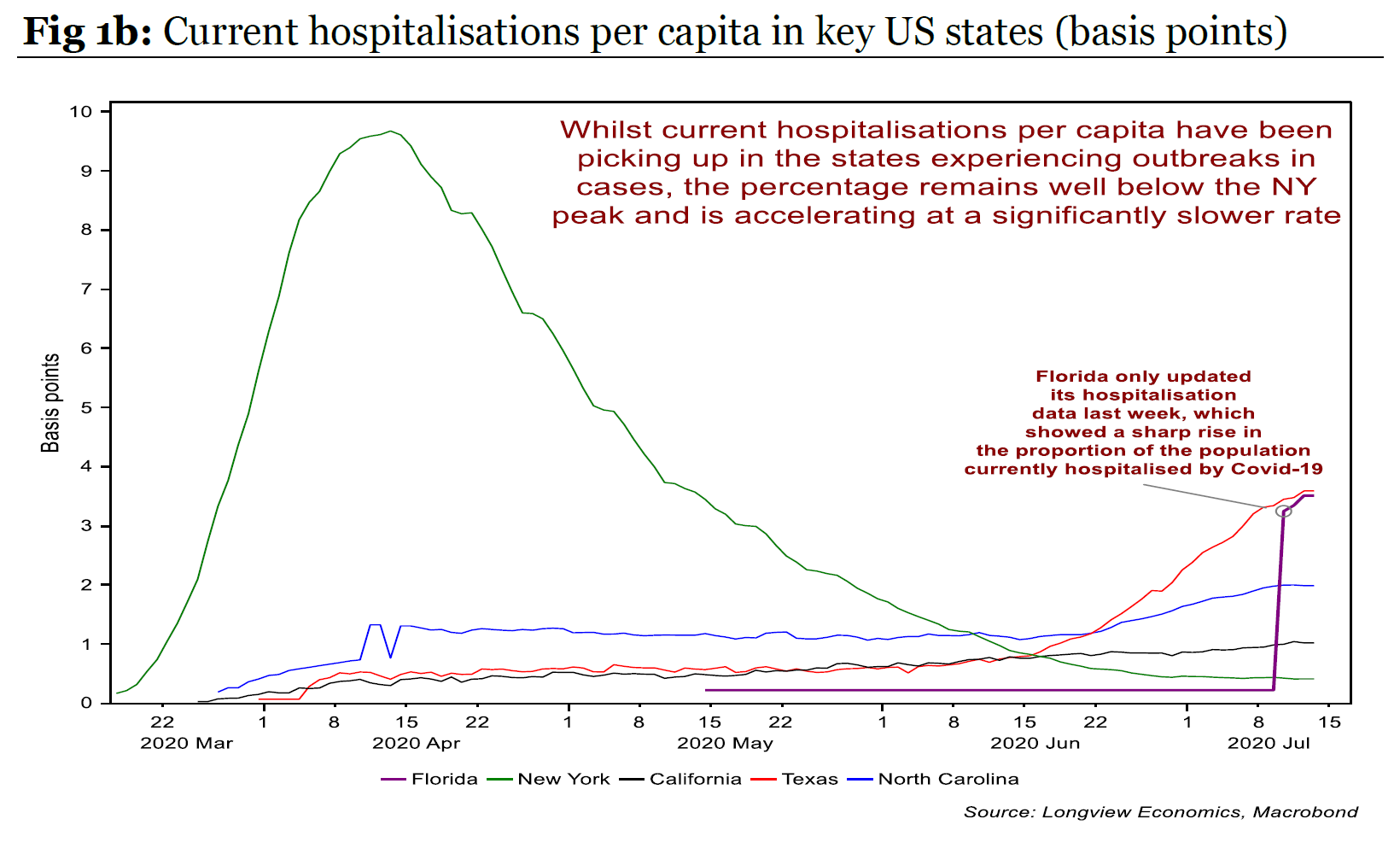

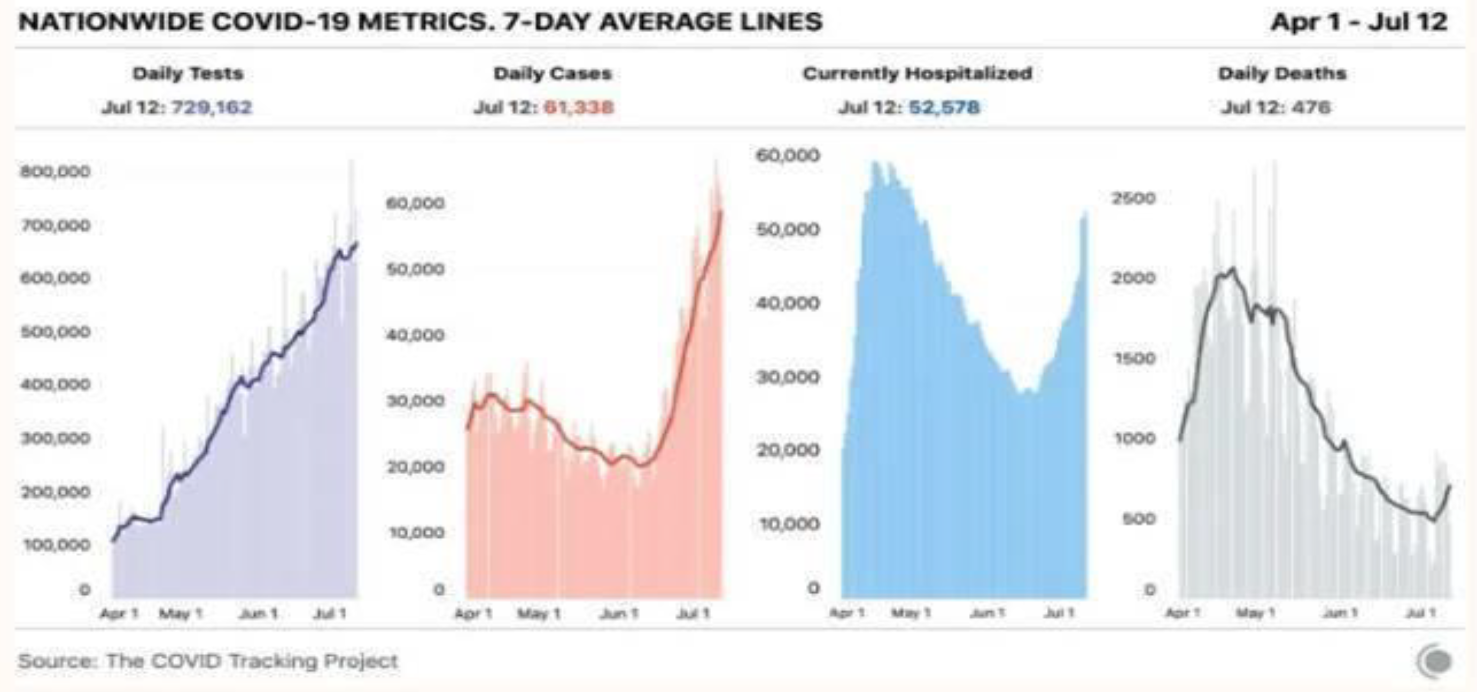

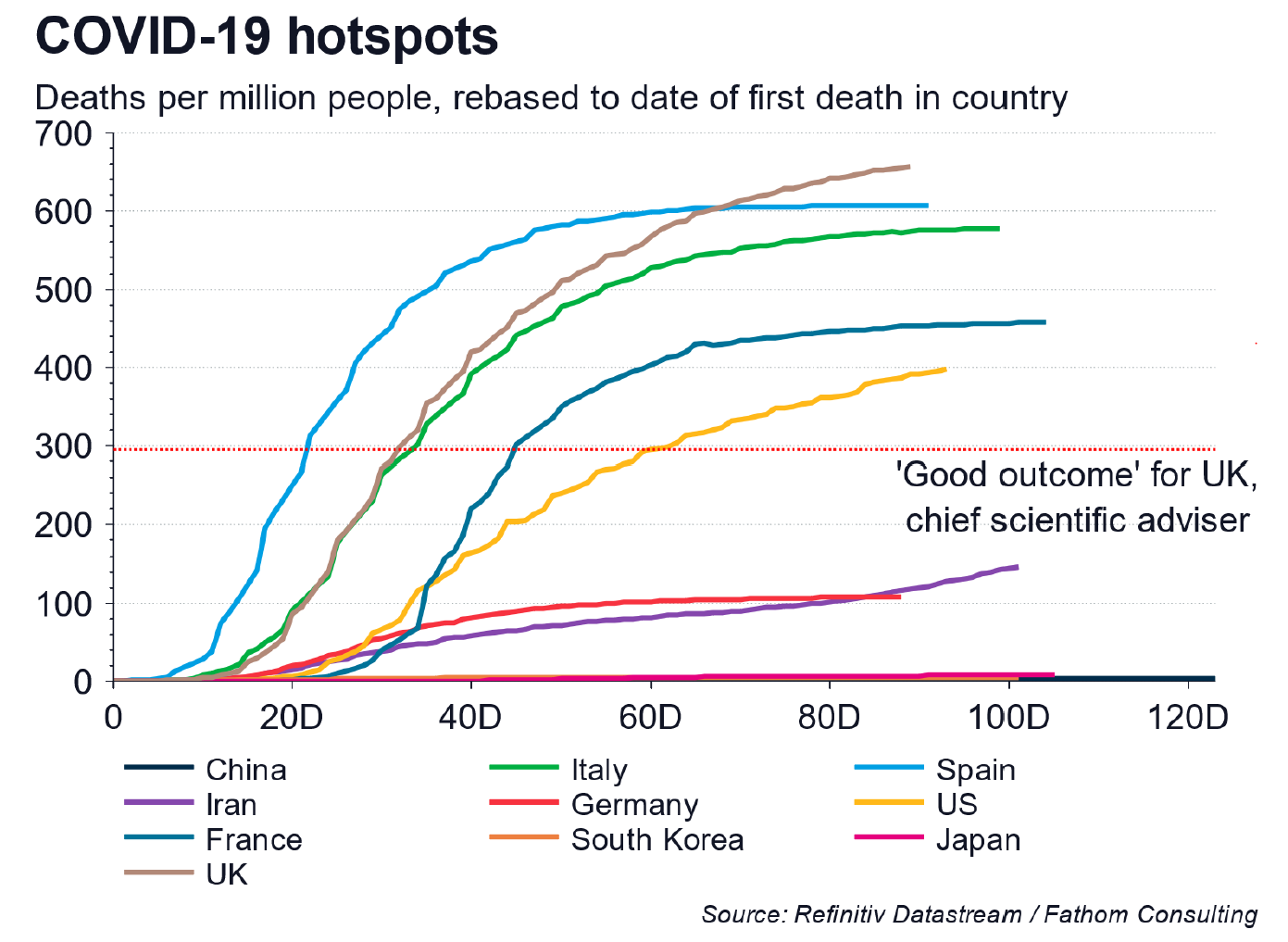

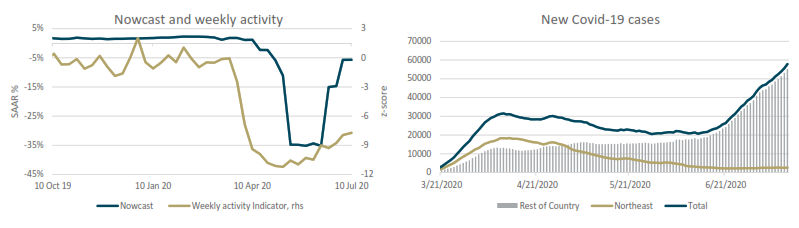

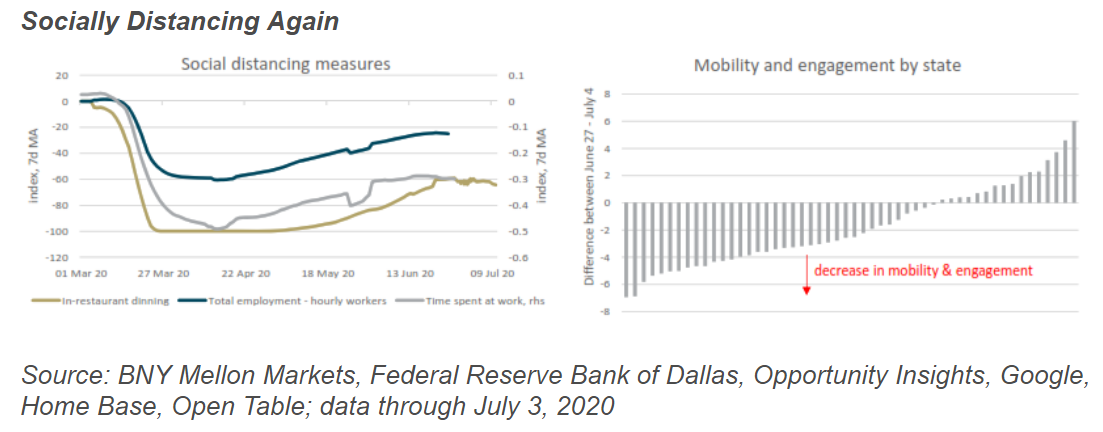

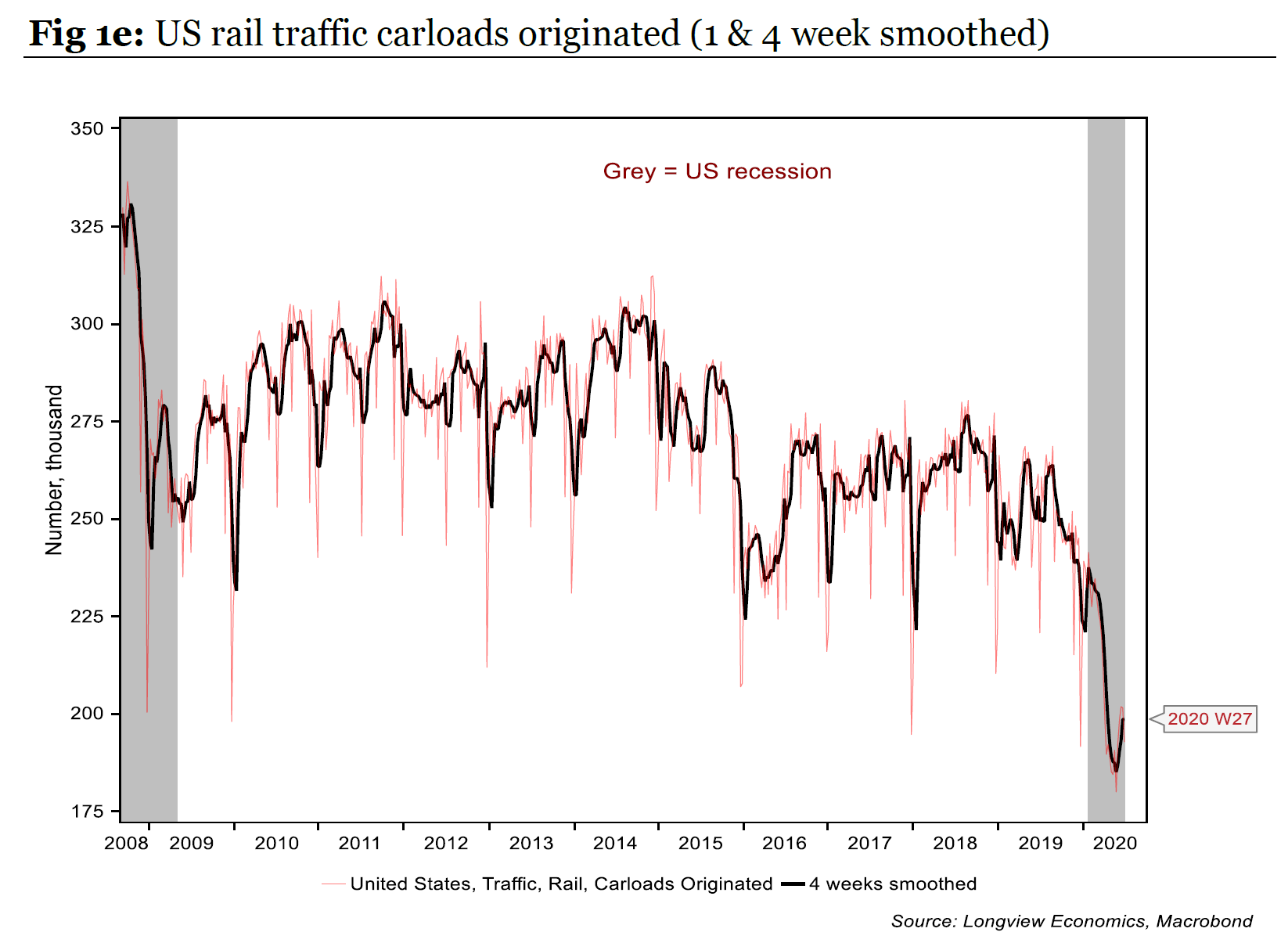

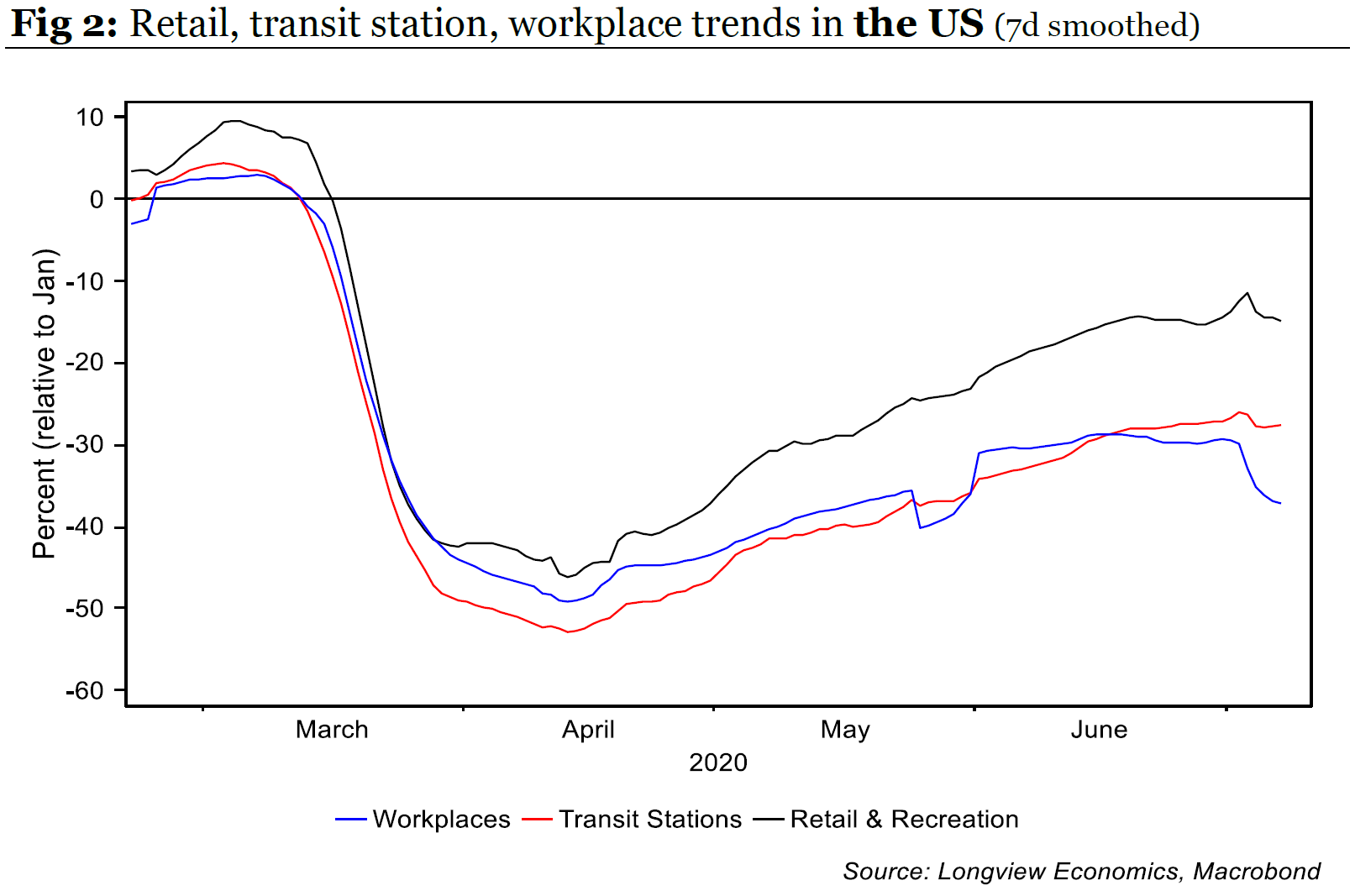

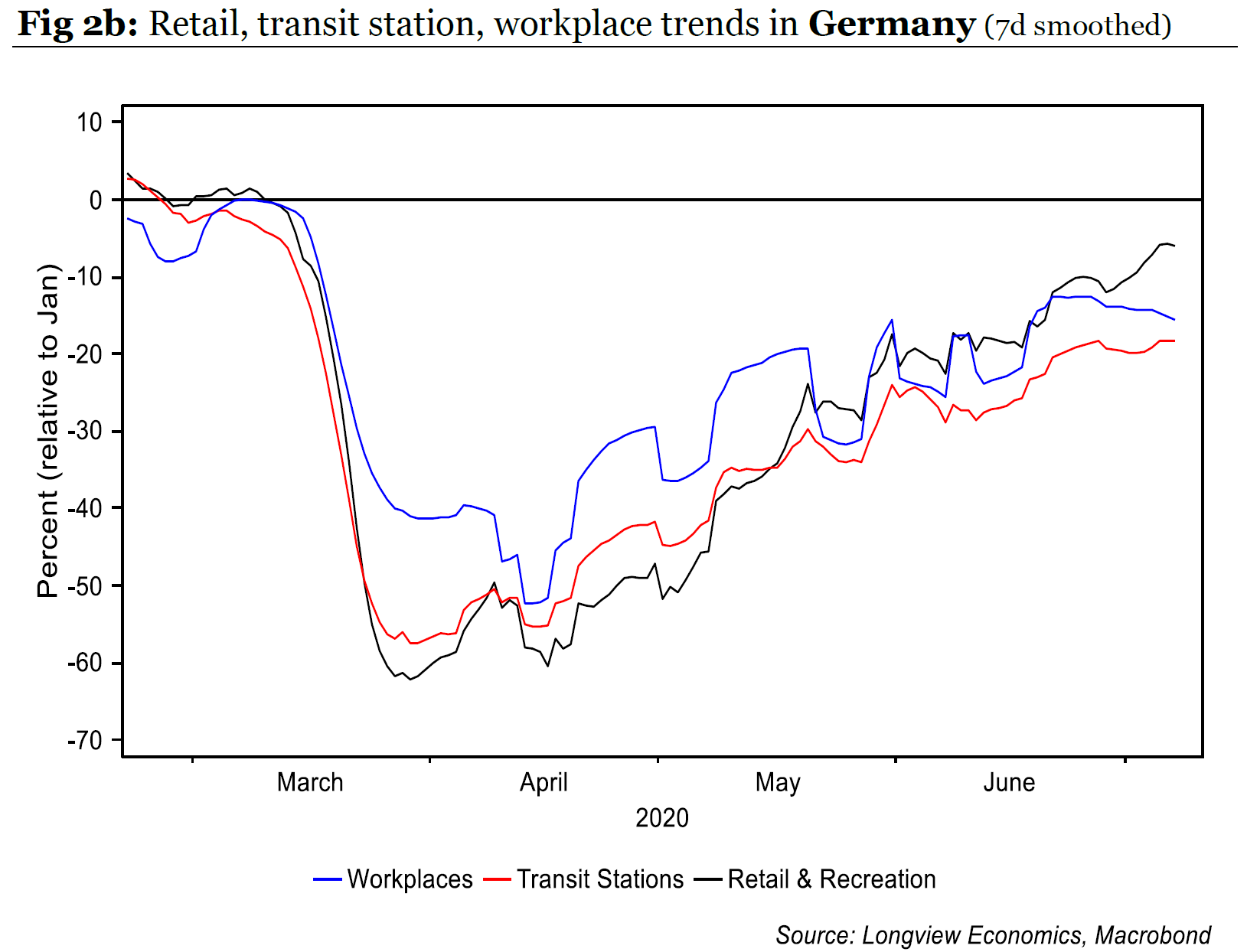

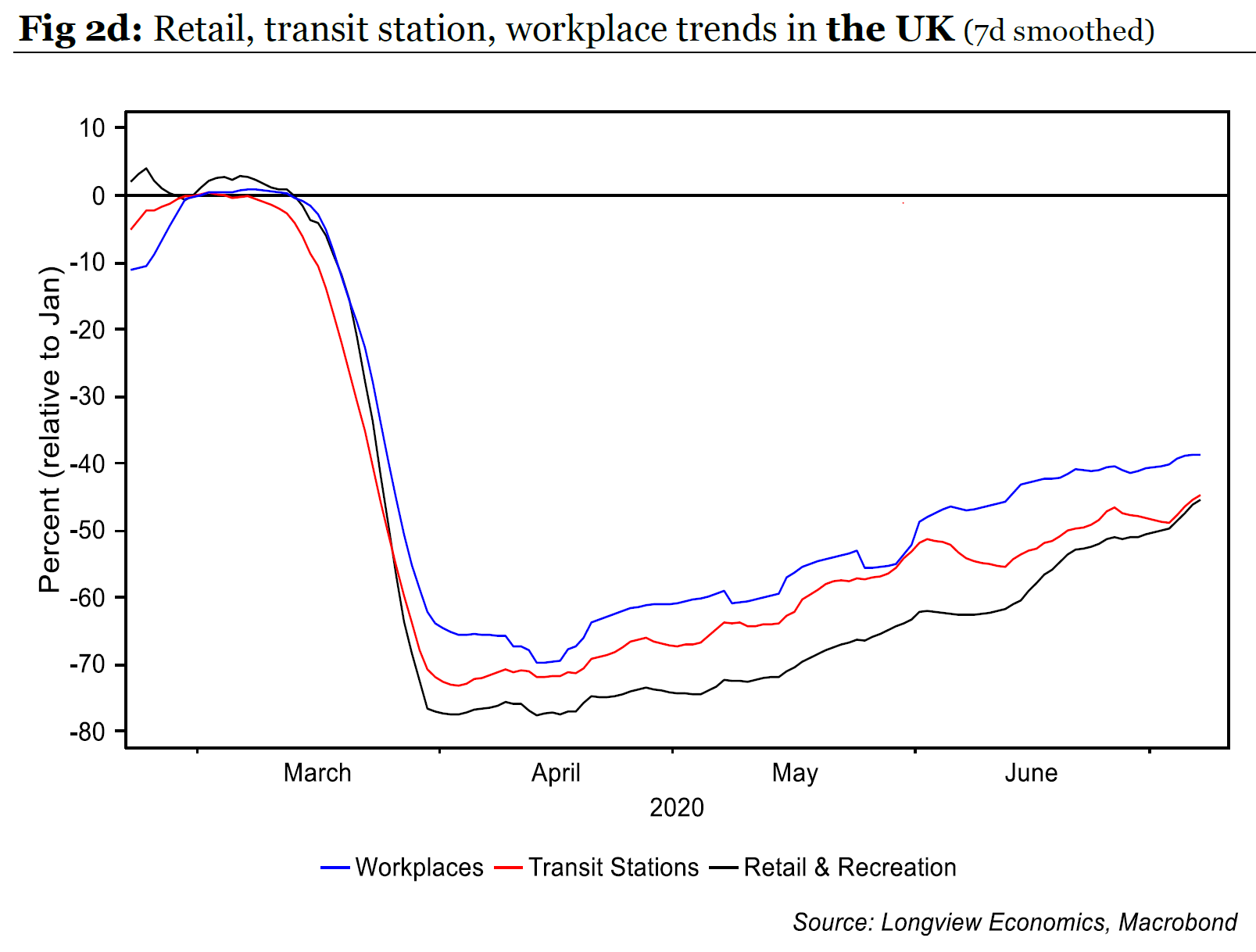

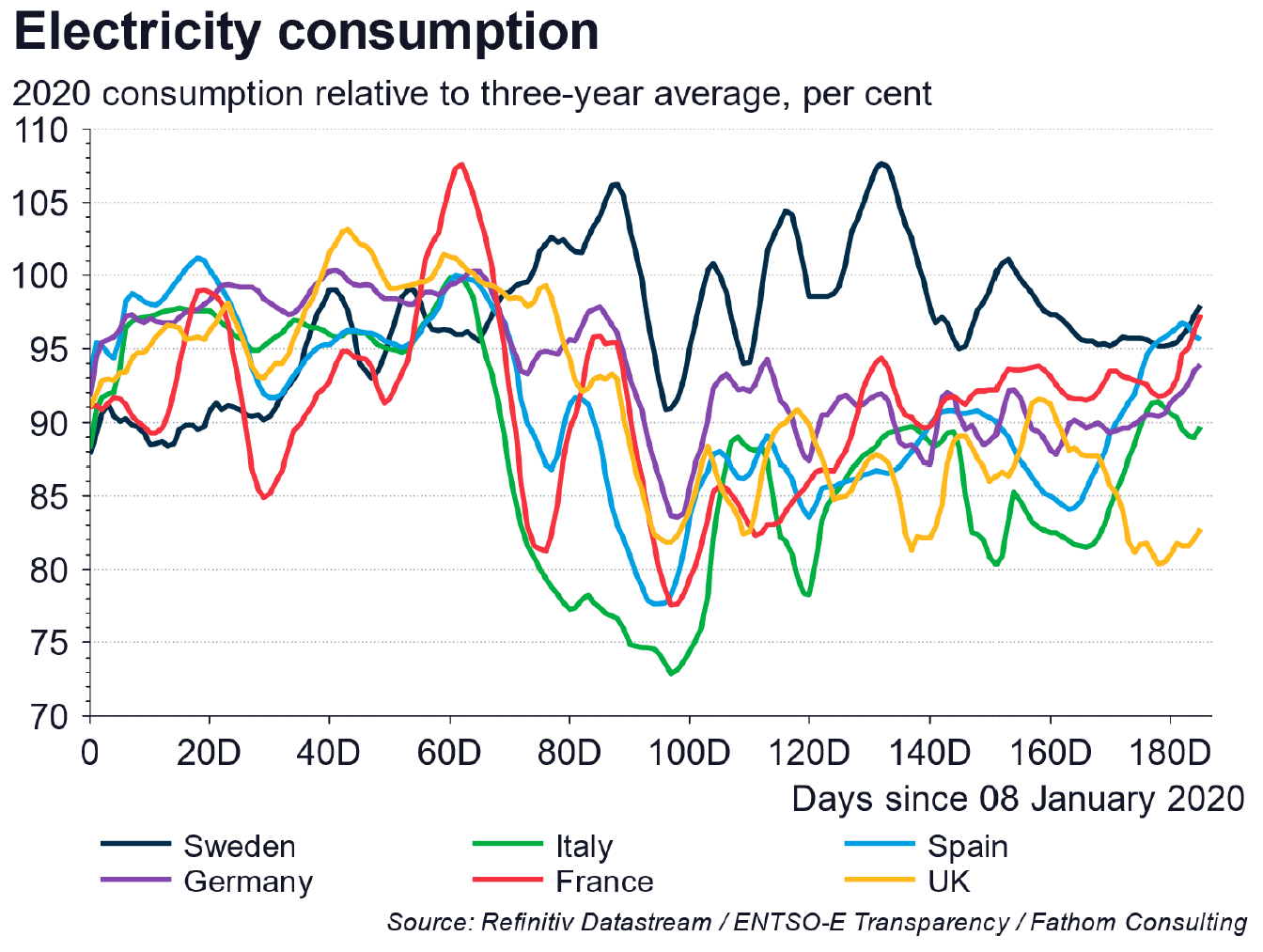

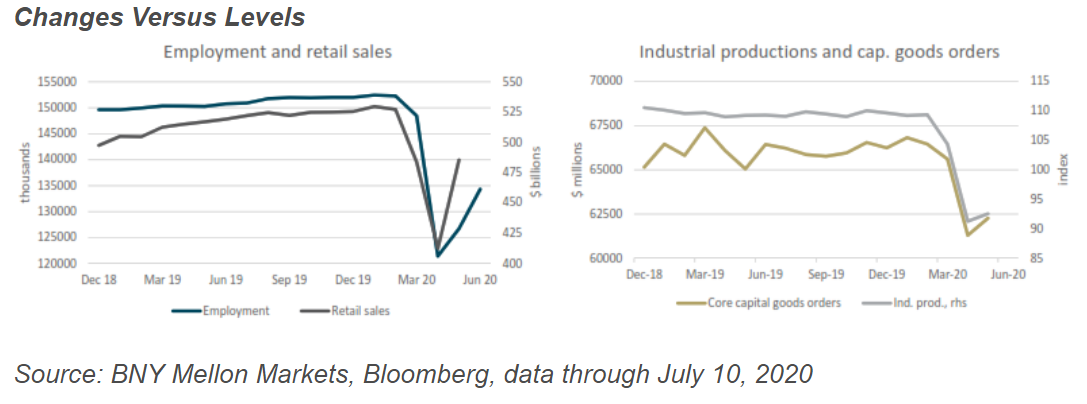

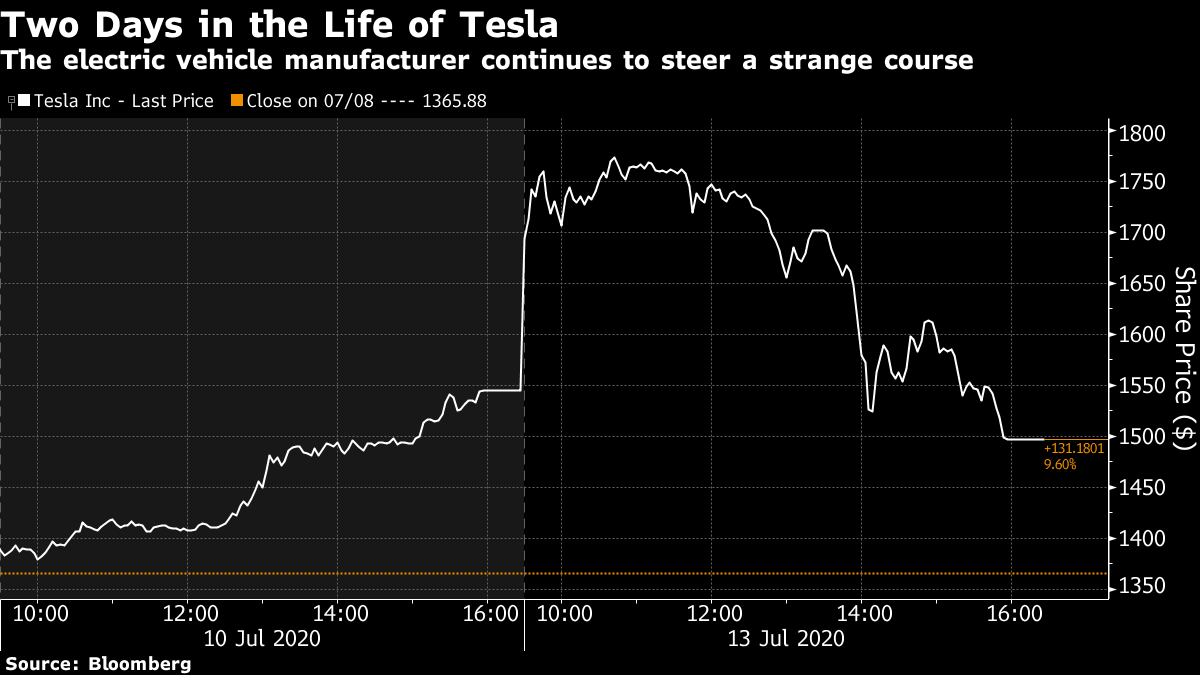

Inefficient Markets Monday wasn't a good day for the efficient markets hypothesis. The idea, you may recall, is that markets incorporate all known information at all times, and thus follow a trendless "random walk," jumping up or down according to the latest piece of news. Monday's trading in the S&P 500 certainly qualifies as "random" at first glance, charging upward, then suddenly reversing and ending down for the day. That is until two psychologically important lines are added. The S&P topped its level at the start of the year; surpassed last month's post-Covid high immediately after; and then, as though it had bounced against a hard ceiling, tanked:  The problem for random walk theorists is that prices are supposed to react to actual news. Neither of these landmarks qualifies. And this is the second time this has happened. Stocks reached positive territory for the year more than a month ago, and then staged a sudden retreat. It has taken until now to make another attack on the summit. If this sounds irrational, it is — although it is probably better to call it an understandable mental cue for more rational calculations. Doubtless there were algorithms programmed to sell if a new post-Covid high was reached. Beyond that, human judgments were involved. Confronted with the reality that stocks were up for a year in which there have been so many setbacks, investors looked for reasons to sell. Earnings season is about to get going in earnest, but it is obvious that the pandemic continues to dominate attention. Investment research firms are getting ever more ingenious at finding real-time ways to measure progress in fighting Covid-19, and also to measure the extent of the damage. Over the weekend, investors had a bundle of research that largely suggested reason for caution (although not despair). It seems to have taken this landmark for equity investors finally to confront what the Covid-19 numbers were telling them. Coronapictures Here follow my favorite Coronapictures from the last few days. They don't portray a disaster. They do suggest that driving the S&P to a positive return for the year is over-optimistic. U.S. Hospitalizations This chart from Longview Economics in London shows that hospitalizations, among the most reliable and important statistics, are rising in a range of large U.S. states — and that they remain far below the horrifying levels witnessed a few months ago in New York:  U.S. Key Metrics Longview's dashboard again gets across a worrying though not terrifying situation. Cases are shooting up with more testing, and the national death rate has begun to climb but remains much lower than it was three months ago. At the risk of the stating the obvious, this is both the most lagged and the most important data series — if the pick-up in the death rate were to prove the start of a trend, that would change perceptions profoundly.  International Comparisons Using deaths as the ultimate arbiter, this chart from Fathom Financial Consulting shows that a range of European countries have suffered worst, that the U.S. is rising alarmingly — and that the U.K. appears to have dealt with the pandemic worse than anyone else:  Economic Nowcasts How does this translate into economic activity? Bank of New York Mellon Corp. in an interesting report pointed out that even "nowcasts," using the most recent data on an array of economic variables, tend to be more than a month out of date. While they have shown a sharp improvement, weekly activity numbers, gleaned from a number of sources, present a far more muted upturn. Many investors are taking such activity data ever more seriously:  U.S. Mobility and Social Distancing Looking in more detail at BNY's activity data, we see that mobility is decreasing in more U.S. states than it is increasing, while steady improvements in measures such as time spent at work, and restaurant bookings, have stalled. (None of this will show up in any of the economic data published to date):  U.S. Railroads The problem of lack of mobility also shows up when it comes to rail traffic carloads, illustrated here by Longview Economics, a measure driven by industrial activity rather than any social distancing measures. Traffic has started to recover; it has a long way to go:  Mobility: International Comparisons There are good data now on how much people get to their place of work, how much they use transit stations, and how much they move around for retail and recreation. Longview distilled them nicely. The following three charts show the U.S. (which appears to have stalled), Germany (far closer to normality but also showing signs of stalling), and the U.K. (an unmitigated disaster):    Electricity Consumption: International Comparisons To ram home just how awful British economic performance has been during the pandemic, this chart from Fathom compares electricity consumption to its three-year average for a range of European countries. Sweden's contrarian approach to the virus seems at least to have avoided any serious loss of revenue for its electricity companies; the U.K. again shows up as a calamity, mitigated only by the potentially positive effects on the environment:  Changes vs. Levels One final point that BNY makes, about the U.S. data, is that it is easy to mistake changes for levels. The U.S. had a particularly sudden stop, which it didn't cushion as much as European countries with more expansive welfare states. That led to impressive percentage rebounds. But in employment, retail volumes, and particularly in industrial production, the U.S. economy remains a long way behind where it was pre-Covid:  Where does that leave us? The world is making slow and patchy but clear progress in dealing with the pandemic. Economic activity is similarly making only a halting recovery — it is strongest in continental Europe, terribly weak in the U.K., and very unimpressive in the U.S. Still, we are definitely in a better place than the worst-case scenarios that seemed reasonable to contemplate in March. If markets were really efficient as random walk hypothesists would suggest, we would have been witnessing mad fluctuations and volatility in response to every little data point of the kind I illustrated above. As markets are not in fact perfectly efficient, and tend to under- and over-shoot on waves of human emotion, a lot of these data were ignored until the market hit a big round number, and then everyone hurried to catch up. That's the way it works. Tesla's Random Advance Tesla stock had an interesting start to the week, gaining 16.2% in the first 15 minutes and then dropping 16.6% thereafter, to end down for the day.  Meanwhile, I have had plenty of feedback on yesterday's column, all giving me reasons why it is a great company that will do very well. None — as far as I can see — offer any numerical projections for revenue and profit. The key point, made over and over again, is that Tesla shouldn't be regarded as an auto company, even though at present its revenue is almost completely dominated by cars. It is far more disruptive than that; has a "million-mile battery" in the pipeline; and isn't taking over the auto industry, "it's taking over the transportation industry," I am told. To quote another glorious piece of feedback: "I'm not sure it would have mattered if the whale oil producers of 150 years ago outspent Thomas Edison on R&D when he invented the electric light bulb. If you don't think combining solar generation, electric battery technology, electric vehicles and self driving are a bright idea then you might be missing what many people are starting to realise." It's my job to be skeptical. I don't think it makes sense to price Tesla at this point on the assumption that it takes over the transportation industry. The fact that it is so ambitious, and that it is so difficult to put a price on what those ambitions might yield in monetary terms, explains neatly enough why it is in the grip of such speculative fervor. As with the youthful internet companies two decades ago, it is obvious something exciting is being built — but not so obvious how it will pay, how far it will go, and who will profit. Naturally, valuations will be all over the place. That leads me to one comparison that gives some backing to what Tesla's backers are predicting: Amazon.com Inc. That disrupter, you may recall, started life as a "virtual company" that would be a pure intermediary with no physical assets to speak of, and was initially a mail-order bookseller. In that capacity it quickly reached an absurd valuation, and spread into many other product lines, all the while losing buckets of money. But 10 years after going public, in 2007, it was beginning to show that investing at the beginning wouldn't have been such a bad idea, as I wrote in this piece following its 10th anniversary. It was almost back to its bubble-era high, and had emerged as a company whose critical advantage was its physical infrastructure. At this point, hardware such as Kindles lay in the future, nobody had ever asked a question of Alexa, the idea that Amazon could become a dominant player in cloud computing had occurred to nobody, and certainly nobody thought it would buy any actual grocer. In the following chart, which is on a log scale, I have indexed Tesla and Amazon so that they start at 100 on their day of IPO. Tesla's trajectory is remarkably similar.  If Tesla can keep tracking Amazon over its next decade or so, then plainly it is a "buy." Can anyone really be certain of that? No. It is possible, but unlikely, just as the last 13 years for Amazon were possible but unlikely back in 2007. An investment in Tesla offers no margin of safety. But its followers believe that it is the new Amazon, and if they're right then there are profits ahead. Survival Tips The film of the musical Hamilton is now available for streaming on Disney Plus. It was filmed beautifully and watching it adds greatly to the experience of seeing it in the theater. You can subscribe to Disney Plus, watch it every night for a month, and then cancel your subscription; I recommend doing just that. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment