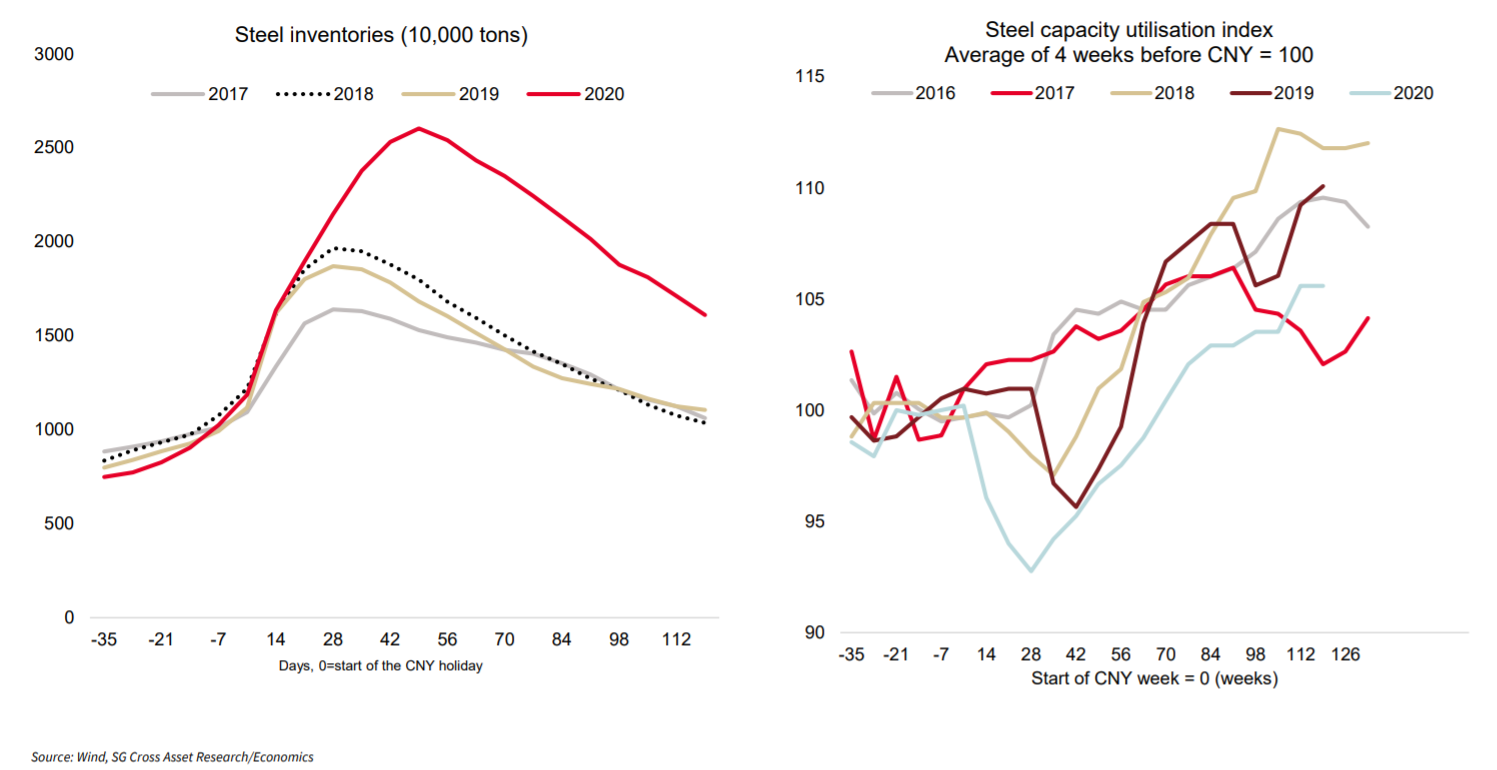

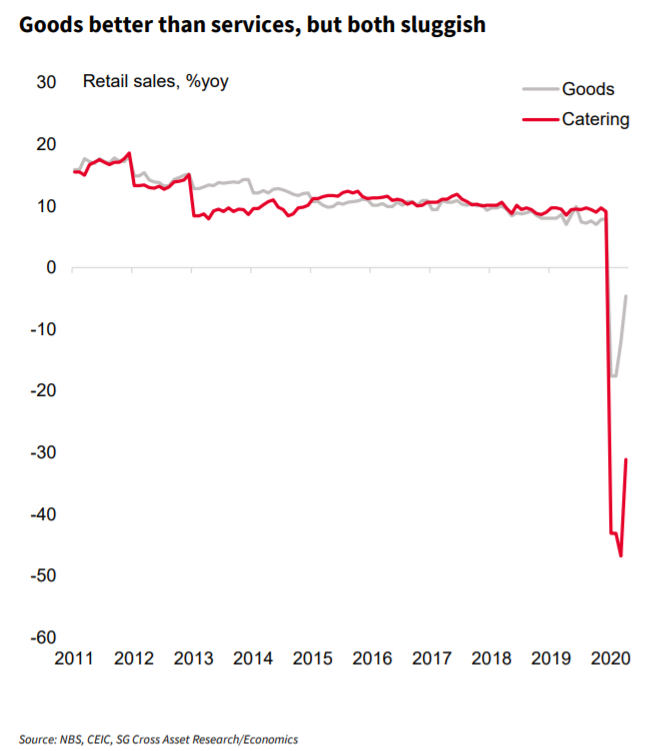

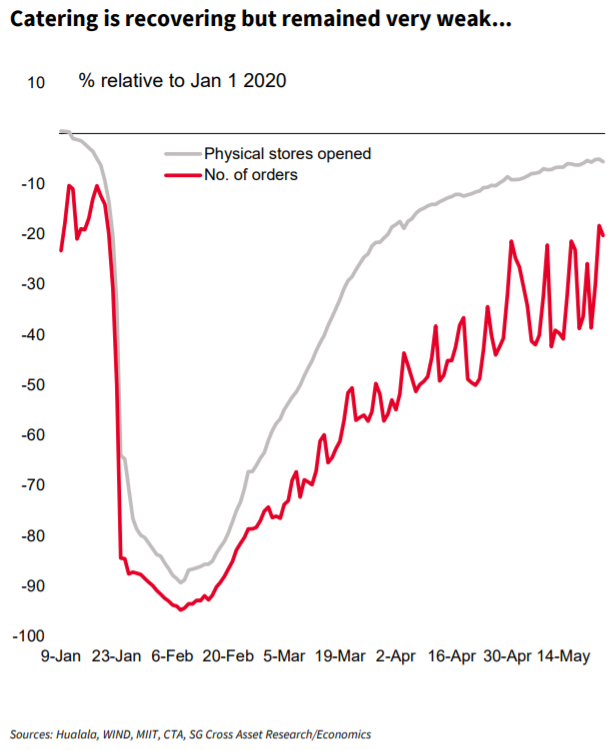

Waking Up to War It is never comforting to return from a long weekend to find headlines dominated by the word "war." But that is what the deteriorating relationship between the U.S. and China has created. What exactly do all these references mean? To end last week, China's foreign minister claimed that U.S. politicians were pushing the nations into a new "Cold War." That was followed by protests against a clampdown on Hong Kong security, with ugly scenes like these:  Markets hated this. Hong Kong has long basked in its position as the safest and most secure way to benefit from the explosive growth going on in mainland China. The sell-off in the Hang Seng Index at the end of last week has brought the market right back to earth:  For those following the market, the clashes amid the Hong Kong skyscrapers weren't even the clearest signal of provocative and ambitious Chinese intent. That came from the People's Bank of China's fix for the Chinese currency to start the week. This is the level the central bank sets as a guide for the market, and the exchange rate can vary from it by no more than 2% in either direction — it effectively tells the world how far China is prepared to allow its currency to move. And Monday's fix against the dollar was the weakest since 2008.  China left its currency fixed at an unrealistically weak level for several years after it acceded to the World Trade Organization in 2001. After 2005, it agreed on a swift appreciation, which halted in the spring of 2008 as the credit crisis took hold. In 2010 it was allowed to resume a steady climb. Since its shock devaluation in 2015, which caused a minor global crisis, the trend has been toward letting the currency weaken, particularly when China might want to send a message — as it did when the fix reached its previous post-2008 low in the days after the U.S. announced new tariffs on China in August last year. A weaker currency tends to make China more competitive, and makes life harder for U.S. exporters. So this can be seen as a very provocative gesture. Could China conceivably be prepared to let the yuan move all the way back to 8.0 per dollar? The shift in the currency followed a stiffening of the U.S. approach. President Donald Trump has barred a pension fund controlled by the federal government from buying or holding Chinese securities, opening a risk of broader sanctions by pension funds across the U.S. — which in the age of passive investing and exchange-traded funds can be done simply and cheaply. The administration has also announced the blacklisting of 33 Chinese entities over human rights violations. It had already barred U.S. manufacturers from supplying goods to telecom equipment manufacturer Huawei Technologies Co., on security grounds. To add to this, the conversation around the future for the global economy and financial system is ever more using the word "war." It is in the title of two books published this month, both by respected authors with a long history in finance and academe. First, there is Capital Wars by Michael Howell, who established CrossBorder Capital Ltd. in London:  Readers can also sample Trade Wars are Class Wars by Matthew C. Klein (now a commentator for Barron's and formerly a colleague at the Financial Times) and Michael Pettis of Peking University:  Both books are written by people whose prime interest is finance and the economy, rather than military history or wars. But both make clear that the current state of the global financial system does pose a threat to international peace. In this, they echo a rash of books over the last few years that drew comparisons between the U.S. and China and previous historic disputes when a rising power threatened an established hegemon, from Athens and Sparta through to Britain and Germany before the First World War. A great book by Harvard's Graham Allison also put the word "war" in the title, with a strong suggestion that it was inevitable:  Very few assets could provide shelter from an outright war between the U.S. and China. Such an event would be a disaster for everybody. Because of this, direct military conflict between the world's two biggest powers is unlikely — if not unthinkable. That helps to explain why there there has been no big sell-off of stocks or commodities in the last few days (outside Hong Kong) as the U.S.-Chinese relationship has deteriorated. Sabre-rattling serves the leaderships of both countries, evidently. A war would not. This might be too relaxed a response. The Covid-19 pandemic, which appears to have been mishandled by the administrations of both countries, amps up the tensions, and deepens dangerous imbalances within the global economy. Both the new books make clear that the root of the problem is that the U.S. and its dollar is no longer big enough to anchor the global financial system, but there is no obvious alternative. Instead, tensions within the two biggest economies are being expressed in conflict between them. Resolution can only come if both China and the U.S. get their own houses in order. For Klein and Pettis, as their title suggests, the conflict is between the wealthy, who hold capital, and the rest. Exporting capital to China has worked out well for the wealthy of both the U.S. and China, badly for workers in China, and dreadfully for workers in the U.S. In a very provocative comparison, they say that the U.S. and the West almost voluntarily allowed themselves to fulfill the same role that the colonies played for the old European empires, providing a ready source of demand for exports from the mother country (China). Unless both countries find a politically viable way to reduce inequality, the fault lines between them will deepen further. For Howell, the nature of the imbalance is different, although his theory appears consistent with that of Klein and Pettis. As he expresses it, the U.S. has an overdeveloped financial sector and an underdeveloped industrial sector, while China is the other way around. Fixing this involves risks and difficulty for those in power; China needs to financialize, so that it no longer needs to import American capital, while the U.S. needs to re-industrialize, so that it no longer needs to import cheap Chinese goods. It is very difficult for these things to happen unless they happen at once. Failing this, a "new Cold War" looms as one of the more likely and even sustainable solutions. The first Cold War didn't impede some impressive growth in the West, and even for a time in the Soviet bloc, and never became a direct "hot war," so this outcome isn't necessarily disastrous. Rather than a dollar-centric world, we could see a bipolar world, with China establishing some form of financial hegemony over Asia. This is themore or less explicit aim of China's Belt and Road Initiative. Meanwhile the Federal Reserve now has a list of 14 other central banks with which it offers liquidity swaps. That list looks, in Howell's phrase, a lot like an economic version of NATO. Natural U.S. allies such as Mexico, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand are included, as are Singapore and South Korea. China and Russia, to name but two, are not. The attempt is to isolate China. Historically, such divisions over capital have led to wars (although Britain's deciding to come under the U.S. umbrella without a fight is an exception). A new cold war, with two economic blocs that trade and invest ever less with each other, but can avoid bloodshed, wouldn't necessarily be so bad. Both leaderships might, however, aim for something better. Drastic measures by either nation to fix problems at home would help. Somewhat less drastic measures to cramp each other's style are more likely, and won't help. In the short term, as with so many things in life, what matters most is the economic impact of the virus. The risk is that the disease exacerbates the mismatch between the economies. And that looks possible. Since China began to reopen, its manufacturing sector appears to have returned to trend rather more swiftly than its consumer sector. Looking at the way the country is using steel, for example its manufacturers appear to be back on track, as shown in this chart from Societe Generale SA's cross-asset research:  Consumption is different. Retail sales are still running below their equivalent period of the year before, particularly in the catering sector, which finds it particularly hard to adapt to social distancing:  In catering, almost all stores have now reopened, but the number of orders is still significantly lagging:  The risk is that the coronavirus gives an incentive for China to keep pumping more out of its industry, and importing capital from the U.S., whose banking sector will be happy to provide it given lack of consumption at home. Whether it makes sense to call such a conflict a war over capital, or class, or trade, it would be damaging. For now, the coronavirus appears to have prompted both leaderships to take the easier alternative, and amp up confrontation. In the short term, markets might be able to continue to avoid the fight. In the longer term, meaning for long after there is a vaccine for the virus, it will be inescapable. Survival Tips This can double as a useful hint for anyone traveling to the U.K. once it's no longer riddled with coronavirus. Britons are apologetic by nature. If you haven't got anything to apologize for, find something. We can be quite forgiving; but failing to say sorry is unforgivable. In the U.S., Donald Trump has shown that a politician can go a long way without ever saying sorry. That's a much harder trick in England, as Dominic Cummings, the Svengali figure behind Brexit and the election of Boris Johnson as prime minister, demonstrated Monday. He explained why he broke the U.K.'s lockdown rules to drive 260 miles with his wife and four-year-old child while suspecting they were suffering from the virus. At no point did he apologize for this. Judging by the headlines in the Daily Mail (normally a stalwart voice of conservatism) and The Guardian (the traditional home of British liberalism), Cummings at least managed to unite the country on one issue. The absurdity deepened when Johnson subsequently did apologize for Cummings' actions. Cummings also broke another British political rule, which is never to make yourself look ridiculous. It is possible to recover from all manner of sins, but not from ridicule. So when he explained his decision to make another, half-hour drive, by saying he needed to test whether his eyesight was good enough to drive, the derision of the internet came down on him. It was a national holiday in Britain. People had time to produce some good memes, and they did. This was hilarious but it may yet have serious consequences. Persuading the British public to maintain social distancing will be much harder from now on. So first survival hint: When in Britain, never forget to say you're sorry. Second survival hint: If you're not sure you can see well enough to drive, don't go for a drive. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment