Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter currently fixated on those little differences in global monetary policies. –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter.

PBOC Quandary

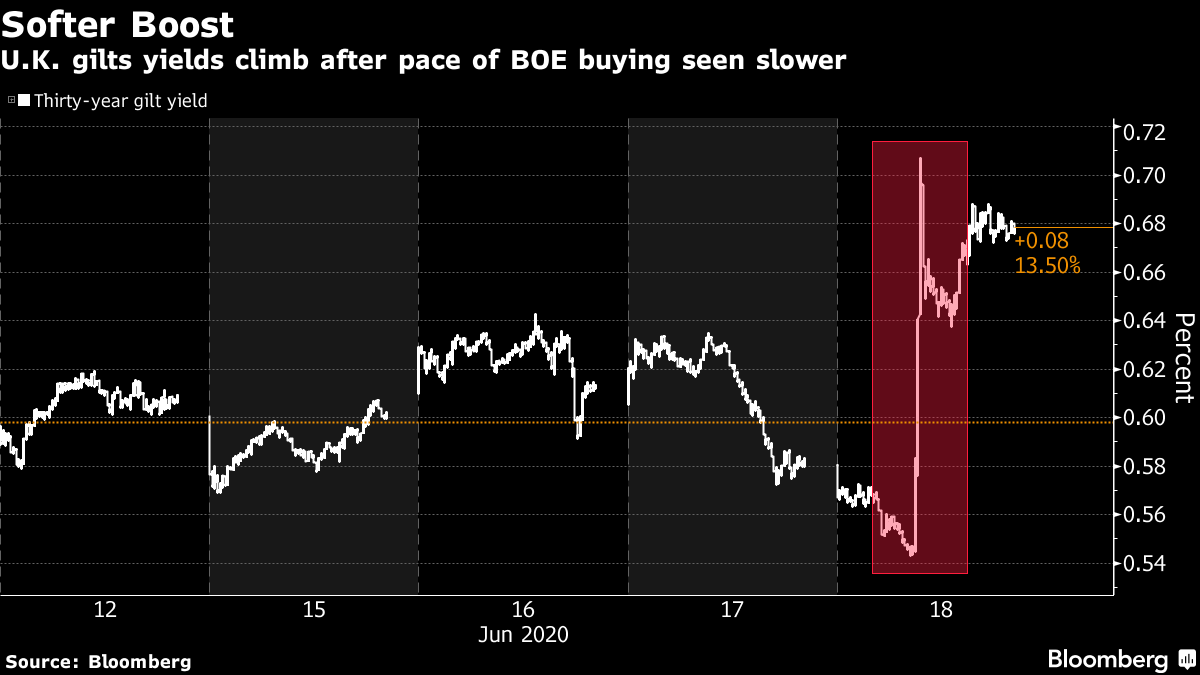

By the time you're reading this, China's central bank might have pulled another lever to loosen policy that many now consider too constrictive given the still-damaged economy. Calls for more action have certainly been getting louder, as Beijing implements localized lockdowns on a second wave of COVID-19, and liquidity concerns mount in the world's second-largest bond market. While U.S. yields appear to have returned to more or less boring ranges, China's rates markets are looking increasingly stressed. The People's Bank of China has taken further steps to ease policy this week, injecting short-term funds into the financial system Thursday and cutting the cost of loans. But repo rates climbed for a third session and benchmark government yields headed to multi-month highs. China's 10-year debt is the world's third-worst performer since May, following Bulgarian and Pakistani local-currency bonds. The pressures are made worse by supply concerns: China plans to issue 1 trillion yuan ($141 billion) of special government debt by the end of July to combat the pandemic. And the country hiked its 2020 budget deficit target to 3.6% of gross domestic product, which, while still relatively low, is up from 2.8% last year. Policy makers have signaled they'll lower the required-reserve ratio (RRR) to free up more cash for banks to lend, and some market watchers think a move is imminent.  The central bank's delay may be a response to concerns about a repeat of the scenario earlier this year. The People's Bank of China pumped trillions of yuan into the financial system, only to find that while those policies did spur lending, arbitrage also flourished as companies plowed cheap funds into high-yielding investment products, diverting money from the real economy. And China's leadership has repeatedly said it won't flood the financial system with liquidity -- an attempt to avoid a repeat of the massive debt surge a decade ago that left a legacy of plenty of bad loans. The latest data showed signs that China's economic indicators might have troughed, but David Qu at Bloomberg Economics says they still suggest a "relatively strong" need for looser monetary policy, even absent the threat of a second wave of the virus. Industrial production is down sharply on the year, and exports fell in May, reversing much of the prior month's increase amid lockdowns in China's trading partners. Moreover, consumption is lagging behind the rest of the economy. Qu expects the PBOC will ease further -- albeit slowly -- with actions including targeted cuts to RRR and the one-year loan prime rate. Delicate ElephantsThe Federal Reserve chair has a way with words. At least, he was colorful in his imagery when asked this week about the risks of its unprecedented step to buy corporate bonds. "I don't see us wanting to run through the bond market like an elephant snuffing out price signals," Chair Jerome Powell said in a semiannual hearing at Congress. For fans of Dr. Seuss, this statement might call to mind the elephant-hero Horton, who was commandeered into incubating an egg. The Fed is similarly perched carefully on the credit-market egg, mindful of its duty, rather than the supremely awkward position it's in. And Horton's motto may also apply here: "An elephant's faithful, one hundred percent." Instead of simply saying it will buy corporate bonds, and letting the market jump to its own conclusions -- as it has, with searing rallies and record issuance in both March and April -- the Fed delivered. While acknowledging that the assistance isn't really needed right now, the Fed's two corporate credit facilities have added another couple billion dollars over the past week. The modest purchases have invited plenty of criticism, ranging from charges by some lawmakers of stoking moral hazard, to billionaire money manager Jeffrey Gundlach's accusations that the facilities violate the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 and have crushed volatility in the high-yield and investment-grade markets. Anyone steeped in Japan's experience would be familiar with Gundlach's line of criticism. The Bank of Japan gobbled up so much of the government bond market over decades of stimulus that the industry warned about permanent damage to the infrastructure. Market participants in recent years told the central bank that the deadened liquidity caused by the BOJ left dealers sometimes unable to execute a larger-sized transaction. And they cautioned that the ranks of experienced traders were thinning out. It's hard to have price discovery if there's nobody left to discover it. The Fed this week took steps to address a very different source of angst, that the scope of its purchases might be limited, or skewed, by its focus on exchange-traded funds (at the top of which sits ETF giant and the facilities' administrator, BlackRock.) The central bank announced Monday that its Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility is shifting away from buying bond ETFs, to follow a diversified market index it built specifically to comprise all eligible securities. The move removes a possible hurdle for companies in registering for access, and gives the Fed more control over its interventions, rather than being "a passive lender of last resort," says Julia Coronado, president and founder of MacroPolicy Perspectives. "By defining an index, the Fed takes control of its purchases. It will buy the market in an indexed, even-handed way, and it will do so when it decides to." It also expands the Fed's potential corporate bond purchases out to an estimated $1.7 trillion universe from the $256 billion world of ETFs, according to Bank of America strategists led by Hans Mikkelsen. Read more on the upshot for ETFs of the Fed's new approach to corporate bond purchases As of now, the facilities have proven their effectiveness as a source of market support -- they've already dug the $860 billion U.S. bond ETF market out of a hole, propelled high-grade corporate bond issuance beyond $1 trillion this year, pulled down borrowing costs and dropped premia on insuring riskier debt.  As for further market gains, BMO Capital Markets strategist Dan Krieter reckons the bulk of the performance boost has probably been mostly wrung out by now "because these facilities are now truly emergency facilities." ECB SpreeMeanwhile, in a world that's still beyond the pale for the Fed, the European Central Bank will pay banks to take 1.31 trillion euros ($1.47 trillion) off its hands. The ECB's latest round of TLTROs (Act III, Scene IV) was the biggest bang yet: 742 banks tapped the loans, which carry a rate of minus 1%, provided the borrowers hit specific targets for lending to companies and households. The operation added a net 549 billion euros to the financial system, and Societe Generale strategists expect much of that to find its way -- temporarily, at least -- into carry trades in short-dated sovereign bonds. They see Italian bills benefiting particularly versus German benchmarks. But the big boon for Europe's government markets is the 1.35 trillion euro pandemic emergency purchase program, which the ECB last week expanded by 600 billion euros. Even this unprecedented effort can hardly keep pace with the costs to member states of dealing with the pandemic. Last week alone, they raised 32 billion euros from syndicated bond sales, pushing total issuance in Europe to 1 trillion euros so far this year. Citigroup analysts told clients that even with the additional firepower, the ECB's PEPP will fall well short of the likely surge in the bloc's debt supply. ... BOE Gets ToughWhile the ECB is striving to exceed expectations, the Bank of England's latest moves were possibly more remarkable, for what it didn't do. The central bank boosted its government bond purchases, by 100 billion pounds ($124 billion). But that wasn't exactly the largesse the market was looking for: the BOE is now also slowing weekly buying as market pressures have subsided. The 745 billion pounds remaining in the total asset-purchase program will see it run to year end, and there's no indication it will be renewed. This was wrenching news for the market, sending long-dated yields sharply higher, steepening the curve, and wiping out bets on negative rates that had sprung up a few weeks ago. Those positions owed in part to BOE chief economist Andrew Haldane's comments last month that appeared to flirt with a sub-zero rates policy. Haldane was also the lone dissenter in the BOE's decision, favoring no increase in QE.  Meantime, the risks of COVID-19 remain. "The U.K. was among the last to enter lockdown. It is also taking only hesitant steps to exit from it. This suggests the UK. may lag other major economies in the months ahead," rates strategist Jacqui Douglas writes with colleagues at TD Securities. The team expects the central bank will be pushed to an additional 50-billion-pound expansion of QE in November, likely to run though the first half of next year. Bonus PointsBig banks are recognizing Juneteenth with shortened workdays A $1 trillion cash hoard holds the key to the fate of risk assets  The Fed's hearings on Capitol Hill are rooted in a failed 1978 pledge to fix inequality The BIS is worried about the world's addiction to dollars JPMorgan sounds a warning on market correlations at 20-year highs  Applying "Meatballs" logic to fears of a supply/demand imbalance in the world's largest market

Strong candidate for Bloomberg headline award Kings of controversial debt trades cry foul when on other side |

Post a Comment