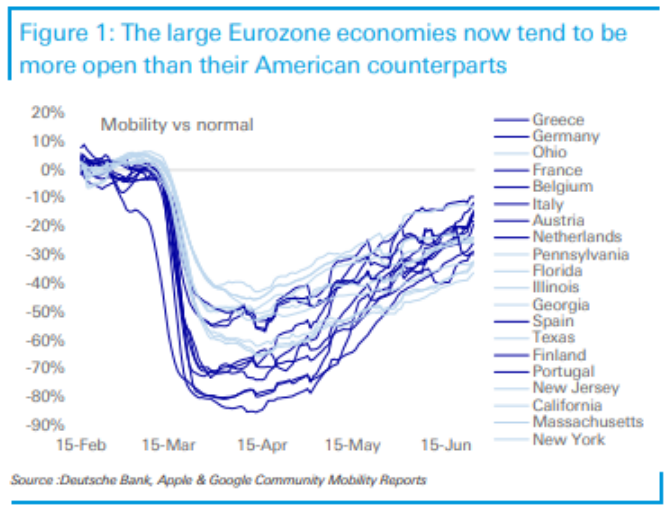

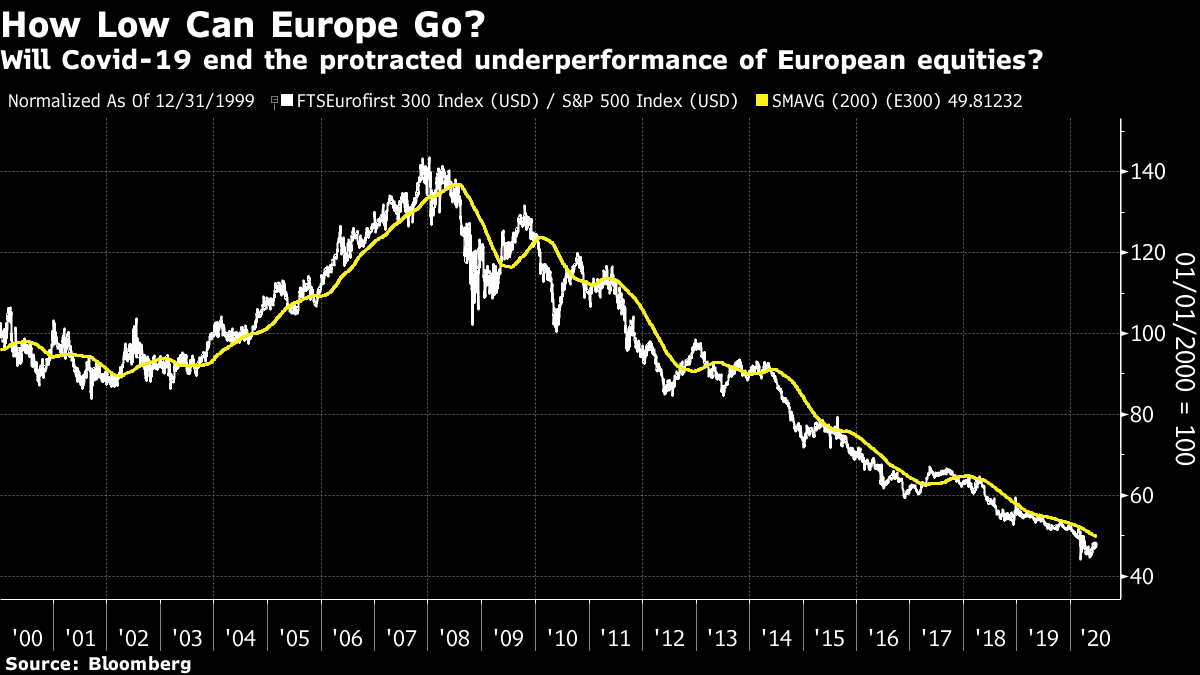

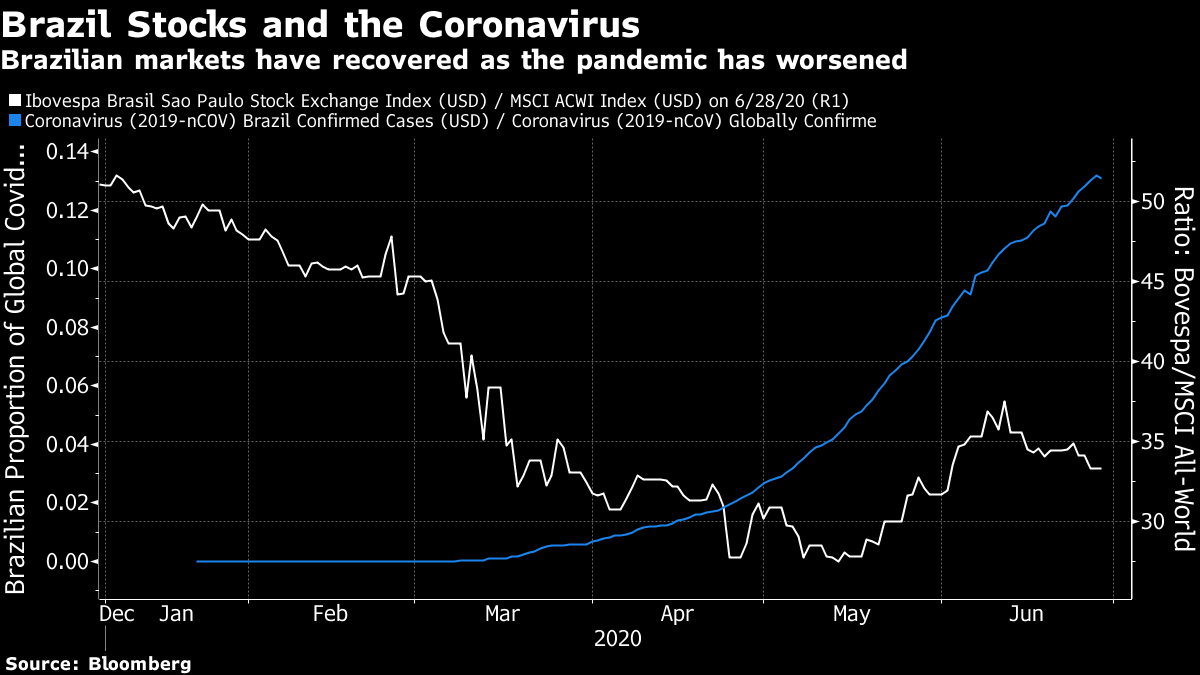

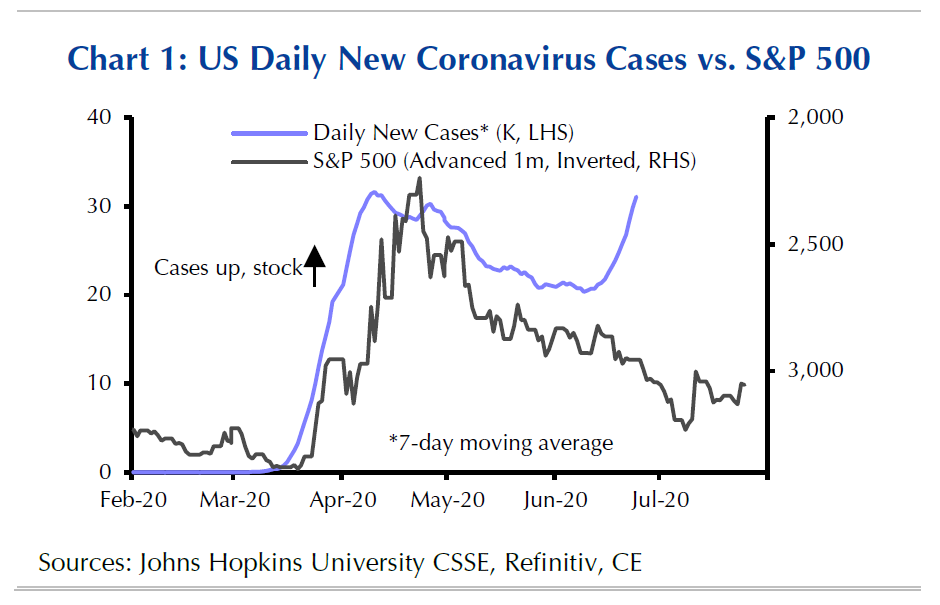

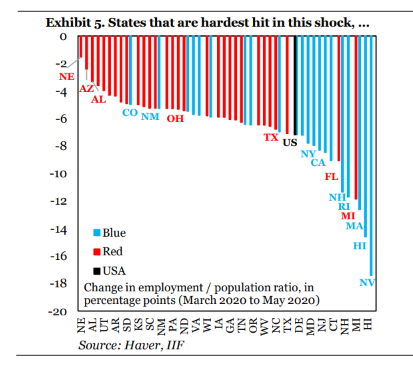

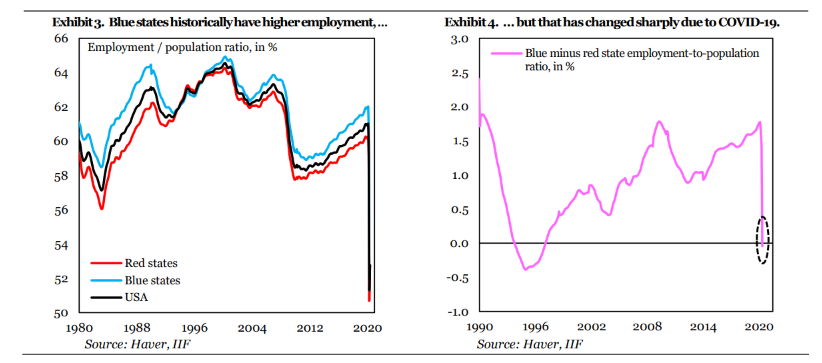

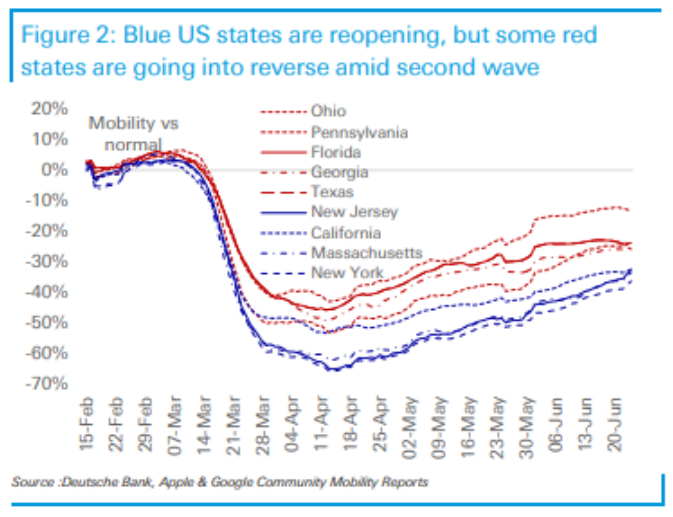

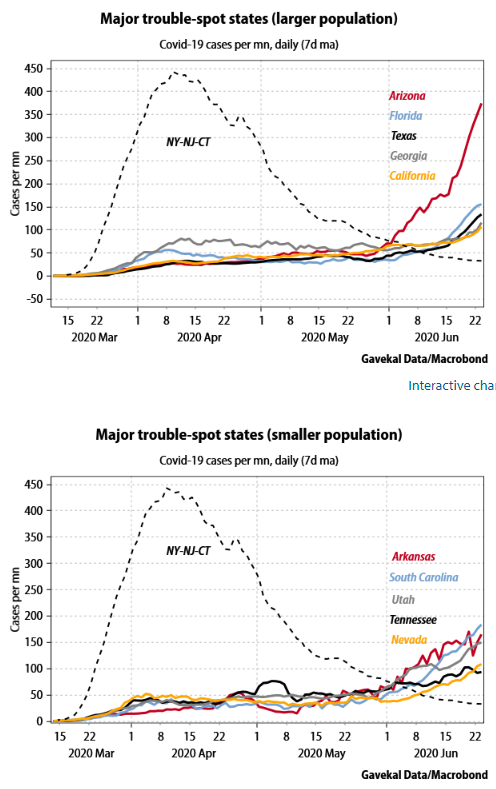

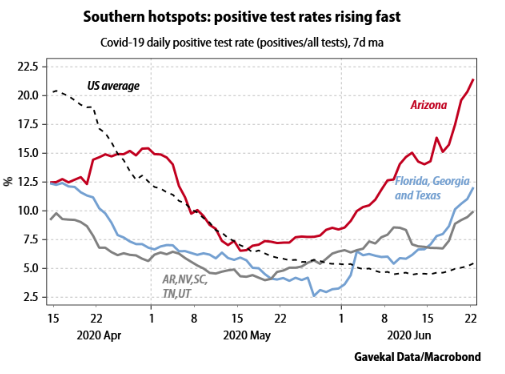

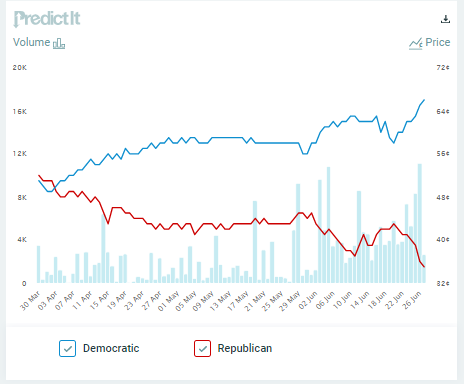

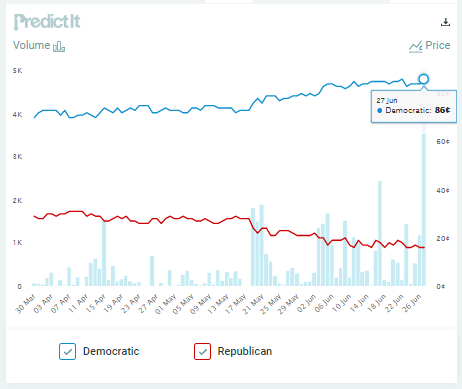

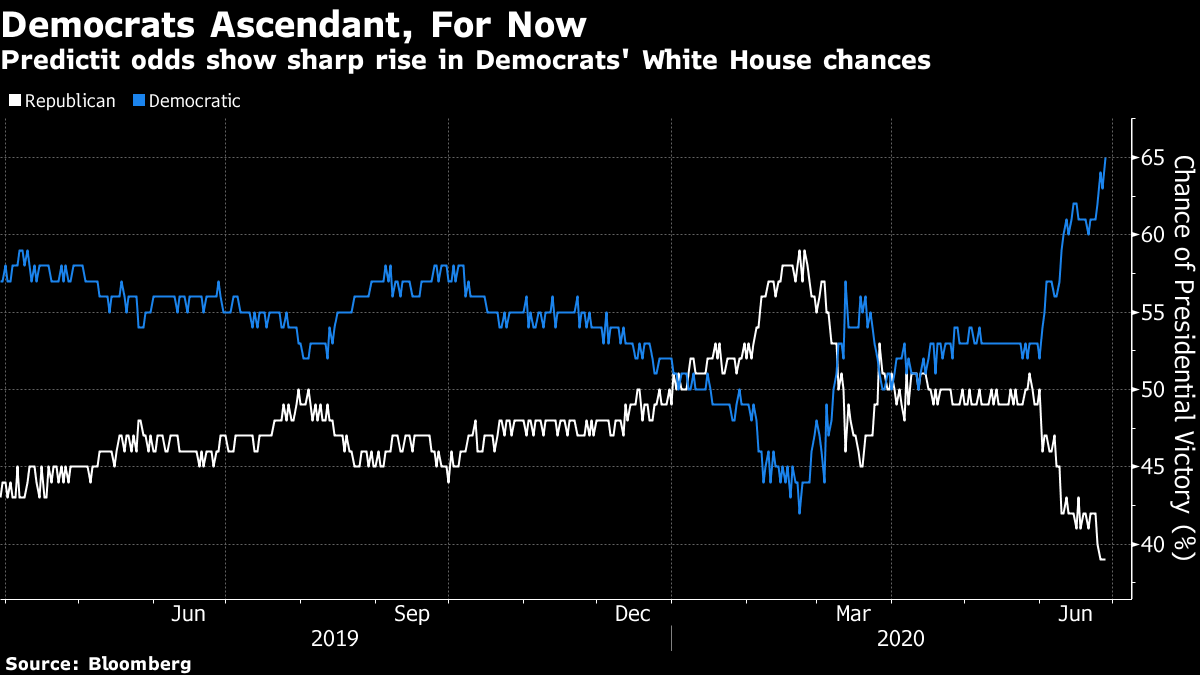

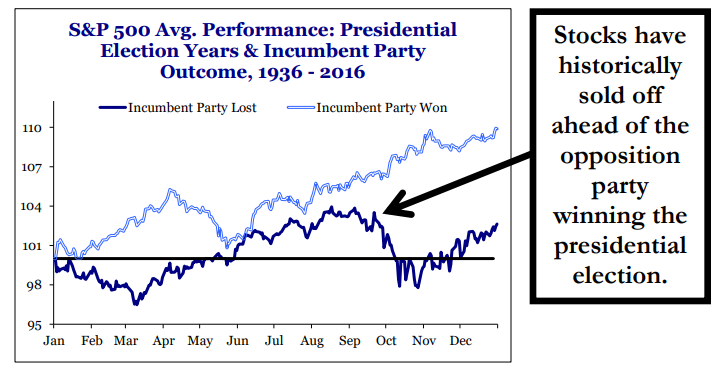

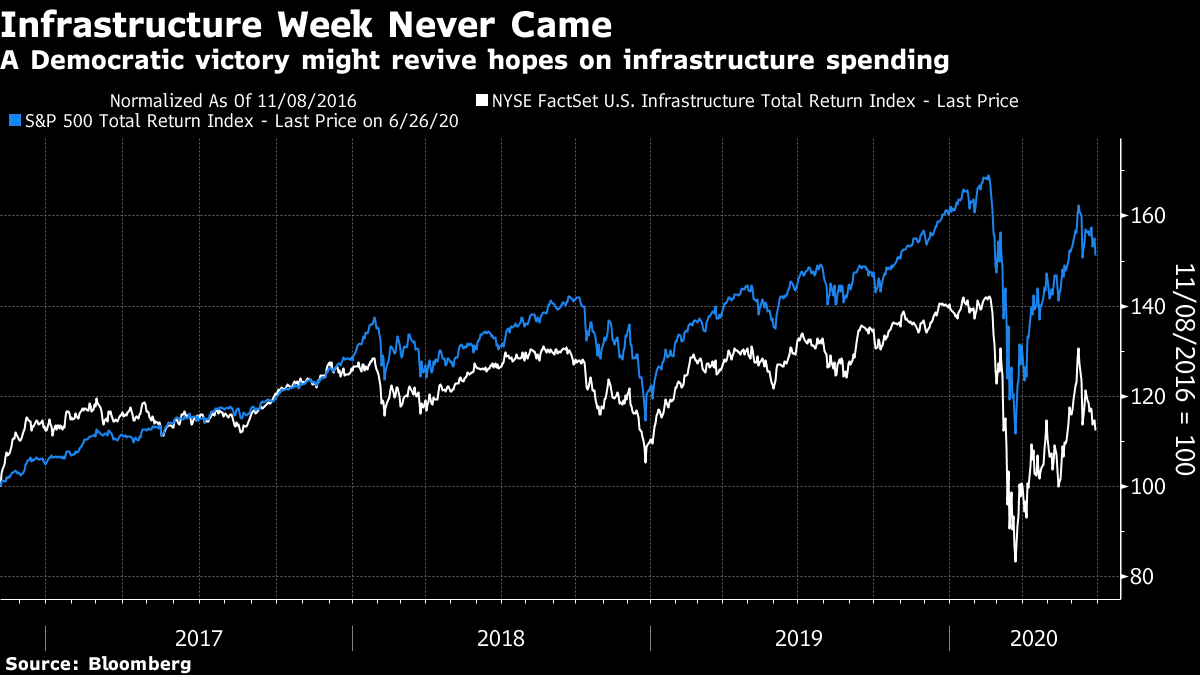

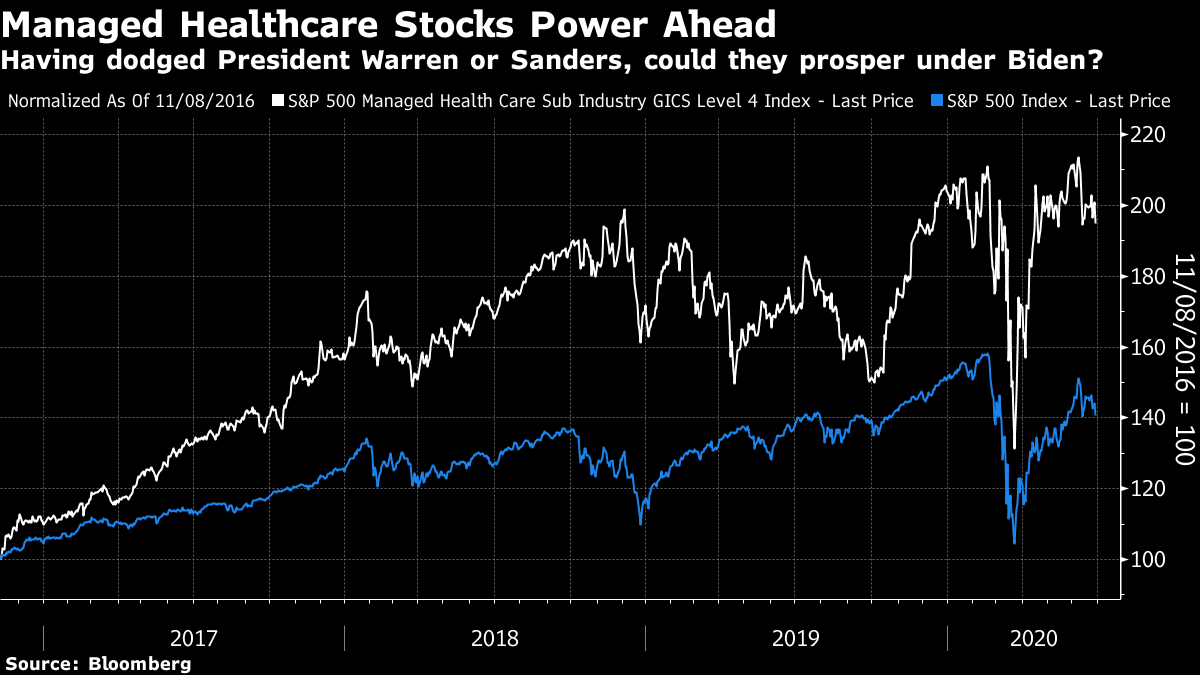

Midsommar The year is still not half over. The history of Covid-19, and how it should best be combated, will not be written for a long while yet. So far, 2020 has already seen prognostications that the pandemic could mean the end of Xi Jinping and the communist regime in China, and that socialized or nationalized health care had been shown to fail definitively during the disaster that afflicted northern Italy in the late winter. I say all this as a preface to what will unavoidably be yet another newsletter devoted almost entirely to the coronavirus. At this point in the pandemic's progress, it is the U.S. and its economic and political model that appears to have failed. Has it? And what will be the economic and financial consequences? Let's start with a killing graph which my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Mark Gongloff describes as "the new visual signifier of American hubris and premature end-zone dancing, replacing the Mission Accomplished banner": Back in March, President Donald Trump made a big deal of blocking entry to the U.S. by people of the European Union, on the basis of the bloc's poor record in dealing with the coronavirus. The ban remains in effect. From next month, in what must occasion great schadenfreude in the capitals of Europe, it will probably be the other way around. Meanwhile, the effect of the American failure to stop the virus is beginning to be felt in real-time economic activity. This chart was produced by Deutsche Bank AG with the aid of mobility data collected by Apple and Google. Europeans' mobility now tends to be much closer to normal than Americans':  Could that yet have an impact on markets? It is certainly possible. U.S. stock markets have far outperformed their counterparts in the EU for more than a decade. Given the U.S. success in producing the companies that now provide the dominant platforms for the internet, and its ability to bolster its banking system far more effectively than the EU could do, this should not be surprising. For the last few years, any brief incursion in the FTSE-Eurofirst 300's relative performance to the S&P 500 above its 200-day moving average has been met with a renewed dose of weakness for European stocks:  To be clear, there is no direct link between the pandemic and the performance of stock markets, in either relative or absolute terms. There are too many other variables in play (starting with the money being deployed by central banks). For one very strange example of how global risk aversion and liquidity swamped any specific issues of the coronavirus, look at how Brazil's stock market tanked relative to the rest of the world when it still accounted for a negligible proportion of global Covid cases, and then recovered even as Brazil started to become one of the most serious global hot spots, accounting now for almost 14% of global confirmed cases:  But there are signs that anxiety about the spread of the virus through the American Sun Belt is putting U.S. equities under pressure again. If we look at how airlines, hotels and cruises — the sectors most obviously affected by the virus — have performed relative to the rest of the market, we can see concern that reopening was not going according to plan start to set in after an initial peak of enthusiasm three weeks ago:  There has also been an anxious reluctance for the market as a whole to respond to the obvious pickup in cases. There are justifications for this, as the rise in cases is partly due to wider testing, and the death rate is significantly lower than it was. But as the following chart produced by Capital Economics Ltd. shows, the way the U.S. stock market has looked through rising Covid-19 cases in the U.S. over the last month has been very strange:  As it stands, the latest fall for the S&P 500 on Friday brought it just below its 200-day moving average, which also happens to be almost exactly at the level of 3,000. The last time the market faced this dual landmark, stocks went higher again. After a weekend of unremittingly negative and scary headlines from across the Sun Belt, it will be very interesting to see if this can happen again.  Whatever happens in absolute terms, it is hard to see how the U.S. market can keep performing so much better than its European counterpart, when Europe has shown that the ability to do what the U.S. cannot, and bring the virus under control. Covid-19 and Politics How exactly will this affect the U.S. election, which is now only a little more than four months off? At first, as this chart from the Institute of International Finance shows, the worst affected states economically were politically blue:  The IIF shows that this was even enough to level a historic imbalance between red and blue states. Employment tended to be higher in blue states, until the virus hit:  But that is changing. Whether or not this is due to political decisions, the economic effects are clear. As this Deutsche Bank chart shows, red states had a significantly quicker return to mobility, but are now reversing course:  Gavekal Economics provides a handy summary of just how ugly the situation now looks in a range of the bigger Sun Belt states, while things look even more grim in some of the smaller Southern states, where the African-American population appears to be disproportionately affected:  Also, to be crystal clear, this cannot possibly be ascribed merely to more testing. Indeed, in Arizona the percentage of positive tests is terrifying and suggests a much more serious outbreak is on its way:  It is no longer possible to doubt that we have a worrying problem on our hands. As the death rate is reducing, and many of the cases now being reported are among younger people less likely to be severely affected, the good news is that it is still possible to avoid a full repeat of the scenes seen earlier in Wuhan, Milan and New York City. However, the failure of policy and leadership in Arizona, a once reliably red state that produced Republican presidential candidates Barry Goldwater and John McCain, appears total. This is how the Predictit.org prediction market currently gauges the odds for the presidential election in November:  Meanwhile Arizona also has a Senate election this year, where the Republican Senator Martha McSally will be defending her seat. Predictit bettors seem to think that she is as good as defeated already:  The Predictit market's wagering on the presidency is more guarded, but the chances of a Democratic victory are now put at almost two in three, the strongest they have been. Given the amount of change in the last four months, it is plenty possible that there will be as much change in the next four months. For the time being, the president is in a political hole:  What effect should this have on the markets? It will be negative. Before you write in to tell me that stocks historically have performed better under Democratic presidents, which is true as far as it goes, please take a look at the following chart, from Strategas Research Partners, which shows the performance of the S&P in election years when the incumbent party wins, compared to when it eventually loses:  Stocks are currently doing somewhat worse than they normally do in a year when the incumbent goes down to defeat. Causation works in both directions: A poorly performing stock market suggests that the president will have a harder time selling his party to the electorate, while political problems for the incumbent mean extra uncertainty, which markets dislike. At present, with the S&P 500 threatening to drop below 3,000 and its 200-day moving average again, the short-term political risks appear to be to the downside. What might work? China-exposed companies The companies most exposed to China have had a bumpy ride over the last few years, as the Chinese currency crisis of 2015 and then the trade conflict with the U.S. have buffeted values. At present, MSCI's index of the 100 companies in the MSCI World index with the greatest exposure to China is performing better relative to the rest of the world than at almost any time since 2015:  This reflects the perceived Chinese success in dealing with the virus. Politics add more spice to this. It would obviously be good politics for President Trump to amp up anti-Chinese rhetoric over the next few months — but this would risk further damage to the stock market. Should Joe Biden (or "Beijing Biden" as the Trump campaigns wants us to call him) be victorious, then the chances are that China's relationship with the U.S. becomes a little easier. Either way, those with a stomach for volatility might want to try buying stocks heavily exposed to China. Infrastructure stocks After high initial hopes, it became a running joke in Washington that the Trump administration's "infrastructure week" never came to anything. If a new Democratic administration found itself with any fiscal space to do anything, it would presumably look to put money into infrastructure, for which the need is undeniable. Infrastructure stocks have been lagging the market badly since it became clear that no big splurge on such projects would happen under Trump:  Low-taxed companies Any stock with a high effective tax rate becomes a likely victim of a Biden presidency, as Democrats would be almost certain to reverse at least part of the controversial cut in corporate taxes made by Trump at the end of 2017. In practice, the tax cut benefit was most useful for utilities, which had few loopholes for avoiding tax; so they would not react well to a Biden victory. Health-care companies Health care will be at the top of the Democratic agenda. The question is exactly what they would choose to do. "Medicare for All" would be disastrous for health insurers, as it would effectively put them out of business. An expansion of Obamacare might do them a lot of good. In a highly contrarian call, Strategas suggests that this is what lies ahead, and that health-care stocks are therefore a counter-intuitive buy in the event of a Biden victory. That might help to explain why managed health-care companies' stocks are managing to stay afloat amid a pandemic and deep political uncertainty.  Survival Tips Statues, of all things, are turning into a major issue — and one that the president evidently hopes could turn around his prospects. Naming rights also seem to matter, and amid many other developments, the weekend brought the news that Princeton University would take the name of Woodrow Wilson off its school of public affairs, and a residential college. Beyond being a two-term president of the U.S., he had also been a successful president of Princeton itself, so this was a dramatic gesture. But at least the episode has taught us that Wilson was not merely an internationalist dreamer, but also a hard-core racist. If Americans are finding the cognitive dissonance difficult to process, you might take comfort from the fact that Britain is turning itself inside out over Winston Churchill. The British policy on statues has generally been laissez faire — so much so that the statue of Charles I in Westminster is not far from the statue of Oliver Cromwell, who had him beheaded. Churchill's name is now synonymous with the decision not to sue for peace with Hitler, which is what most people feel his statues commemorate. More or less everything else in his career was a disaster. For a fascinating discussion between an Englishman, an Irishman and an Englishwoman on whether Churchill's statue should still be in place in Westminster, I recommend this podcast. Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment