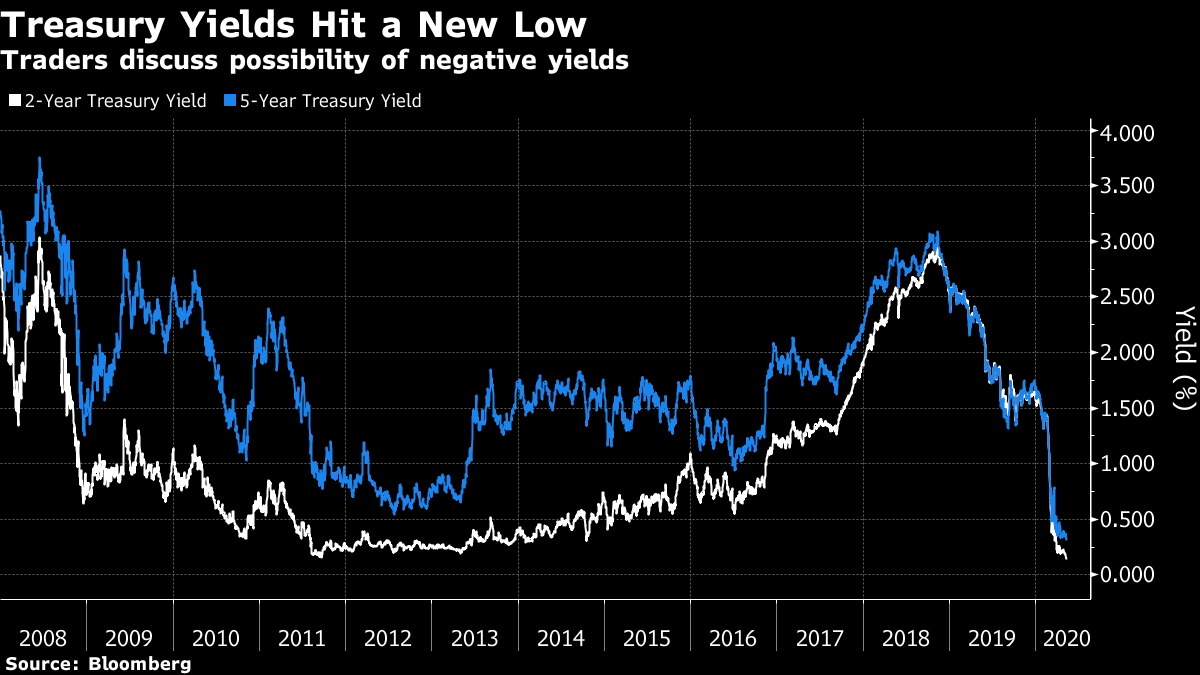

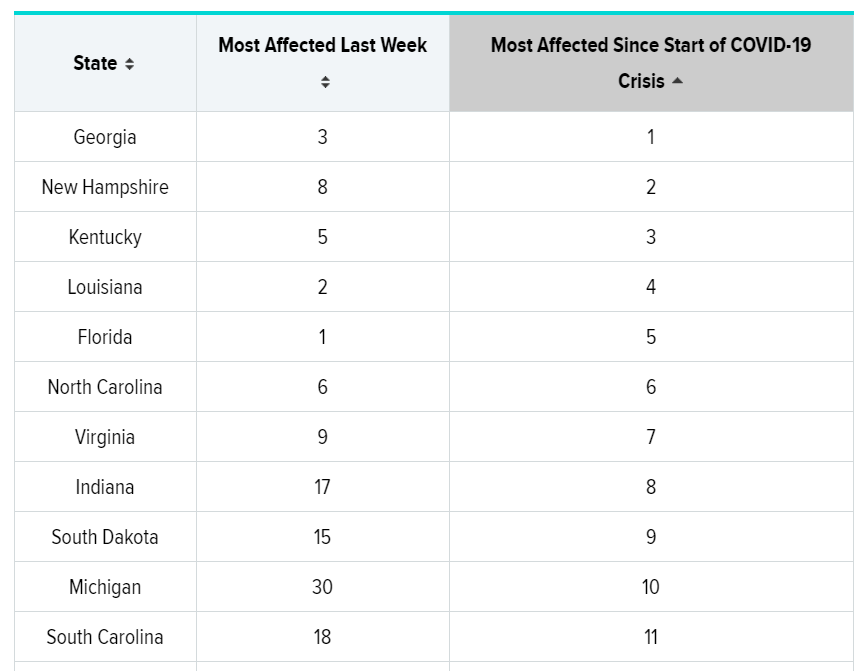

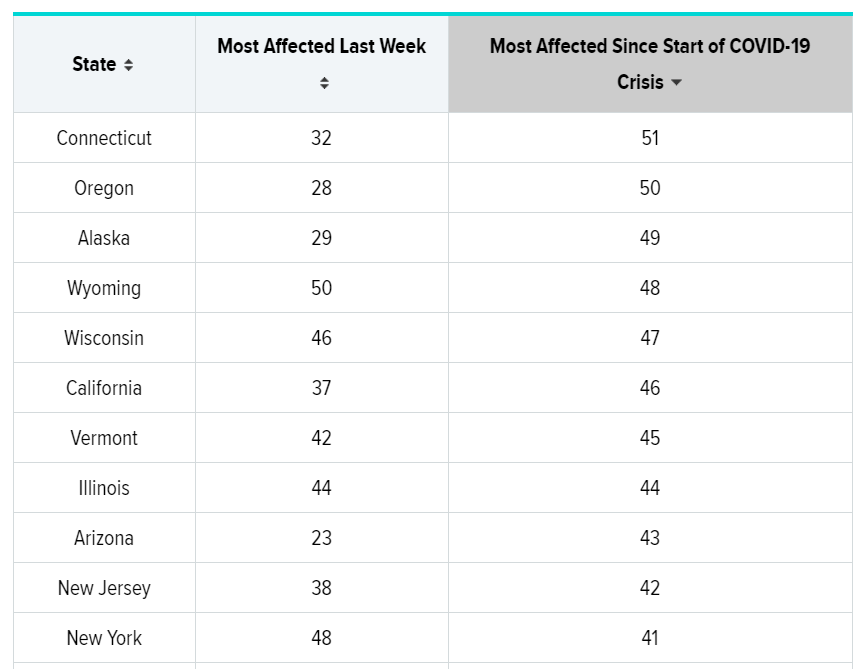

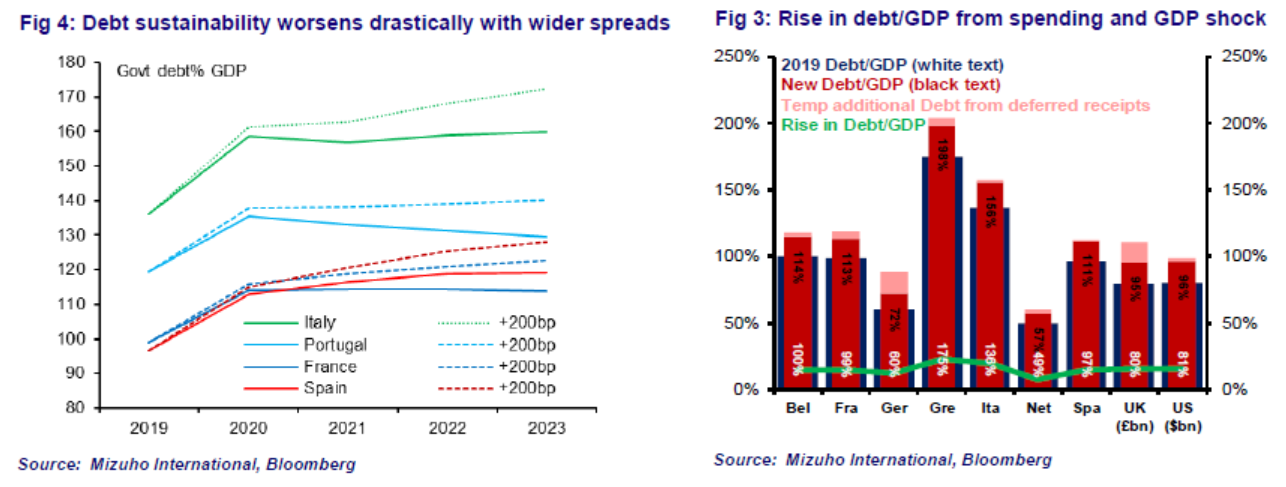

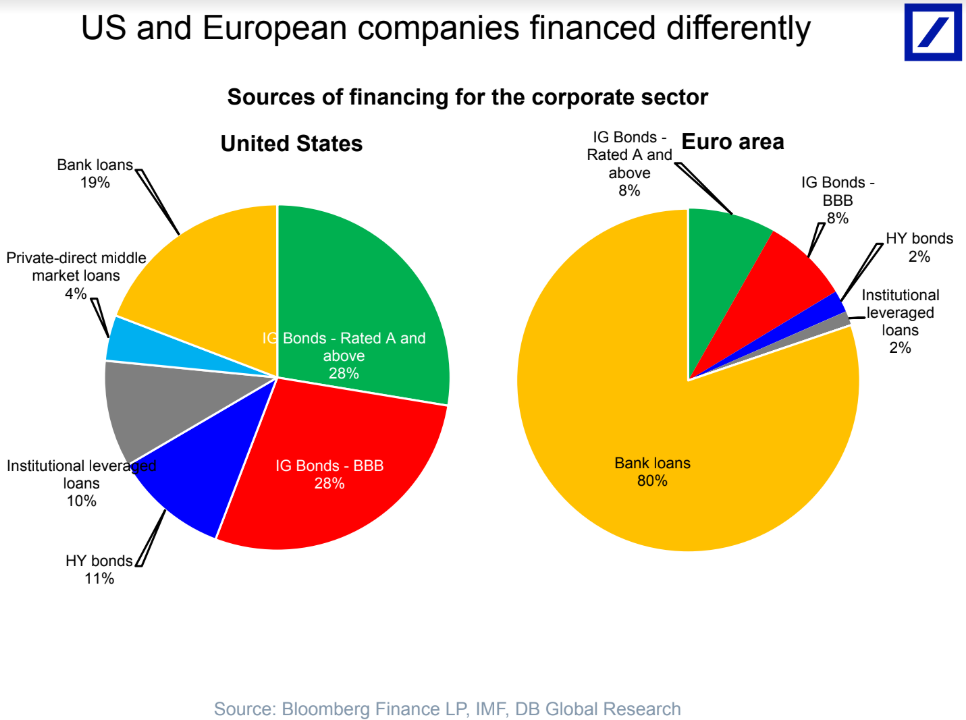

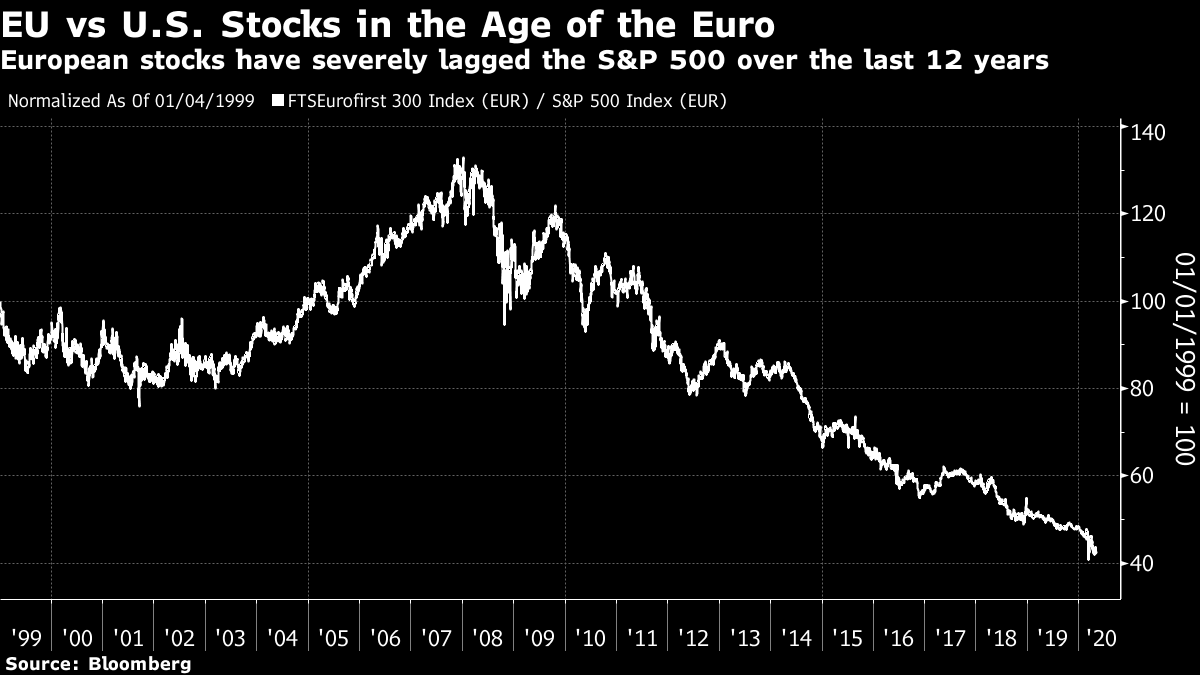

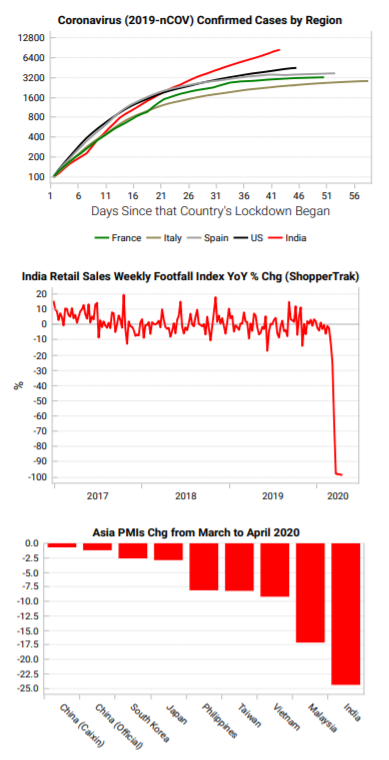

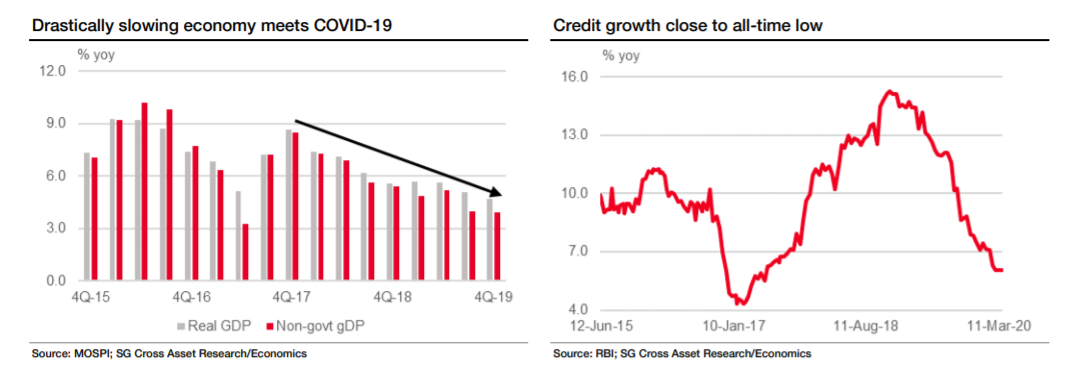

Creaking Federalism The United States of America has been a federalist nation for almost 250 years. Across the Atlantic, the European Union has been developing a federal group of nation states for almost 75 years. Both are finding difficulties that the coronavirus is posing problems for their federal models. Europe's is younger and much more incomplete, so it is finding the problems much harder. In the U.S., some of the rows over federalism have been soap operatic. The president's claim that he had "total" authority over the states when it came to reopening the economy was obviously false and soon withdrawn. The trial balloon by Mitch McConnell, Republican leader in the Senate, that states should be allowed to go bankrupt rather than receive any federal aid, also appears to have gone nowhere. Meanwhile, California's governor describes his territory as a "nation state," and New York Governor Andrew Cuomo complains that trying to acquire protective equipment is like bidding on EBay against 49 other states. All of this shows the tensions in federalism, without suggesting a true crisis is imminent. However, the differences between the federal and state governments, and between different states, have certainly contributed to the problems the U.S. is having in dealing with the virus. Amid the excitement in the stock market, note that two-year and five-year Treasury yields both hit all-time lows Thursday. That implies a serious belief that the Federal Reserve could move to negative interest rates. It is certainly hard to square with any belief that the U.S. is about to make a swift and painless return to economic business as usual:  The different approaches being taken by different states open the risk of a second wave of infections. This helps to explain why governors in several areas have formed groups to coordinate their actions — showing some of the problems with federalism right there. Meanwhile, the virus has exacerbated political divisions. The eight states with the highest death tolls are all "blue" (with the exception of Michigan, which now ranks as purple after voting for Donald Trump in 2016). The eight states with the lowest death tolls are all "red," with the exception of Hawaii. When we look at the economic effects of the lockdown, as seen in the percentage increase in unemployment insurance claims since the crisis started, we can see why the nation is beginning to look very divided. The states that have seen the worst increase are mostly red, according to a survey by WalletHub, a credit-scoring service owned by Evolution Finance Inc. None of the top 11 is regarded as a solidly Democratic state:  The list of those least affected, however, is dominated by blue states on the coast. Only the very sparsely populated Republican states of Alaska and Wyoming interrupt a list of liberal strongholds:  In New York City, where many can work from home quite easily, a continued strict lockdown seems obvious good sense. In states like Georgia or Kentucky, it must look far more contentious. And in the luckless state of Michigan, the only one near the top of the league tables for both coronavirus deaths and job losses, the problem of what to do next is appalling. Michigan is likely to be the single most important battleground for the presidency over the next six months. Thanks to the electoral college, a messy compromise adopted when the federalist model was first set up, it really matters who can eke out a plurality in that state — so we can see how the coronavirus is attacking American federalism at its most vulnerable points. Resolution of both the public health crisis and the economic crisis will be far harder as a result. But if American federalism has a problem, that is nothing to the difficulties for Europe. The coronavirus will make it much harder for the U.K. and the EU to thrash out a trade deal by the end of this year. Brexit is no longer what matters, though. Within the euro zone, the coronavirus attacked Italy and Spain first and with greatest virulence. Germany has been relatively spared. Some of this was bad luck for Italy, which suffered the first outbreak and had least time to prepare. Some is also down to demographics; Italy's aged population was the perfect environment for the virus. And some is the result of superior health policy. Germany's response does appear to have been exemplary. But this creates a serious problem. On the eve of the virus, the peril for the euro finally seemed over. Greek bonds were back where they were in autumn 2009, before the sovereign debt crisis broke out, and the spread of Italian over German bond yields had also returned to normal. Now, the possibility of a dissolution of the euro zone, which would make Brexit look like a piece of cake, has very much returned. Dealing with the economic damage caused by the virus requires aggressive fiscal policy. But the euro zone doesn't have a common fiscal policy. So a) either peripheral countries like Spain and Italy must do a huge amount of borrowing on their own account, bringing their credit quality and thus the integrity of the euro zone into question, or b) the euro zone must hammer out a common fiscal policy of a sort, perhaps through issuing "corona bonds." The problem is this requires a lot of difficult technocratic work in a hurry, and it implies that the relatively wealthy countries of the north should subsidize the poorer countries of the south. New York's Cuomo recently pointed out that much of the money paid by his wealthy state's taxpayers goes to help out places like Kentucky — but this has always been a difficult step for Europe to take. European leaders have failed to make any significant progress on corona bonds. Meanwhile, Germany's constitutional court has ruled that even the open-ended monetary policy actions currently being taken by the European Central Bank are against the constitution of its biggest member country. At a Bloomberg event Thursday, the ECB's president, Christine Lagarde, pointedly said that the central bank was answerable to the European parliament (and therefore, by extension, not to the German constitutional court), and pledged to continue to try to do what is necessary. But the net result is that the existence of the euro is once more in peril. George Saravelos, head of foreign exchange at Deutsche Bank AG, put it this way: The market is likely to respond very negatively to signs that Bundesbank participation in the Eurosystem is put at risk. By challenging [European Court of Justice] supremacy and creating a parallel legal order for the Bundesbank, the German Constitutional Court raises existential questions on the functioning of the ECB and, taken to the extreme, has ultimately opened a potential legal pathway for a German exit from the euro. This constitutional crisis needs to be urgently resolved. Uncertainty on this scale could be deathly. If Italy tries to borrow under its own steam, it is likely to do so at much higher spreads, and as Mizuho International Plc points out, that leads to serious problems. Greece is a much smaller country that has sustained much less damage from the virus; the central concern now must be Italy and its problematic relationship with Germany:  Those spreads are indeed widening again. They aren't at the levels seen during the worst of the crisis, when former Premier Silvio Berlusconi was ejected from office. Peter Chatwell of the cross-asset strategy team at Mizuho suggests that the spread of Italian over German bond yields will need to reach 500 basis points before politicians have the necessary political capital to force through some kind of settlement that rescues Italy. The process of getting back to such spreads would be very painful:  Europe also has to contend with its weak banking system. As this chart from Deutsche Bank's U.S. economist Torsten Slok makes clear, banks are far more important for Europe than they are for the U.S., so this is another serious problem:  The net result can be seen in the dreadful performance of European stocks since the euro was established on New Year's Day, 1999. This chart shows the FTSE-Eurofirst 300's performance since then, relative to the S&P 500, in euro terms:  Had the EU managed to take the opportunity to reform its creaky federalism after the ECB managed to stop the last sovereign debt crisis in 2012, things might be different. If it had made enough progress so that the EU's model of federalism was only as flawed as the U.S. version, its stock markets might at last be ready for a period of outperformance. As it is, the European model creaks even worse than its American counterpart. And so the long-suffering populations of Europe will have to undergo another crisis, and possibly even a traumatic split of the euro zone, before it can turn things around. India On the subject of unwieldy federal democracies — there are few if any countries flashing greater reason for concern than India. The world's second-largest country by population faces a risk of human catastrophe. The effect of its lockdowns so far appears to be severe on the economy, without yet limiting the spread of the virus. The following charts come from Variant Perception:  The lockdown appears to have succeeded in shutting down retail shopping almost completely, and massively reducing manufacturing activity, while failing (so far) to flatten the curve even as much as much as Italy, Spain and the U.S. had done at this stage. Added to this, the following research from Societe Generale SA — which is now predicting a slight contraction in real GDP for the year — indicates that the coronavirus has hit at a bad time, when Indian economic growth was slowing, and credit growth had declined sharply:  With the lockdown now being extended, these figures are concerning. There are two main readthroughs for investors. First, India may be the world's most important front in the battle against the coronavirus. If disaster can be avoided, that would provide a fillip for everyone else. Second, markets don't as yet register any great concern. India has been one of the stronger emerging markets for several years, since its recovery from the "taper tantrum" of 2013. Stocks sold off badly relative to other emerging markets in March, but have rebounded well. It doesn't look as though the most risky scenarios are yet in the price:  Survival Tips Let's try a little more listmania. The Guardian, wonderful repository of listicle journalism, now offers a countdown of the top 100 number one singles in the U.K. of all time. Is its list open to criticism? Well, Rod Stewart's Do Ya Think I'm Sexy? is somehow ranked at number 34. So there's your answer.

Stay safe and enjoy the weekend.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment