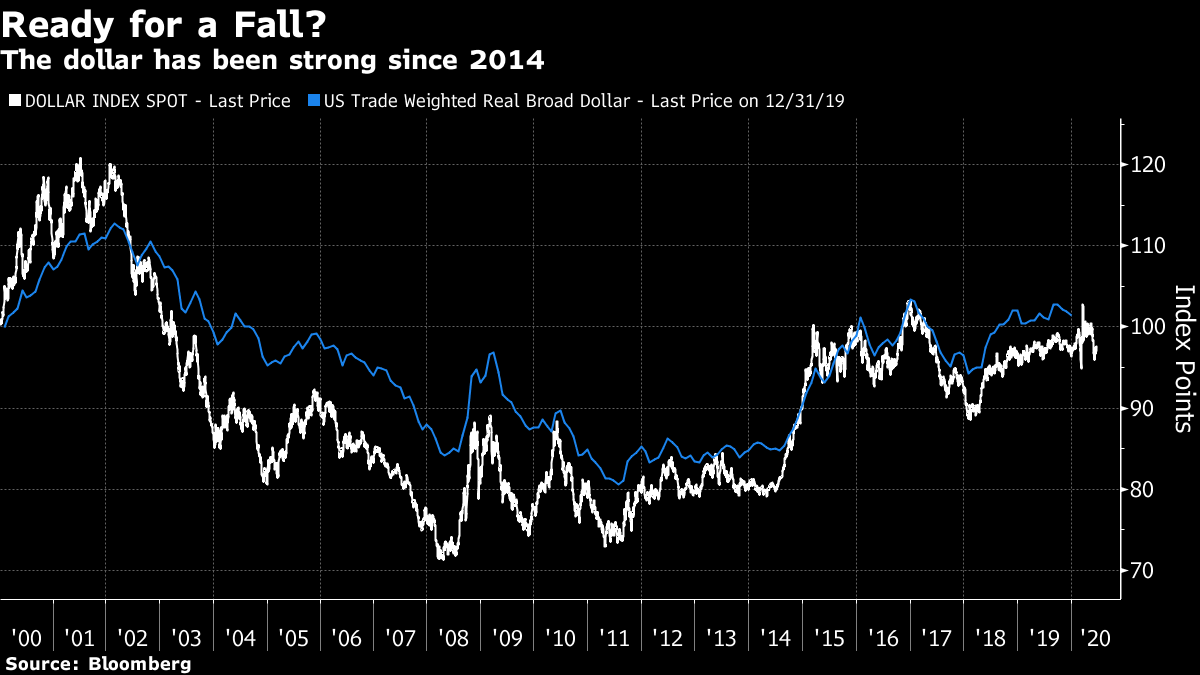

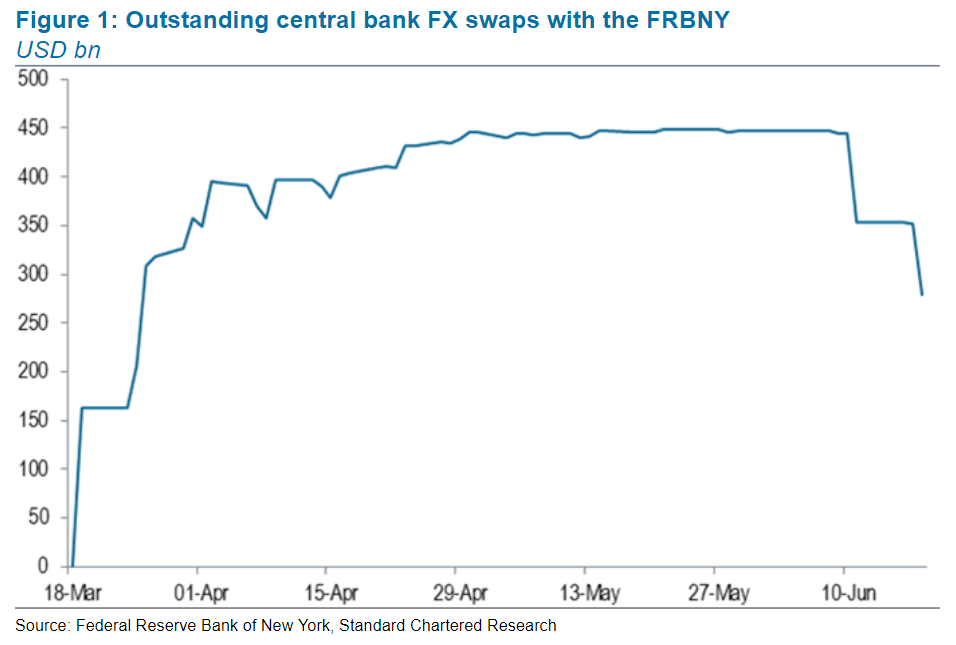

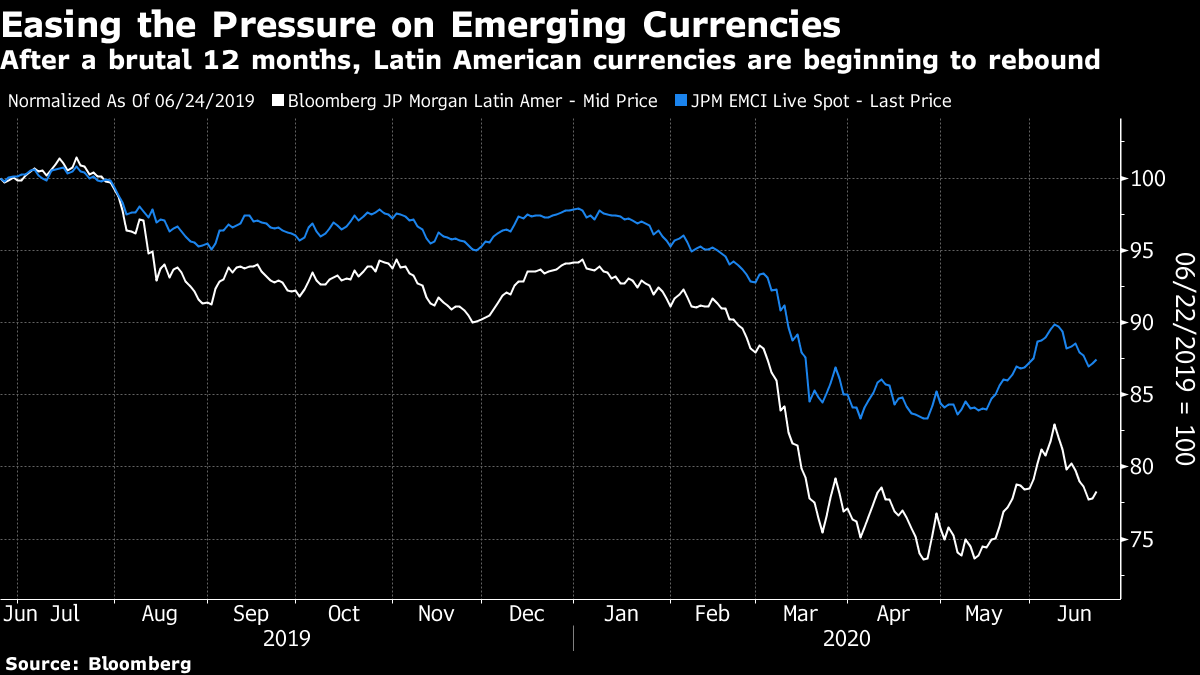

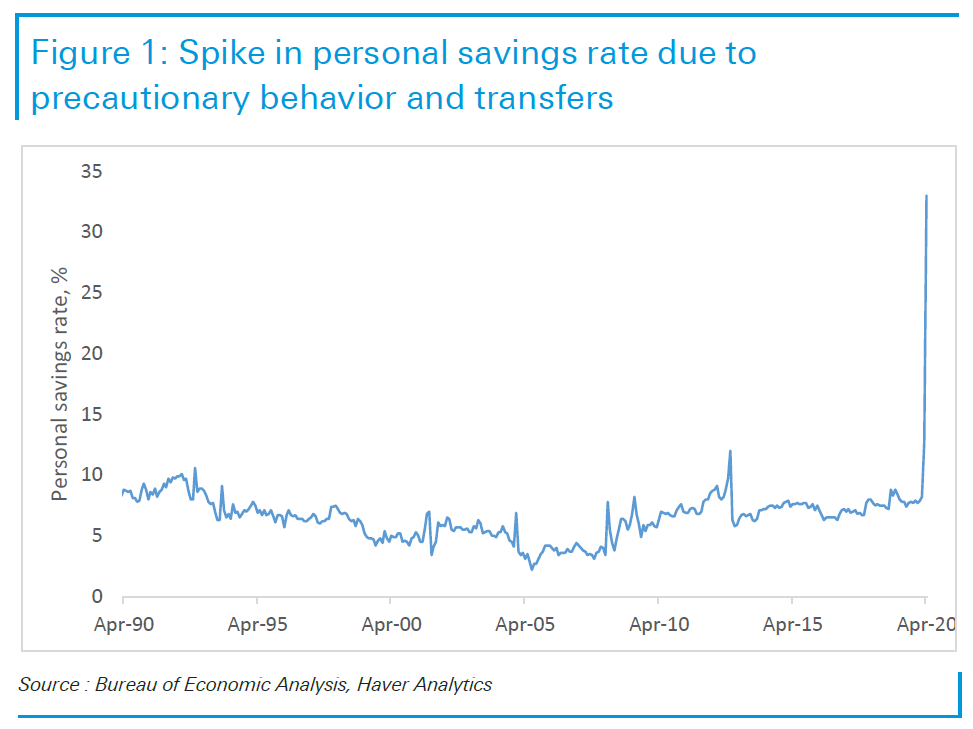

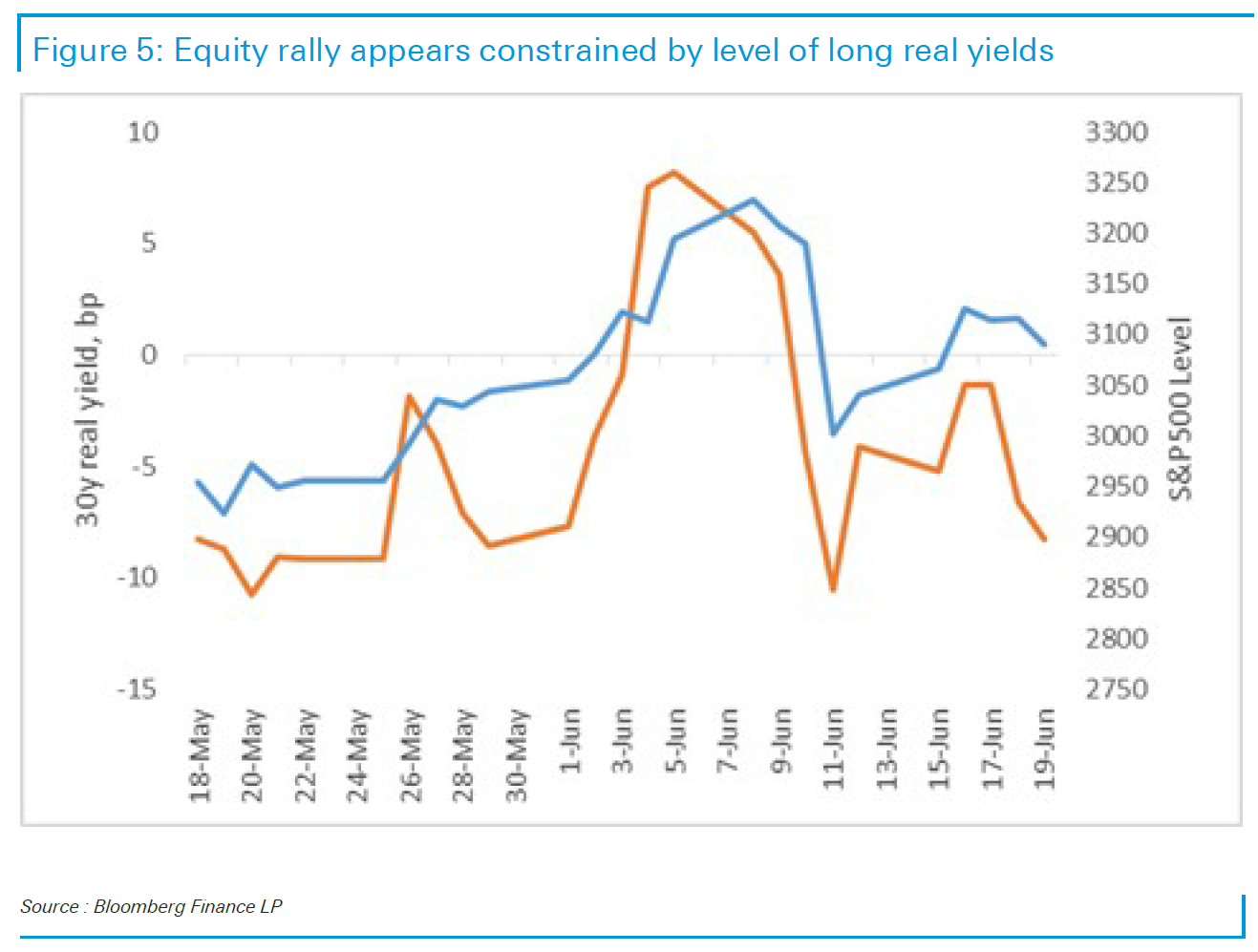

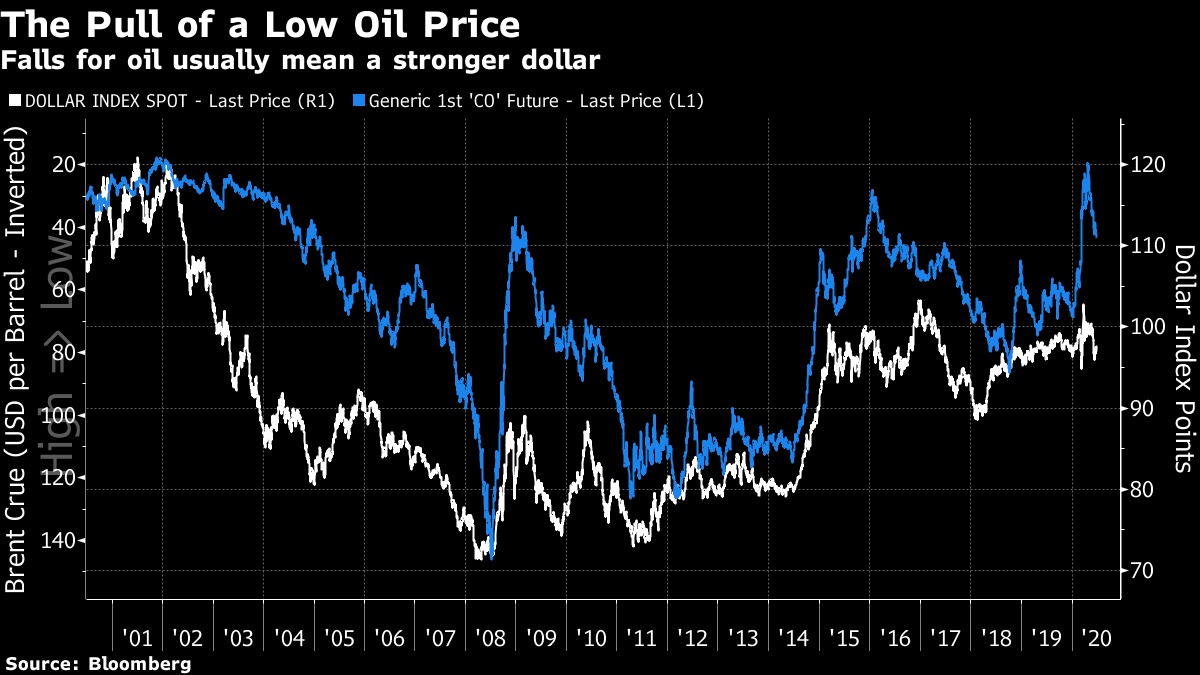

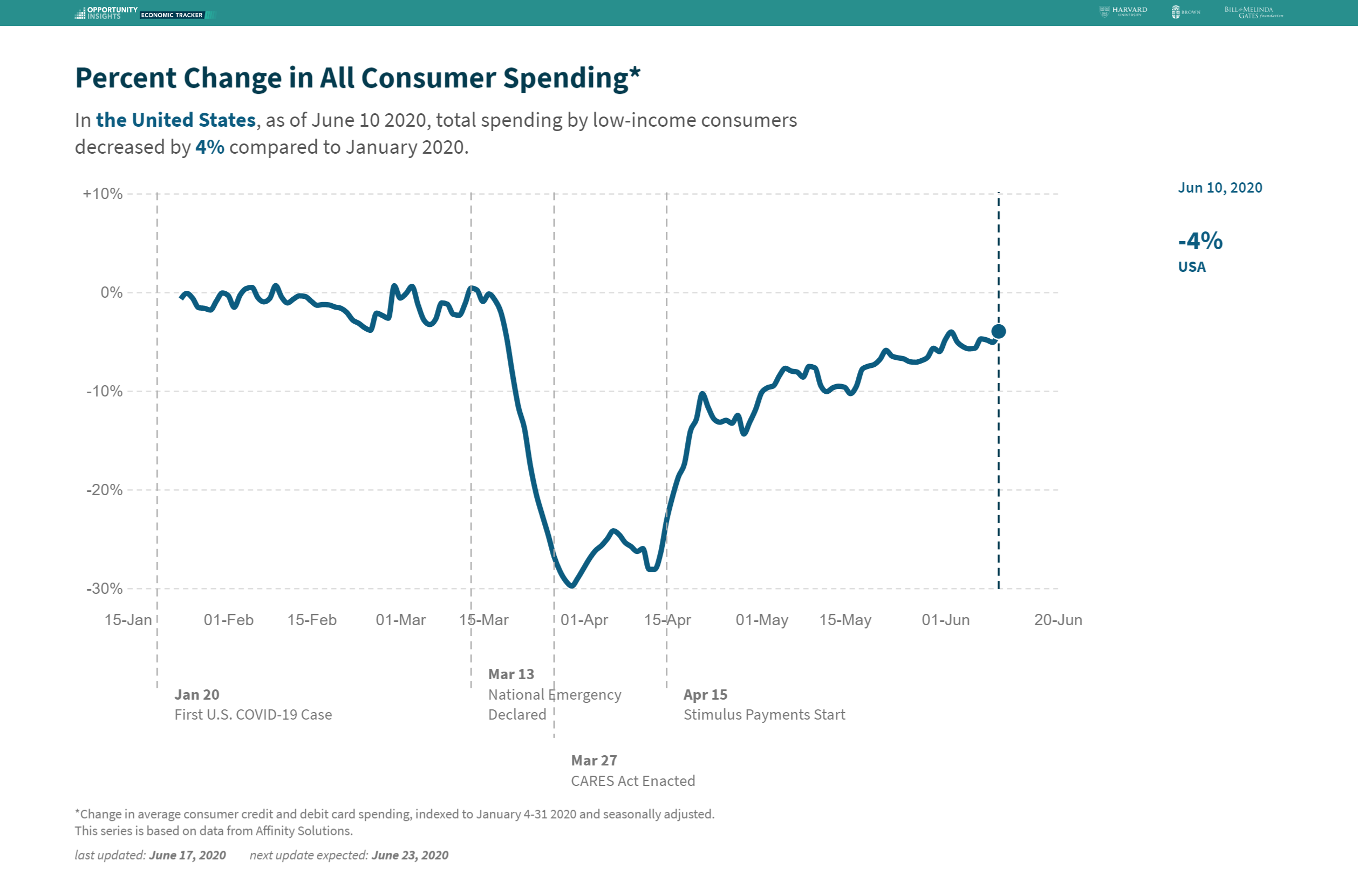

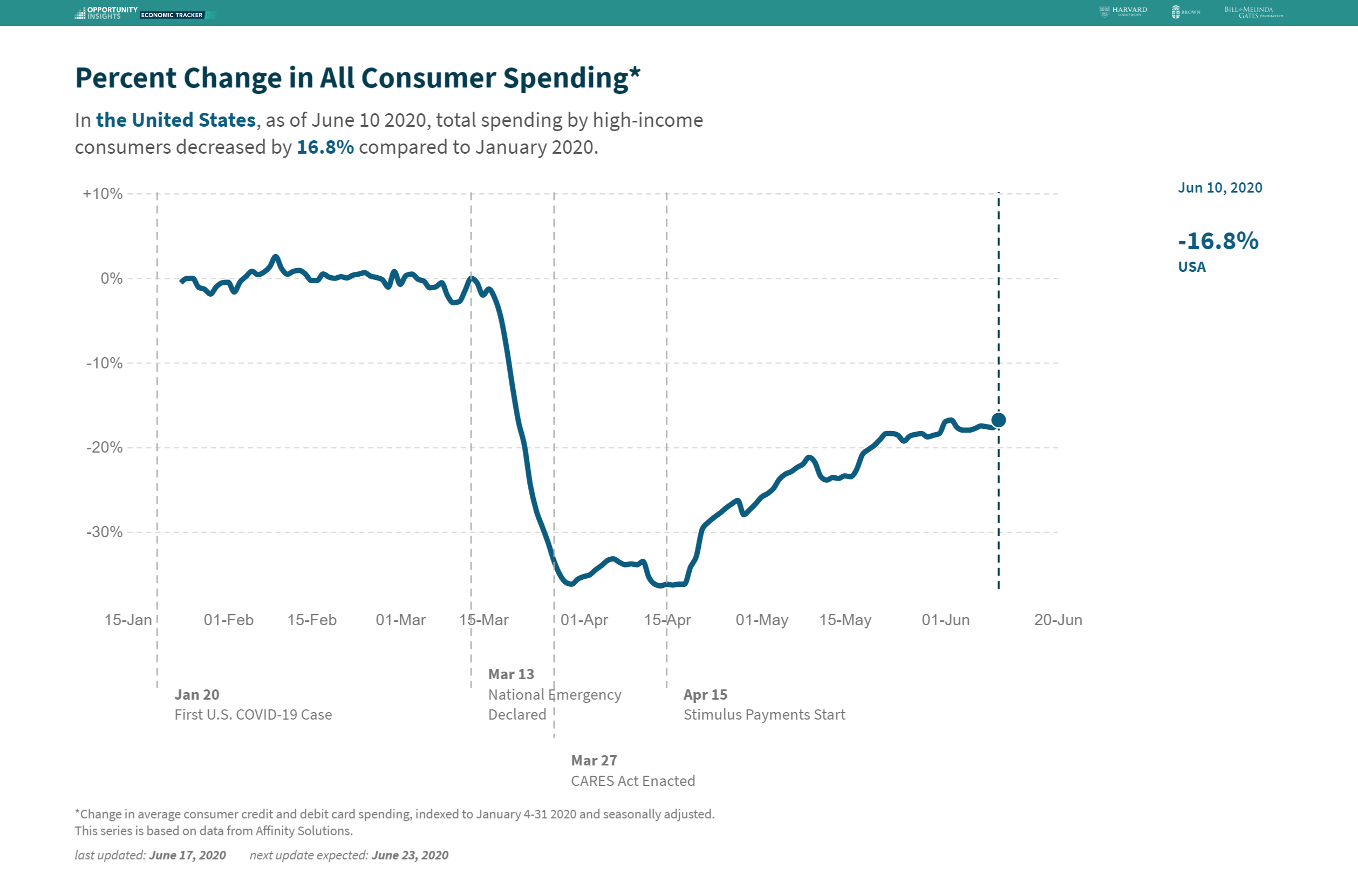

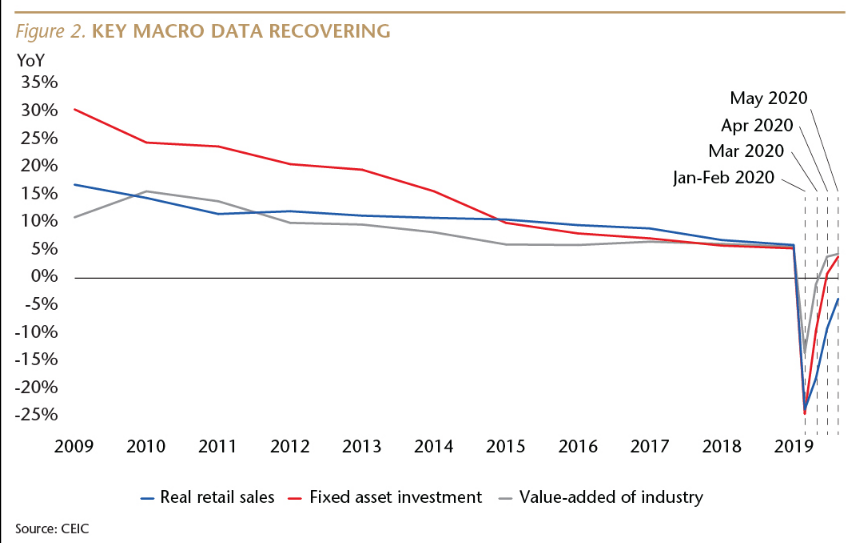

A Strong Recovery Sign It looks as though the time for a renewed dose of dollar weakness is here. If it happens, that will be great news for many. On both a real basis (taking inflation in different countries into account) and in nominal terms, the dollar is roughly where it was 20 years ago. After various switchbacks during the shocks of the first half of this year, it also appears to be in a downward trend:  One reason for relative weakness is extremely positive, which is that the shortage of dollars in the rest of the world is growing far less acute. Back in March, the Federal Reserve started offering foreign exchange swaps to a number of other central banks in friendly nations, as they suffered a dollar funding squeeze. They made great use of this at first, but demand for dollars had flattened by the end of April, and this month it has begun to fall, as made clear by this chart from Steven Englander of Standard Chartered Plc:  Englander also points out that the slight reduction in the size of the Fed's balance sheet last week was driven primarily by the drop in outstanding foreign exchange swaps, and didn't imply any dwindling in the Fed's determination to keep markets afloat with liquidity. This easing in pressure can be seen in the recovery of emerging markets currencies in general, and Latin American currencies in particular, as shown by the JPMorgan indices:  Emerging markets foreign exchange dropped traumatically during the worst of the Covid crisis. The partial recovery is happening even though countries like Brazil, Mexico and India are now in the front line of the health crisis. Another key reason for dollar weakness is that the Fed seems to be committed to keeping longer yields low. The differential of Treasury over German bund yields dropped sharply in the first weeks of the crisis, and has now stabilized at a little above 100 basis points — a level it hadn't previously seen since 2014. All else equal, this weakens the dollar, particularly compared to the wide differentials of two years ago.  There is also reason to hope that the Fed will need to do more to keep longer yields under control. As the following chart from Deutsche Bank AG demonstrates, the personal savings rate has risen remarkably since the crisis:  If the Fed wants the economy to grow, it plainly wants that savings rate to reduce and for money to find another home. That implies that it will try to keep real long-term yields as low as possible, and ideally negative. On Monday, 10-year real yields hit their lowest level since early May 2013, on the eve of the so-called taper tantrum, so the pressure to maintain low real yields continues. As this chart from Deutsche Bank shows, there has also been a distinct link in recent weeks between 30-year real yields and the S&P 500 — which the Fed also appears to want to boost. With inflation expectations drifting upward as greater optimism about the future of the economy takes hold, keeping real yields negative will exert ever greater downward pressure on nominal yields. That will be dollar-negative:  The greatest caveat to the dollar weakness story comes from the oil market. The world has been on an informal "oil standard" for decades, with oil transactions denominated in dollars. This virtually guarantees an inverse relationship between the dollar and the oil price — the last big rally for the dollar came in late 2014 when the oil price, shown on an inverted scale in the chart, collapsed amid OPEC indiscipline. Oil is recovering at present after a second spectacular breakdown in OPEC discipline; if the recovery stumbles, it will put a limit on dollar weakness:  Another significant risk comes from the euro zone. If the EU and U.K. were to succumb to another loss of common sense in their Brexit trade negotiations, which must be completed by the end of this year, then the effect would be to take the pound and the euro out to the woodshed and shoot them. This would perversely strengthen the dollar. But for the time being, the Fed has shown off its great power, the dollar funding crisis is over, and it is in very many people's interests to weaken the dollar. That, after all, makes American corporate profits look good, and strengthens exporters, as a U.S. election approaches. Inequality, Covid-19 Edition The Western world is returning to work after the Covid-19 crisis. Naturally, attention has been hogged by the effect that reopening is having on the virus. But a wild card is the gulf between the impact of the pandemic, and its related shutdowns, on rich and poor. The following charts come from Opportunity Insights, a website maintained by Harvard University and a group of other organizations that is tracking the reopening of the U.S. economy. It tends to ram home that this slowdown is unlike any in living memory. This is the percentage change in consumer spending since the beginning of the year among the lowest-income consumers. By June 10 it was down only 4%:  Now, here is the change in consumer spending in the nation's wealthiest zip codes. At the same time, it was down almost 17%:  For the poor, the need to spend is unchanged, and many are facing the end of emergency unemployment aid. For the wealthy, many have continued to make money as before, as they work from home, and the effect of Covid-19 has been to prompt an unplanned but massive increase in saving (which we saw in an earlier chart). Totally different phenomena co-exist in the same country as a result of the same crisis. Inequality has been around forever, and it has been deepening for decades now. But there is truly no parallel for an economy this bifurcated. In an interesting essay, Neil Shearing, chief economist of Capital Economics Ltd., ran down the possibilities: If involuntary savings amassed by the second group of workers are run down as economies reopen, then aggregate demand should recover, preventing the threat of the loss of employment and income for the first group from becoming a reality. This is a necessary – though perhaps not sufficient – condition for a v-shaped economic recovery. In contrast, if the rise in involuntary savings turns into a semi-permanent increase in precautionary savings – perhaps driven by fear of future outbreaks and the economic disruption they would create – then demand will be much slower to recover. In this scenario, unemployed and furloughed workers will eventually suffer a loss of income when the sticking plaster of government support programmes is removed. Under these circumstances, further discretionary fiscal stimulus would be required to prevent the economic recovery experienced in recent weeks from going into reverse. Shearing rightly suggests that what happens next will depend on confidence. In both China and the U.S. there is clear evidence that the economy is recovering. All of us are aware of disquieting signs that the virus hasn't been vanquished in the U.S. — but the signs of a true V-shaped recovery in China are promising (as shown in this chart from Matthews Asia):  In many countries, not just the U.S., there have effectively been two lockdowns, as Shearing puts it — for the rich and for the poor. I think he is right when he says that sustaining positive overall momentum for the economy will depend on "whether those fortunate enough to find themselves on the right side of the labour market schism now have the confidence to go out and spend." Survival Tips It looks as though we might have reached a tipping point in society's attitude to race and historic racial injustice. This has led to some very interesting inter-generational conversations in my household, and in those of many friends. What is interesting is that there has been acute cultural awareness of racial injustice, and of the other pressing issues of this moment, for at least a generation. The songs I was listening to when I was younger than my kids are now made it clear that youth culture was painfully concerned then. I don't have a good explanation for why all that concern failed to tip over into anything more concrete, or any good predictions for whether this time will be any different. For now, my suggestion to middle-aged colleagues is to play some of these songs when challenged by teenagers. If the issue is racism, try Racist Friend by the Special Aka; for police brutality, try The Guns of Brixton by The Clash; and if anyone thinks Greta Thunberg is something terribly new, try Electricity, a paean of praise to solar power, by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. All the musicians still living who made these songs are into their sixties. The issues they were complaining about seem as raw as ever. But at least you can prove to your kids that our generation cared. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment