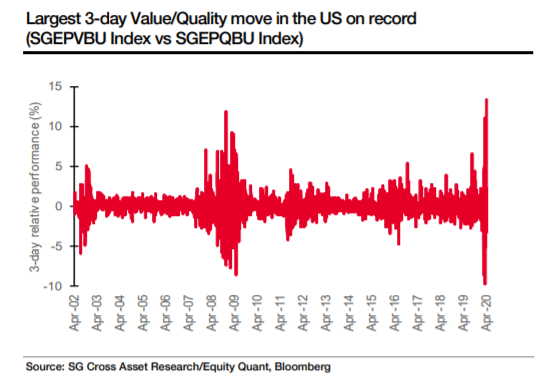

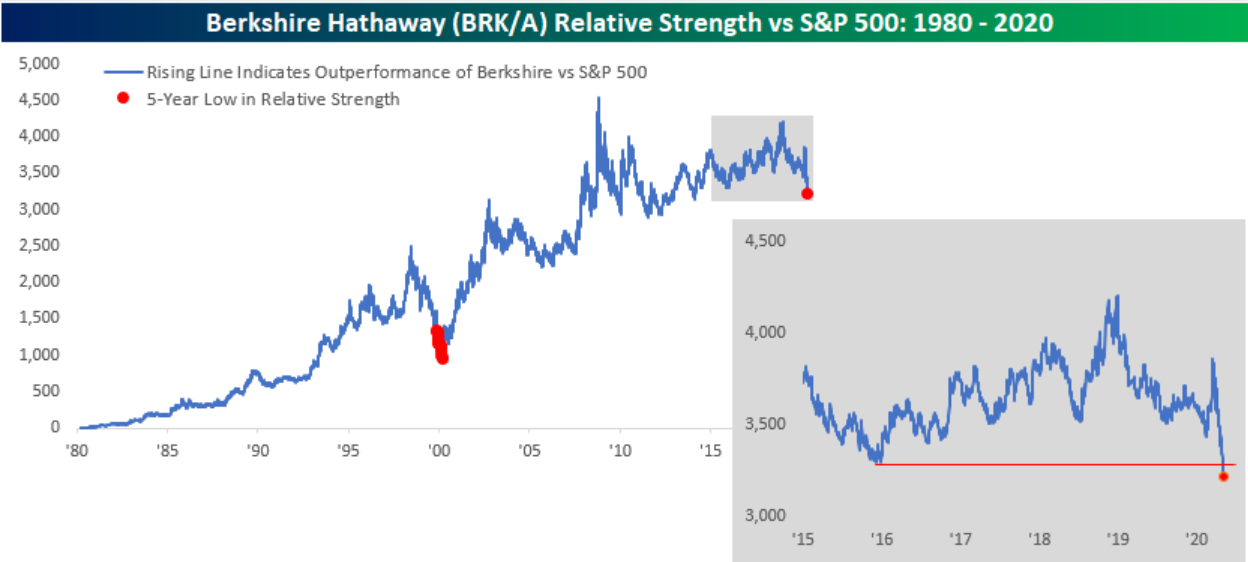

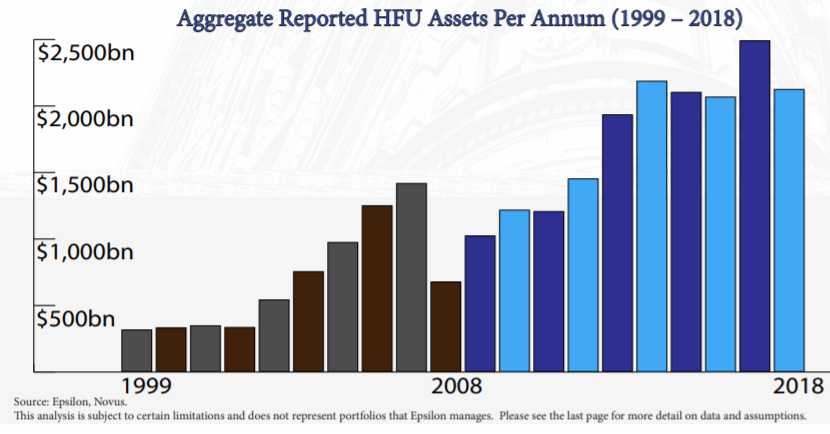

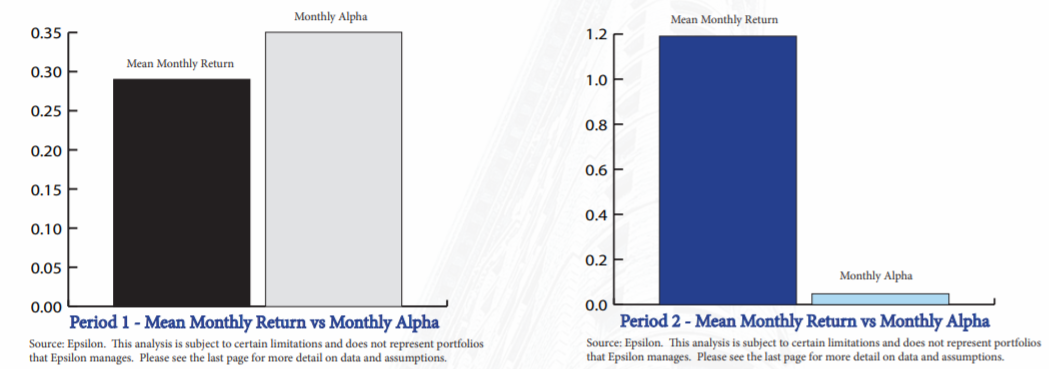

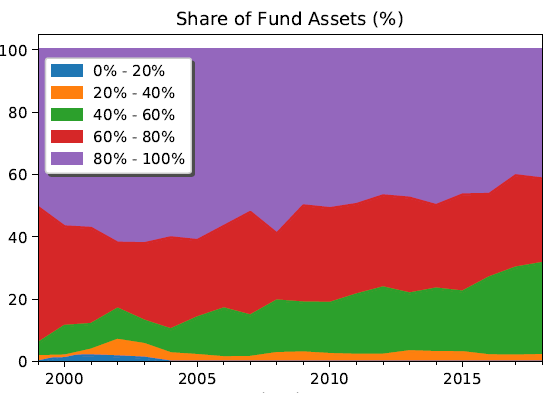

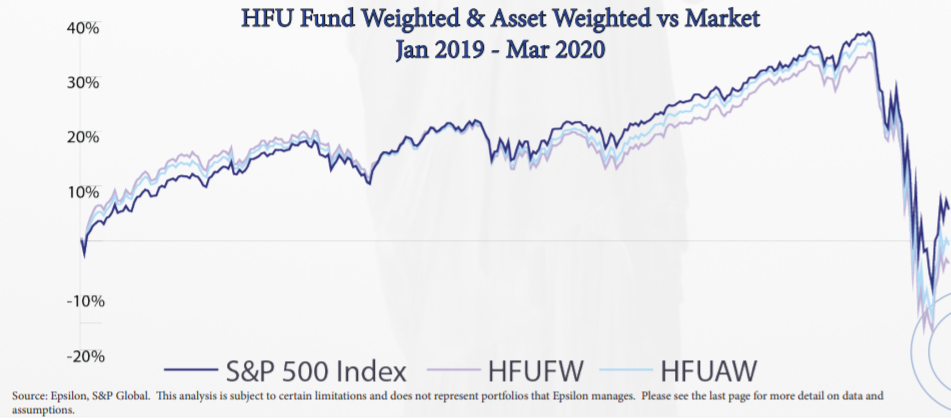

A Brutal Market to Beat This decade is only four months old, but it's already a terrible one for anyone trying to beat the market. The following chart shows the performance of the S&P 500 in its usual market cap-weighted form relative to the equal-weighted version, in which each constituent accounts for 0.2% of the index. When the line is sloping downward, it means the overall index is doing worse than the average stock, creating a decent chance to beat the market just by dumb luck. When it goes upward, the index is doing better than the average stock (which means in practice that big companies are dominating). The 2010s were a tough decade for stockpickers. But look what has befallen them this year:  This looks extreme, because it is. In such an environment, stocks are primed for bizarre turnarounds, but timing them is close to impossible. The following chart, from Andrew Lapthorne, chief quantitative strategist at SG Cross Asset Research, shows that value stocks (which look cheap compared to their fundamentals) have just had their best three-day run compared to quality companies (with strong balance sheets) since records began nearly 20 years ago. That only happened because value had previously sold off viciously while investors piled into the stocks least likely to go bust:  The biggest culprits are, regular readers won't be surprised to hear, the FAANGs, now increasingly also referred to as the FAMAGs (for Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Microsoft Corp., Apple Inc. and Google's parent Alphabet Inc.). The dominance of the big internet stocks came into play again Monday, as the S&P 500 ended the day in positive territory. The number of declining stocks almost exactly equaled the number of gainers. It was the weight of the FAMAGs that made the difference. This is a long-running secular trend, but it has moved into a new gear in the last seven months or so. The chart below starts when the market topped in January 2018 before suffering the first of two brutal corrections. From there until last autumn, the S&P 500 failed to make any significant progress, and the NYSE Fang+ index didn't outpace world stocks as a whole. Since then the S&P has gone on a tear, tanked, and staged a V-shaped recovery. And the Fangs have outperformed it virtually every step of the way:  To ram home just how difficult this makes life for stockpickers, we heard over the weekend from Warren Buffett, CEO of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., and by some margin the world's most famous equity investor. Giving a virtual version of his annual investor conference from Omaha, Nebraska, he admitted that he couldn't find appealing opportunities at present. His cash pile has grown thanks to the decision to get out of airline stocks. And while he was receiving (relatively unattractive) offers to buy or support companies at the beginning of the crisis, they soon dried up. That might have been because the Federal Reserve came to the rescue so swiftly, denying Buffett the chance to be the savior (on good terms for Berkshire Hathaway) himself. Monday's market reaction was very negative. The idea that a crisis had hit the markets and yet the Sage of Omaha had found no way to take advantage was shocking for many. As these charts from Bespoke Investment Group show, this was Berkshire's worst run of relative strength compared to the S&P 500 in 20 years, since the internet bubble was about to burst.  That proved to be a great time to buy Berkshire stock. This time is trickier. The market only looks as good as it does because of the internet giants, and Buffett surely cannot pile in at these levels. But if he really finds nothing else appealing at current valuations, it implies that the Fed will have to let the market fall a long way before Berkshire can start to deliver. Buffett has some problems, in that he has become virtually a one-man signaling machine. The fact that he abandoned his normal breezy demeanor helped depress the market (before the FANGs, currently even more powerful than he is, turned things around). Whether he wants it or not he has a certain responsibility these days. But for the most part his incentives are fairly straightforward — he deploys Berkshire's cash if he's confident he can generate a great return, and otherwise he leaves it where it is. Before Berkshire, he was a pioneer managing investment vehicles that would come to be known as hedge funds. And this market is really giving them fits. Research published Monday by Epsilon Asset Management's Faryan Amir-Ghassemi and Michael Perlow, and New York University's Andrew Papanicolaou lays bare the problem. Hedge fund managers want to attract funds, and to produce the over-market returns that trigger their performance fees. Over the last decade, they succeeded greatly in the former, and failed miserably in the latter. These things are almost certainly related. This chart shows the total funds managed by the equity hedge fund universe, as examined by the team at Epsilon:  In the decade starting in 1999, the hedge fund industry was still more or less composed of opportunistic vehicles of the kind Buffett used to manage in the 1960s. Over the following decade, they morphed into something bigger, more institutional, and ultimately slower and clumsier. This is what happened to equity hedge funds' alpha (or ability to deliver returns over and above the market):  Note that these returns are before hedge funds' exorbitant fees. So the offer is (very) ordinary performance for extraordinary fees. Part of the problem is that as funds have grown bigger, so they have tended to hold larger stocks, and tended to move closer to the overall index. The following chart measures funds by their "active share," or the proportion of the portfolio that is different from a direct holding of their benchmark index (so a well-run index fund would have a 0 active share, and a concentrated portfolio of micro-caps not included in the index would have an active share of 100). Hedge fund managers are much more truly active than mutual funds, but they have steadily grown less active as time goes by.  This leads them to a horrible dilemma. There is an old market cliche that nobody ever got fired for holding IBM. But no hedge fund is ever going to be hired for holding FAANG stocks. Exposure to such companies can be bought far more cheaply in an index fund. If a fund manager truly believes in Microsoft, for example, there is really no point on acting it unless he or she is prepared to make a huge bet, putting 10% or more into one stock. But against that institutional incentive to avoid the FAANGs is the cold fact that the best way to make money this year has been to hold them. This has at least led to one interesting reversal of fortune. The following chart shows Epsilon's index for equity hedge funds weighted by volume of assets (HFUAW) and by funds (HFUFW). The first can be viewed as an equivalent to the cap-weighted S&P 500 and the latter to the equal-weighted S&P 500. The same thing is happening to hedge funds as to the market as a whole. Usually the smaller, nimbler ones do a bit better. At present, the big ones are outperforming (although they are still failing to beat the S&P 500). This may be because they are doing a better job of guarding against downside in a sell-off.  Alternatively, it is because the big hedge funds have more money salted away in the FAANGs. Either way, everyone agrees this is an impossibly difficult market. To Warren Buffett and the hedge fund industry, add Goldman Sachs Group Inc.'s David Kostin. The investment bank's chief U.S. equity strategist drew up the dilemma in stark terms this weekend: the five largest companies collectively account for 20% of S&P 500 market cap, the highest concentration in more than 30 years. Although the index trades just 14% below its all-time high, the median S&P 500 constituent still trades 23% below its record high…

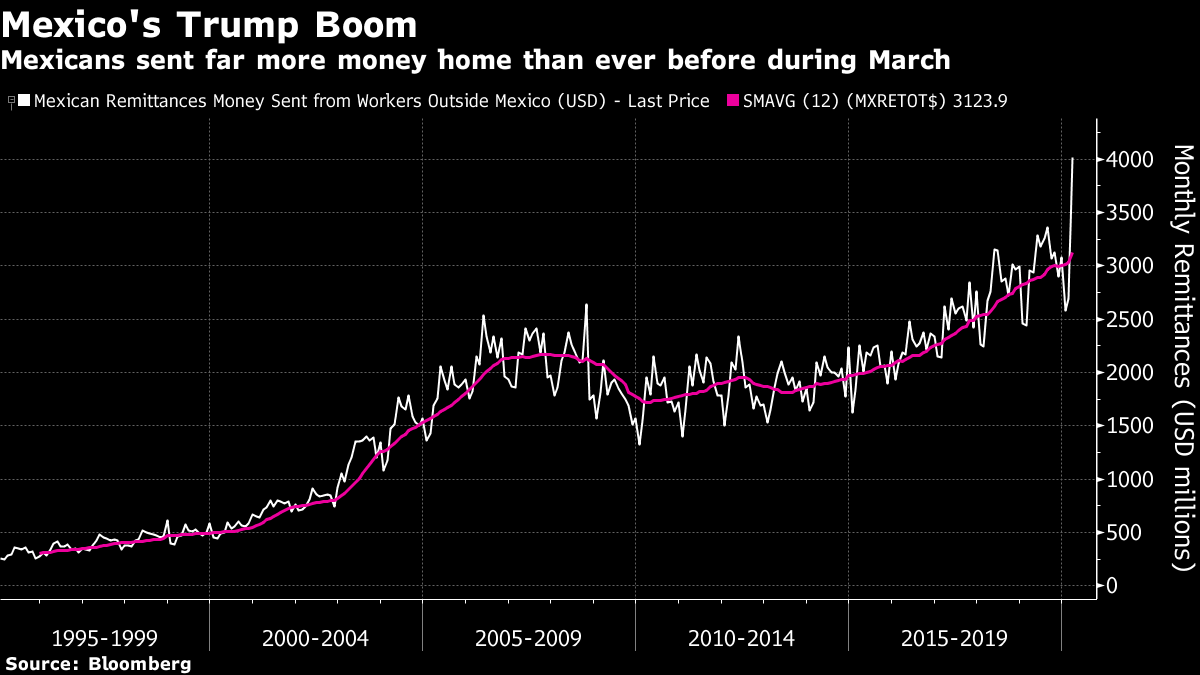

Eventually, narrow market breadth is always resolved the same way. Often, narrow rallies lead to large drawdowns as the handful of market leaders ultimately fail to generate enough earnings strength to justify elevated valuations and investor crowding. In these cases –such as the experience with the five largest stocks in 2000–the market leaders "catch down" to weaker peers. In other cases, improving economic outlook and strengthening sentiment help laggards "catch up" to the market leaders. In both cases, the relative outperformance of market leaders eventually gives way to underperformance. It's impossible to disagree. But Kostin also cautioned, correctly, that "timing the reconciliation is difficult." These are horrible conditions for active managers. Money Goes South Surprising statistic of the day: The amount of money Mexican migrant workers (almost all in the U.S.) send home in remittances has hit an all-time record. After staying flat through the eight years of President Barack Obama, remittances were already rising strongly under President Donald Trump. In March, the monthly total topped $4 billion for the first time, barely more than a year after reaching $3 billion:  How to explain this amid a sudden recession in which many migrant workers will have lost their jobs? In part, they are reacting to the exchange rate. With the peso falling to record lows, this is a windfall for their families. It's also possible that many are preparing to go home, and are getting their houses in order. There was a similar spike as the Great Recession was taking hold, followed by years of declines. The holders of some of the worst-paid jobs in the U.S. appear to think they are never getting their jobs back, and that the Mexican peso is badly undervalued. With any luck, their remittances will help to avert a crisis south of the border. Survival Tips There's always the sun. We have had good weather the last two days in New York, and it raises the spirits greatly to get some sunlight and fresh air, and maybe even turn your skin a little golden brown. The alert among you will have worked out from the hyperlinks that this is coming back to the 1970s new wave band the Stranglers, whose keyboardist Dave Greenfield died at the weekend, the latest high-profile victim of Covid-19. Any music from one's teenage years tends to live on strongly in the memory, but the Stranglers' oeuvre has stood the test of time. If I have a favorite, it is this song, written by Greenfield and performed on the BBC's Top of the Pops on the day after I turned 13. Try listening to the music of your youth; it will cheer you up. Get some sun and some fresh air. And rest in peace, Dave Greenfield. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment