Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that is starting to appreciate the value of a metacognitive approach to macro analysis, modeled on Powell's "not thinking about thinking..." –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter. Mood SwingsThe hopes that sent risk assets soaring last week are souring as the shadow of a possible second wave of the pandemic in the U.S. looms over markets. As the number of Americans infected with covid-19 pushed above two million, reports that Texan officials are close to reinstating a lockdown fanned investors' worst fears for the economic recovery. The S&P 500 Index suffered a string of losses and a near 6% drop Thursday, the steepest since March, reversing most of the past month's easing in broader market strains, as reflected in U.S. financial conditions.

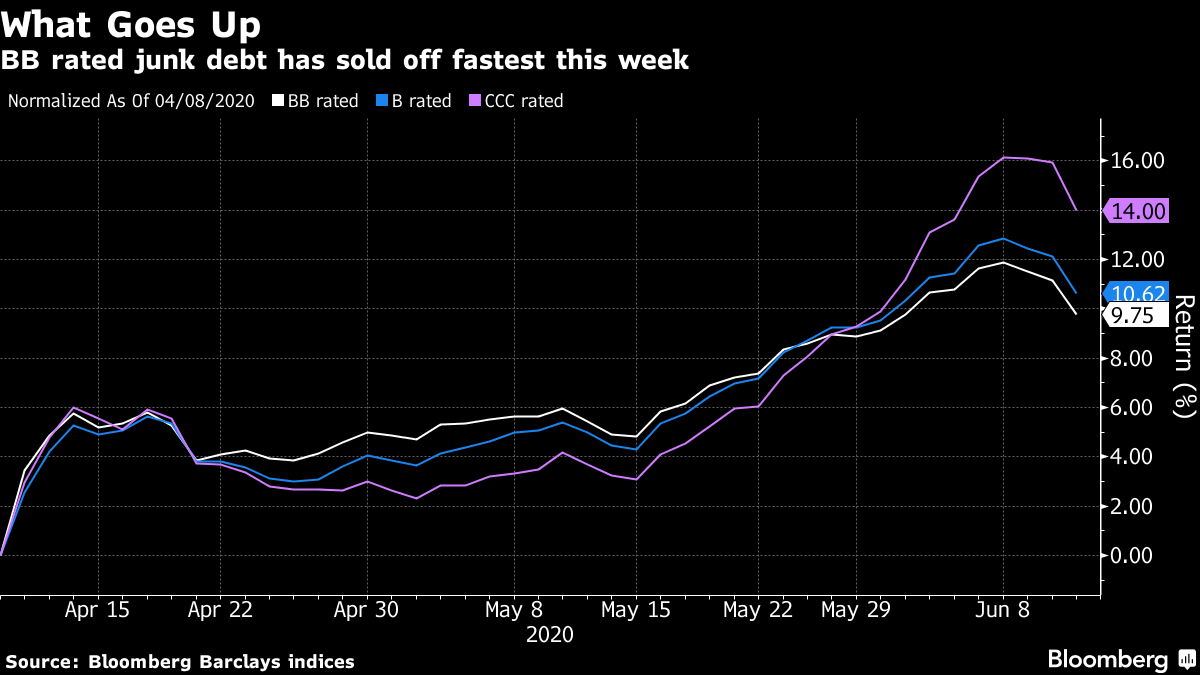

The flight to Treasuries pushed yields back toward their lows of the month. But the about-face in corporate bonds, which have been on a Federal Reserve-liquidity-fueled tear for the past couple of months, could see the central bank delving deeper into controversial credit-market support facilities. The cost of insuring investment-grade corporate debt against default climbed this week and 10 companies dropped plans to issue bonds in a single day. The rout threatens a dramatic reversal of the record back-to-back flows returning to U.S. credit funds this month. Junk-bond funds are looking particularly shaky after notching up an 11th straight week of growth, according to Refinitiv Lipper data, with the lowest-quality debt taking the brunt of selling over the past few days.  All this is likely to stir more talk of the zombie apocalypse -- the fear that the Fed's programs are simply going to prop up companies that would otherwise have been culled by this crisis. The living dead in this case are firms whose revenue won't cover their debt service costs. The argument goes that while they stumble on, unable to thrive but also not dead, they limit the success of healthier competitors.

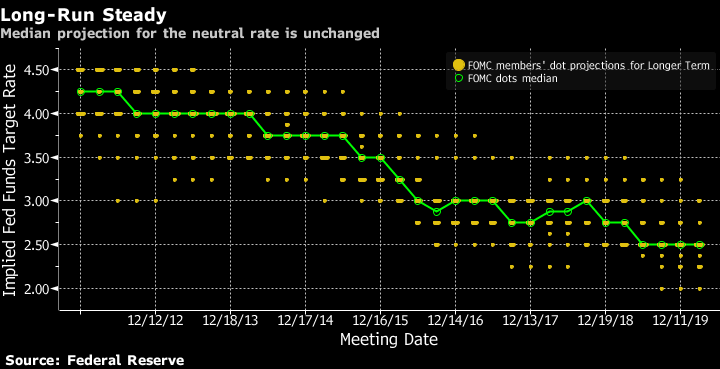

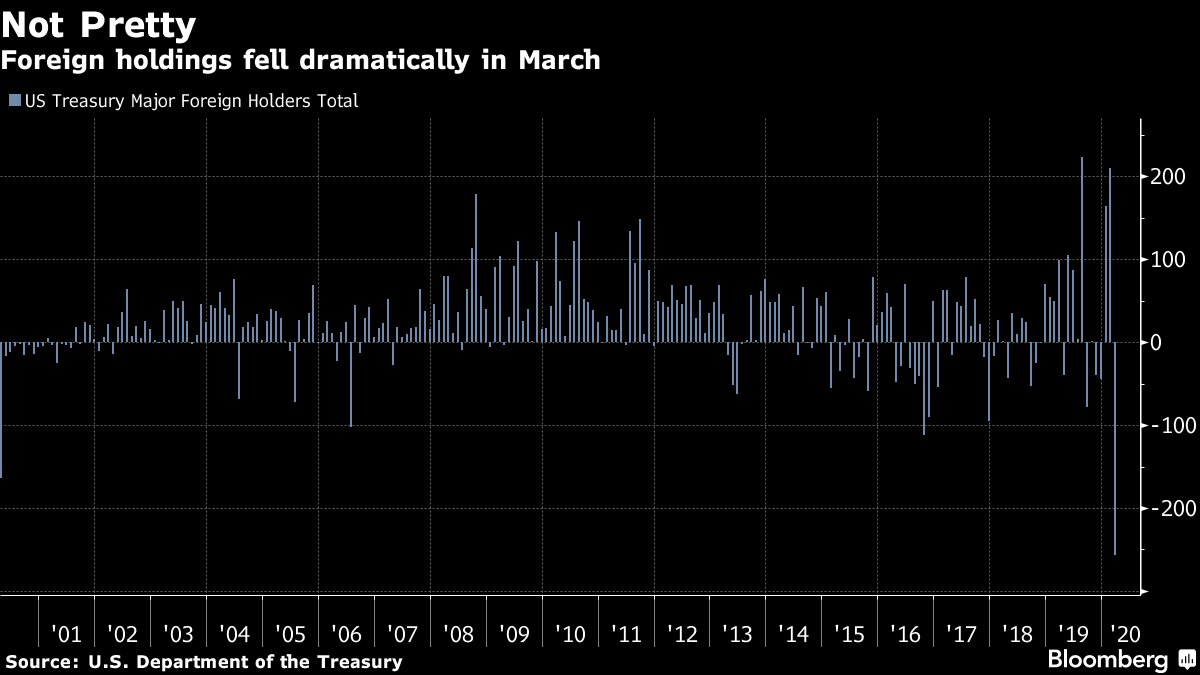

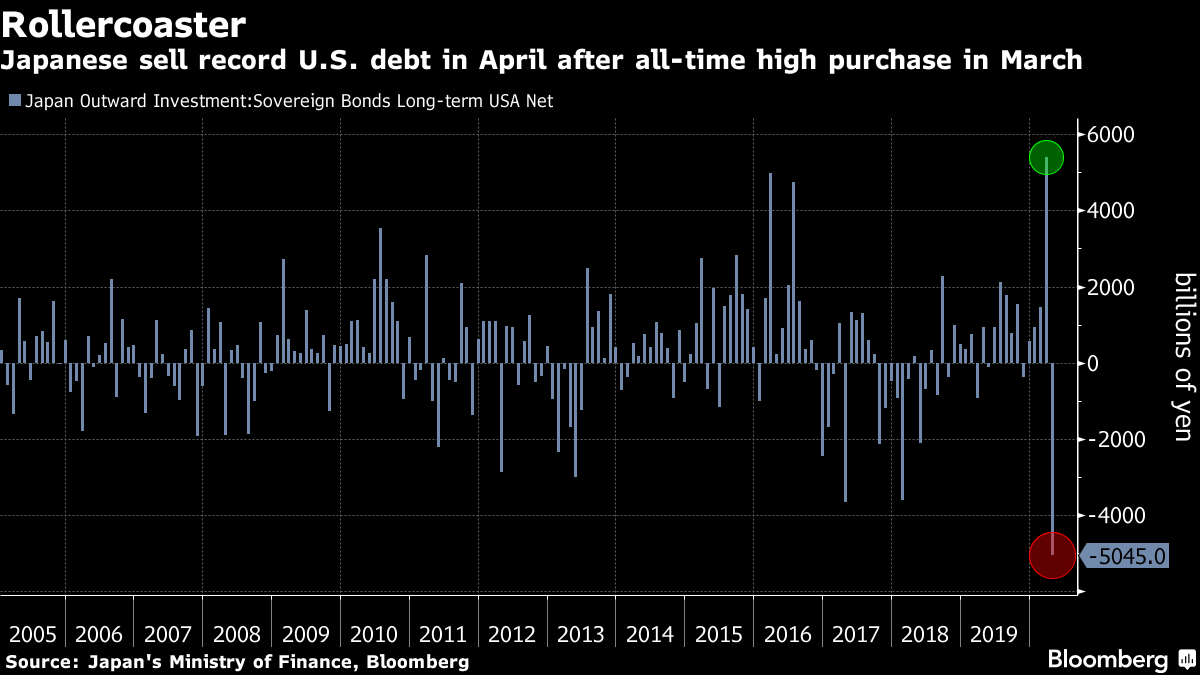

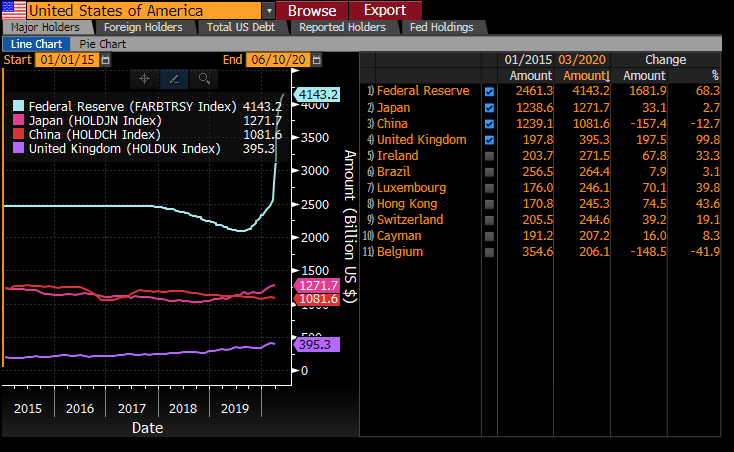

In short, says Deutsche Bank economist Torsten Slok, keeping unproductive companies going "ultimately lowers the long-run growth rate of the economy." The share of companies in the U.S. with an interest-coverage ratio of less than one has risen from roughly 2% in 2005 to close to 20% today, by Slok's reckoning. And he sees the trend persisting "given the Fed's commitment to keeping rates low and the ongoing support from the Fed to credit markets." Trading the FedForget those quaint assurances of patience, lower-for-longer, tinkering with asset purchases -- this is 2020. "We're not even thinking about thinking about rate hikes," Fed Chair Jerome Powell said Wednesday. The Fed isn't giving much away about what IS on its mind, beyond maintaining at least its current pace of asset purchases. Policy makers got a briefing on yield curve control, Powell said, but whether it turns out to be useful for the U.S. is still an "open question." So that investor debate may now be on ice. About last month's labor market turn, the Fed chair said that "we don't know what that means." Treasury traders made what they could of all that. Most piled into the five-year, convinced that the target rate is stuck at zero for at least the next two years, as reflected in the new dot plot of FOMC projections. The resulting outperformance is pushing investors further out the curve, shrinking spreads between short and long-end yields. The five- to 30-year stretch is the flattest since late last month, around 110 basis points early Friday Asia time, compared with a peak of 128 basis points last week. JPMorgan Chase strategists are hanging on to their 5s30s steepening call over the medium-term, "as the current pace of Fed purchases is not enough to offset the increase in monthly duration supply" over this quarter. (The Treasury is aiming to extend the weighted average maturity of its debt back to pre-pandemic levels.) But Ed Al-Hussainy at Columbia Threadneedle is among those disagreeing that the curve has further to climb. In this easing cycle, the relationship between the five-year and the 10s30s curve has broken, as the short-end rally is limited by the zero bound. "If you're anticipating steepening you really have to bet on the long end doing something extraordinary," and that's unlikely while the Fed is still mopping up Treasury issuance at a rate of at least $80 billion a month. One big curiosity for some in the Fed's messaging was the elevation of the longer-run interest rate projection. That remains at 2.5% -- a level HSBC's Steven Major described as "borderline ridiculous." But it's most likely just too soon for policy makers to make any adjustment, as the past week of highs (better-than-feared payrolls report) and lows (stirrings of a possible second wave of Covid-19 cases) attest. At this point, though, moving the long-run rate down would essentially be an admission that they "were defeated by the secular forces of the economy -- and the history is, they'll just want more evidence of that," says Al-Hussainy.  Median projection for the neutral rate is unchanged Four Tales of UST DemandThe renewed haven buying that drew the global benchmark yield back from last week's highs near 1% is validation for Treasury bulls. It's also reassurance that demand can keep up with the breakneck pace of supply. That remains a critical question for the Treasury as it plows on with fundraising for a multi-trillion-dollar effort to avert a generation-defining recession. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that pandemic relief will swell the deficit by $2.2 trillion this fiscal year. There are myriad ways to look at the measures of, and forces on, supply and demand. One big one is the Treasury International Capital data that show monthly changes in foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries (the next batch, for April, is out Monday). It might as well be a Rorschach test, given the variety of interpretations, but this latest one showing an historic drop at the peak of the pandemic-driven market turmoil looked menacing.  Also alarming was this balance of payments data from Japan, which holds the largest share of U.S. Treasuries outside the country. Investors from the country dumped a record amount in April, turning to higher-yielding Italian and Australian bonds.  On the other hand, the timing around the end of the Japanese fiscal year suggests these flows "could be more idiosyncratic than beginning a new trend," said BMO Capital Markets strategist Jon Hill. And the drop in dollar-yen hedging costs over the past couple of months may also help support Japanese demand.  Moreover, the pile of U.S. government debt the Fed holds in custody for international accounts has grown steadily since mid-April. The Fed's efforts to head off a dollar-supply shortage -- via swap lines and repos -- have been successful in preventing any heavier liquidation of Treasury holdings, which means "central banks are now in a position where they are able to restore their former securities positions," according to Jefferies economists Tom Simons and Aneta Markowska. In the meantime, the debate over whether Treasuries are still a destination of choice for international investors is largely moot. It's all about the Fed.  Bloomberg Bloomberg Bonus Points

"We can't shut down the economy again," says Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin.

Keep up with the latest on the European Union's recovery fund The VIX curve wants a word with you. Won't take a second. High-emission vacations lead to trouble in a rainforest far, far away.

China's power giants prepare for world's biggest carbon market

Treasury rally is so not done yet...  Who's blowing bubbles? Not the Fed. |

Post a Comment