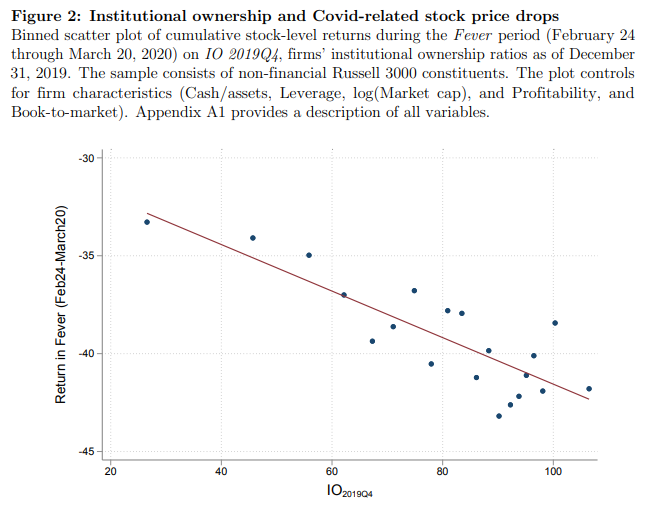

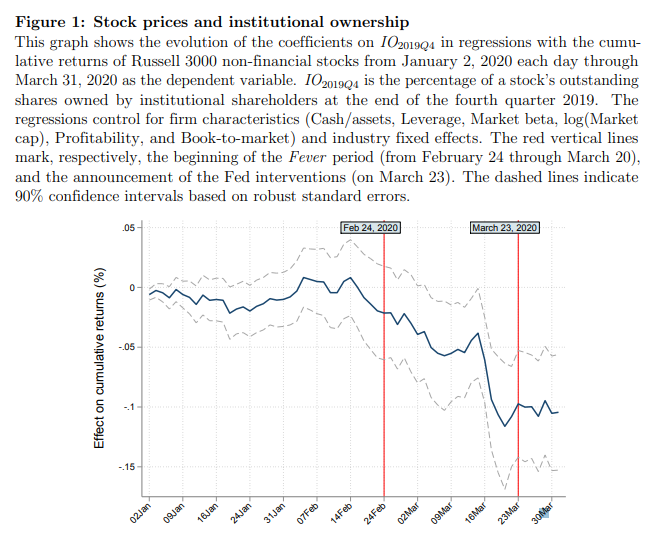

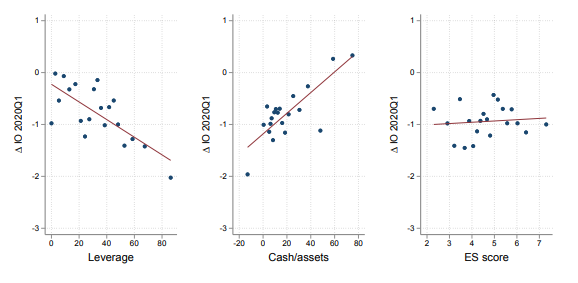

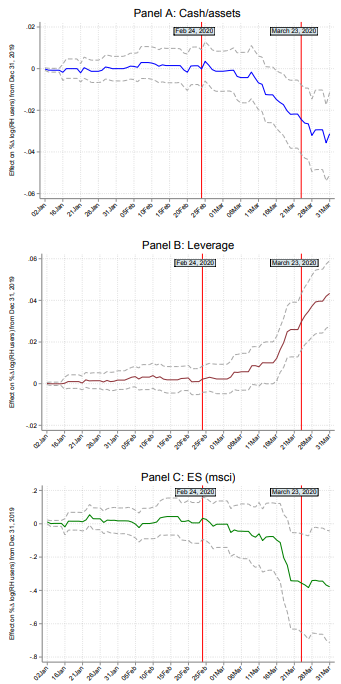

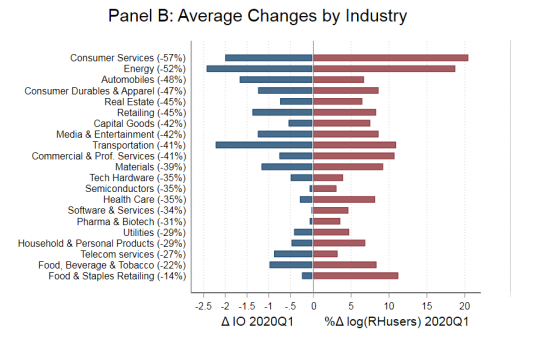

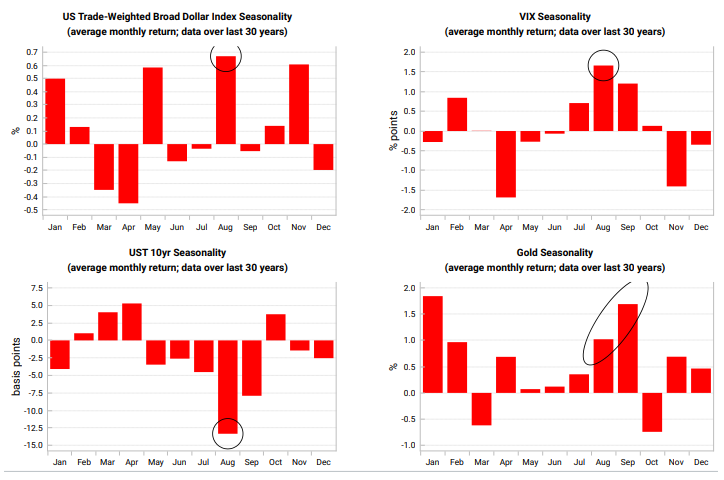

If You Can Keep Your Head… When the chips are down, is institutional money any more patient than the money the rest of us put into the stock market? Over the past few decades, the game has changed. It is no longer about rich individuals investing their own funds for their own benefit, but about big institutions, trading in such a way as to convince people to entrust them with more money. In theory, the institutionalization and professionalization of investing should make for steadier, less excitable markets. But when Covid-19 gave everyone a truly exogenous and serious shock in the first quarter, we learned different. A new study shows that the stocks most heavily held by institutions entering the crisis tended to have the most volatile and negative reaction. And, amazingly, it was the new and much-publicized breed of retail investors who appear to have got on to the right side of the trade and made money. The study, by Simon Glossner and Pedro Matos of the University of Virginia and Stefano Ramelli and Alexander F. Wagner of the University of Zurich, is available here. I will try to give you my best summary of the results, without getting into the statistical thickets. First of all, the more a stock was held by institutions (shown on the horizontal axis in this chart), then the more it fell during the "fever" sell-off period from Feb. 24 to March 20 (shown on the vertical axis). The chart aims to control all the other variables that might have affected returns:  The following chart puts the same information a different way, and shows how stocks with the greatest institutional ownership tended to perform this year, all else held equal. The dotted lines show the confidence bands around the main result:  What did institutions buy instead? The following chart maps the change in their preference for companies with high leverage (or weak balance sheets), companies with high cash as a proportion of assets (or strong balance sheets), and companies with good environmental, social and governance, or ESG, scores. Wholly unsurprisingly, they dropped over-leveraged companies like hot potatoes, and bought stocks with strong balance sheets. Somewhat surprisingly, given the popularity of ESG funds at present, they made no particular move toward companies that looked good on these criteria:  Why were institutions so desperate to get out? They may be more susceptible to groupthink. People running money at big institutions tend to know each other, and use the same information sources, having gone to the same schools and studied the same curriculum. But perhaps their motivations are most important. An institutional money manager is often primarily concerned with holding on to assets under management. That means not looking embarrassingly bad compared to the competition. Losing money per se isn't so much the problem. Such factors seem to have contributed to this latest sell-off, and suggest that the professionalization of investment may have made markets less rather than more stable. Someone must have bought the stocks that the institutions sold. An analysis of the most popular stocks among Robinhood discount brokerage members suggests that it was indeed the merry men. This chart shows the popularity with Robinhood investors over time of strong and weak balance-sheet companies, and ESG stocks. During the "fever" crisis period, shown by the two red vertical lines, they lost interest in strong balance sheets, and went all out on highly leveraged stocks. They also seem to have lost interest in ESG stocks.  Perhaps most impressively, the researchers broke down average changes by industrial sector, for the entire first quarter. The inverse correlation is stunning. For every sector, institutions reduced their exposure, while Robinhooders increased theirs. Given what happened in the second quarter, we can assume this worked out better for the merry men:  Some of the Robin Hood decisions, such as piling into energy as it collapsed, look a tad reckless; but energy had the best return of any sector in their second quarter, so even that worked out well for them. At this point, some will complain that Robin Hood isn't as powerful as all that, and is over-hyped. This is true. There is no way that Robinhood.com users could absorb all the liquidity created when institutions ran for the exits. But note that Robinhood.com is being used in this case because it produces good data that allow academics to do some interesting studies. It is a reasonable "ball park" assumption that trends for the other large discount brokerages would be largely similar. Retail investors tended to show similar group behavior way back in the late 1990s when people in the financial press last had to follow their every move. Not only is the retail investing phenomenon bigger than Robinhood.com, it is also bigger than America. The following collage comes from the weekly newsletter provided by Peter Atwater, of the Financial Insyghts consultancy:  China has had more than one incident of retail-driven over-enthusiasm in the last two decades, while South Korea, where small investors have always had an unusually keen eye for options trading compared to other countries, and even Russia also have growing armies of retail investors. You can view this as a phenomenon driven by global distrust of elites and authority, or a reaction to the pathetic interest rates available on savings rates almost anywhere. But the point is that retail investing needs to be taken seriously, even if the most visible Robinhood.com traders tend to be ridiculous to the point of self-parody:  Where this could lead is harder to tell. The most appealing narrative casts BlackRock Inc. as the Sheriff of Nottingham and Robinhood.com as Robin Hood. Channeling Rudyard Kipling's stirring if rather sexist poem "If," they kept their heads while all about them were losing theirs. They also up-ended the stereotype from the late 1990s, when regulators anxiously watched the money piling into retail accounts and worried about the possibility that it would all be taken away at once. In the event, retail investors kept buying on the dips of the late 1990s, and generally kept holding on the way down in 2000 and 2001. On a number of occasions it appeared that they had rescued the market and proved the smart money wrong. In the final analysis, many of them wished they hadn't got so involved. But there are risks. One is that if prices take another sharp downturn it will be the retail investors who are left holding the baby this time. That would only contribute further to inequality and the deep sense of injustice around the world. As the merry men have piled into companies with bad balance sheets, they are exposed to a looming solvency crisis. And as ever there is the fear that they are part of an irrational mania. There is an alternative version of "If," which begins: "If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs, you have probably failed to grasp the seriousness of the situation." Summertime, and the Trading's Not Easy…. August is almost upon us, and the northeastern U.S. is now uncomfortably, not to say disgustingly hot. Even if it is harder for people to escape on vacation this year than usual, it seems reasonable to expect markets to give us a dose of calm for the next few weeks. Unfortunately, history suggests that Augusts aren't always that sleepy. This chart, produced by Variant Perception with Bloomberg and Macrobond data, shows average monthly returns over the last 30 years for a range of assets:  August turns out to have been the best single month for the VIX volatility index and for the dollar, and the worst month for 10-year Treasury bonds (meaning yields tend to go up). It is also the best month after January for gold. Why so many fireworks amid the blue sky of summer? Part of it is down to the coincidences of history. I started my career in financial journalism in 1990, when August brought Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait. The following August saw the Russian coup that eventually brought down Mikhail Gorbachev, and the Soviet Union with him. Other August surprises since then have included the Russian debt default in August 1998; the run on Countrywide and the first interventions of the credit crisis by the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve in 2007; the debt ceiling crisis and Standard & Poor's downgrade of the U.S. in 2011; the Chinese devaluation of 2015; and last year's shocking acceleration of the trade war between U.S. and China. Take thinner summertime volumes, and a dose of complacency, and such shocks are likely to have a bigger effect. What are the chances of something similar this year? All the events I mentioned were genuine shocks. It isn't sensible to predict the chance of a surprise of that magnitude. But with the dollar tumbling on a sense that the next wave of dollar weakness is with us, Treasury yields firmly anchored at historically low levels, and the VIX back to its lowest level since Feb. 24 (albeit still rather elevated compared to the average for the last five years), all of these markets are well-positioned for a repeat of their typical August behavior. In other words, in response to a shock of some kind, Treasuries have a long way to fall, and the VIX and the dollar have a long way to rise.  September, and with it Labor Day and the beginning of the U.S. election campaign proper, can look a little ominous from here. The political calendar, and the potential for a seasonal second wave of the virus, could obviously send things awry. But Augusts are dangerous. We may be glad when the dog days are over.

Survival Tips

Bedside reading, or perhaps sometimes bathroom riding, is a must for survival. Such books need to be readable from any point, and then put-downable at any point. You don't need to start at the beginning of a chapter, and you don't need to read in order. (Habits that are harder to follow with an e-reader.) You just dip in. With attention spans shortening as the summer and working from home drag on, let me offer two excellent candidates. First, there is "Life" by Keith Richards, who amazingly was still alive in 2010 to write it. More amazingly, he could remember much of his life. And totally extraordinarily, he's still with us. The book is born of an artful collaboration with the ghost writer, so that it's knitted together beautifully, but with great chunks of wisdom and anecdote from Keef himself, presumably re-told on the written page just as he said them in conversation. He also frequently offers other characters in his life story, including his son Marlon, to write large discrete passages that are neatly inserted into the dialogue. Any accurate telling of the life of the Rolling Stones' guitarist will necessarily be disjointed and double back on itself, so it's ideal for dipping into. It helps that the Stones' story is nowhere near as well-known as the Beatles'; it turns out that Jagger and Richards' first song written together was As Tears Go By, and they only wrote it after being locked in a kitchen. Also in a musical vein is "Songbook" by Nick Hornby, the writer of "High Fidelity" and "Fever Pitch." "Songbook" is a collection of essay about songs that Hornby likes, illustrated with cultural references and digressions. There are essays on 31 songs; I had heard of two before I started reading. He even managed to pick a Beatles song I hadn't heard (Rain, a Revolver-era song that was plenty good enough to have been on the album). Some are gems like I've Had It by the underrated Aimee Mann, or a reggae version of Puff the Magic Dragon. Both of these were left by some good soul on the old bookshelf on a street corner that functions as our neighborhood book exchange. Book exchanges are a great idea. And bedside reading is essential for survival. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment