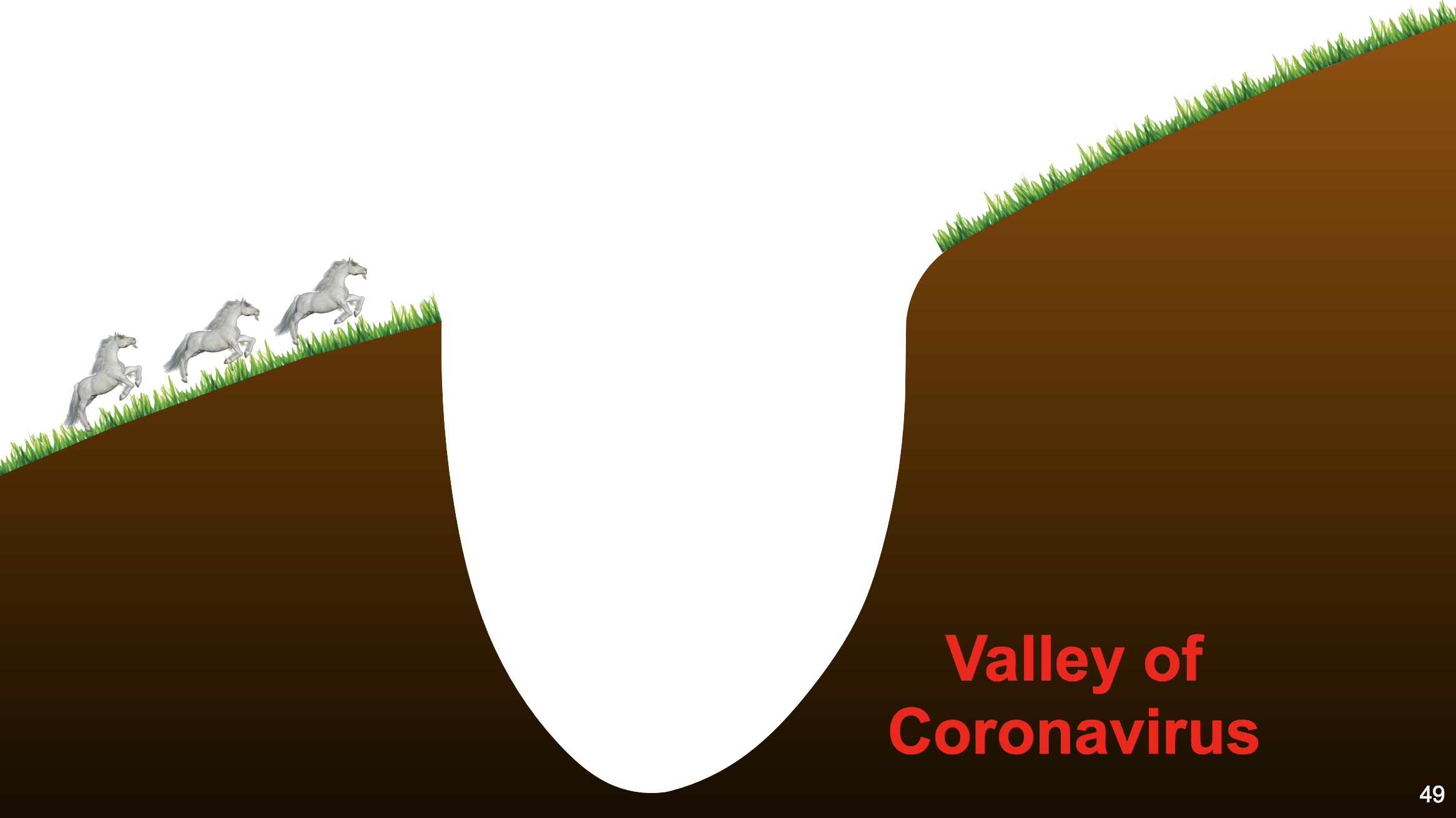

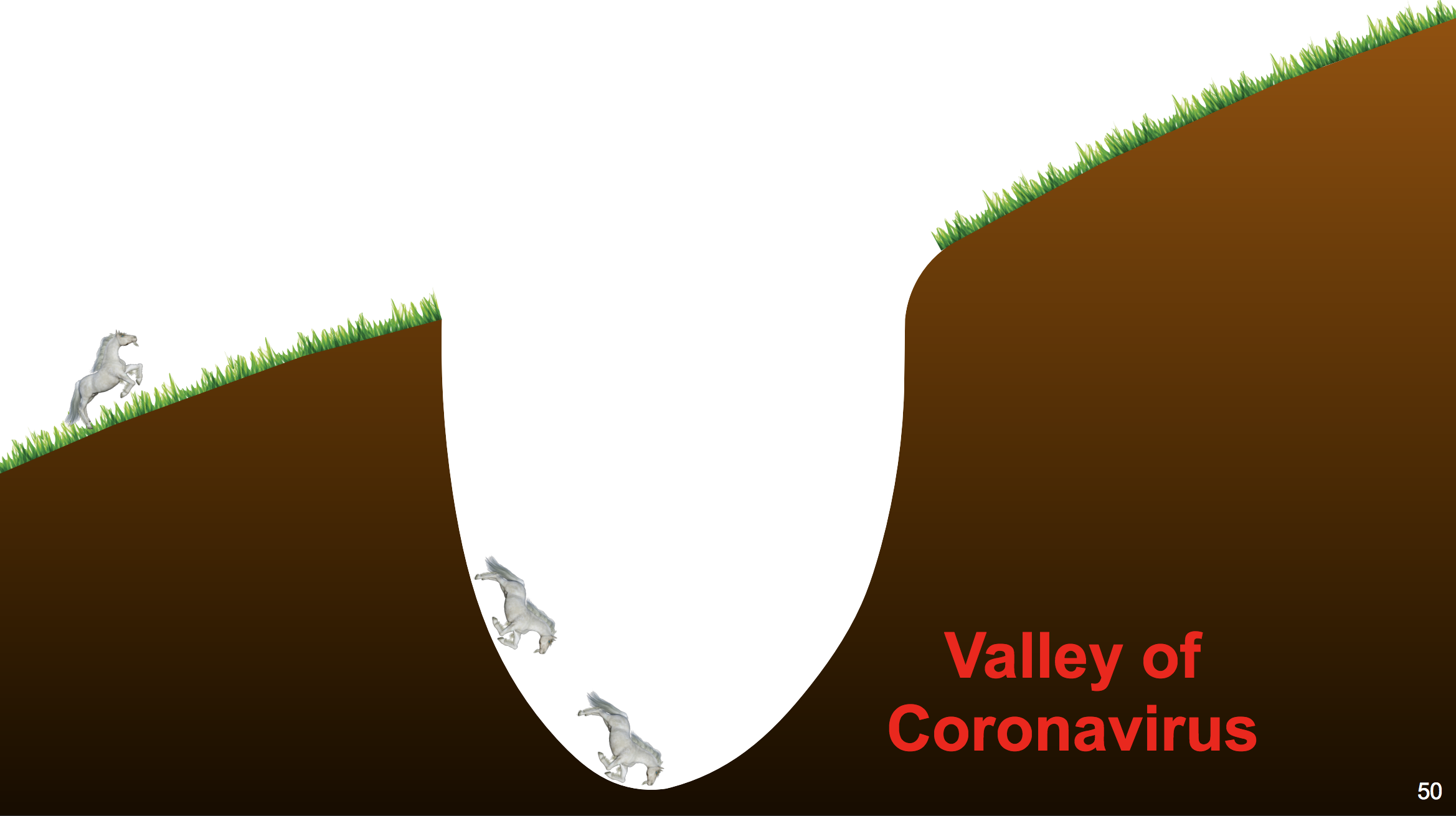

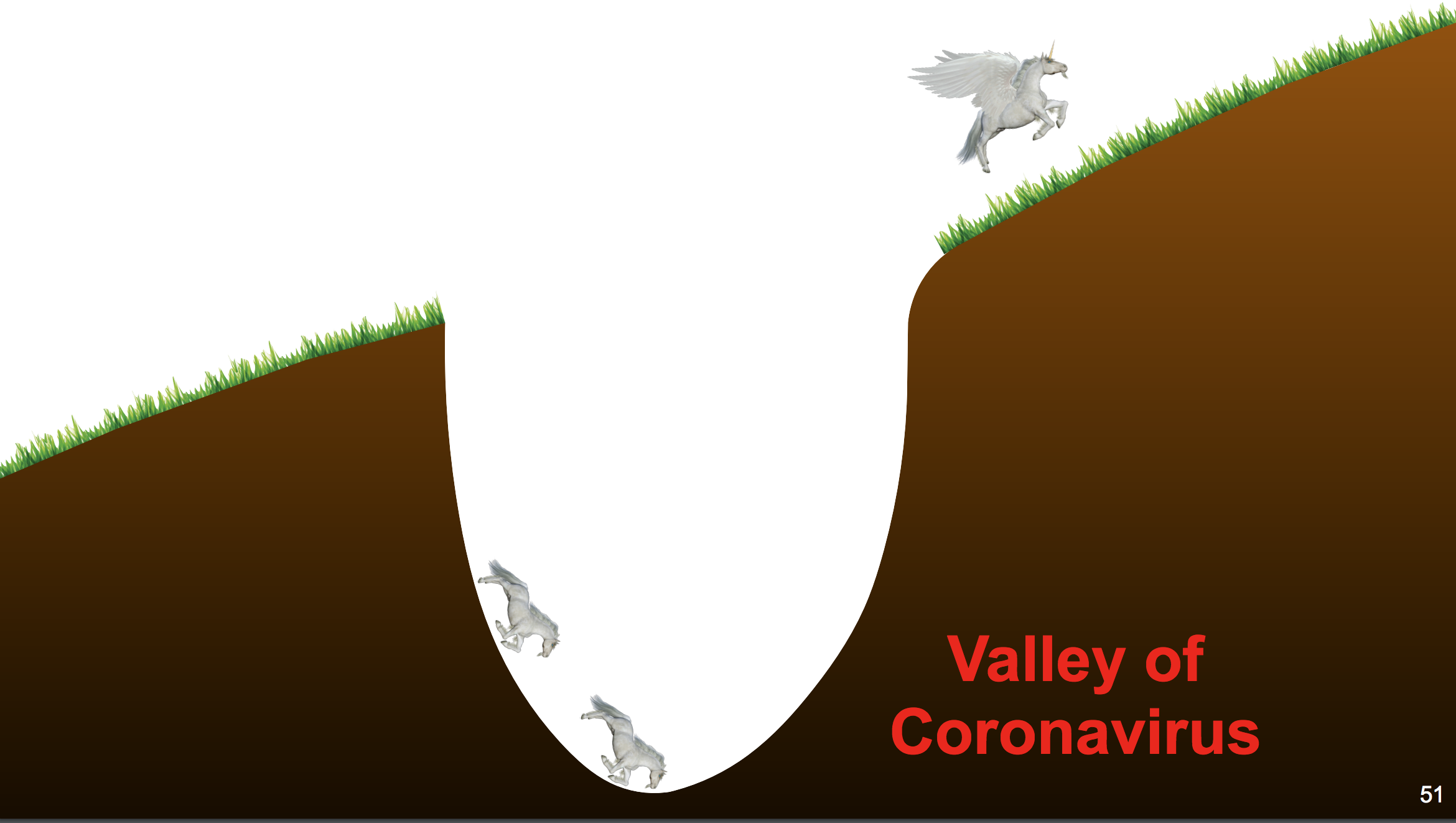

PegasusI never listen to SoftBank Group Corp.'s earnings calls, but I do tend to skim the earnings presentations for the pictures. Usually the pictures managed to capture something essential about the zeitgeist, even if you don't listen to the call; they have a purity as icons, as archetypes, even stripped from the context of SoftBank's quarterly financials. For instance I think we can all project our hopes and fears for the current economic moment onto this series of slides from today's earnings presentation:  Source: SoftBank Group Corp. Source: SoftBank Group Corp.  Source: SoftBank Group Corp. Source: SoftBank Group Corp.  Source: SoftBank Group Corp. Source: SoftBank Group Corp. I assume the horses in the ditch are actually unicorns, though only the winged horse that flew over it has a noticeable horn. I would think that you get the horn when SoftBank plows money into you at a billion-dollar valuation, and the wings when you manage to make money during a pandemic, though these are highly technical financial questions and I might be wrong on some subtleties. Here is what SoftBank apparently means: SoftBank Group Corp. said its Vision Fund business lost 1.9 trillion yen ($17.7 billion) last fiscal year after writing down the value of investments, including WeWork and Uber Technologies Inc. ... SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son's $100 billion Vision Fund went from the group's main contributor to profit a year ago to its biggest drag on earnings. Uber's disappointing public debut last May was followed by the implosion of WeWork in September and its subsequent rescue by SoftBank. Now Son is struggling with the impact of the coronavirus on the portfolio of startups weighted heavily toward the sharing economy. "The situation is exceedingly difficult," Son said at a briefing discussing the results on Monday. "Our unicorns have fallen into this sudden coronavirus ravine. But some of them will use this crisis to grow wings."

If your business model is to corral the largest possible herd of unicorns and make them run up the hill as fast as possible, a lot of them are going to fall into a ravine, that is just a basic theorem of Finance 101. Anyway who's in the ditch? The valuation of WeWork has tumbled to $2.9 billion amid the coronavirus pandemic and its ongoing business struggles, a tiny fraction of its peak when the office-sharing company was among the world's leading startups. WeWork's latest valuation was disclosed as SoftBank Group Corp., its largest shareholder, reported earnings on Monday. WeWork had been valued at $7.8 billion at the end of September after the Japanese company agreed to a bailout. Even that was far from its once-lofty $47 billion valuation.

SoftBank is currently involved in two lawsuits over its canceled tender offer to buy about a third of WeWork from its employees, investors and founder for $3 billion. If it completed that tender offer it would presumably immediately mark the stock down by about $2 billion. You can see why SoftBank does not want to do that! Because it would be paying $3 billion for stock that's worth about $1 billion, is why. Customer acquisitionHere is an amazing story from Ranjan Roy at the Margins. Roy has a friend who owns some pizza restaurants. Those restaurants don't offer delivery, but DoorDash, one of the big online food-delivery companies, will deliver their pizzas. They show up on DoorDash's website, you put in a delivery order on DoorDash, DoorDash calls in a pickup order, a DoorDash driver picks up the food and delivers it to you. This is done without the restaurant's permission or involvement, which means it's also done without the restaurant paying DoorDash a fee. (This seems to be a "demand test" in which DoorDash experiments with doing delivery for a restaurant for free, so that it can later pitch the restaurant on signing up with DoorDash and paying fees.) DoorDash will sometimes charge you less for the pizza than it pays the restaurant for that pizza, due to some combination of (1) the "MoviePass economy" startup strategy of intentionally losing money to create user growth and (2) glitches in DoorDash's web scraping algorithm. Specifically if you order a $24 specialty pizza through DoorDash, it will only charge you $16. If you like to eat specialty pizza this is a good deal for you, but it is not an arbitrage. But if you own the pizzeria: If someone could pay Doordash $16 a pizza, and Doordash would pay his restaurant $24 a pizza, then he should clearly just order pizzas himself via Doordash, all day long. You'd net a clean $8 profit per pizza [insert nerdy economics joke about there is such a thing as a free lunch]. He thought this was a stupid idea. "A business as successful a Doordash and worth billions of dollars would clearly not just give away money like this." But I pushed back that, given their recent obscene fundraise, they would weirdly enough be happy to lose that money. Some regional director would be able to show top-line revenue growth while some accounting line-item, somewhere, would not match up, but the company was already losing hundreds of millions of dollars. I imagined their systems might even be built to discourage catching these mistakes because it would detract, or at a minimum distract, from top-line revenue.

The actual nerdy economics joke there is in the second paragraph, which takes the form: Two economists are walking down the street. One of them sees a $20 bill on the ground. As she bends to pick it up, her colleague says "don't bother, if that was a real $20 bill someone would have picked it up by now." She replies, "no see this was left here by a consumer tech startup trying to maximize user growth; their Monthly Active Picker-Upper numbers are doubling every two months." She picks up the $20 bill and the startup raises money at a $2 billion valuation. The pizza arbitrage described above is basically a breakeven trade because the pizzeria has to actually make the pizzas, which costs money, but if this arb works (it does) the obvious next step is to not make the pizzas: You hand the DoorDash driver some empty boxes, he brings them to your friend's house, your friend does not complain (because this is a purely financial transaction), you capture the entire spread and can do it at scale. They basically did that too: The order was put in for another 10 pizzas. But this time, he just put in the dough with no toppings (he indicated at the time dough was essentially costless at that scale, though pandemic baking may have changed things). Now suddenly each trade would net $75 in riskless profit ⇒ $240 from Doordash minus ($160 in costs + $5 in boxes).

If you can find another pizzeria in the same boat, you can do this trade with them all night long—you buy pizzas from them, they buy pizzas from you, you pass the same empty boxes back and forth. Maybe you bring the DoorDash driver in on it; he just hangs out at the bar and pretends to deliver the pizzas, and you give him a nice tip. This is a hilarious story but there are downsides. Roy: What is it about the food delivery platform business? Restaurants are hurt. The primary labor is treated poorly. And the businesses themselves are terrible. … How did we get to a place where billions of dollars are exchanged in millions of business transactions but there are no winners? … You have insanely large pools of capital creating an incredibly inefficient money-losing business model. It's used to subsidize an untenable customer expectation. You leverage a broken workforce to minimize your genuine labor expenses. The companies unload their capital cannons on customer acquisition, while this week's Uber-Grubhub news reminds us, the only viable endgame is a promise of monopoly concentration and increased prices. But is that even viable? Third-party delivery platforms, as they've been built, just seem like the wrong model, but instead of testing, failing, and evolving, they've been subsidized into market dominance.

If restaurants and drivers complained about DoorDash but DoorDash was raking in juicy profits, you could be like "what do you want, innovate or die, the market has spoken." But in fact restaurants and drivers complain about DoorDash, and it lost $450 million in 2019 on about $1 billion of revenue. Arguably the market has spoken and said "stop it, come on, this is dumb." In the old economy of price signals, you tried to build a product that people would want, and the way you knew it worked is that people would pay you more than it cost. You were adding value to the world, and you could tell because you made money. In the new economy of user growth, you don't have to worry about making a product that people want because you can just pay them to use it, so you might end up with companies losing money to give people things that they don't want and driving out the things they do want. Meanwhile MoviePass itself is up for auction in its Chapter 7 bankruptcy, with bids due next month. Naively I would think that a pandemic would be good for MoviePass: If your business is buying movie tickets for $14 and selling them for $10 a month, months when all the movie theaters are shut down should be relatively profitable. MarketingThe way that credit ratings work is that a company that wants to issue a bond chooses one or more credit ratings agencies to rate that bond, and the company hires the agencies, and they give the bond a rating, and the company pays them. This is a fairly obvious conflict of interest: If you are a ratings agency, you will want lots of companies to hire you because that is how you get paid, so you will give them better ratings than they deserve so they will keep hiring you. This is particularly true if you are rating asset-backed securities rather than corporate bonds, since that is a market with a lot of repeat issuers who are very sensitive to ratings. You want money, the way to get money is to get issuers to hire you, the way to get issuers to hire you is to give them good ratings, so you give them good ratings. This is an extremely well-known problem, and people complain about it constantly, to the point that I sometimes defend it a little bit as being less of a conflict than people think. (Investors want high ratings too, you know.) After the 2008 financial crisis regulators and politicians talked a lot about getting rid of this conflict, and in broad strokes you would have to say that they didn't. The ratings agencies are still chosen and paid by issuers, etc.; various proposals for investor-paid ratings or random assignment of raters just never happened. Still some efforts were made to fix it, and those efforts occurred at the level of individual humans. Sure, yes, ratings agencies still get chosen and paid by issuers and so they have institutional incentives to be nice to issuers, but institutions are made up of people. If you could separate the people who do the ratings from the people who sell the ratings, maybe everything will be fine. You have a marketing division full of salespeople who go out to issuers and say "hey hire us to rate your bonds, we give everything good ratings," and you have a ratings division full of analysts who rate bonds based on their honest unbiased opinion, and you keep them separate. The analysts in the ratings division don't market the ratings, and they don't get paid based on how successful the salespeople are, and ideally they don't even talk to the salespeople. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission now has a rule (Rule 17g-5) about conflicts of interest; among other things, a credit analyst doing the rating cannot also "participate[] in sales or marketing" or be "influenced by sales or marketing considerations." This is not a fully practical division—if the salespeople never sell any ratings, the ratings analysts will have nothing to do and there'll be no money to pay them, etc.—but you can have policies and stuff and do your best. Morningstar Credit Ratings LLC did not always do its best. On Friday it agreed to pay $3.5 million to settle with the Securities and Exchange Commission over charges that its conflict-of-interests policies were not particularly strict, or particularly enforced. Part of this is just that the ratings analysts who did Morningstar's ratings of asset-backed securities also helped to sell those ratings, participating in the normal customer-relationship stuff that is the foundation of the financial industry. For instance: One example of this failure occurred in July 2015. MCR's ABS business development director was pursuing Company 1 as a potential ratings client and he wanted to attend an event held at Company 1's office so that he could continue the pursuit. The ABS business development director was unable to attend the event due to a scheduling conflict. Accordingly, the ABS business development director requested Analyst A to attend in his place, which Analyst A did. After the event, the ABS business development director emailed Analyst A: "Sorry to bother you on a weekend. . . . Did you make it over to the [Company 1] event? Was it good? Anything coming out of it for us?" Analyst A replied that he enjoyed the event and that he met the CEO of Company 1. That Monday, Analyst A followed up with an email pitch to the CEO of Company 1: "As discussed, we would love to meet you and the team to show you how we are different. We have recently rated an unsecured consumer loan backed transaction, and have a strategic focus on emerging and esoteric assets. . . . Please let us know who on your team can help us set up a brief introductory meeting." Analyst A copied the ABS business development director on his email. The ABS business development director later used that email as a prompt to further pursue Company 1 as a prospective client. According to the ABS business development director, Analyst A's communications with Company 1 were efforts at marketing MCR's ABS ratings services. In an effort to grow MCR's ABS rating business, MCR's ABS business development director instructed ABS analysts to identify and initiate contacts with potential clients (referred to as "targets"), set up marketing calls and marketing meetings with them, and offer them indications. MCR's ABS business development director also instructed ABS analysts to (i) solicit potential clients at industry conferences, (ii) repeatedly follow up with those potential clients, and (iii) encourage potential clients to attend marketing meetings with MCR. Analysts understood that the goal of their contacts was to persuade potential clients to hire MCR to rate ABS. These activities were undertaken with the knowledge of senior MCR managers.

That is the most normal boring story in the world—ooh they went to industry conferences!—except that really it's a bit unfortunate for the analyst to even talk to the business development guy, never mind the prospective client. If you send analysts out to meet prospects and "offer them indications," they are obviously not going to give the clients bad indicative ratings. ("Hire us to rate your bonds and we will rate them all CCC, here's my business card.") And once you tell a prospective client "we're great to work with and we'll give all your bonds AAA ratings" it is hard, just socially, to walk that back in the actual rating. "I thought you said you'd give us AAA ratings," the client will say, not unfairly. So you can just see the conflict of interest being created here, as the analyst tries to win business by hinting at generous ratings and then feels constrained to deliver those generous ratings. Also this seems bad: For example, an MCR ABS analyst ("Analyst B") undertook extensive efforts to recruit Company 2, an issuer in the ABS marketplace, as an MCR client. … Analyst B also offered to provide Company 2 with an indicative rating on a security issued by Company 2. After Company 2 failed to respond to this follow-up, Analyst B decided to write and publish a commentary on the credit strength of certain notes in Company 2's deals, and to follow up with Company 2 again after the publishing the commentary. The commentary mentioned Company 2 by name, was tailored to the securities that Company 2 issues, and said that, based on MCR's view of such transactions, MCR would assign higher ratings to the notes in Company 2's deals than other credit rating agencies. Analyst B sent the commentary to Company 2 on the same day that it was published.

I mean, maybe it's not bad. Perhaps this was just the analyst's deeply held personal opinion. Perhaps he believed that Company 2's bonds were better than their existing ratings, but conversely he thought Company 6's bonds were much worse. Perhaps he was also publishing unsolicited notes about Company 6 saying "these notes are terrible and we'd never rate them that high." (This happens! It is also a potential conflict of interest: You give bad unsolicited ratings to the companies that don't hire you and good solicited ones to the companies that do, etc.) Perhaps Analyst B simply had a refreshing, idiosyncratic, novel view of structured credit; he published his honest opinions, and Morningstar naturally pitched the companies he liked ("you're a good fit for us because our analyst loves your model") and not the ones he didn't. Perhaps the whole business is simply about intellectually honest differentiated analysts and sensitive marketers who are attuned to what issuers are the best fits for their analysts. But, uh, I don't know, generally if you pester a company a lot to hire you to rate their bonds, and then you put out an unsolicited note about how good their bonds are, people are going to assume that you're doing it for the money. I think my favorite part of the SEC settlement is the remedy. There's a fine, and Morningstar has to have some new policies and train its analysts about the conflict of interest rules. But also: Within 180 days of the entry of this Order, MCR will conduct a live training program addressing the Commission's conflict of interest rules, including but not limited to the prohibitions set forth in Rule 17g-5(c)(8). This training program shall educate attendees regarding applicable rules and regulations and relevant policies and procedures. This training shall also explain how employees can raise concerns and the avenues for doing so, including internally and directly with the SEC through the Whistleblower Program.

See, Morningstar won't just tell its analysts not to do any more marketing. It will also tell them: If anyone asks you to do any marketing, you can call up the SEC and tell them about it and they will give you money, through their whistle-blower program. Incentives matter! If the SEC will give the ratings analysts a bigger bonus for refusing to market ratings than Morningstar will give them for doing the marketing, then the marketing will stop. AdvertisingIf you see a company's advertisement on television, does that make you want to buy its stock? Just an ad for its product, I mean, an ad for Ford trucks or Budweiser beer or Citigroup financial services or whatever. After seeing a really inspirational beer ad, do you wander over to your computer, pull up the SEC's Edgar system, and read the beer company's 10-K to consider an investment? I … do not. This is not a thing, for me. I mostly don't buy the beer either, though, or at least I like to think that I am relatively unswayed by advertising. And yet advertising works and is a kajillion-dollar business, and surely there is some overlap between the messages "our beer is good, buy it" and "we are a good beer company, buy our stock." Why shouldn't the beer ad also make you buy the beer stock? Here are a blog post and related paper by Jura Liaukonyte and Alminas Zaldokas on television advertising and retail investing: We find that, within 15 minutes of seeing an ad for a firm's product or service, investors begin searching for financial information on that firm's stock. This surge of attention leads to a higher trading volume of the advertiser's stock the following day – and contributes to a temporary rise in the stock price of that firm. Indeed, our recent research shows that the effects of advertising on investor behavior and stock prices are more far reaching than previously believed. We documented these effects by comparing responses among households that were and were not exposed to the ads. We took advantage of the three-hour lag between the East and West Coast for airing the same commercials during the same shows on national television channels. … Within 15 minutes, an average TV ad spurred an immediate 3 percent increase in queries of the Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval (EDGAR) system of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Google searches for related financial information immediately climbed by 8 percent. We found that each dollar spent on advertising translated to roughly 40 cents of additional trading volume in the advertiser's stock. The effects were most pronounced for trades initiated by retail investors. Overnight stock returns were positive – though they partially reversed during subsequent trading days.

Honestly that Edgar statistic is blowing my mind a little. There is a chart in the back of the paper showing an example, a Citigroup Inc. ad that aired on March 3, 2017. In the 15 minutes before the ad aired, there were a handful of Edgar searches for Citigroup; in the 15 minutes after the ad, there were hundreds. Of Edgar searches! Edgar! Hundreds of people saw an ad for a bank and decided to go read its 10-K on the SEC's website. (To be fair, this is bank-specific; "commercials aired during primetime hours and involving the financial sector sparked the strongest investor response.") It makes me feel better about the world, somehow; there are hundreds of people out there whose television ad viewing is not resigned passive consumption but rather a source of inspiration for further detailed research. By the way, I said "Budweiser beer" above, but of course Budweiser is not a company. It is one of many brands of beer behemoth Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV. If you saw a Bud Light ad, would you go buy AB InBev stock? Maybe; the ticker for AB InBev's American depositary receipt is BUD, so a casual Robinhood search might work. But in general, write Liaukonyte and Zaldokas, "Products with names that matched or shared similarities with the name of the company itself spurred greater reaction." You're not going to do too much research, from your television ads. Things happenFour functions of markets. The Fed's $600 Billion Challenge: Lending Directly to Businesses. J.C. Penney Faces Possible Snag to a Smooth Restructuring. J.C. Penney Needs Quick Bankruptcy Exit to Avoid 'Disastrous' Result. Behind Royal Caribbean's Lifeline, a Shrewd Bond Market Maneuver. What Happens When a Lender's Borrowers All Lose Their Jobs at Once? SoftBank in Talks to Sell T-Mobile Shares to Deutsche Telekom. Big Consulting Firms Push Back Start Dates for New Hires. Should the Modern Corporation Maximize Shareholder Value? Harvard's Reinhart and Rogoff Say This Time Really Is Different. Purell's Claim to Combat Disease Spurs Demand — and Lawsuits. Martin Shkreli's Bid for Early Release From Prison Rejected. Man who tokenized himself on Ethereum becomes AI deepfake. "South Korean soccer club FC Seoul apologized, expressing 'sincere remorse,' after it was accused of placing sex dolls in empty seats during a match." If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! |

Post a Comment