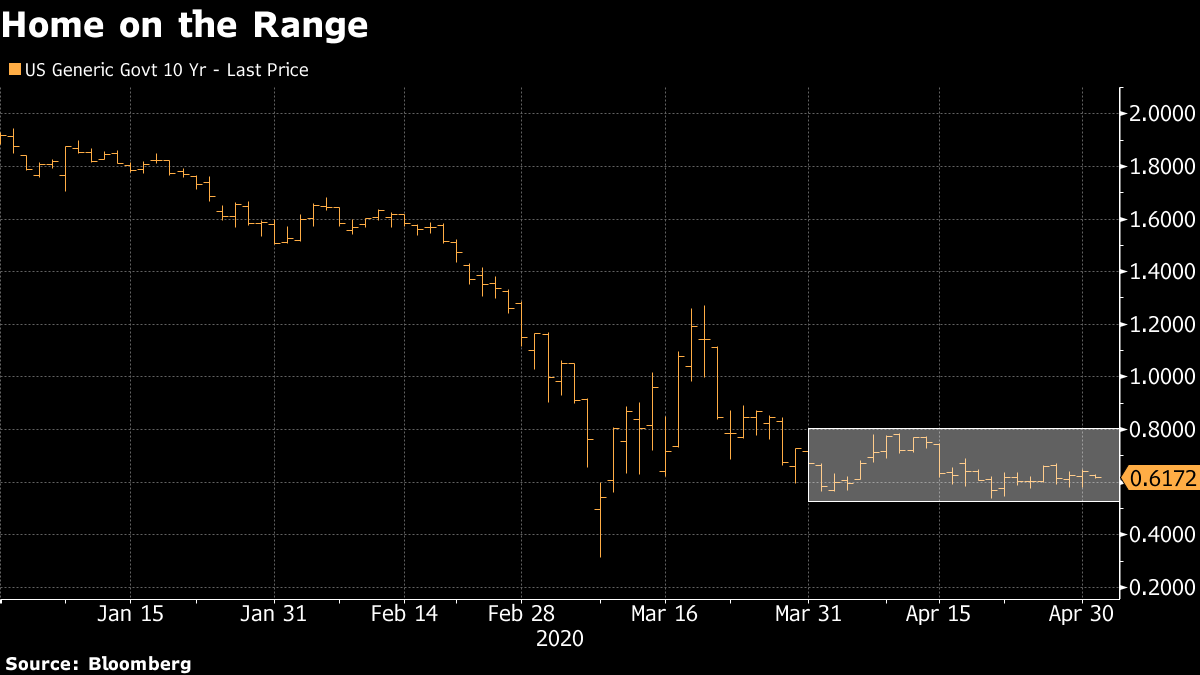

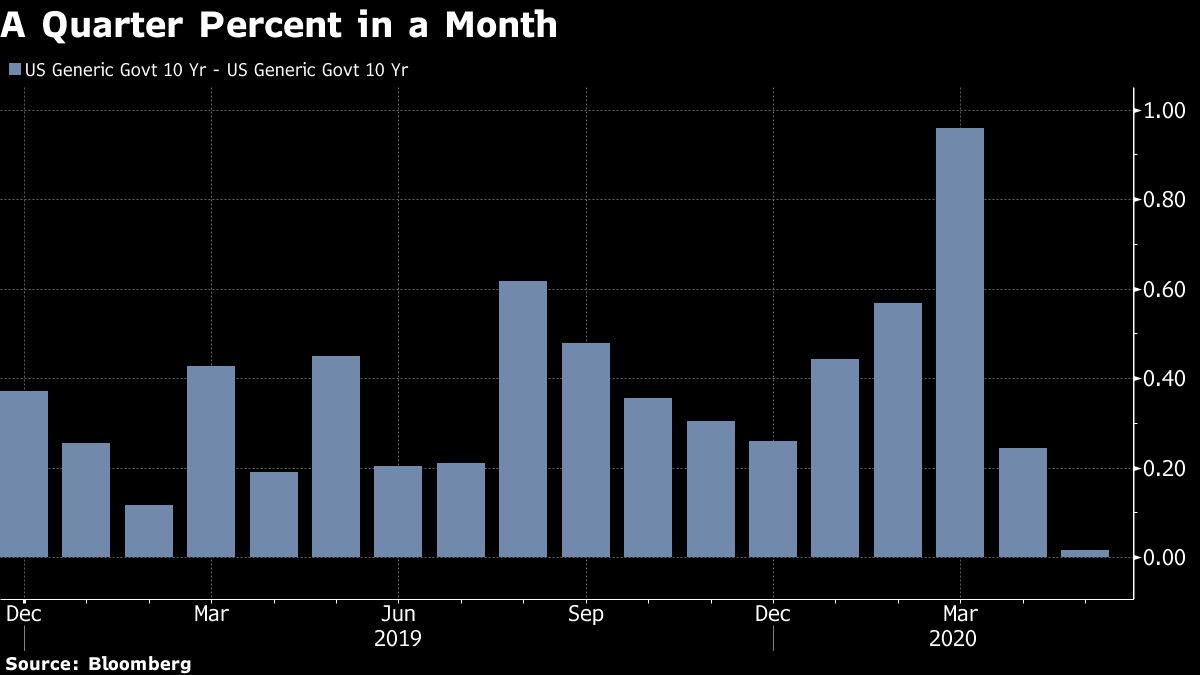

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that's looking at income chains and wondering where the recovery comes from. --Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter BAM! POW(ELL)! April has been a monumentally exciting month in financial markets. For markets that aren't Treasuries, that is.  The 10-year U.S. yield traded in a range of just 25 basis points, the smallest since last July. For two-year yields, it was the narrowest band since February 2019.  The lack of gyrations is in part a testament to the success of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and colleagues. The primary speculation, if not expectation, ahead of this week's policy meeting was for the Fed to provide more forward guidance: a firm commitment to keep rates near zero until it had made a ton of progress towards accomplishing its dual jobs-inflation mandate. Ultimately, Powell decided to forgo getting more precise in indicating how long rates would stay near zero. But he did point out that risks to the economy over the medium term loomed large (throwing cold water on hopes for a V-shaped recovery), and market participants didn't end up anticipating the Fed to be hiking any time soon. That's borne out by looking at the Eurodollar curve, which only starts to slope upwards late in 2022. It's unclear the extent to which non-calendar-based forward guidance could put more pressure on this curve than the economic realities of mass job losses already have.  Powell emphasized how much direct fiscal support would be necessary to mitigate worst-case scenarios. One thing he didn't mention was any hint toward how even an incredible scale of unconventional monetary policy wouldn't be a panacea for some companies teetering on the edge of the abyss. UBS Group AG strategist Matthew Mish pointed out that the enhancement of the Fed's Main Street Lending Program – updated after the policy decision – allows a much larger swath of distressed borrowers to tap Fed liquidity (eligibility more than doubled for one leveraged cohort, he calculates). The problem is the willingness to reach out for the helping hand. "Some firms will not materially benefit from the programs, and are likely insolvent," he writes. "The preferred outcome for some issuers will simply be to restructure an over-leveraged capital structure vs. maintaining one that is unsustainable and where the sponsor/management are beholden to demands from the Treasury/Congress." Which raises an interesting question: to what degree is there moral hazard in public-sector backstops if some companies prefer a default? Cannolis Are Tasty, Too The Great Rotation of European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde: Six weeks ago, she was saying that the central bank was not here to close the spread between core European yields and those on the periphery. Now, she's giving banks money to help make that spread disappear. The ECB introduced a new facility (PELTROs) that effectively gives banks no-strings-attached access to cheap funding. It's expected to result in a revival of the "Sarko trade," according to Ben Emons of Medley Global Advisors. That's a reference to the former French President Nicholas Sarkozy pointing out how the ECB's actions encouraged banks to embark upon a profitable carry trade by buying the bonds of their sovereigns. "The ECB was specific about the purpose of the PELTRO: 'providing an effective liquidity backstop'," Emons writes. "The new funding is therefore a 'giveaway' to banks who are free to use the funds to buy government bonds." It means that in effect, while the Fed is buying oodles of American government debt, the ECB is getting banks to do it for them. But because markets expected an enhanced asset purchasing program and got something else, the reaction was mixed to negative. While two-year Italian bond yields did reverse an initial jump to finish well lower, European bank stocks were hammered. It's as if investors ordered a Berliner and turned up their noses at the cannolis that appeared on their table instead.  The ECB also delivered a cut in the interest rate on the long term funding known as TLTRO loans. "The ECB's decision to lower the minimum TLTRO rate to -1% is absolutely massive," tweeted Banque Pictet's Frederik Ducrozet. "This will result in a net transfer of up to €3bn to the banking sector while ensuring the financing of the real economy." One primary critique of this approach is that it will somehow "crowd out" bank lending to other would-be borrowers. From Evercore ISI's Dennis DeBusschere: That was pretty much as disappointing an ECB meeting as you could reasonably ask for. A European client put it best. She notes that in addition to not doing anything to help spreads, "They created a peltro, which basically help the banks to use their balance sheet to tighten spreads. So the ECB avoids committing more of its balance sheet, and the banks use the balance sheet for carry trades rather than for lending." The criticism runs up against the fact that there are net-lending requirements for other funding facilities (TLTROs), however. And leverage ratios were just relaxed for European banks. In addition, European companies are paying down credit lines, freeing up that capital. Political considerations have kept both the fiscal and monetary response to the coronavirus from perhaps completely living up to investors' expectations. But that doesn't mean they've been grossly inadequate. It will be interesting to see if an equity market that's been able to focus on the positive developments in the U.S. case will be able to find similar silver linings to glom onto for the ECB going forward. |

Post a Comment