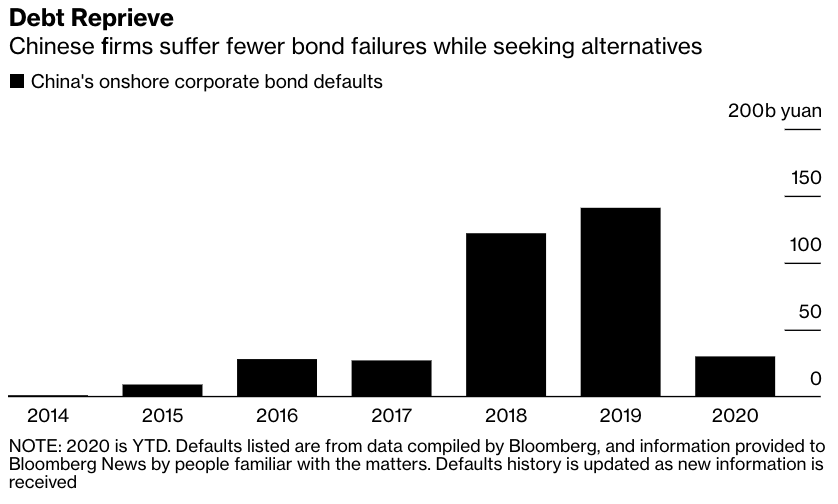

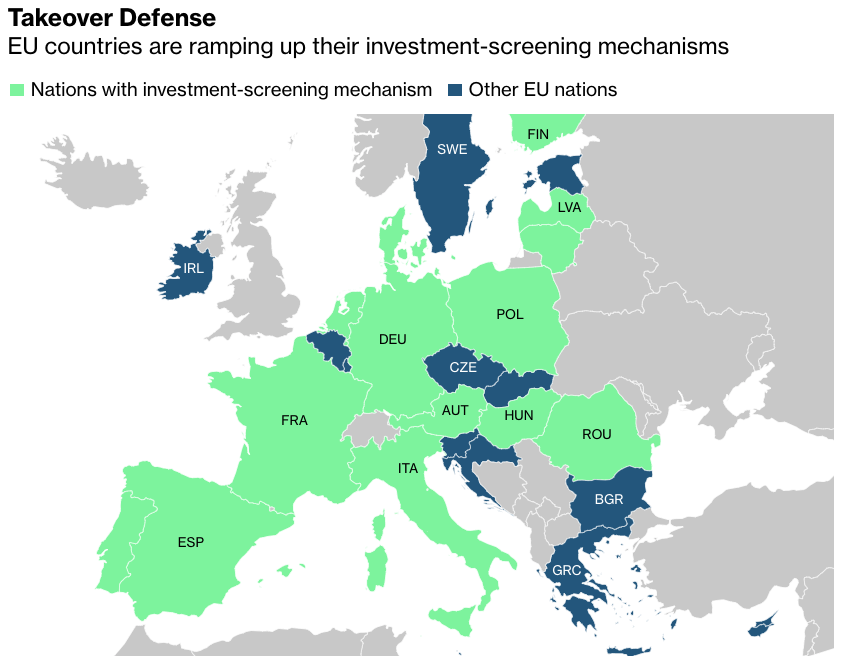

| The economic havoc wreaked by Covid-19 has had a peculiar effect on the number of Chinese companies defaulting on their debt. There's fewer of them. As of mid-April, China's bond market has recorded 19% fewer defaults than it did in the same period of last year. That's because preserving jobs has become the priority as the coronavirus continues to suppress commerce around the world, leaving little appetite to continue the deleveraging policies that contributed to two consecutive years of record defaults.  Indeed, authorities now seem to want to save as many companies as they can. Their efforts include pushing banks to keep credit flowing to smaller businesses, which are a key source of employment but also the most vulnerable in an economic downturn. They've also asked that more leeway be given to companies struggling to repay loans. There is some evidence that these measures are helping to stabilize growth. The latest data on China's manufacturing sector showed that although exporters are suffering, factories focused on domestic demand are rebounding. The danger, however, is that instead of making companies more competitive or productive, what these measures have done is to cover up their shortcomings. Even worse would be if in their rush to keep companies afloat, authorities end up creating even more zombie companies. These are entities that don't earn enough revenue to sustain themselves and instead depend on government largess to keep going. Left unchecked, they can build up ever bigger piles of debt that puts stress on the financial system and leaves less money available for more innovative companies. Another pitfall is in the banking system. China's ability to call on giant state-owned lenders to provide more financing to smaller businesses means it can mobilize support quickly. But the more aggressively banks lend, the more they are often susceptible to bad loans. Ultimately, the decision Beijing has to make is how much of the future should be mortgaged to fix the present. Financial markets are betting that it's more. With millions out of work and a very uncertain outlook, more looks like a pretty strong argument. Tense Ties Beijing's stance publicly on the U.S. election this fall has been that it doesn't want to be involved. The chances of that appear to be zero. Over the past few weeks, White House trade adviser Peter Navarro, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other Trump administration officials have ramped up their efforts to paint China as the villain of the pandemic. But it was President Donald Trump who drew the most direct link when in an interview with Reuters he described China's response to the coronavirus as being focused on a desire to see him lose the election in November. And while Beijing has already publicly denied the assertion, it does suggest that the next few months will be tense ones for the relationship.  U.S. President Donald Trump Photographer: Jim Lo Scalzo/EPA Taiwan Factor Another aspect of U.S.-China ties that got more complicated this week was Taiwan. U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar spoke by phone Monday with Taiwanese Health Minister Chen Shih-chung. What might seem commonplace was not. Though governed separately for seven decades since a civil war, Beijing has long asserted sovereignty over Taiwan, and reacted fiercely when challenged. A crucial condition underpinning formal ties between Washington and Beijing is that America not have them with Taiwan. Trump tested China's resolve on this issues in late 2016 when he spoke by phone with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen while he was still president-elected. Beijing's response was to refuse any interaction until Trump reaffirmed America's commitment to the "One-China" policy. If this week's call between Azar and Chen is prologue to another challenge, U.S.-China tensions could well rise to unprecedented levels. Getting Defensive Covid-19 has also had a notable impact on China's relationship with Europe. Diplomatically, tensions have risen as Beijing's narrative about the pandemic has sparked criticism that it's trying to use the coronavirus to champion the Chinese system of government. In the business world, concerns that Chinese and American buyers might use depressed equity prices to acquire key European companies has prompted a slew of regulations to prevent that. Berlin, Paris, Rome and Madrid have all increased their powers to veto investments from outside the European Union. The bloc meanwhile is also ushering in its first continent-wide rules for screening takeovers on security grounds. Europe's decision to ditch its longstanding open-door policy does not augur well for globalization in a post-virus world.  What We're Reading And finally, a few other things that got our attention: |

Post a Comment