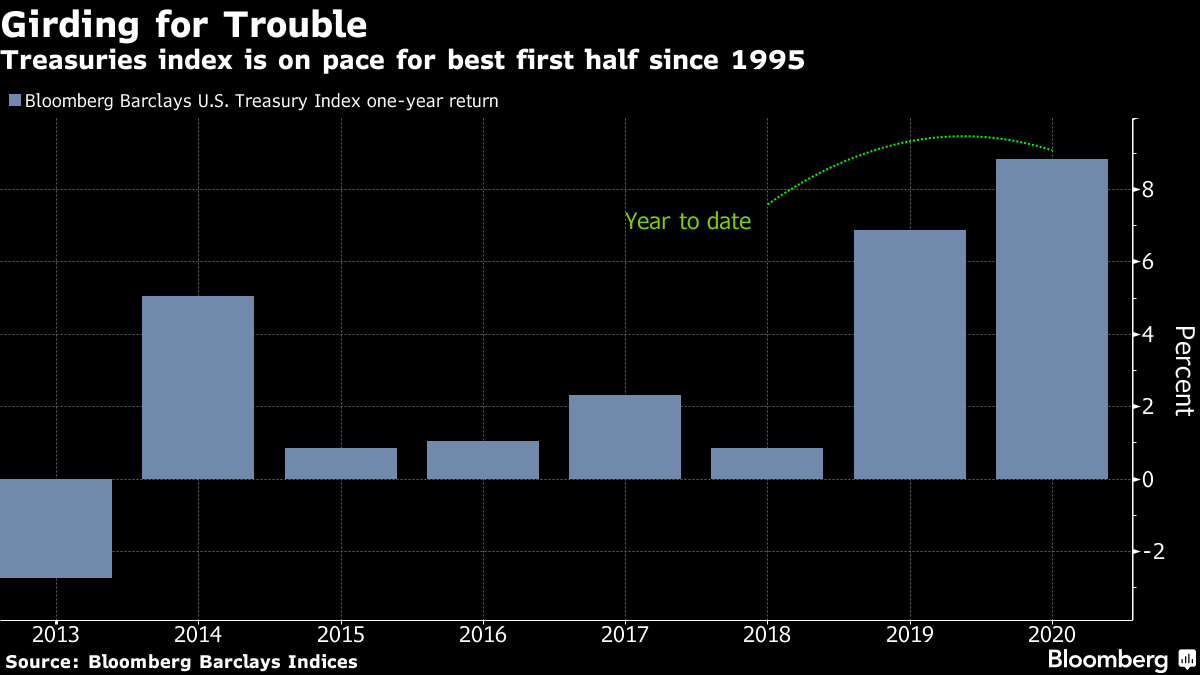

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that would back a moratorium on investment outlooks for the rest of 2020 and possibly beyond. –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter. Lashed by the Curve, Again For every skeptic about the resilience of the U.S. Treasury market in the face of record supply, there's this reality check. Yields have stayed low, while stocks have plotted a swerving upward course through a rocky economic reopening and resurgence of Covid-19 cases. That bond market sang-froid held as the Treasury sold about $94 billion of notes and bonds this week. On Thursday, the Treasury's offer of 30-year bonds sold like hotcakes, triggering a rally that drove long-end yields to their lowest point in two months. And that would have scorched the many fans of the curve steepener trade.  Apparently, you just can't bet against investor appetite for U.S. government bonds -- at least not in the midst of a pandemic. Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic warned Thursday that real-time data suggest the recovery is flattening out, possibly warranting more monetary or fiscal action. The steepener trend seemed well entrenched from March to early June, when the spread between five- and 30-year Treasury yields gapped out to more than 120 basis points. It flourished on the view that near-zero interest rates would pin yields at the front of the curve, while a combination of massive government borrowing and a modest economic recovery would lift the long end. But there were signs the trade was getting overstretched. At the end of June, JPMorgan strategists consulting their active core bond fund manager index saw exposures had reached "levels not seen since the Fed's dovish pivot in early 2019." JPM also indicated that successful bets on a steeper curve were largely responsible for the comeback performance of these funds in the second quarter, which saw their best excess returns in eight years. That didn't stop JPM backing the 5s30s steepener, and it doesn't mean that all bets are off now. BMO Capital Markets' strategists were sticking to their call after the auctions, though with a warning not to expect any impetus from the next crop of inflation data. "Eventually, a steeper curve will reemerge as the path of least resistance, but for the time being we'll respect the price action," BMO's Ian Lyngen wrote. The Next Tantrum The Fed's balance sheet has become one of the greatest preoccupations in financial markets. But as of this week, it looked a tiny bit less stupendous. Assets have dipped below $7 trillion for the first time in almost two months. The $88.3 billion drop in the week to July 8 was the fourth in a row -- taking the total decline over the last month to almost $250 billion. That past month's decline has owed mainly to the declining usage of the Fed's emergency services -- the repo and dollar swap facilities it rolled out for primary dealers and foreign central banks at the height of the market turmoil in March and April. Barring any more dramatic developments, the period to month end could well see a little more shaved off the Fed's ledger, as more than $110 billion of currency swap lines will mature. The major participating central banks, including the Bank of Japan and European Central Bank, have been allowing them to roll off as their local institutions are no longer clamoring for dollars.  This is part of the Fed's success story in stabilizing markets. It headed off a threatened dollar liquidity crunch, and it has effectively weaned dealers off its repo operations, having made them a tad more expensive last month. For the first time since September, the Fed this week could say it had no funds outstanding in these facilities -- a far cry from March, when the central bank offered as much as $5 trillion to put out the fire in funding markets. A drop of a couple of hundred billion and change in the Fed's balance sheet might not look like much here. But it's a bit of perspective for the bond market, which back in 2013 threw the mother of all tantrums when then-Chairman Ben Bernanke dropped a hint about slowing post-GFC asset purchases. The actual balance sheet taper is barely discernible here, extending from October 2017 to mid-2019. The next taper talk -- if it ever comes -- will be a doozy. Green Talks Will the global pandemic stymie our best intentions to fight climate change? As the world's largest and most polluting economies ground to a halt, debates sprung up about whether it might be possible to turn the clock back a little on global warming, or to invest in a cleaner recovery. Europe's leading monetary authority is down with that. "Money talks," European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said this week, in a pretty succinct summary of the case for the central bank to buy more green bonds. The ECB holds quite a few already, whereas the Fed hasn't announced any specific environmental targets for its asset purchases, according to Fitch Ratings. And while the Fed is focusing on improving its aim on a revised inflation-targeting strategy this year, Lagarde proposes a more explicit emphasis on tackling climate change as part of the ECB's strategic review. One option is to plow more of the ECB's upsized 2.8-trillion-euro asset purchase program into green products, and possibly ditch the brown ones. Targeted asset sales could impede market access for less environmentally-friendly issuers, Fitch said, though without a clear taxonomy to identify them, such a policy would be tougher to carry out. Such proposals have raised hackles among the ECB's more conservative ranks, who'd prefer to lump national governments with the controversial task of picking of winners and losers. But Lagarde's pitch, that battling climate change is key to the ECB's mandate to protect financial stability, may yet win the likes of Bundesbank President Jens Weidman over to her "mission critical" stance. And there's more than one way for the ECB to pursue it, with adjustments to its collateral framework, in addition to the existing plans for climate-related stress tests, and adding global warming to its economic models. Lawmakers don't necessarily need much convincing. The EU is aiming for bigger cuts to its greenhouse gas emissions by the end of the decade, and to be net-zero by 2050. The Commission's proposed 750-billion-euro aid package has green strings attached. And European governments are falling in line. Poland blazed the trail in 2016, France has the largest market in the world, and though Spain's inaugural issue is held up by budget delays, Germany plans its first in September and another in the fourth quarter. Meanwhile, flows into ESG ETFs in Europe are rising.  And green bonds are looking more compelling to issuers in the developing world, as ESG investing seems to be gaining traction in emerging markets, with help from strengthening performance and a touch of activism. Chile notched up some savings on euro- and dollar-denominated issues early this year, and other Latam countries looked set to follow before the pandemic crisis struck. There's certainly room for growth, as just $11 billion of the $84 billion raised from ESG-focused bonds this year came from EM issuers. Meanwhile, one of the biggest champions of sustainable investing, BlackRock, is delving deeper into its commitment to take on climate change with a battalion of ETFs. Last month, it launched four new products tracking companies using ESG criteria. The pandemic, far from impeding progress on cleaner investment, has catalyzed it, panelists said on a call describing their outlook for the second half of the year. More Roundtable Chatter... Betting against high-quality government bonds must be relatively high in the ranks of widow-making trades these days. It's easy to overlook that backing them has been pretty lucrative. Treasuries are up close to 9% in the first half of this year, their best first half-performance in since 1995, going by the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Treasury index.  That said -- what do to? With yields this low -- the 10-year Treasury benchmark is yielding about 0.6%, and nearly $14 trillion of debt globally is sub-zero -- it's hard to stay bullish in major government bond markets. Some asset managers are no longer confident in sovereign debt's capacity to fulfill the traditional role of ballast for portfolios against losses on riskier holdings. "Close policy coordination will likely keep bond yields relatively low and that means on one hand that government bonds have less room to rally if things go wobbly, and they offer you less of a cushion in risk-off situations," said BlackRock's Elga Bartsch in the investment giant's roundtable last week. They've trimmed allocations to sovereign debt in strategic portfolios, in favor of inflation-linked bonds. In their second-half outlook, PIMCO portfolio managers Erin Browne and Geraldine Sundstrom were also advocating a few more tools in the diversification kit. They recommended the Japanese yen and Swiss franc, and high-quality assets getting policy support, such as agency mortgage-backed securities and higher-rated investment-grade corporate bonds. That said, they saw the negative correlation between stocks and bonds holding, as history dictates: "U.S. Treasuries have provided a positive nominal return in every single U.S. recession over the past five decades." Movers and Shakers Aviva Plc's new Chief Executive Officer Amanda Blanc plans a rapid review of the business

Solita Marcelli replaced Michael Ryan as UBS AG chief investment officer

Gareth Hughes is appointed head of fixed income and currencies for the Americas at Societe Generale

Mizuho taps NY Fed's Ronald Taylor as head of diversity and inclusion

Wells Fargo hired Kristy Fercho from Flagstar Bancorp Inc. to lead its home-loan business BNY Mellon named Hanneke Smits as CEO of BNY Mellon Investment Management Credit Firms Race to Hire Distress Experts Ahead of More Turmoil Royal Bank of Canada aims for 30% minority executives, sets targets for new hires Bonus Points Why the world is getting angrier, and what that says about the economy If you miss travel, don't read this. But read it anyway. The Fed is digging into how inequality is playing out in the credit market |

Post a Comment