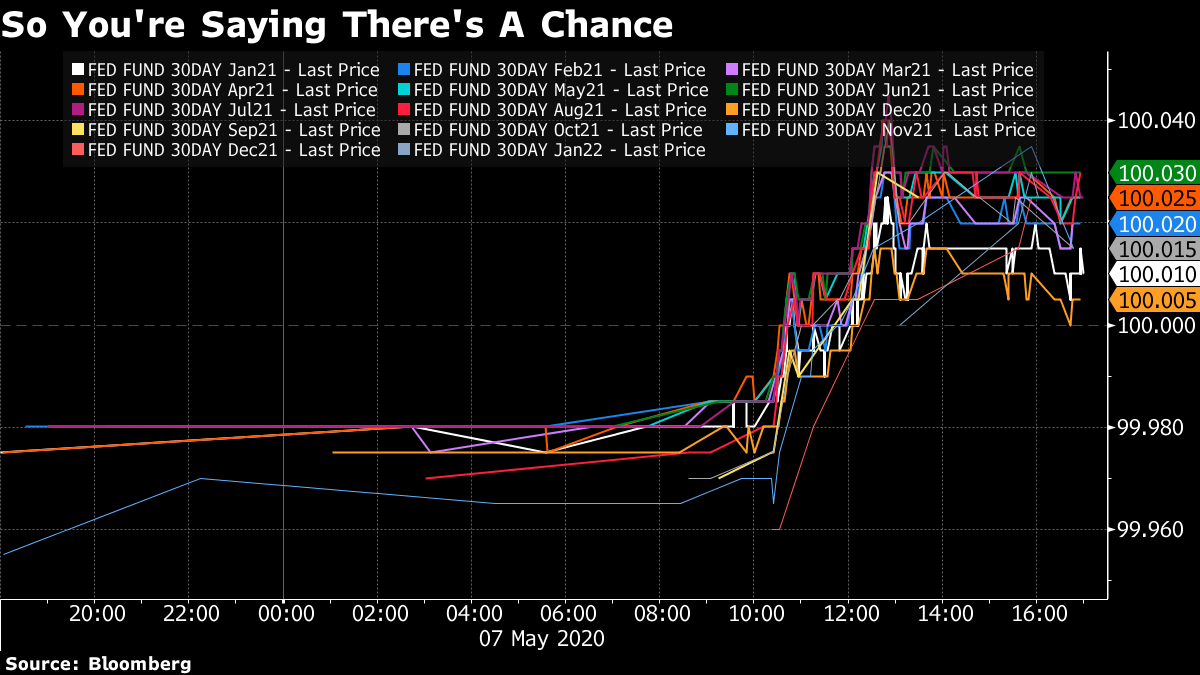

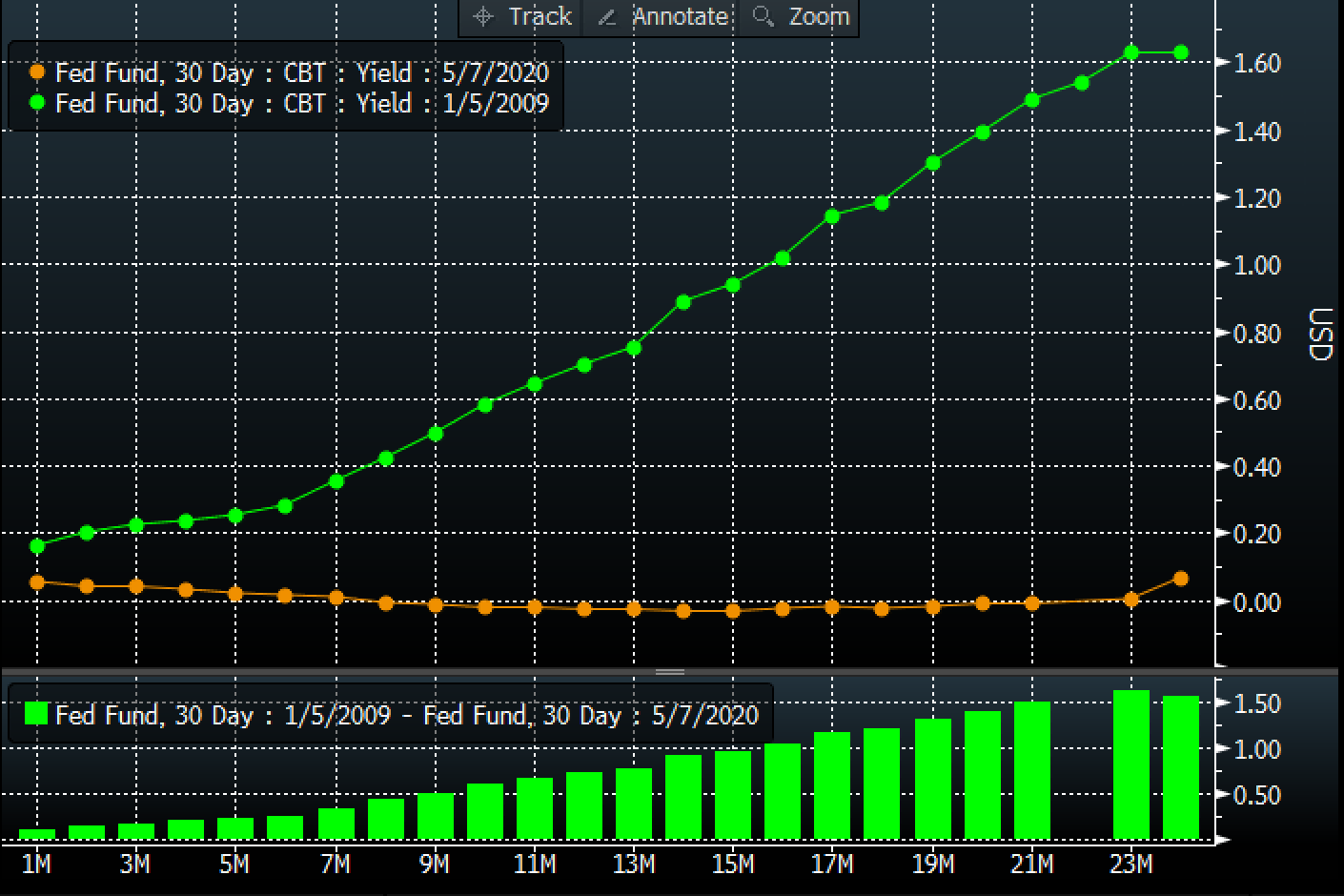

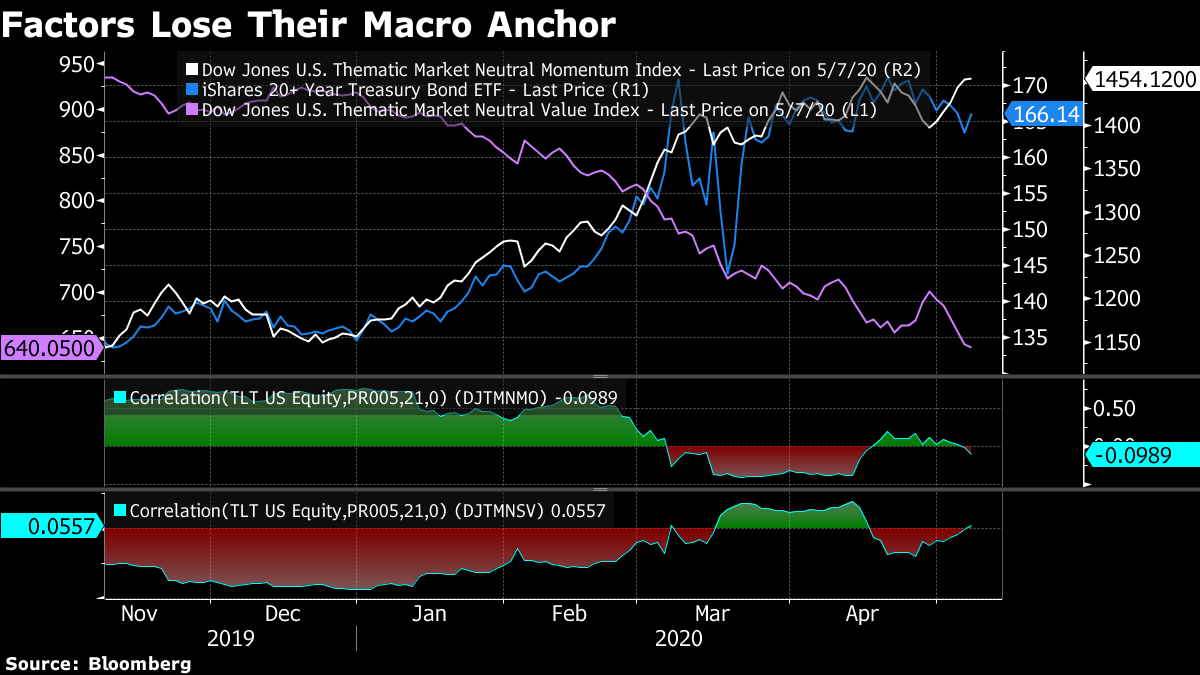

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that's amazed by how different this trip to zero rates in the United States differs from the last one. –Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter Nowhere To Go But… The asymmetries associated with a federal funds rate between 0 and 25 basis points are officially dead. No longer is it a surefire bet that the only direction American interest rates can go is up. Every fed funds futures contract from December 2020 through January 2022 closed above par on Thursday, implying a potential for fractionally negative rates during that timeframe.  Wall Street was quick to recommend fading the potential for negative rates to be adopted, however. After all, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell himself has said they wouldn't be appropriate policy in the U.S. "Markets may be undergoing a repositioning or short squeeze – akin to the recent move in oil futures (note it's easier to store money than oil) or more GSE cash is parked," writes TD Securities' Priya Misra, referring to government-sponsored enterprises (such as Fannie Mae). "Even in a more dire economic scenario, the Fed would likely favor YCC or forward guidance rather than negative rates (which affect money funds and banks)." YCC is yield-curve control, such as currently deployed in Australia and Japan. Misra is targeting the July 2021 fed funds future to rise to 8 basis points, with a stop at -10. The rates team at BMO Capital Markets seemingly agreed with the eventual outcome, but took a more cautious view on near-term pricing risks. "Over the next few weeks, we expect some investors to push the 'negative rates' trade suggesting that timing a potential bottom may be difficult absent clarifying comments from senior Fed officials," writes Ian Lyngen. "Put succinctly, given the depth of the impending recession, all policy options deserve to be on the table, and the market will need to probabilistically discount NIRP until it's crossed off the list." There's solid evidence behind this view. Powell in his most recent press conference said that the Fed was at its effective lower bound multiple times. And in general, central banks have been running away from negative rates lately. The Bank of Canada declared 25 basis points to be its effective lower bound despite a longstanding understanding since 2015 that -0.5 percent was the lowest its policy rate could go. The European Central Bank and Bank of Japan have refrained from taking rates deeper into negative territory during this downturn, to boot. On the other hand, there's nothing from the past six weeks that proves past precedent is any reliable guide to central bank actions. In the case of the Fed, as Misra notes, other unconventional options than negative rates would likely be preferred. But just because negative rates seem very unlikely to be enacted stateside doesn't mean they can't – or shouldn't – be priced. To be sure, there are both technical and quasi-fundamental reasons why so many fed funds futures traded above par. Investors betting on a widening of the gap between short and longer-term interest rates would also tend to take a long position in short-term federal funds futures – and those having to close out soured curve-flattening bets would also generate buying pressure in the front end. (As an aside, in case you're curious as to why investors would choose to put on flattening or steepening trades rather than take an outright long or short position on longer-term yields, given the likelihood that short rates stay unchanged, the answer lies in the margin requirements, at least in the case of futures. The margin requirement for a spread trade is lower than that for just one leg of the trade.) Forced closures of flattener trades as a follow-on to Wednesday's steepening (sparked by Treasury's giant issuance plan) may have exacerbated the move. Dealer positioning has been reported as short the front end in both Eurodollar and fed funds futures, as part of Libor normalization trades, along with protection sought in leveraged loans, and punts on an IOER hike coming under pressure also point in the same direction. And options bets on a fed funds rate below zero could also spur mechanical buying from dealers, as well. To be fair, that last factor isn't totally technical: for any price-insensitive delta-hedging demand from dealers to take place, there had to be some interest in punts on a sub-zero fed funds rate to begin with. So at the very least, this dynamic is yet another indication of how different this experience of the zero-lower bound is fundamentally different from the previous one. In early 2009, prior to the end of the recession or equity-market bottom, the federal funds futures curve was solidly upward sloping, predicting an escape from the zero lower bound before the year was out.  Bloomberg Bloomberg The lessons learned from the past decade – the limited ability of Fed officials to increase interest rates without causing economic and financial angst coupled with the inability of European or Japanese economies to withstand any hikes at all – now has market pricing calling into question whether the zero lower bound will even hold in America. Moreover, markets have internalized that the relationship between the growth in a central bank's balance sheet and the rate of inflation is not something to set your watch to, for that matter. Bonds Not a Factor By now, it's getting old hat to point out the mixed messages being sent by the stock and Treasury markets. A layer deeper than this is how little the bond market has to do with dividing the equity market's relative winners and losers. Some context is useful: during the fourth quarter of 2019, nascent signs of a bottoming in global activity got investors excited about a more broad-based rally in the equity market. At that time, the behavior of "momentum" and "value" factors in the equity market was relatively predictable. Momentum was and is associated with secular growth and defensive reliability, a relative beneficiary of economic angst and lower yields. Value relates to smaller, more cyclical stocks that would stand to gain from a rising tide strong enough to lift all boast. But over the past month and more, the strength of the positive/negative correlation between TLT cthe long-term Treasury ETF – and the momentum and value factors has been functionally useless.  Look no further than Thursday's price action. It's bonkers that the day in which negative rates became priced in stateside coincided with the KBW Bank Index closing up 2%. Simply, it's more difficult to expect the bond market to have a heavy hand in equity-factor performance when it hasn't really been sending any message of its own. Since April 15th, the 10-year yield has traded in a 20 basis point range of 74 to 54 basis points. And even after Thursday's 6 basis point decline the biggest since this range was established, that asset remains unique among stocks, corporate debt, currencies, or oil in having one-month implied volatility below its one-year average.  What's more puzzling is the relative disconnect between different segments of the equity market and the relative performance of high yield spreads relative to investment grade. Momentum is extremely highly correlated with the quality factor, while value, in turn, is correlated with (small) size. In other words, momentum is loosely associated with the type of safer, stronger balance sheet companies that investors are expecting to weather the economic downturn better than smaller, typically more leveraged, ones. We're using way too many y-axes here merely to show that the direction, if not the magnitude, of all these trades (momentum>value, strong balance sheet>weak) have tended to move in tandem in equities, if not the credit market.  Taken together, this price action may suggest the broad markets are pricing in a backdrop where the lion's share of companies survive, but few thrive. That's why the improvement of high yield (/value/small caps) shows up much more in the credit market than the equity market. On the other hand, if credit is truly the smarter money and a leading indicator, it could point to better times on a relative basis for value and small caps going forward. And of course, survivorship bias will tend to flatter some of the recent high yield performance at the index level. |

Post a Comment