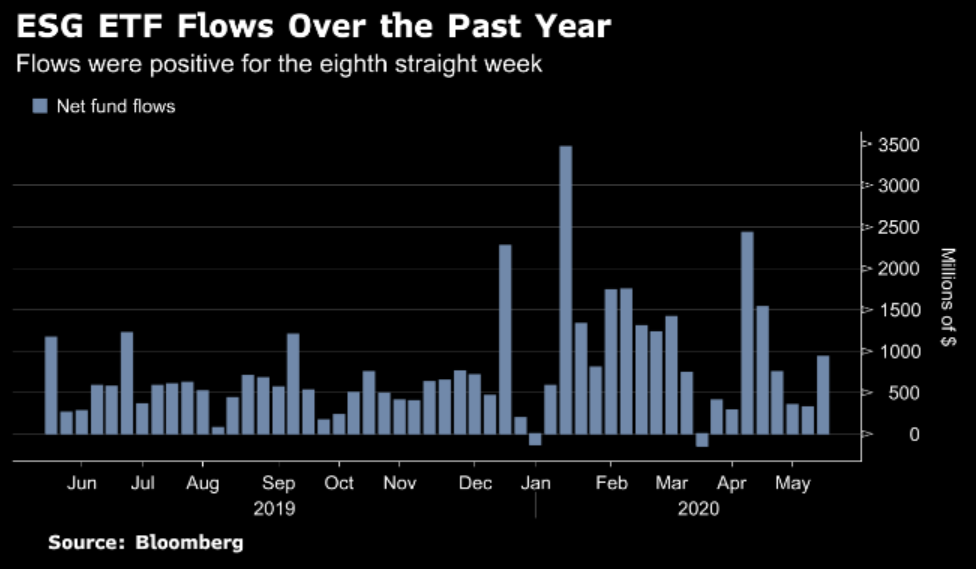

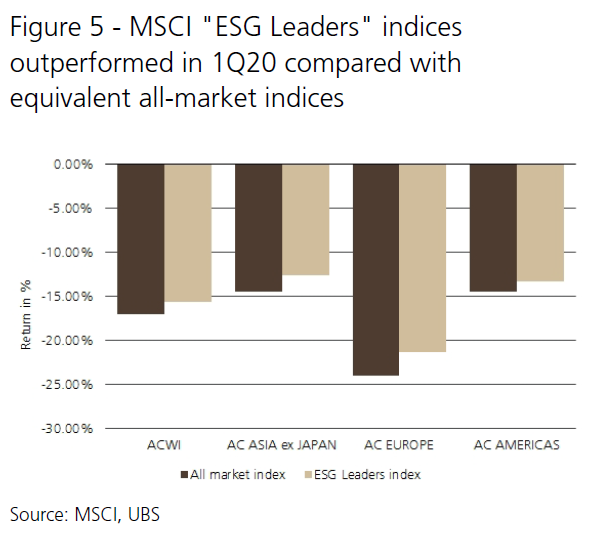

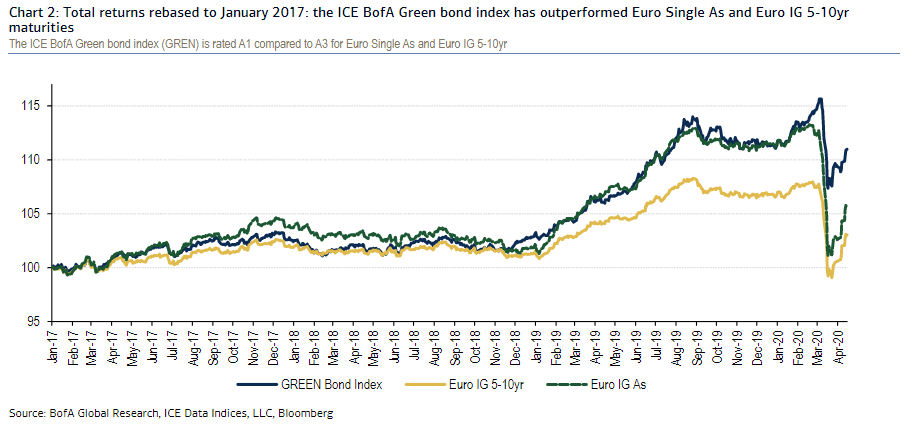

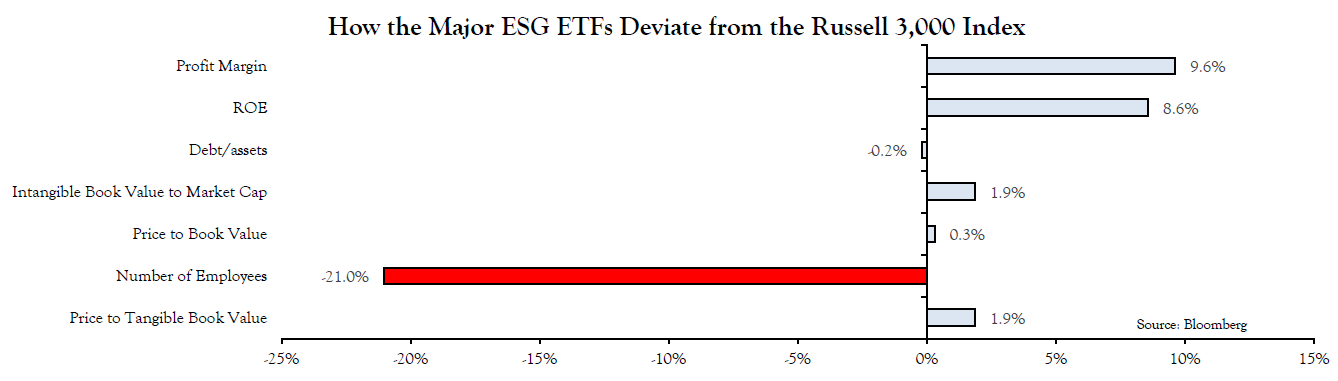

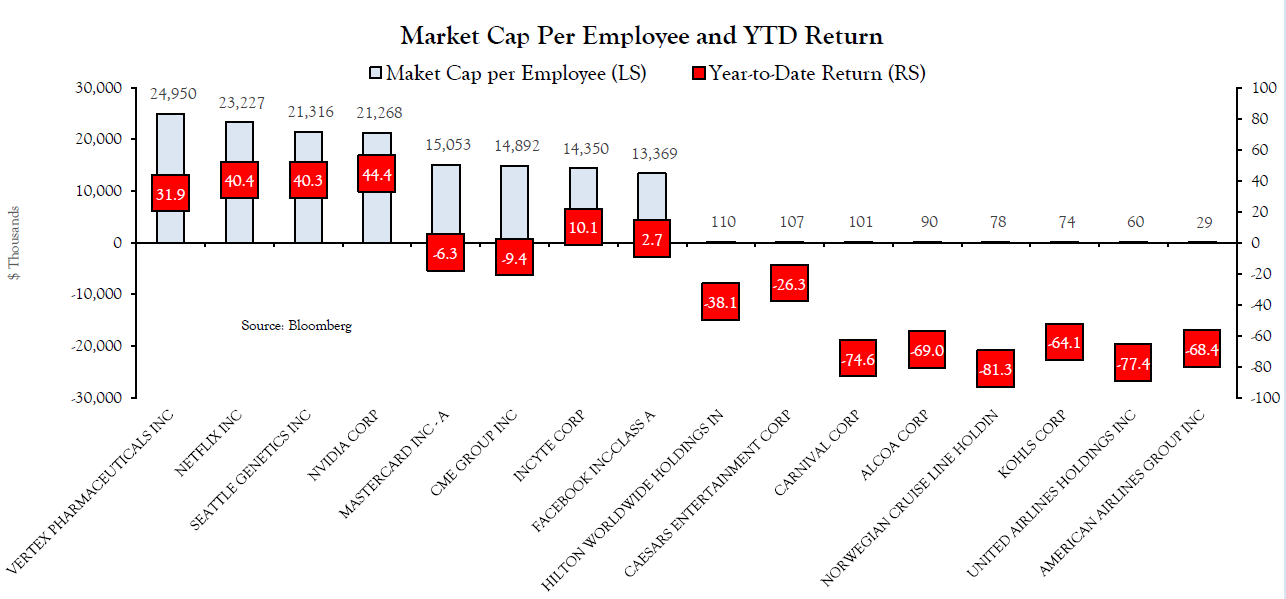

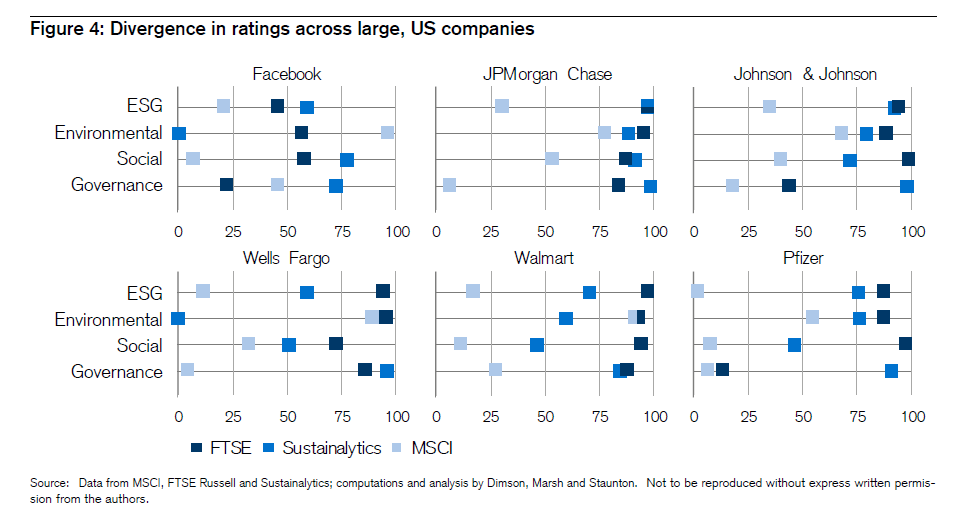

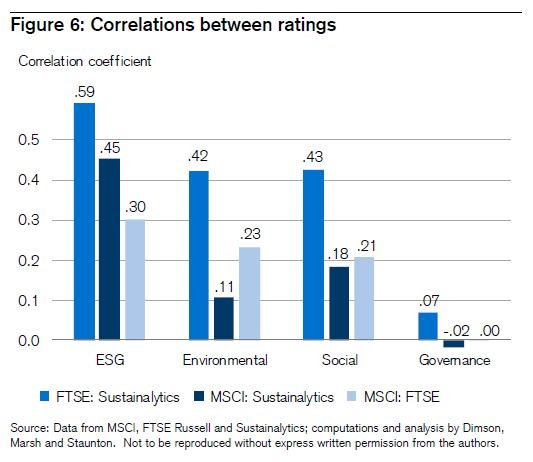

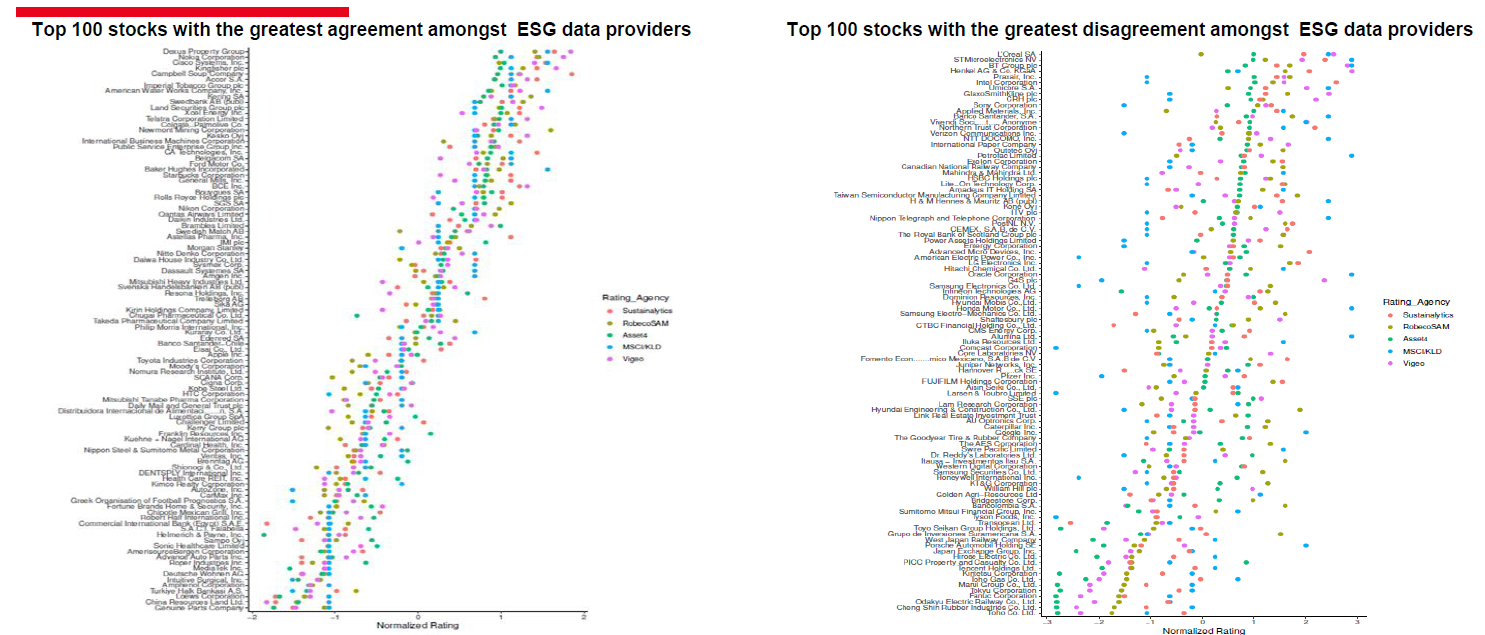

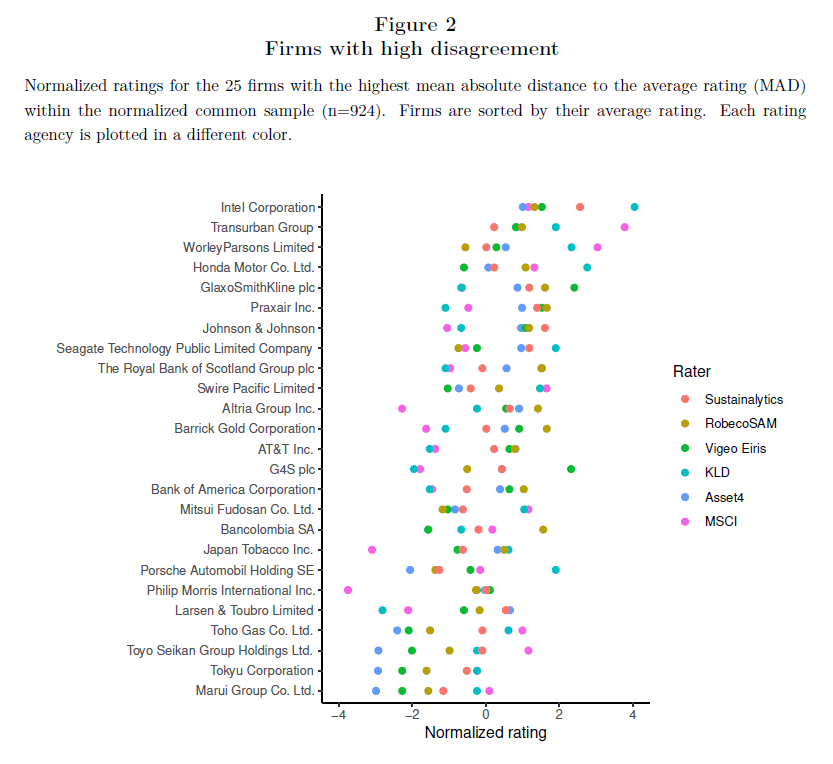

From Virtuous to Virtual Coronavirus has accelerated many investment and financial trends and ESG investing is among them. Environmental, social and governance investing has been in vogue for a while. The pandemic has taken it to the next level. This is how flows into ESG exchange-traded funds this year have moved, according to Bloomberg:  Amid all the horrors of 2020, ESG ETFs have so far suffered only two weeks of outflows, both of minimal amounts. Meanwhile, when it comes to investment performance ESG has also had a good crisis. Prices are down but in all the main regions of the world, MSCI's index of ESG companies outperformed the main benchmark during the first quarter, as this chart from UBS Group AG shows:  This isn't just an equity phenomenon. The ICE BofA Green Bond Index spent 2017 and 2018 performing almost exactly in line with equivalent euro investment-grade bonds. In crisis conditions, however, green bonds have come into their own:  There is a positive narrative to support this. In times like this, the story goes, companies that treat their staff and their surrounding communities well will be far better positioned to survive and prosper after the crisis. Corporate misbehavior is more unpopular than ever when so many people are hurting. And the clean air above locked-down cities will, some believe, give fresh impetus to attempts to reduce carbon emissions. There is, however, a more cynical or skeptical narrative. That starts with the basic point that ESG ETFs appear to be a watered-down version of growth funds. This chart shows the main iShares ESG ETF, which is ahead of the Russell 3000 index of large and small-cap U.S. companies, and far ahead of the value version of the index — but lags behind the growth version:  My Bloomberg colleague Kriti Gupta analyzed the tech and healthcare weightings in the main U.S. ESG ETFs, and discovered that indeed the ESG methodologies naturally favor those sectors — which have performed gangbusters this year:  For context, the current weighting of tech in the S&P 500 is 26.7%, while pharma and biotech account for 8%. Thus Kriti suggests that ESG's current popularity owes more to the fact that it offers a simple way to jump on the current hot stocks than to any greater desire to do good. That thought can be taken further, in a subversive direction. It is possible that ESG is undermining itself — or at least that the E and the S are in conflict with each other. Vincent Deluard, of INTL FCStone Inc., suggests that ESG funds are people-unfriendly. Tech and pharma companies tend to look good by ESG criteria, but they tend to be virtual as well as virtuous. These are the kind of companies that need relatively few workers and which churn out hefty profit margins. When Deluard looked at how the big ETFs's portfolios varied from the Russell 3000, the results were spectacular. They are full of very profitable companies with very few employees:  A further look at companies' market cap per employee showed that investing in the current stock market darlings who are making their shareholders rich is a very inefficient way to invest in boosting employment. They include hot names like Netflix Inc., Nvidia Corp., MasterCard Inc. and Facebook Inc. Meanwhile, the companies with the most employees per unit of market cap are like a rogues' gallery of those that have suffered from the pandemic, including cruise lines, airlines and department stores — all of which are known for employing lots of people:  The problem, Deluard suggests, is that ESG investing, intentionally or otherwise, rewards exactly the corporate behavior that is creating alarm. Companies with few buildings, few formal employees and a light carbon footprint tend to show up well on ESG screens. But allocating capital to them leads to a deepening of inequality, and intensifying the problem of under-unemployment. On the face of it, they aren't the companies that should be receiving capital if employment is to recover swiftly. If investors want to behave with the interests of "stakeholders" rather than "shareholders" in mind, and that is surely central to the ESG philosophy, then their current approach is directly counter-productive. No good turn goes unpunished. Defining Virtue ESG has another problem. How exactly is it to be defined? Any number of different financial data groups offer their own ratings, while a number of investment houses have created their own proprietary versions. That competition has created confusion. The following chart is drawn from the latest edition of the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook, compiled annually by the British academics Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton. It shows how three of the main rating services graded six big U.S. companies on the three main ESG factors, and overall. The divergences are staggering:  Looking at the broader universe of stocks covered by these three rating services, Dimson, Marsh and Staunton built the following list of correlations between them. There is worryingly little agreement over what constitutes a good company on environmental and social grounds; and almost no agreement at all on what constitutes good governance. A good rating from FTSE tells you nothing about what to expect a company's rating to be from Sustainalytics or MSCI, and so on:  Last year, before the coronavirus took over our lives, Florian Berg, Julian Koelbel, and Roberto Rigobon, three academics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, did another version of this exercise, with five different ratings services and a global universe of companies. Their results are summarized in this spectacular and beautiful chart produced by SG Quantitative. I apologize if it is initially impenetrable:  The chart on the left, which looks like a tornado and which might have a trend line fitted through it, shows the 100 companies with the greatest degree of agreement among the rating agencies while the scatter graph on the right shows the 100 companies with the greatest disagreement. The point is that the fit isn't that great even for the companies with the most agreement. To ram that home, here are the 25 firms on which the agencies have the most confident judgment, including some of the world's best-known corporations. Even here, the disparities are alarming:  The MIT study details how the divergences arise, but the problem is still to an extent intractable. The power of benchmarking to distort markets means that it is healthy to maintain a number of different agencies doing their best to find good metrics. While divergence is this great, though, it is unclear what exactly ESG investors are trying to achieve, and companies will be unsure what they need to do to improve their ratings. Competition should be healthy, but at this point, the variation is weakening the basic building blocks. It's less like choosing between two different indexes than choosing between rival versions of what a company's price-earnings ratio is. Another Day, Another FANG Statistic From ESG to another popular and proliferating acronym. At one point, the FANGs were just four companies: Facebook, Amazon.com Inc., Netflix, and Google (now part of Alphabet Inc.). After a great day for stock markets across the world Wednesday, the market capitalization of the four initial FANGs topped $3 trillion for the first time:  As of 2018, the gross domestic product of the U.K. was $2.83 trillion, according to the World Bank. But the acronymsters couldn't stop with just the FANGs. Apple Inc. and Microsoft Corp., even if they started in an earlier generation of tech, plainly belonged in their company. So, arguably, does the phenomenally successfully Nvidia. So this gives us the FANGMANs. And the seven FANGMAN stocks surpassed $6 trillion in market cap for the first time Wednesday:  Thanks to Holger Zschaepitz of Germany's Die Welt for this startling chart. Appropriately, the FANGMANs have long since overtaken the GDP of Germany, ($3.99 trillion in 2018). These companies are doing plenty of things right and providing valuable services. But what are the chances that they are going to be allowed to stay this big and this powerful? Survival Tips When the weather gets nicer and warmer, try to force yourself to get your work done during the daytime. Otherwise you might find yourself still working on your newsletter at 11:30 p.m., which isn't smart. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment