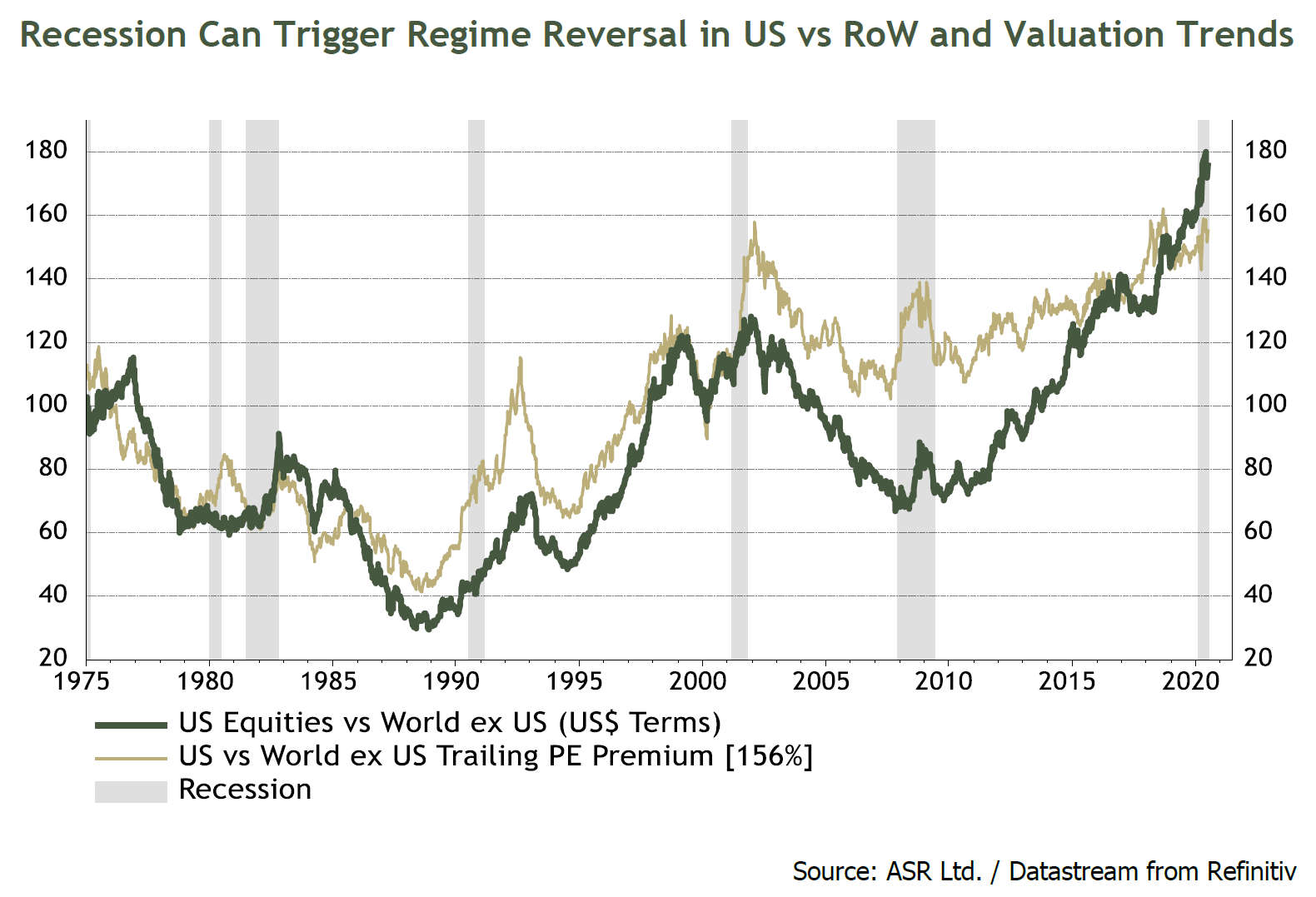

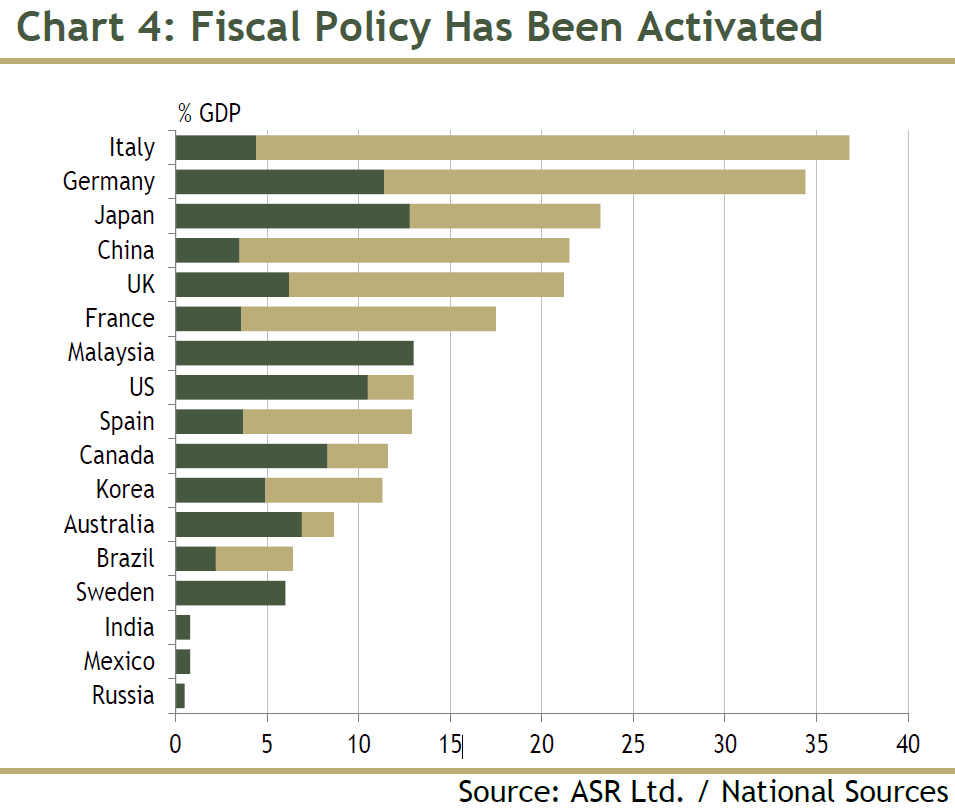

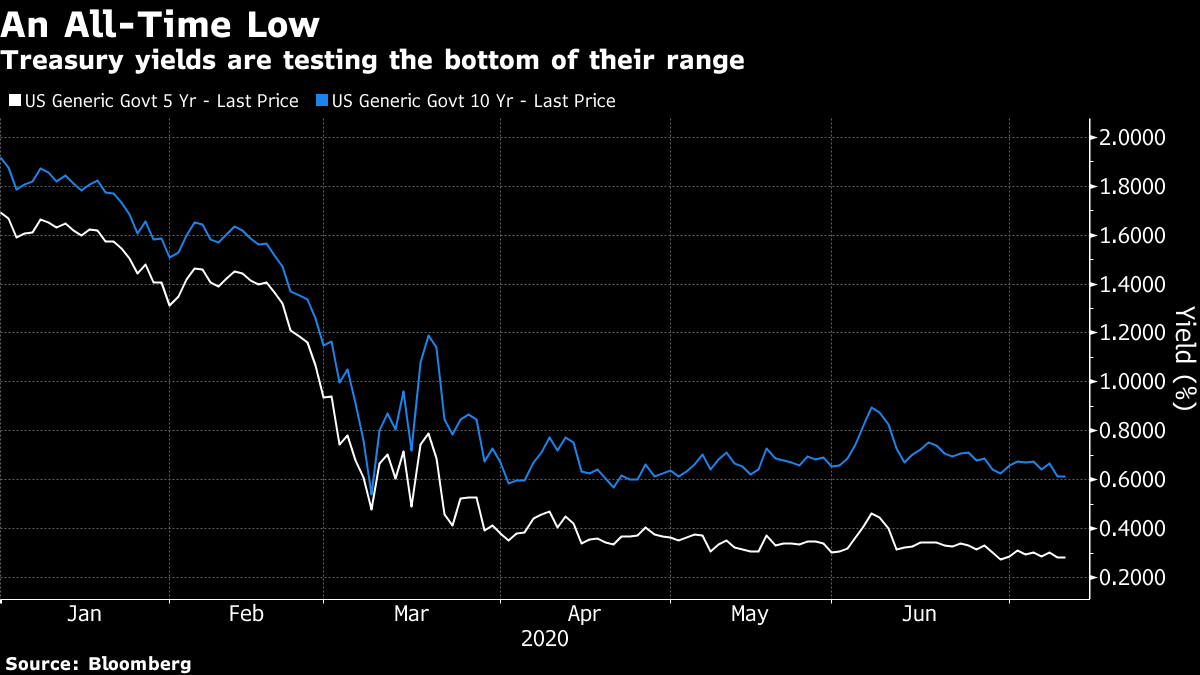

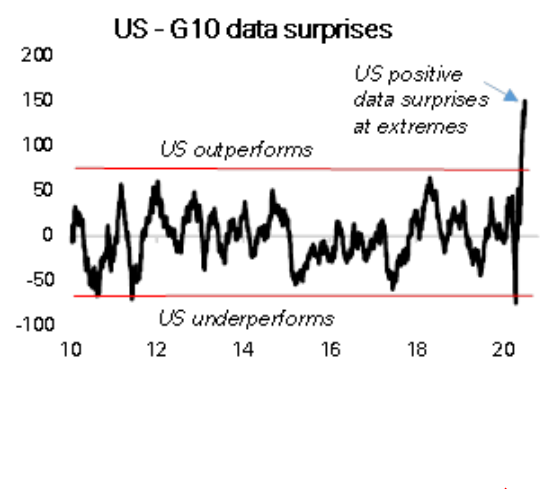

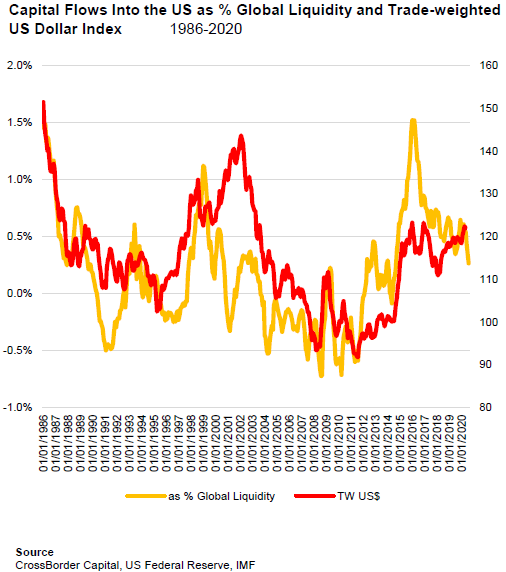

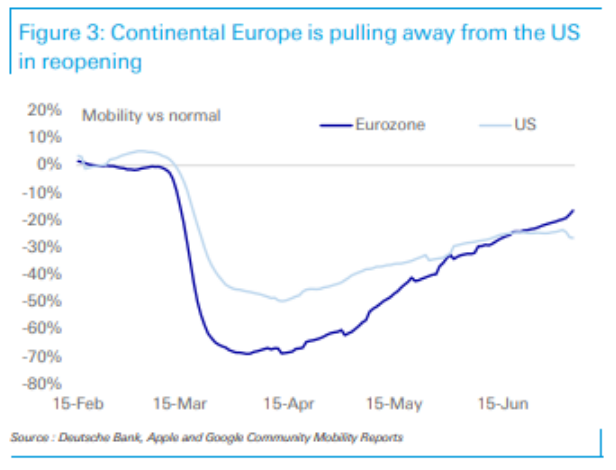

Regime Change It is time for the investment regime to change. That is what happens after a major international financial crisis, and we certainly had one of those earlier this year. We also have a remarkably strong and persistent ancien regime, which has lasted ever since the last crisis and is in need of change. Rates and inflation have been low, inequality has grown, and American assets have massively and consistently outperformed the rest of the world. This chart from London's Absolute Strategy Research, Ltd., makes clear how strong the current regime is, and how prior recessions led to new regimes:  The previous crisis came shortly after the total value of European equities, as calculated by Datastream, had overtaken that of the U.S. In hindsight, that was a good signal that trends had been taken too far. But what is needed to ensure a change this time? The current regime has been characterized by a series of pathologies we have all grown to recognize. Ian Harnett and David Bowers of Absolute Strategy summarize the economy's "underlying conditions" and health status as follows: It is complex because of 'multiple comorbidities' (to use a medical term). The global economy already had 'underlying health conditions': for a start it was old - and late cycles are typically when multiple 'excesses' build up. This cycle is no different and has its fair share of excesses: excess corporate debt, excess dependence on USD liquidity, excess reliance of Russia-Saudi cooperation to support the oil price, excess confidence in 'Alternatives', and excess faith in the cult of the share buyback and in equity income more generally. And it is in complex recessions that the policy 'rule book' tends to get torn up. In addition to this, we appear to have a change of direction in policy. Monetary policy has remained exceptionally easy for more than a decade (even if various central banks made attempts to exit at different times). Fiscal policy, after China's initial stimulus in 2008 and the rather half-hearted stimulus that followed in 2009 in the early days of President Barack Obama, has been quiet. That now is changing, on a global basis:  A third reason, which also makes eminent sense, is that governments will want to play a greater role in the economy now, after taking direct stakes in so many companies. The pressing need to deal with the problem of growing inequality before it boils over into civil unrest and ungovernability also likely points to more government involvement. A less laissez-faire, more statist version of capitalism means less in the way of the tactics connected to "shareholder value," such as share buybacks or private equity buyouts, and also points the way toward outperformance by a different array of countries, rather than the U.S. Under a new regime, we can expect to reverse many of the orthodoxies of the current one. Value can at last beat growth, banks can start to outperform the rest of the market, foreign exchange volatility can come back, as can inflation. And as fiscal policy tends to be more specific to individual countries than monetary policy (money can flow overseas, but a new highway tends to stay where it is), we can also expect more geographical divergence between countries. And we can expect cheap markets (virtually every stock market on earth other than the U.S.) to start outperforming expensive markets (the U.S.). But, as Donald Rumsfeld discovered after the invasion of Iraq, regime change is sometimes not as simple as it appears. The two prime "known unknowns" that could mess up this scenario are as follows: The Dollar A weakening dollar would allow emerging markets in particular to take wing once more. The sharp rise in the price of gold, and the recovery in the oil price, should both help to weaken the dollar. But the dollar is not giving up and falling as many expect. Against developed markets, as shown by the popular Dollar Index, it is marginally below its long-term trend: and against emerging market currencies, the dollar still seems very strong:  What could change this? Perhaps most importantly, the bond market gives grounds for dollar weakness. U.S. bond yields fell again on Wednesday, bringing the five-year Treasury yield to a new all-time low, while the 10-year yield came close to dropping through 0.6% for the first time since April:  Beyond suggesting that the bond market takes a very gloomy view about growth prospects, the U.S. 10-year yield is also behaving as though it were already being controlled by the Federal Reserve. Relative both to inflation breakevens and to German bund yields, it has fallen dramatically in the last year. Lower real yields, which offer a lower markup in yields compared to the main European equivalents, should mean a weaker dollar, all else equal:  There are a clutch of other reasons for dollar bearishness (and therefore for optimism about a new regime). George Saravelos, head of foreign exchange strategy for Deutsche Bank AG, lists several. First, as I detailed earlier this week, U.S. economic data has been remarkably positive and surprising in recent weeks, to a far greater extent than the rest of the world. This might well reflect lags in data, and would imply that disappointments lie ahead, which would bring the dollar back lower:  Next, there is the question of flows of funds. Ever so nervously, investors are beginning to buy the argument for Europe, or at least for putting money somewhere other than the U.S. Saravelos illustrates this very simply with flows into U.S.-based ETFs, which suggest sentiment toward Europe is improving:  Using the more ambitious measures of global liquidity kept by CrossBorder Capital of London, we can also see a growing share of liquidity finding its way out of the U.S. As this chart shows, this has been strongly linked with a weakening dollar index in the past:  And finally, there is Covid-19. Europe has earned a reputation for really bad governance over the last decade or so, messing up a series of opportunities to get its house in order. But on Covid-19, the European Union has responded far more effectively than the U.S., and is already close to completing its big economic reopening. Deutsche Bank's real-time mobility data, from Google, suggest that the EU is well ahead of the U.S. in this regard and this should, before too much longer, strengthen the euro against the dollar:  In short, a strong case can be made for a weaker dollar. And that would hasten a new investment regime. It would also probably be good news for Americans. Timing and Bubble Trouble The next "known unknown" and a very serious problem for anyone allocating assets, is the risk of a bubble. Money is fungible. After a period of loose monetary policy, it will find its way to wherever seems to offer the best return, such as tech in the late 1990s and emerging markets in 2007. As I have been detailing of late, there are plenty of signs of a bubble forming in the modern dominant tech stocks, and in anything that is seen as defensive in the era of Covid-19. Regular readers will know that I loathe and detest the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Nasdaq Composite. There is never any good reason to cite either, other than that other people do. Neither index tells you much, and neither is well defined. But, as I receive many complaints that I never cite the Dow or the Nasdaq, I am going to make a change just this once. Thursday saw the Dow fall, while the Nasdaq rose. This has been a pronounced pattern ever since the market began its rebound after the Christmas Eve sell-off of 2018:  Now let us go back to the period from 1998 to 2000, when I was still regularly citing the Dow and the Nasdaq. (I knew no better.) After the Fed panicked and cut rates in the wake of the Long-Term Capital Management meltdown in October 2018, the tech-heavy Nasdaq beat the Dow in an unprecedented way — until the bubble burst. What has happened recently looks quite a lot like the early stages of that famous melt-up:  With the Fed, in particular, determined to keep the monetary spigot open, there is an obvious danger that this will happen again. It is exacerbated by the fact that exciting tech stocks are also perceived to offer a defense against Covid-19, because their business models should not be damaged by it. Someone switching to emerging markets and value stocks now faces the nightmare scenario that the Nasdaq outperforms the Dow by another 100%, as happened 20 years ago, before real life resumes. I'll leave it at that for now. The risks of a bubble are real and have been well-rehearsed, and they create serious problems for anyone allocating money, unless they can truly look only to the very long term. To finish, one intriguing sign that the new regime is indeed on its way: A Clue From the Banks Europe's banking system has been a nightmare ever since the crisis. U.S. banks have had better luck, and have recently enjoyed some good news from lighter regulation. A large part of Europe's problem was the dreadful state of its banks' balance sheets. Wall Streeters widely knew before the crisis that the ultimate buyers of the worst-quality U.S. credit tended to be European banks. But the European negative interest-rate regime, which has made it prohibitively difficult to make profits from normal lending activities, has also been a critical problem. Since the beginning of 2007, when the subprime credit crisis began to take hold, the underperformance of the FTSE Eurofirst 300 euro zone banks index has been atrocious:  But since the worst of the Covid crisis hit us, there has been quite a European banking renaissance. This is the same chart starting at the beginning of this year. In closeup, we can see that Europe's stricken banks have somehow outperformed the biggest American banks by about 30% since late April.  This does not necessarily mean that much. There have been false dawns before. But this looks very much as though American reality, with excruciatingly low rates, is catching up with Europe. Couple that with Europe's greater readiness to resort to fiscal expansion, after years in which German conservatism had ensured that the continent was more austere than the U.S., and it does look as though the conditions for prolonged strengthening of the euro against the dollar are in place. And a weaker dollar would mean an end to the old regime. Survival Tips I gather from my friend and former colleague Gillian Tett that Londoners don't seem to be wearing their face masks. That is a shame, because face masks are turning into a great way to make a fashion statement — or even a political statement. There are plenty of rather scary "I Can't Breathe" or "Black Lives Matter" masks on the New York streets these days, plus any number of sports liveries. It's also plenty possible to make a conservative statement with your mask. Meanwhile, I find British mask fashion rather disappointing. The range of Dominic Cummings face masks is very thin. Much though I love Frida Kahlo, it speaks ill of the British sense of humor that there are more Frida masks around in the U.K. than Dom ones. Get with the plan, Brits, and find a way to enjoy face masks. We're going to be stuck with them for a while yet, and they're really not that uncomfortable. Have some fun with them. And enjoy your weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment