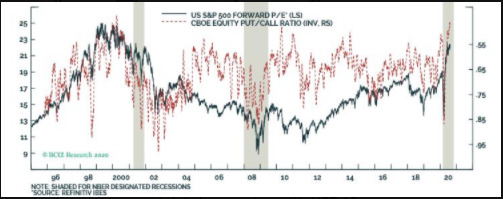

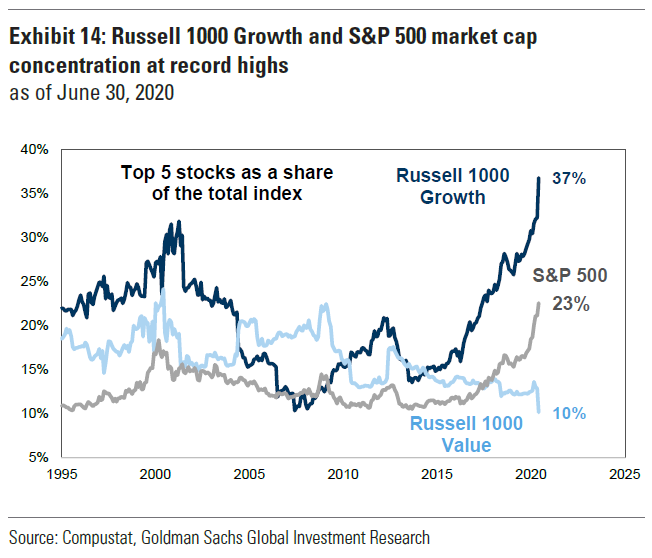

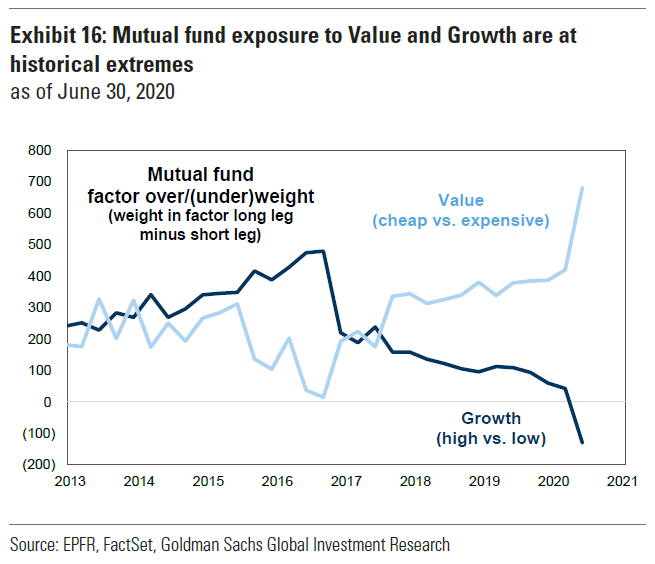

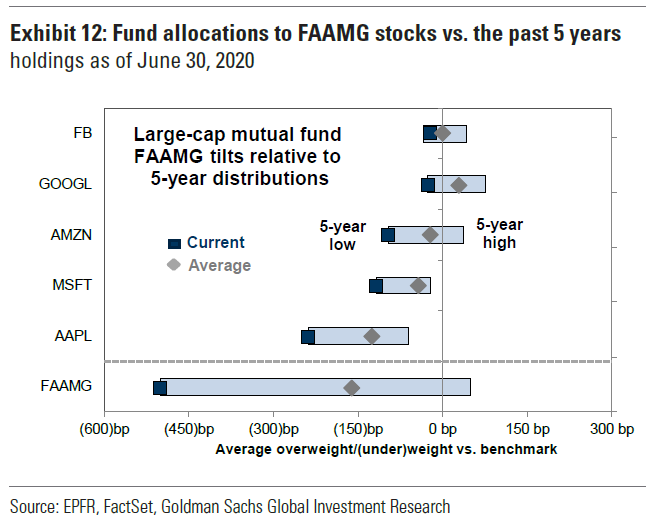

There's Always a SequelWay back in 1999, cable audiences could thrill to Pirates of Silicon Valley, a made-for-TV movie of the battle between Steve Jobs's Apple Inc. and Bill Gates's Microsoft Corp. It ends with Jobs back at Apple and having to swallow his pride by announcing an alliance with Microsoft, the obvious victor. It turned out that there would be a few more episodes of this drama. We know about the effect of the iPod, iPhone and iPad, and also about Microsoft's remarkable retaking of the crown as the world's largest company last year. The latest laugh belongs to Apple, which is now the first company to be valued at more than $2 trillion. Its parabolic rise in the last few weeks helped bring the S&P 500 to a new all-time high:  This is a remarkable event. Silicon Valley was already well established as a global phenomenon back in 1999, but it continues to lead the world. The last few weeks have seen U.S. technology stocks reassert their ascendancy over peers in the rest of the developed world:  Meanwhile, Apple continues to be part of a phenomenon in which a few enormous internet platform companies, generally known as the FANGs, do far better than the average stock. The S&P 500 equal-weighted index, representing the average stock in the S&P 500, is still below a premature high made in June, while the NYSE Fang+ has moved into a new orbit:  So the record-high S&P 500 is also a narrow market. If a broader recovery lies ahead, this could be great news, as plenty of bargains remain to be discovered. It is as well to be careful with that kind of analysis, though. The FANG phenomenon makes it hard to apply traditional metrics to the market as a whole; but the FANGs don't drive everything. To illustrate this, see this chart from Steven Blitz, U.S. economist with TS Lombard. The biggest five stocks have a forward price-earnings ratio in nosebleed territory, but the remainder of the S&P is on a multiple of just over 20. The S&P 500 as a whole has only ever sold for a forward P/E above 20 for the two years leading up to, and then the two years immediately after the internet bubble of 2000, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.  As for Apple itself, the following chart shows its forward multiple, using Bloomberg earnings estimates, going back to the day it launched the iPhone in 2007, effectively ushering in the company's modern incarnation. With the exception of a few weeks at the end of 2007, Apple has never traded for a richer multiple of future earnings. Given how much growth is already priced in, and how difficult it will be to find any new product to act as a game-changer like the iPhone, this seems over-optimistic:  As ever, the riposte to all this is that interest rates are far lower now, indeed their lowest in history. All else equal, that justifies paying a higher multiple for stocks. Blitz has a response for this as well. There is no arbitrage between stocks and bonds; the difference in yields reflects the perceived difference in risk. When the economy looks more troubled, risk aversion will mean lower bond yields and a bigger gap with equities, and so on. He suggests that it makes more sense to compare the earnings yield (the inverse of the P/E) on a stock with the yield at which its credit sells. Investment-grade credit yields are also very low. On this basis, stocks look nowhere near as expensive as they did in 2000, when stocks paid a lower earnings yield than the credit yield. They do look as expensive as any time in the post-crisis decade:  For another disquieting indicator that this market has risen not wisely but too well, try the following chart from BCA Research Inc., which maps the S&P 500 forward multiple against the CBOE equity put/call ratio, showing the balance between those using options to protect against falls and rises in the S&P. Like valuations, the put/call ratio is in territory not seen since the internet bubble 20 years ago.  Apple is a great company. That doesn't mean it's a good investment. (For a comparison, try Cisco Systems Inc., which once traded at a multiple of 300; great company, abominable investment at that price.) FANGs and Mutual FundsThe FANG phenomenon is adding to the torture for active investment managers, as the latest report into U.S. mutual funds' holdings from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. illustrates. It is only possible to beat a narrow market like this if you grab on to a few of the big winning growth stocks and hold them. This is a problem, because the Russell 1000 Growth index, popular as a benchmark for mutual fund managers, is reaching record levels of concentration:  You can load up on lots of different value stocks, but a few big growth stocks can soon take up an unduly weighty share of your portfolio. This helps to explain why mutual fund managers are historically underweight in growth (just as it is doing so well), while overweight in value (which has suffered years of travails):  Specific and prudent limits placed on funds' concentration in particular stocks are causing severe pain. As Goldman says: AAPL, MSFT, and AMZN account for 10%, 10%, and 8% of the benchmark, respectively. Many managers face restrictions around diversification and position weights, making it challenging for them to hold the FAAMG stocks at their respective index weights.

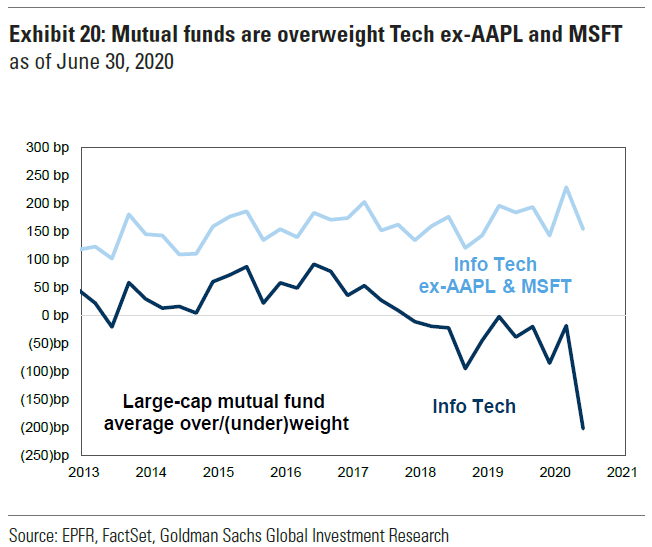

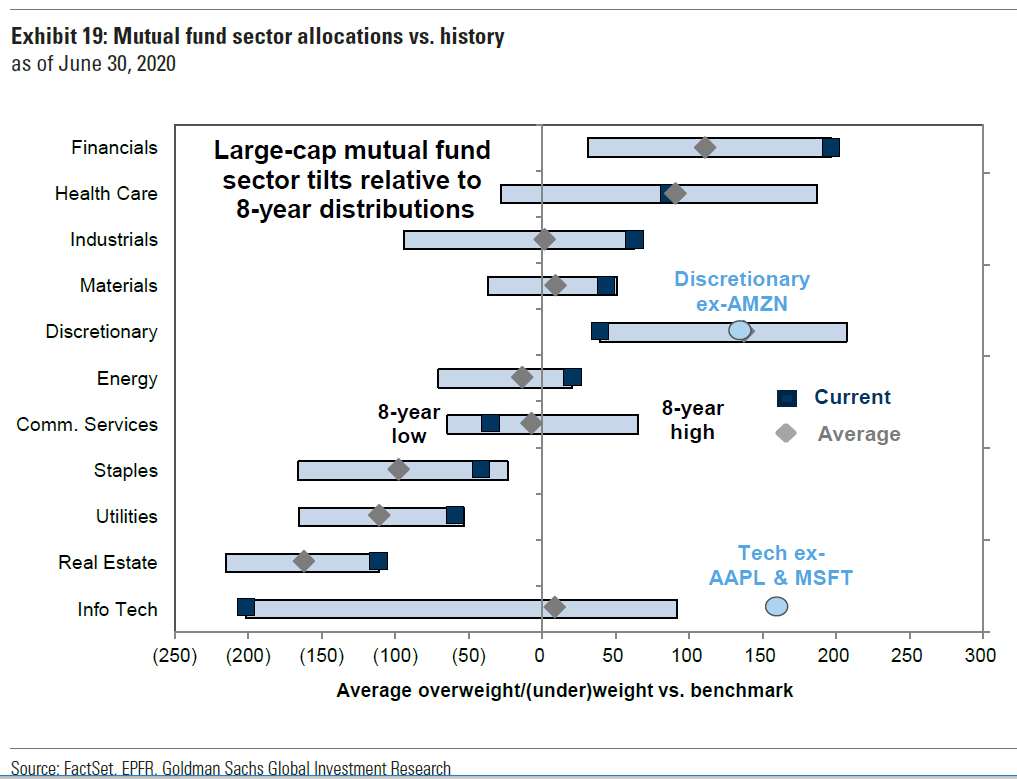

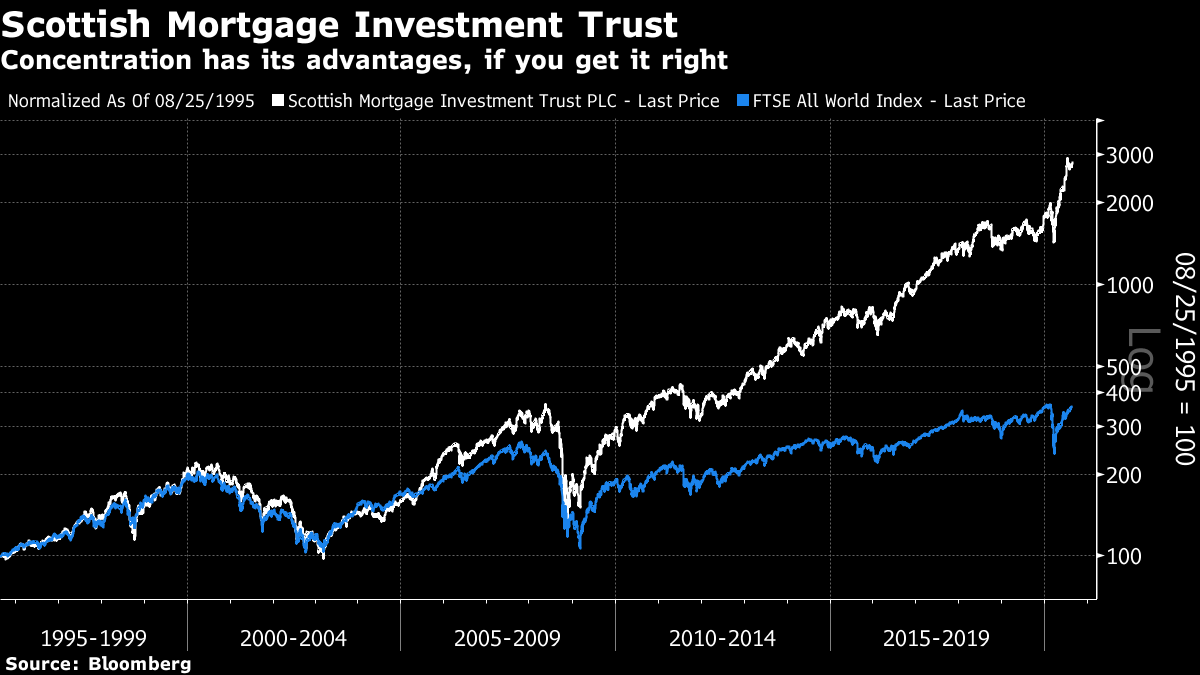

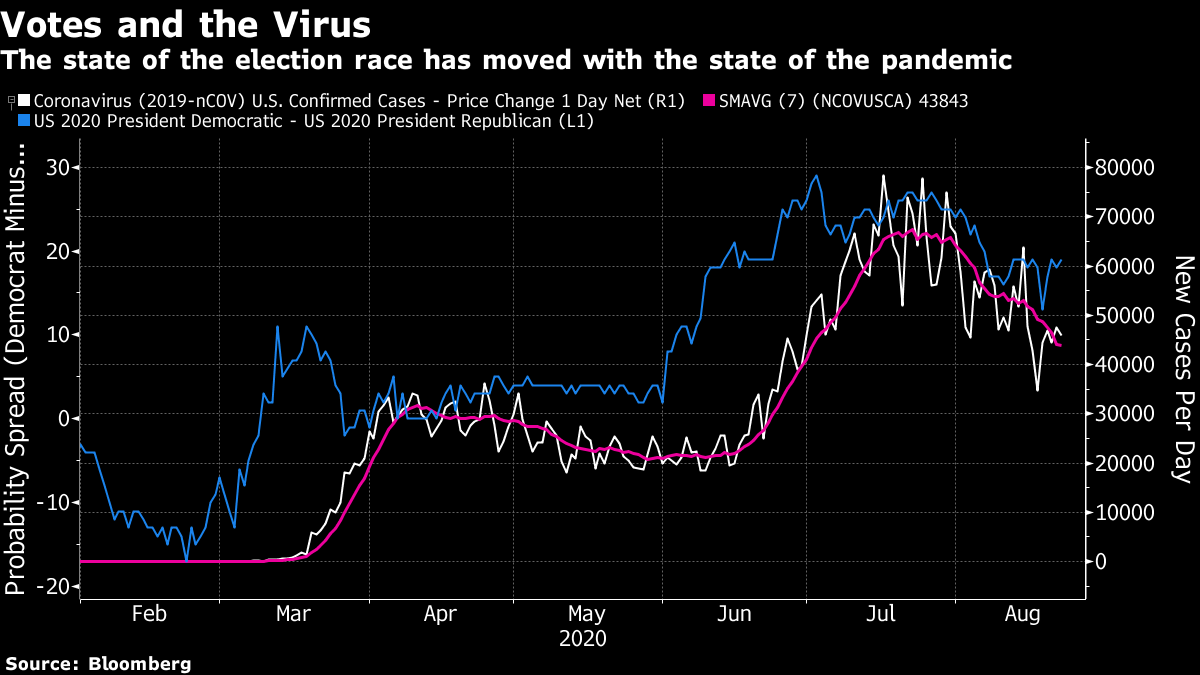

If the $3.5 trillion gorillas Apple and Microsoft are excluded, mutual funds are overweight in technology. Include the two pirates of Silicon Valley and, amazingly, mutual funds are significantly underweight:  A similar effect is at work within consumer discretionary stocks, skewed by the giant that is Amazon.com Inc. The current weightings to consumer discretionary and tech sectors are at eight-year lows. In both cases, this is entirely because of the FANGs:  Mutual funds could beat the index, at least in the short term, by jumping on the FANG bandwagon, but their own concentration limits won't let them. If you want to ride the momentum behind the FANGs, you will need a passive fund -- which, in this case, seems very poorly named. Passive funds are more heavily allocated to FANGs than ever, because the FANGs are a bigger proportion of the index than ever; active funds are less fully exposed to the FANGs than at any point in five years:  In the long run, this may turn out well for active funds. The concentration limits are there for a reason, and they are filling up on value stocks at bargain prices. By comparison, any number of passive funds begin to look like vehicles for speculation. This does, though, raise the issue of what the role of active management should be, now that passive funds are so important. With passive exposure to the market available cheap, it behooves active managers to be genuinely active, taking concentrated positions in stocks they have researched well. Rather than aping a broadly diversified index, maybe they should be allowed to let rip. For an example, I offer one of the most gloriously old-fashioned investment vehicles out there, the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust (which got its name in the 19th century and doesn't hold any mortgages). Its remit is to invest in international stocks, and it has done so uncommonly well. Here is its performance (in price terms) over the last 25 years, compared to the FTSE All-World index:  It has done this despite holding a very conservative 17.9% in cash. Among its 41 equity holdings, the biggest is Tesla Inc. (12.7%) followed by Amazon (9.4%), with Tencent Holdings Ltd., Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., Spotify Technology SA and Netflix Inc. all in the top 10. The fund has 41.7% of holdings in the U.S. and 17.3% in China. I suspect it will need to reshuffle these some time soon. But nobody can deny that it did a fantastic job of positioning itself for what has just happened. And with so much cash it even has plenty of opportunities to fill its boots at the next market break. If investment is going to be active, it needs to be as active as this. More conventional active mutual funds have found themselves in a no man's land this year, unable to match the low costs of index funds, but also unable to back convictions in the biggest growth stocks as much as some passive competitors can do. Little Bit of PoliticsA second week of intense political theater is in prospect as the U.S. Republicans prepare to nominate Donald Trump for a second term as president. Like the Democrats last week, the Republicans will have to hold most of their convention virtually, but they will doubtless find plenty of ways to give us thrills and spills, with the aid of producers used to reality television. Last week's convention seems to have stopped what was looking a steady erosion in Democrats' prospects, but not much more than that. A decent bet is that the next week will leave the race poised roughly where it was a week ago. Meanwhile, what really matters is the coronavirus. Whatever you think of the U.S. government's handling of the crisis, and whether or not the threat has been exaggerated, shifts in political sentiment this year have mapped closely against moves in new cases. Joe Biden and the Democrats are seen to have strengthened their prospects as the virus worsened, first in March and then again in early summer; and Trump's prospects have improved at times when the virus seems under control. On that basis, it looks as though we can expect a very tight election if the current fast-improving trend in cases should continue for another two months:  Survival TipsThe statistical claims and counter-claims on the virus grow ever more complex. You can find data to back almost any course of action, but I continue to think that a lot of the critical decisions that society and its leaders have had to make have been moral ones. The issues of how far we should go to protect each individual life, and what limits the state can put on individuals' freedom of movement depend on facts about the virus that we are still learning. They also inescapably require moral judgments. The latest book to offer guidance on this moral maze is Pandemic Ethics by the Australian philosophy professor Ben Bramble, and it can be downloaded free. I continue also to recommend The Ethics of Pandemics, an anthology edited by Meredith Schwartz of Ryerson University in Toronto, and not just because she kindly included one of my essays.I've seen research lately suggesting that lockdowns didn't work, and that we should have pursued "herd immunity" all along. Even if accurate, that creates moral dilemmas. For an exposition against the "techno-medical despotism" of quarantines and lockdowns, read this fascinating piece in the New York Times; and for an attack on the policy adopted by Sweden, which embraced herd immunity, read this impassioned piece by a disabled Swedish man, writing in a Danish newspaper. Even when we have the scientific facts straight, there are still difficult moral decisions to be made. We should make them as clear-headedly as we can.

Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

This Information is really good and informative. Thanks for it.

ReplyDeleteCheck below links and get useful information.

Auto Industry