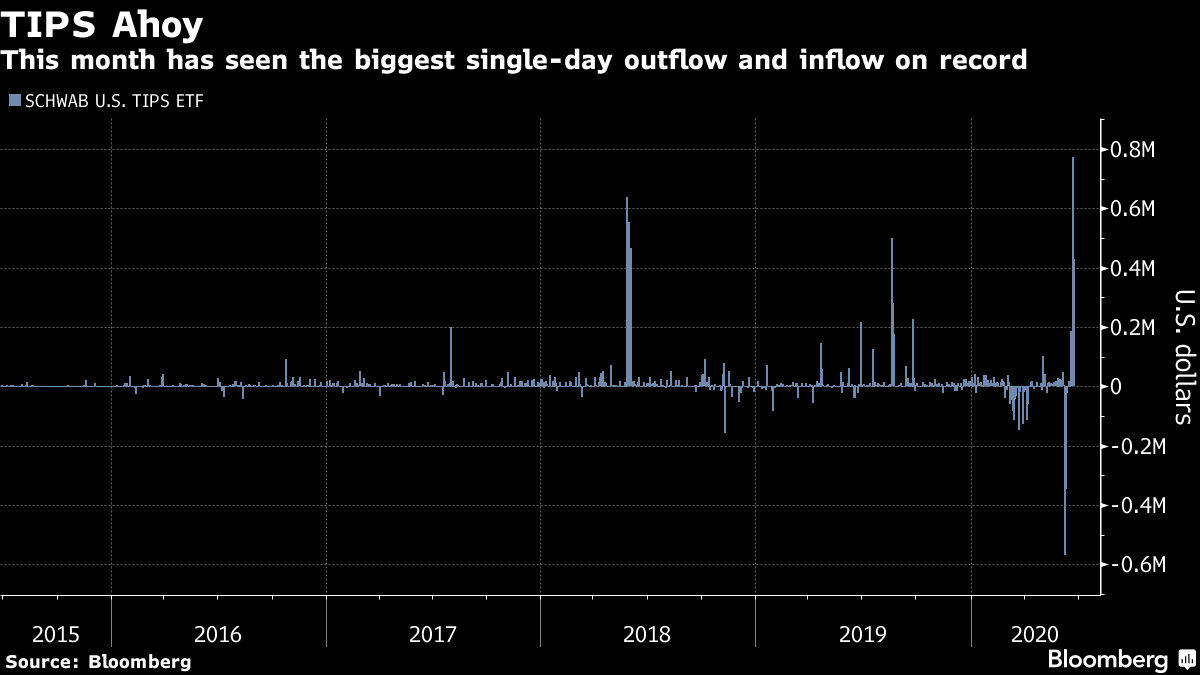

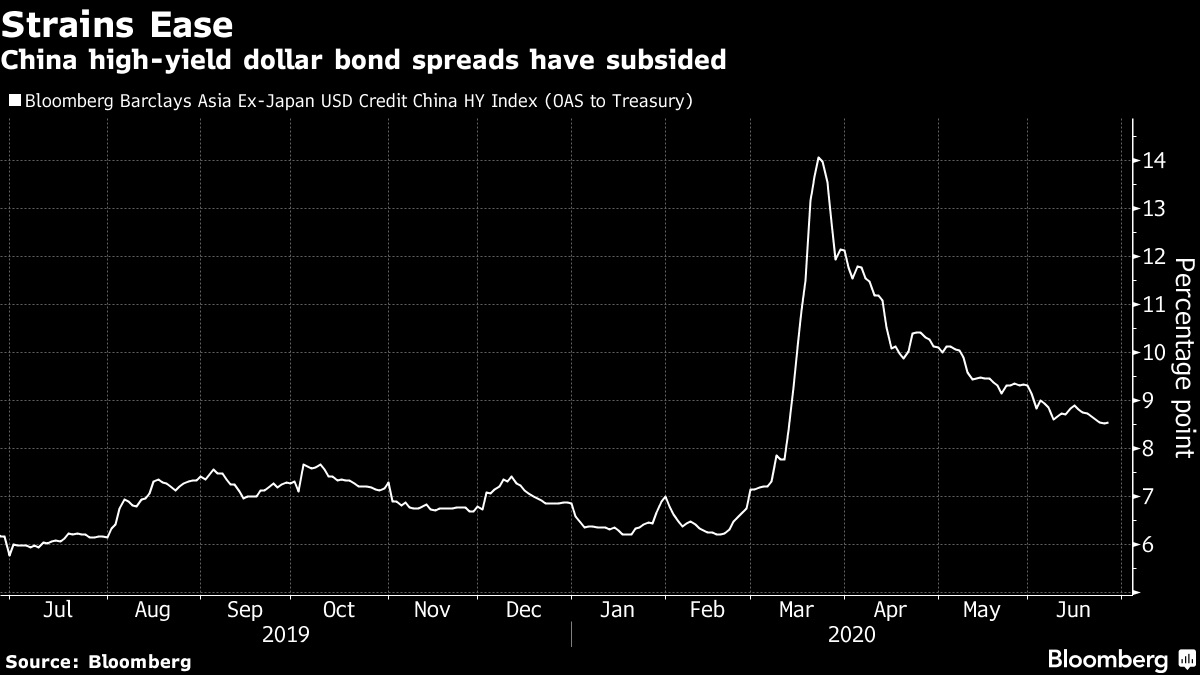

Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that is pure Helvetica at heart. –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter. Stocks and bonds find common groundFor a dashboard of how the Federal Reserve has powered down the U.S. rates market, look no further than what's happening with real yields and volatility. And that should resolve the supposed conflict between equity-market optimism and the gloom reflected in government bonds. Real yields are considered a pure read on growth as they strip out inflation, and the 10-year touched minus 0.70% this week, the lowest since early March. If you look past the extraordinary turbulence of that month, it's the lowest since 2013, just before the Fed dropped its first big hint of tighter policy to come and sparked the "taper tantrum". This isn't simply a dismal growth outlook, or equities wouldn't be where they are. Stocks and government bonds are kept aloft by the same conviction -- interest rates are staying put at the zero-bound for years to come. "The Fed must be happy -- well, at least pleased that the market has heard them," said Priya Misra, head of global rates strategy at TD Securities in New York. "Low real rates are good for risk assets -- it explains the apparent disconnect between stocks and bond prices." Low real rates in the U.S. are strong medicine for a swifter recovery globally too, as they weigh on the dollar, to the benefit of emerging market economies with hard-currency debt. The greenback has already shed more than 6% from the peak it hit in March that was triggered by haven flows and a shortage of dollar funding. Another encouraging sign for policy makers -- the slide in real rates is coinciding with a rise in inflation expectations. It's a climb out of a deep hole, not a rebound -- a key distinction given the inevitable scolding from some quarters about the risks of ultra-loose monetary policy stoking runaway inflation. (There was no sign of that in the recovery from the global financial crisis -- a point often made, but worth reiterating to fend off stimulus skinflints.) As the full impact of the pandemic and economic shutdown took shape, a deflationary slump seemed the bigger threat, but that looks to have been averted.  The about-face in sentiment is evident in this month's record-breaking traffic in one of the largest exchange-traded funds for inflation-protected bonds. Assets in Schwab's U.S. TIPS ETF grew 20% over the past five days, which included the largest single-day inflow ever. That came barely two weeks after its largest-ever outflow.  There's no shortage of evidence to support the case for an upward trend in inflation. The destruction of global supply chains, which have in turn exacerbated shocking food shortages, lingering optimism about a V-shaped recovery, and -- not least -- the Fed's own strategic review to sharpen up its act on hitting its 2% target. It's just that there are a lot of well-worn counterarguments -- take your pick from the structural forces of an aging population and declining immigration, advances in technology, or anything Larry Summers has ever written. But the more powerful display of the Fed's effectiveness is in the rates volatility market. The term structure here has collapsed, says Bloomberg Intelligence global derivatives strategist Tanvir Sandhu, in a far more dramatic market response than the Fed got with its forward guidance in 2011-12.  This tranquility is emboldening investors to pile into risk assets -- but the rates market surface may not stay so glassy for long, if corporate bond defaults start piling up. The default rate for speculative-grade companies could triple by next March, according to S&P Global, and more companies than ever are in jeopardy of losing their investment-grade ratings. That's a compelling prospect for volatility mavens: Investors may be well advised not to fight the Fed, but fundamentals just might. The International Monetary Fund put it in somewhat exasperated terms, in revising down its economic projections this month: "Investors seem to be betting that lasting strong support from central banks will sustain a quick recovery even as economic data point to a deeper-than-expected downturn." Defaults on displayAnother apparent contradiction is the one unfolding in China with respect to corporate defaults. The economic shock of the shutdown was expected to see the world's second-largest bond market notch a third straight year of record failures. Instead, the total value has dropped almost a third from 2019, to 38 billion yuan ($5.4 billion), by Bloomberg calculations -- that's in the $4.5 trillion onshore market. The stress is playing out, however, in the offshore market, where dollar-bond defaults have surged almost 150%, to $4 billion. The divergence highlights the extent to which regulators and the central bank have succeeded in supporting the domestic market, where weaker borrowers have managed to refinance. That's even as China's leadership has surprised some market watchers with its gradual approach to stimulus -- wary of a repeat of the massive debt surge a decade ago that left bad loans trailing in its wake. By comparison, Chinese firms have been far less able to access cheap funds or forbearance overseas. Chinese dollar bonds slumped in March, led by the country's heavily indebted property developers, and the rout gathered momentum as leveraged investors faced margin calls, according to some traders. High-yield spreads have since recovered much of their widening, but the attrition is clearly still playing out.  This could be read as something of a setback in China's efforts to modernize its bond market into more of a Western-style, market-driven exchange where credit is priced on risk. The escalation in onshore defaults in recent years was, after all, a sign that authorities were finally allowing them to happen, while at the same time pushing for bondholder protections. That said, the West's markets have themselves changed under Covid-19, with central banks now providing major backstops. So much for moral hazard. Read: Here's how fast China's economy is catching up to the U.S. Bailey calls the shotsIt was a shot across the bow. Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey put the money market fund industry on notice that the central bank won't hesitate to unwind its balance sheet. That's a pretty radical statement in this day and age, especially after what happened in the U.S. back in 2018-19, when money markets effectively caused an end to the Fed's plans for an "automatic pilot" approach to reducing its portfolio. Bailey warned in a Bloomberg Opinion piece this week that the central bank's reserves aren't candy. "The financial system mustn't become reliant on these extraordinary levels of reserves," he wrote. Rather, its "weaknesses" need to be addressed, singling out the role of money market funds, "and the risks to financial markets that they posed at the height of the disorder." The piece offered a flavor of forward guidance, a sequence for withdrawing support that would start with trimming the balance sheet before moving to raise interest rates. It also gave more color on the hawkish sentiment behind the BOE's move last week to increase its bond-buying program, while signaling it will likely peter out by year-end. The UK's multi-trillion dollar money-market funds are in the BOE's line of fire as they struggled during the crisis to sell assets to meet redemptions, despite supposedly investing in relatively safe, easily-traded securities. Their tribulations had some resonance across the pond. A massive outflow from U.S. prime funds, which tend to invest in slightly riskier short-term debt, threatened to destabilize the commercial-paper markets that cover key financing for U.S. companies, such as payrolls. In a March interview with the Wall Street Journal, former head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Sheila Bair opined that "It's just frustrating that we never really fixed this stuff to begin with." She added that "the industry lobbyists came in and persuaded regulators to do half measures. And we're back in the soup again." That said, Bailey's message did have a sweet chaser, as BOE alumnus Andrew Sentance highlighted in a tweet that negative rates -- a potential death knell for the industry -- are likely off the table. "If changes in #QE are now the main policy lever, the implicit signal is that negative rates are off the agenda," the former official posted. Deal of the centuryAustria sealed a deal this week that would make the U.S. president's eyes water, and may inspire its European neighbors. The country raised 2 billion euros ($2.2 billion) with its second 100-year bond sale, at a rate of just 0.88%. That compares with a 2.1% coupon on its inaugural century bond in 2017, which has since almost doubled in price and delivered an 85% return for investors.  Austria's latest venture is tapping searing global investor demand for safe, positive-yielding assets. It's also a standout in the euro zone in terms of extending its debt profile. The weighted average maturity of bonds sold in the peripheries, as well as semi-core countries France and Belgium, actually fell in the second quarter, note ING strategists including Padhraic Garvey. "The focus has been to raise vast amounts of cash quickly in the least disruptive ways, particularly given some countries' already precarious debt ratios," they write. Meantime, the eye-watering duration risk of the Austrian bond means investors could lose more than two-thirds of their money if the yield rose to 1.88%. That doesn't seem outside the realm of possibility in a decent recovery. Jon Hill at BMO Capital Markets points out that loss would be even bigger if it weren't for the century bond's high convexity -- its price rises faster when yields decline than it falls as yields go up. And that's an attractive quality in a broad portfolio, as a hedge against volatility. But that doesn't mean the U.S. Treasury should necessarily make another attempt at joining a 100-year bond club that includes Mexico, Argentina, Oxford University, and Coca-Cola. For the federal government, securing sufficient demand for regular and reliable issuance in the world's top benchmark debt market is paramount. "The illiquidity of a 50 or 100 probably overwhelms the convexity value," says Hill. "Treasury certainly made the right call going with 20s." Bonus PointsWhat does the world think about the U.S. virus response? What do clever people think about how COVID-19 will change the world? Racism Has Shaped the Fed's Leadership: Narayana Kocherlakota Robinhood crowd misses a trick Five ways to get through summer if camp is closed (for those living at work) Only a trickle of finance workers are returning to NYC Goldman shot the serif |

Post a Comment