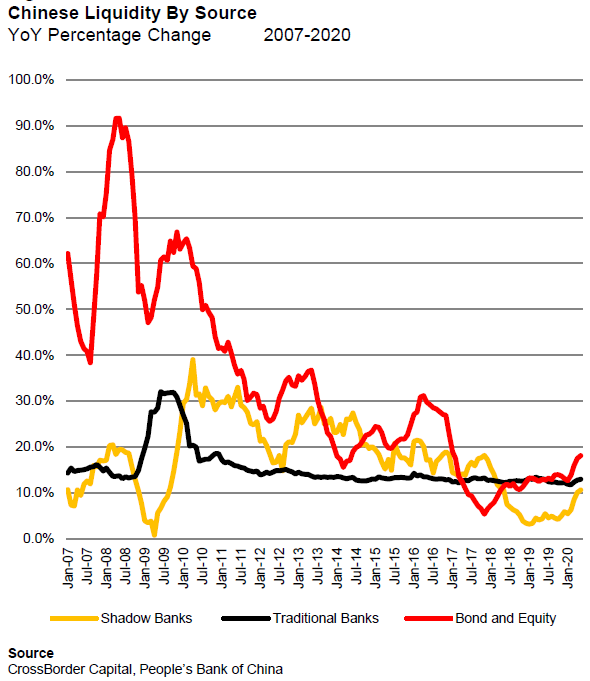

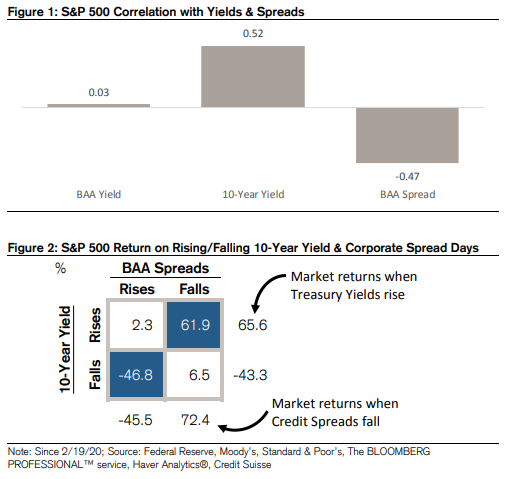

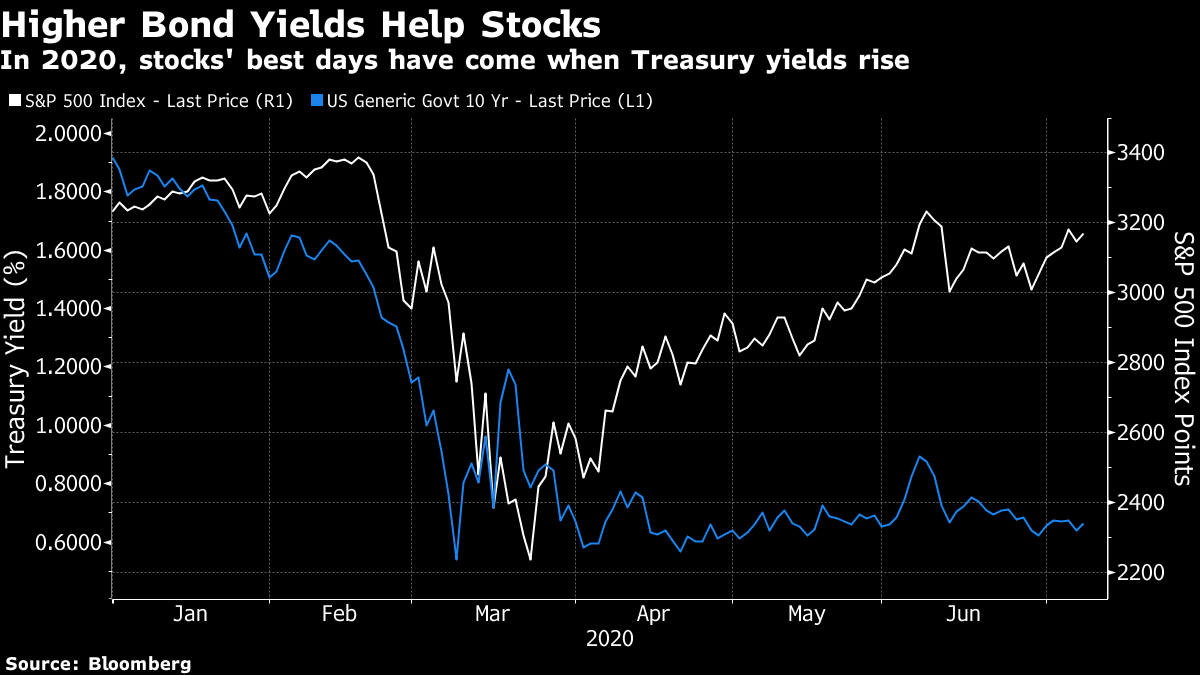

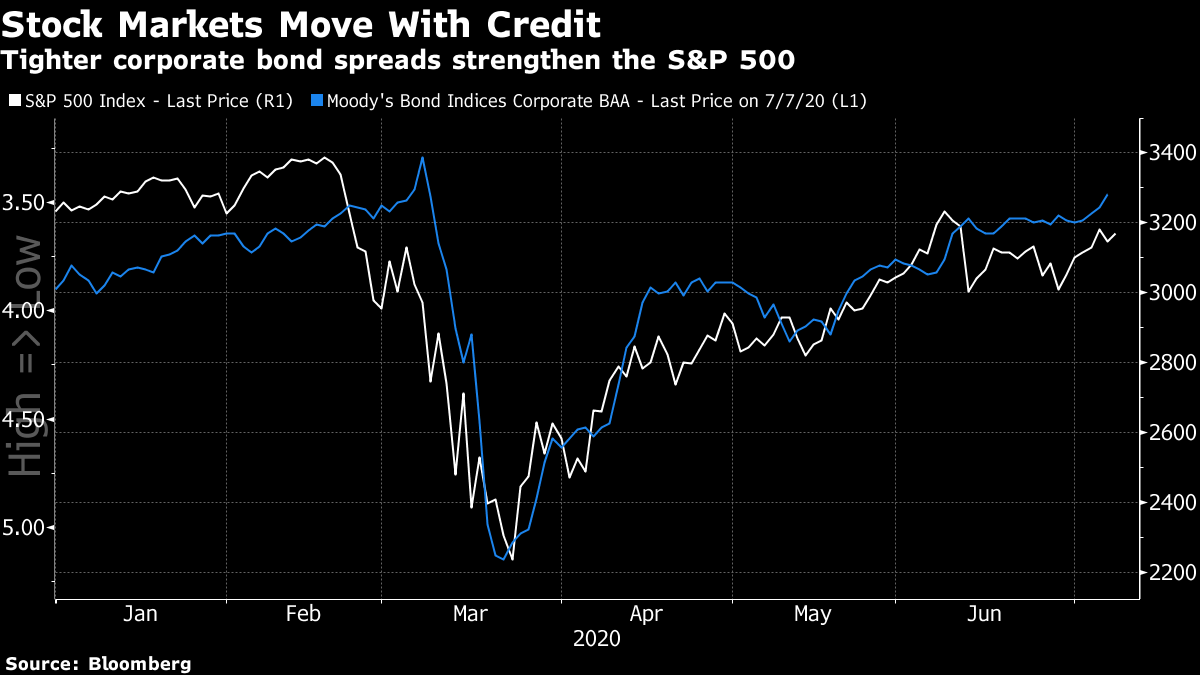

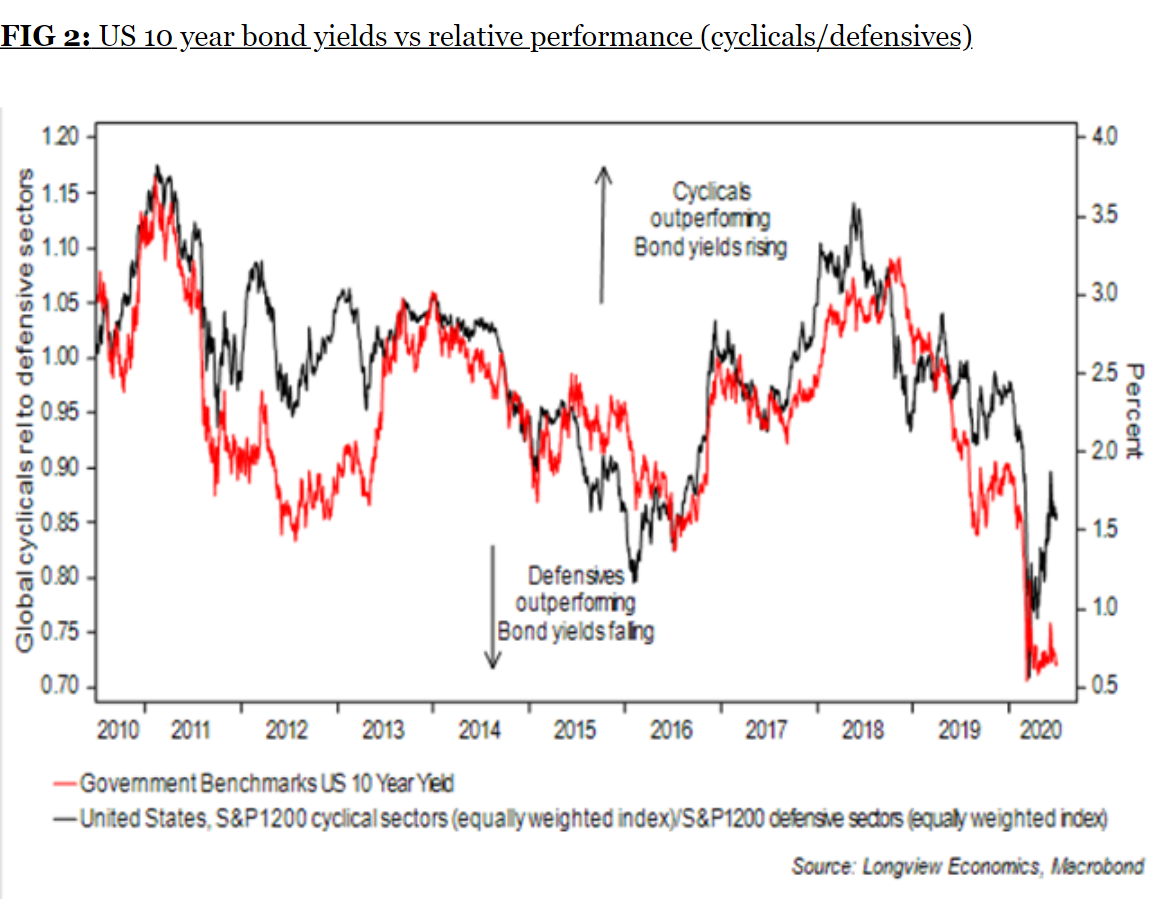

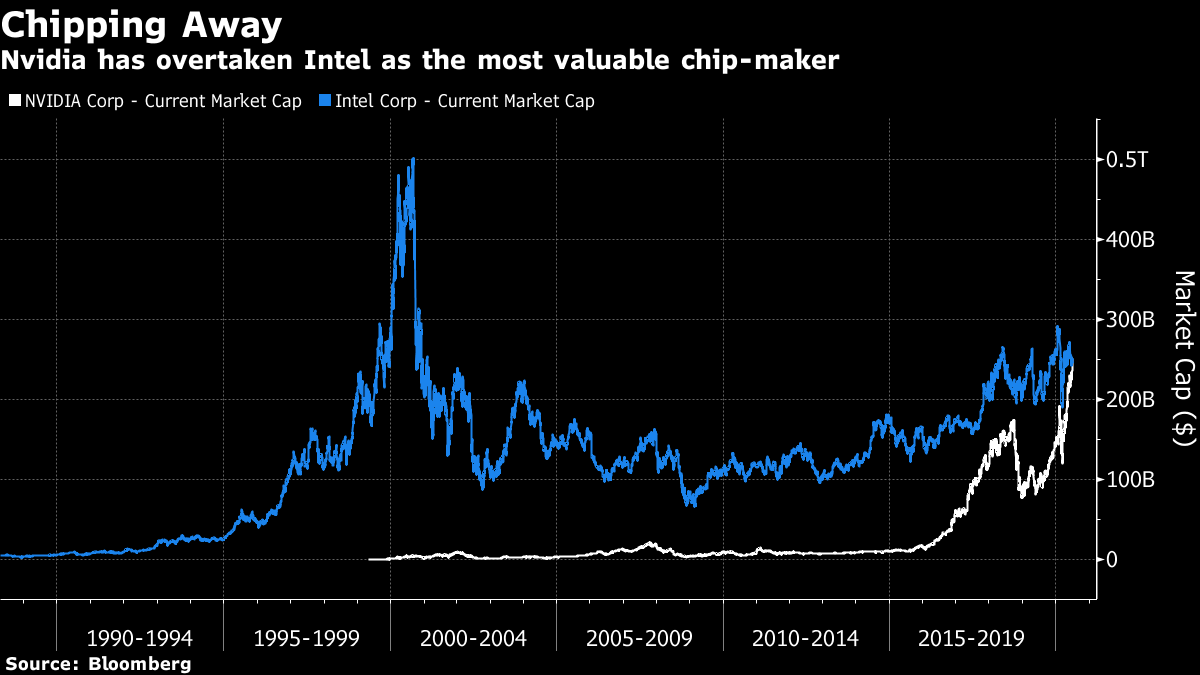

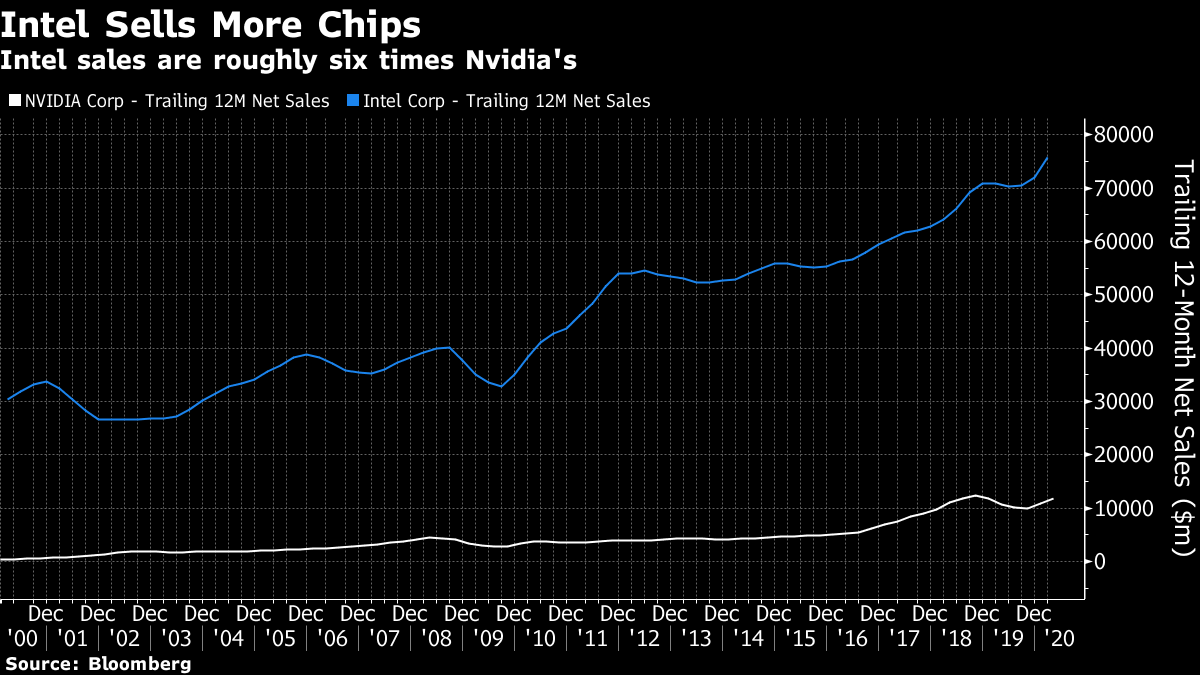

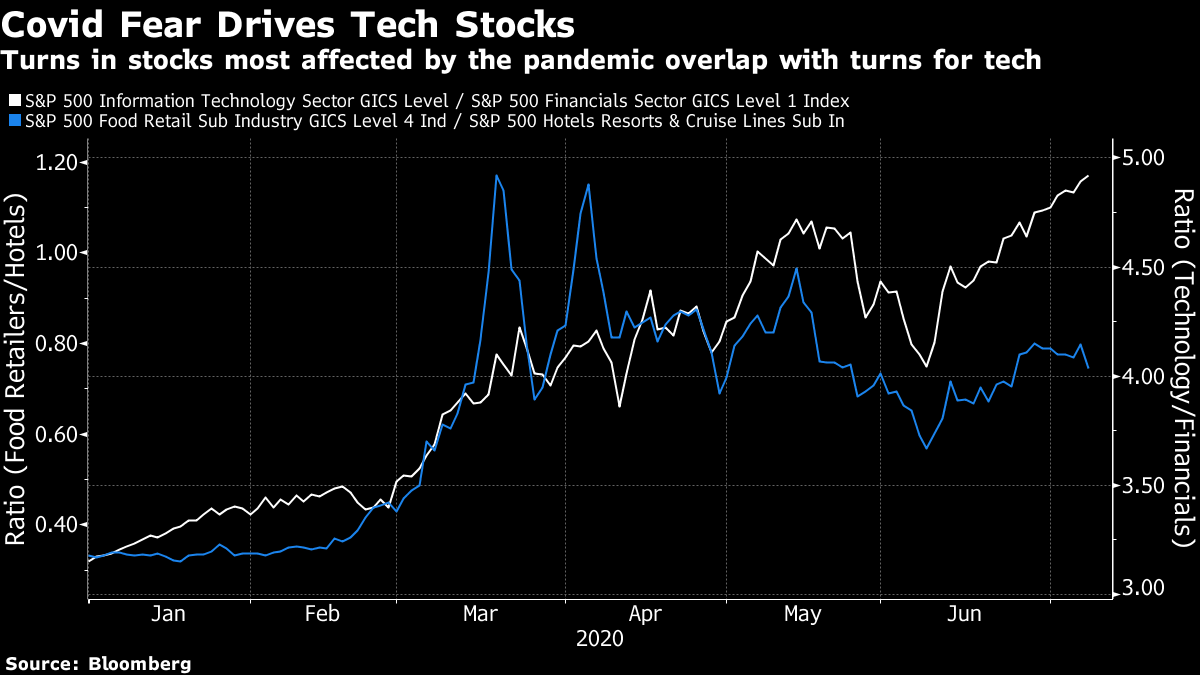

China Shakes the World China, its troublesome credit system and its shaky relationship with the West dominated global markets for years. Then it gave the world the coronavirus. And now, somehow it has slipped from attention, dropping down investors' lists of concerns. This is strange because something important is afoot. Chinese stock markets have far outperformed the rest of emerging markets this year, almost closing a gap that has persisted for decades. China has hosted economic growth, but its equity markets have not logged the returns seen elsewhere — until now:  The last week has seen the domestic Chinese stock market's strongest five-day performance in more than five years, and one of the strongest on record:  China has also, contrary to all expectations earlier this year, seen a noticeable appreciation in the currency, a hot spot in the country's relationship with the West. Last August, Chinese authorities allowed the yuan to weaken and exceed the level of 7 to the dollar, in what appeared to be a retaliation for U.S. threats of added tariffs. Then earlier this year, after a trade ceasefire of sorts had been negotiated, it again broke above 7, this time because of concerns about the damage that the coronavirus would wreak. Now, in a development that suggests a degree of strength in China, and also may remove some heat from its trans-Pacific relationship with the U.S., the yuan has almost returned to the 7 level:  While currency valuations are important, the most significant market "tell" of Chinese economic strength comes from industrial metals prices. At the margin, China has been setting prices for industrial metals for years as it has gone through its growth spurt. And so the 20% rally in Bloomberg's industrial metals index (combined with a gain of more than 30% for iron ore on China's Dalian exchange since April) suggest that China is getting its act together again:  This is a remarkable turnaround, only six months from the beginning of the pandemic. How has it been achieved? The best guess is that China has pressed the pedal on expanding credit once more, but not by using orthodox monetary policy and not in a way that weakens the currency. The following chart, from CrossBorder Capital LLC of London tells the story of the remarkable expansion of Chinese credit over the last quarter of a century as well as anything:  The stimulus applied by Shanghai's big equity bubble in 2007, and then by the huge extra spending and credit easing that started in late 2008 to deal with the last global financial crisis, was on a different scale from the stimulus that is now being applied. Much of that was achieved via shadow banks, shown by the yellow line, whose opaque structures led to concerns that China could stage its own repeat of the Lehman crisis. The People's Bank of China has spent the last few years in an explicit attempt to avert this risk, and now appears to have shadow banking under control. That has allowed them to unleash a 20% increase in liquidity, through traditional banks and through the bond and equity markets. For the short term, this can only be positive. Questions will rightly continue about whether the Chinese regime, attempting to use a communist command structure to regulate a capitalist economy, can possibly endure. It is only a few months since the Communist Party's inadequate response to the early stages of the pandemic appeared to be heralding major change. But for the short term, China appears to have been able to right its ship, and to find the money to keep its economy nicely afloat. This could be a vital precondition for a cyclical upturn in the emerging markets. They also need to contain the economic damage done by the pandemic, and this is far from certain in major countries such as India and Brazil. And they would be greatly helped by a further weakening of the dollar. Emerging currencies have picked up a little in the last month, but would be helped by much more dollar weakness. If these preconditions can be met, however, the world is beginning to show the symptoms of previous periods when China was in the ascendant. Along with strong industrial metals, we also have a gold price that is as high as it was the last time that China was stimulating with full force at the beginning of the last decade. Nobody knows how long it can last, but it looks like the Chinese economic machine might be able to drive one more economic cycle. Credit Where It's Due Are markets moving on the back of ultra-low interest rates from the Federal Reserve, which justify more expensive stock valuations, or on greater optimism about economic growth? The two will often tend to go together, but a neat piece of research by Credit Suisse AG's U.S. equity strategist Jonathan Golub on the links between stocks' performance and the corporate credit and Treasury markets suggests that the greater driver at present is economic optimism. As the following chart shows, the S&P 500 Index has been strongly correlated with the 10-year yield since it peaked pre-Covid on Feb. 19, but not in the way we would expect if the market were reliant on cheap money. Instead, there is a positive correlation between Treasury yields and stocks, meaning stocks go up when money gets more expensive. There is also a negative correlation between investment-grade corporate bonds' spread over Treasuries and stocks. But there is no correlation to speak of between the actual yield at which companies can borrow and their share price. The following chart illustrates the relationship:  Alternatively, we can look at how these relationships have moved over time. This shows the 10-year yield against the S&P 500 for the year so far. The 10-year yield has been comatose for months, but note that stocks' best days have come when Treasury yields are rising:  When we look at corporate spreads, on an inverted scale, against the S&P 500, we can again see a clear relationship. Tighter yields mean higher share prices:  The common thread here is that tighter spreads and higher Treasury yields both imply confidence about the economy. So we can perhaps infer, as Golub puts it, that the market "seems far more focused on economic health than a declining cost of capital." That is encouraging — although it also perhaps means that cheap money is now taken for granted, and the market has become extra-sensitive to any signs of economic growth or the lack of it. For a further indicator that the market has been most interested in economic growth since the Fed assured rock-bottom 10-year yields, look at this chart of the relative performance of defensive and cyclical sectors, from Longview Economics in London. Normally this moves very much in line with bond yields. There is a still correlation (in that they tend to move in the same direction), but cyclicals have enjoyed more of a recovery than would have been implied by bond yields alone:  For the time being, the Fed is not moving the market on a day-to-day basis; investors are instead focused more on the chances for growth. That means ever greater concern about the balance of risks around the pandemic, and it also means looking at efforts to reinvigorate fiscal policy. Monetary policy has gone as far as it can and is now more or less taken as given. When the Chips Are Down ... A small corporate landmark: On Wednesday, Nvidia Inc.'s market value overtook that of Intel Corp. to become the biggest U.S> chipmaker by market capitalization. This was quite a feat. One of the great companies that drove the rise of personal computing and the internet, Intel was worth almost $500 billion more than Nvidia at one point in 2000, when the tech bubble was near its peak, and Nvidia had recently gone public. Now, at last, the lines have crossed:  There are some good reasons for this. Nvidia specializes in graphic chips that are beloved of gamers, an industry that is booming even more during the pandemic. It is also a big player in data centers, and in bitcoin mining, giving its stock an extra edge. A higher multiple for Nvidia than for Intel does therefore seem justified. But on a price-to-sales basis, Nvidia is now twice as expensive as Intel was at the top of the bubble in 2000:  Meanwhile, Intel continues to generate more sales than Nvidia, and the gap is even widening:  Why such total excitement about Nvidia, then? Its attachment to various glossy and exciting trends is important. So is the fact that it is included in the NYSE Fang+ Index, which has created intense excitement. And then there is the strange fact that expensive technology companies are associated in investors' minds with security, and with Covid-proofness. The relative performance of information technology to banks (which are obviously sensitive to slowdowns in economic activity) overlaps surprisingly closely with a pure "Covid Fear" index, featured Wednesday, of food retailers relative to hotels.  Somehow, in a weird world dominated by algorithms, passive investing vehicles, and an exceptionally lenient Fed, security has become a reason to bid up the price of Nvidia to the skies. As with companies such as Cisco that enjoyed even headier valuations 20 years ago before they crashed, Nvidia is a perfectly good company. But such valuations look alarming. Survival Tips Before you go into the water, make sure there are no sharks. And if you believe there are sharks in the water, don't let anyone go in. "Jaws," the first great summer blockbuster, has its 45th anniversary this year. (Spoiler alert for the few who haven't seen it: A great white shark eats a lot of people before it gets blown up in the final scene.) It is a great film, still terrifying on the 10th viewing, and well worth watching if you've never seen it. But what lessons does it have for us today, other than not to get into the water if sharks are around (as they are presently at Cape Cod)? Much of the human drama concerns the mayor of the small tourist town, who insists on keeping the beaches open for the sake of business. A child's life is lost as a result. According to Jennifer Weiner, writing in the New York Times, the real horror of the movie is the mayor, and not the shark. She draws some strong parallels with the attitude that President Trump has taken to Covid-19. According to the U.K.'s prime minister, Boris Johnson, speaking when he was mayor of London, the mayor is in fact the film's hero. Make of this what you will. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment