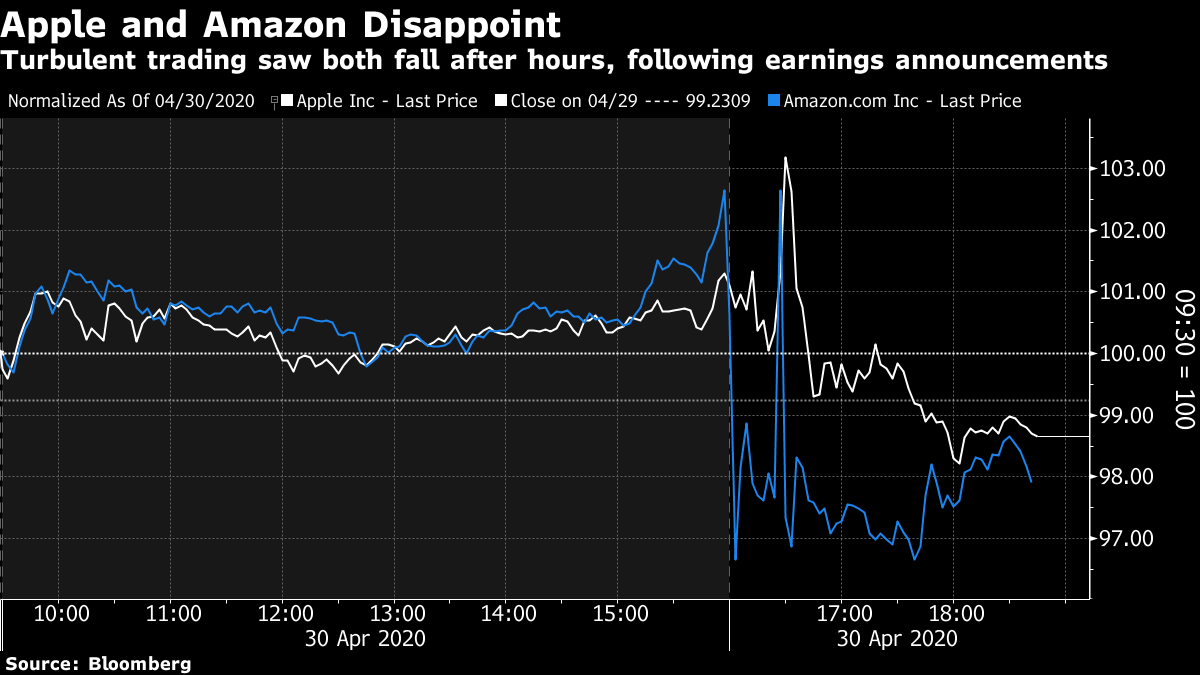

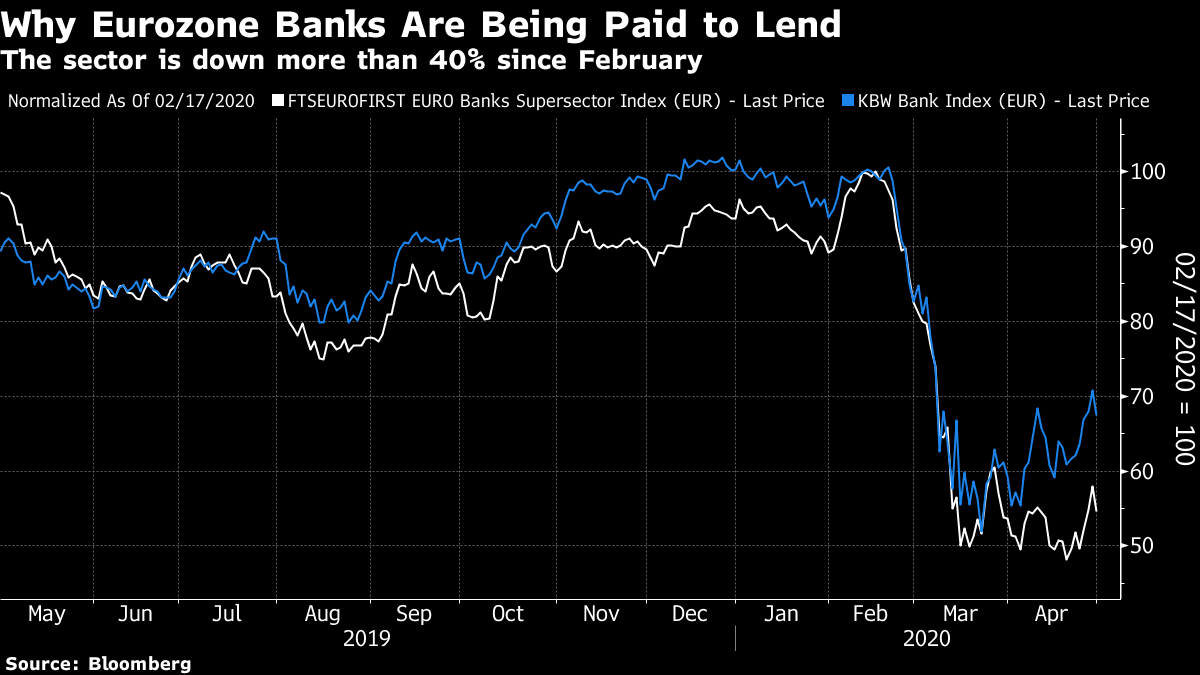

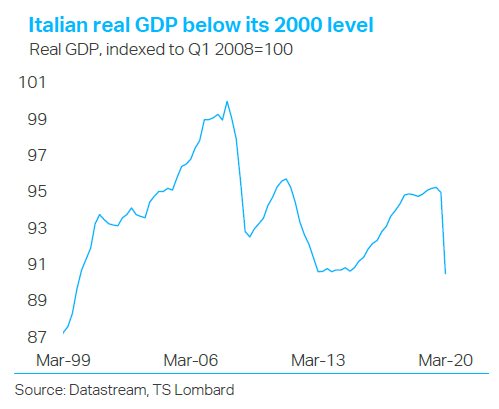

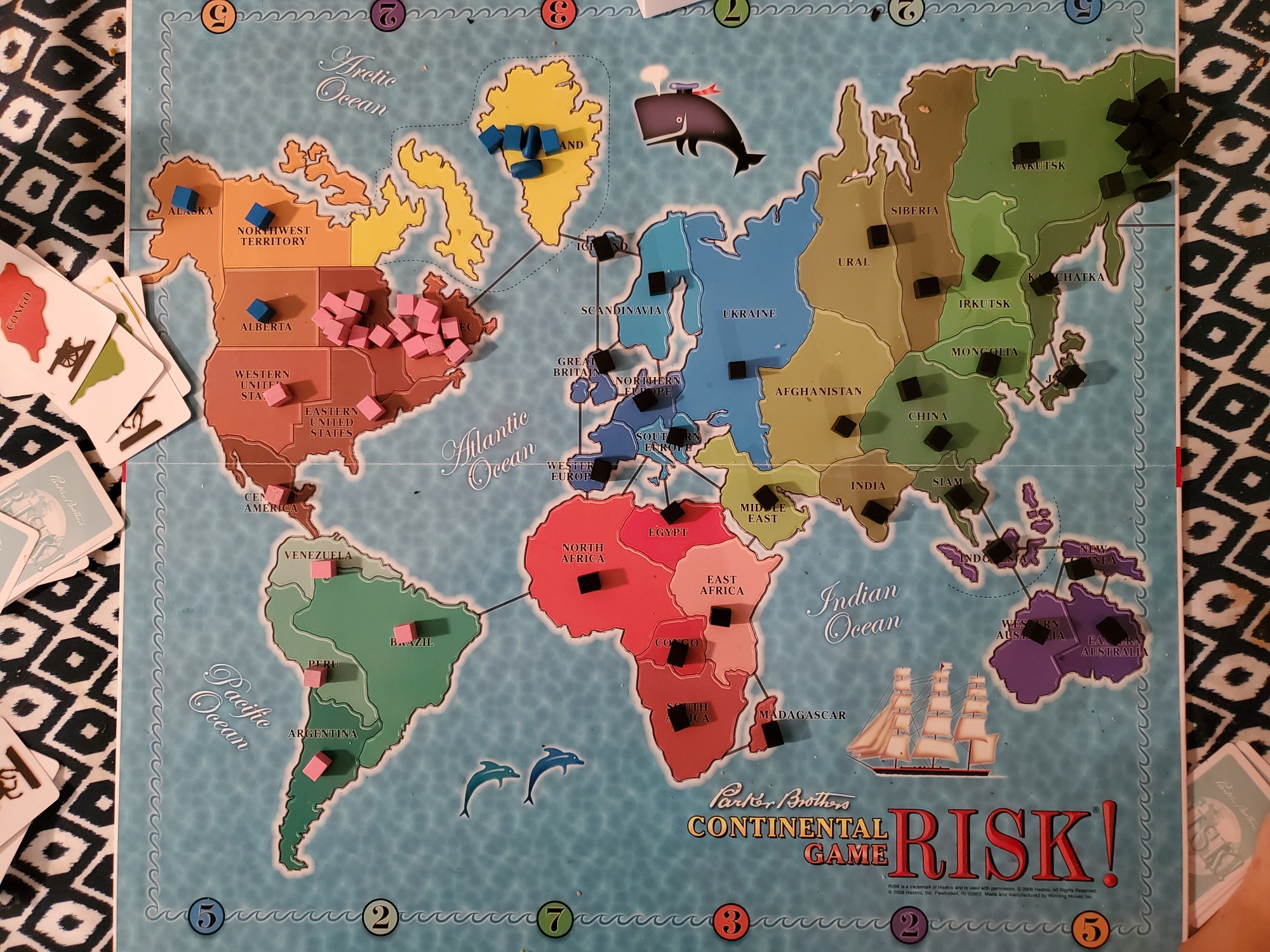

Woke Up This Morning ... Tony scares us even more than Jay does. Both of them matter more than the Don. But everyone is most scared of the Mob. This has nothing to do with the Sopranos. Rather, it is about the relative market-moving ability of Dr. Anthony Fauci, America's chief fighter of infectious diseases, and Jerome Powell, who runs the Federal Reserve. Both matter more than President Donald Trump, for now. But dig deeper and it becomes clear that what really matters to the world's financial movers and shakers is the great mob of voters out there in the real world, and how they might respond to whatever measures they take to deal with the pandemic and the economic crisis that has come in its wake. That, in turn, might owe a lot to the Don. Any word from a man who is a genuine expert on epidemics with access to real knowledge has the potential to resonate. On Wednesday, stocks took a jump forward globally on reports that the latest research project on Gilead Sciences Inc.'s drug remdesivir was seeming to have a positive effect in shortening recovery times from Covid-19. The research is still preliminary and not peer-reviewed, but the excitement intensified after Fauci was interviewed on Wednesday at lunchtime, making clear that the findings were significant because they showed that it was possible for a drug to block the virus's progress. Gilead's share price had been bumping along for months before the Covid crisis took hold. As the chart shows, it then took off in March, as the market fell. Pharmaceutical companies were seen as great defensive stocks. Now, the two seem to be going hand in hand. If remdesivir really does work and can be mass produced quickly, then that should be great for Gilead's profits and also — rather more importantly — for global public health, and the global economy.  It was noticeable that the excitement over Fauci and Gilead swamped Wednesday's meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, at which admittedly close to nothing happened. Powell gave an economic assessment so downbeat that some traders are now expecting rates to stay as low as they are now into 2024. But he held off on announcing significant new programs as well, reflecting a desire to make sure the Fed can chew what it has already bitten off — in the form of a raft of new supports for markets and lending — before trying to digest anything more. That emphasis was wise. The evidence so far is that the Fed's programs, and those of the Treasury,have been chaotic, and — much more damaging politically — appear to have gone to big guys, not little guys. The optics are not good when headlines reveal that scarcely impoverished institutions such as Harvard University and the Los Angeles Lakers have received public handouts while small businesses have been unable to get their hands on any money before it runs out. After the mistakes made in the wake of the last financial crisis, Powell rightly grasps that it is very important to get it right this time — or face what might be a dangerous populist backlash. Or, in our Sopranos analogy, the Mob. Note also in the chart that the S&P 500 is almost exactly where it was 12 months ago. This is surely extraordinary given that the economy has just sustained its biggest peacetime hit in history. The dichotomy between a reeling Main Street and a dancing Wall Street looks terrible, and many Wall Streeters are pointing this out. That fear also helps to explain the strange goings-on in after-hours trading of two titans of the age, Amazon.com Inc. and Apple Inc., following their post-market earnings announcements on Thursday. Amazon has widely been seen as one of the few clear winners from the Covid lockdown, as people have been forced to move to online deliveries — but its CEO Jeff Bezos went out of his way to say that the costs associated with the lockdown would eliminate all profit during the second quarter. There is discontent that Amazon, or anyone else, might take advantage of the pandemic, while problems with safety for its staff have generated a lot of bad publicity. Bezos probably correctly calculated that it is necessary to put himself on the side of the angels and avoid a negative backlash — but doing this did not please the market. Meanwhile, Apple had the financial wherewithal to announce a huge stock buyback and managed to notch results that were better than some had expected. But the virus matters more. The fact that the company also felt the need to discontinue earnings guidance, because of the scale of the uncertainty that the pandemic is generating, helped ensure that Apple's stock, like Amazon's, fell after hours:  There were more signs of attempts to calculate and preempt public opinion in the day's big event in Europe. The European Central Bank announced that it is now effectively paying banks to lend to people, and doing so on ever more generous terms. This is a reasonable response to the horror show that has been euro zone banking since the virus reached European shores. Shares of the region's banks have tumbled more than their counterparts in the U.S.:  But the ECB didn't take a number of other measures that appear necessary, such as stepping up its program of quantitative easing, while Christine Lagarde, its president, pointedly called on the region's elected politicians to do something. The ECB lacks the political legitimacy to take the measures that look necessary to salvage Europe's weakest economies. That must come from governments themselves, and realistically this will involve other nations supporting those that are worst hit. Italy already had a slumping economy even before it became the first country in Europe to feel the full force of the coronavirus. As TS Lombard of London points out, in real terms its GDP is lower than it was 20 years ago:  There is a good case to be made that it is in the interests of French and German citizens to help Italy get off its knees. But it requires a good politician to make such a case, and it also requires intense pressure. This probably explains why Lagarde and the ECB are trying to use what leverage they can to prompt Europe's politicians to respond with some measure of common fiscal policy. So the virus matters more than central banks, in the eyes of the market, while CEOs and central bankers alike are increasingly looking ahead to the risks that a botched response — in either medical or economic terms — could prompt social upheaval. On that score, perhaps the Don does matter. Only about four months ago, the greatest preoccupation for investors the world over was the poor state of U.S.-Chinese ties. The hope was that this year they could begin to patch together a better trade relationship. Now, with ever louder talk of an attempt to extract reparations from China for its role in birthing the virus, and with the president facing reelection in six months, we could be about to see a further serious deterioration in that relationship. There may yet be some more Sopranos analogies in our future, and we really do not want them to apply to the relationship between the U.S and China. Survival Tips: Risk! Management Board games have made a comeback during the lockdown, and as far as my family is concerned the best by far is Risk. For the uninitiated, the object is world domination, and it can go on for many hours. Unlike Monopoly — which is interminable and gets more boring as the game progresses — the tension and the strategy only get more exciting as time goes by. I invested in a retro re-edition of the gameas first released in the U.S. by Parker Brothers in 1959. It looks old-fashioned. There is a jaunty sperm whale in the Arctic Ocean and a couple of gamboling dolphins in the South Atlantic; it is drawn using Mercator's projection, so Greenland looks bigger than Australia; and its division of the world into territories looks eccentric, with China counting for exactly as much as Yakutsk, or Western Australia, or Iceland. This is the board as it appeared when we ended our last game:  I was playing with black pieces and had taken control of Australasia, Africa, Europe and — critically — Asia. My kids are already crying foul over my shoulder that I am highlighting the one game we have played so far that I have won. There are important lessons to be learned, however, and had we played much longer I would have suffered a downfall. I had taken Asia, but at great cost and had massed all my spare armies in Kamchatka to deter a possible future invasion from Alaska. Meanwhile, my children Josie and Jamie had cemented a firm and impregnable Alliance of the Americas, and were poised to make a pincer movement, dislodging me from Iceland and North Africa and opening the way to invade the rest of Europe and Africa. The strategic lessons for the real world are, first, that it is very hard to get anywhere without making an alliance and sticking with it for a long time; and second, that attempting to take on Asia is a fatal temptation. It is simply too big and diverse to take on. If you do manage somehow to take control of Asia, it is impossible to hold on to it for long. My kids were about to do very well by sitting back in the Americas, building a lot of armed forces, and then turning their attention eastward to Europe and Africa. These lessons remain very valid. And yet some leaders still do not seem to grasp that it is important to make alliances, and to avoid the temptation to try to take on Asia. My advice to investors is that there is a need for greater risk (or Risk!) management. If world leaders cannot master the simple strategic lessons you can get from playing a board game with your kids, the world is a risky place indeed. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment