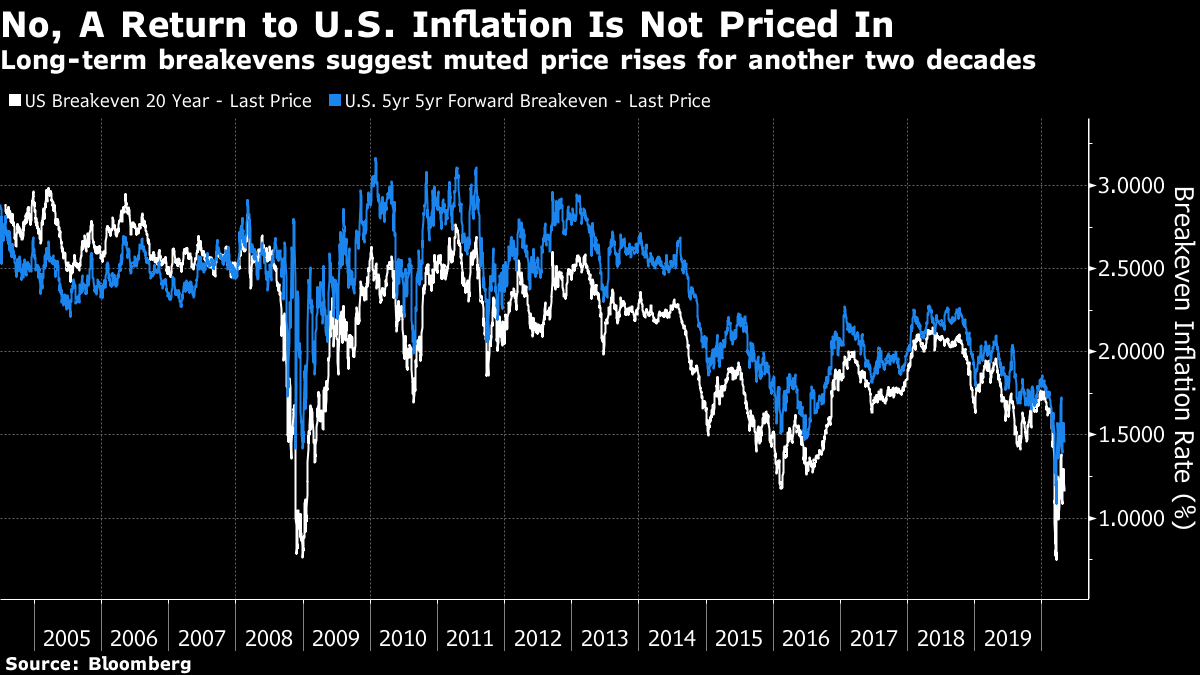

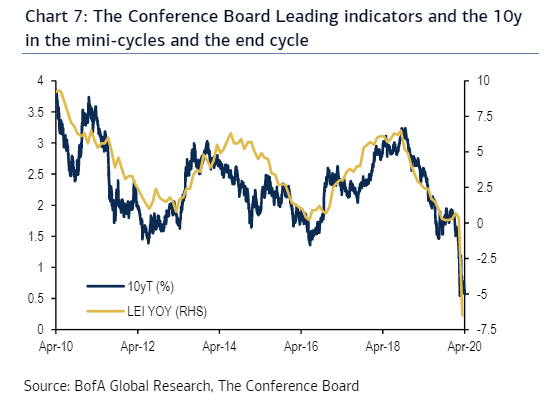

| "Whoever said money can't solve your problems must not have had enough money to solve 'em." So says Ariana Grande, and it appears that many in the markets agree. To the many who insisted that the sudden stop caused by the coronavirus was bound to bring a deep recession and an equity bear market in its wake, the response has been simple: Central banks have, or can create, enough money to solve the problem. And with interest rates as low as they are, governments can cheerfully borrow any extra. To paraphrase Ari slightly, those who see our problems as insoluble underestimate the powers that come with command of fiat money. You can indeed do a lot with fiat money, even drop it from helicopters. That is an eventuality that looks ever more likely, and the coronavirus has created the ideal circumstances. With business activity suddenly stopped due to an unavoidable external threat, if ever there were a time to create money and give it to people in need, it is now. Helicopter money creates intense issues. The most pressing is political control. Once people know that money can be bestowed so easily, politicians will suffer ever greater pressure to create more. Thus firm institutions are needed to control it, and those institutions don't yet exist. This was probably the strongest argument made against Frances Coppola when she defended her book "The Case for the People's Quantitative Easing" in a Bloomberg book club live chat last year. But the most fundamental issue is inflation. For a generation, rising price levels haven't been a significant problem in the developed world (yes, asset prices and services such as education and healthcare are exceptions). By the Federal Reserve's favored PCE measure of inflation, excluding fuel and food, price levels have been remarkably stable within the current target range of 1% to 3%. Inflation dipped below 3% in 1992 and has never exceeded it since; it dropped below 1% only slightly and briefly during the Great Recession:  This leads to a problem of imagination. Nobody much under 50 has any clear memory of what it's like to deal with inflation as a serious problem. But as Dario Perkins of TS Lombard points out, governments have adopted a wartime response of huge fiscal spending, and in the process are "diluting the anti-inflation bias they built into macro policy institutions after the 1970s." That may not immediately lead to price spirals, but it does suggest a possible "fire regime" to replace the era of Japan-style ever-lower growth, inflation, and yields that Albert Edwards, the famously bearish investment strategist at Societe Generale SA, has called the "ice age." We also have the experience of the last decade, when the extraordinary asset purchases by central banks were denounced as inflationary, and the gold price soared in the years immediately after the crisis – only to subside as deflation remained obdurately more likely than inflation. And indeed the bond market shows no risk whatever of a return to inflation. This chart shows the 20-year breakeven (the implicit average inflation rate over the next 20 years) and the five-year/five-year breakeven (which avoids any distortion from the very near future by looking at the implicit five-year forecast for inflation starting five years from now):  Some of this may be explained by the market's response to the collapse in oil. In the very short term, oil has a huge impact on breakevens as it is a big part of inflation baskets. This should cancel out over 10 years, but as this chart from BofA Securities Inc. makes clear, oil tends to lead expectations well into the future:  Crude prices reflect demand pressures — which may have broader consequences — but also supply effects, which should be more specific to the oil industry. This latest fall was largely led by a supply shock when OPEC+ discipline broke down in March, so it isn't clear that this tells us much about future inflation. That leads to the possibility of a failure of imagination. Over the last decade, inflation expectations have correlated almost perfectly with leading indicators for economic growth, as shown by another graph from BofA:  This seems a natural correlation these days, but 'twas not ever thus. In the 1970s (before the great majority of people currently responsible for allocating capital had finished their formal education), poor economic prospects used to coexist with higher inflation. The developed world has been cured of stagflation for almost four decades now, and the market collectively appears totally confident that this will continue. The experience of 2008, when a big hit to markets and then the economy proved deflationary, reinforced this belief. Could stagflation return? And why would inflation reappear this time when it didn't after the similar desperation tactics of 2008? There are broadly four answers (summarized beautifully by Chris Watling, founder of Longview Economics in London). - After the GFC, governments responded with austerity. That isn't going to happen this time. Politicians have grasped they will need to try to revive the economy, even at the risk of a growing deficit. A decade ago the Tea Party movement was arguably motivated at first by opposition to fiscal irresponsibility. Any populist pressures this time around will be in a completely different direction. If governments are actually going to spend money, inflation becomes far more plausible.

- Fiscal stimulus this time is being directed straight at people's wallets, at least in the U.S. Meanwhile, measures by governments across the Western world to keep paying a decent proportion of people's wages while quarantine constricts their spending should mean a lot of people with significant cash piles and a big incentive to spend them.

- As we were told in Economics 101, there is both "cost-push" and "demand-pull" inflation. With many suffering through a major economic shock, there is no demand-pull at present — although it remains a possibility post-quarantine or post-vaccine. But cost-push appears already to be with us. Interrupted supply chains make it more expensive to get goods to consumers, meaning that costs have to be passed on in higher prices. Reduced supply also leads to higher prices. The worries about meat shortages should be a foretaste of wider problems.

- Finally, there is deglobalization. We saw some of this a decade ago, but not as much as many had feared. Few countries attempted to raise tariff barriers and China's growth helped the world pull through. Nothing like this is going to happen this time around. The simple decision by many governments that they are over-reliant on countries a long way away for vital supplies will lead them to find local alternatives. These will be more expensive, fueling inflation.

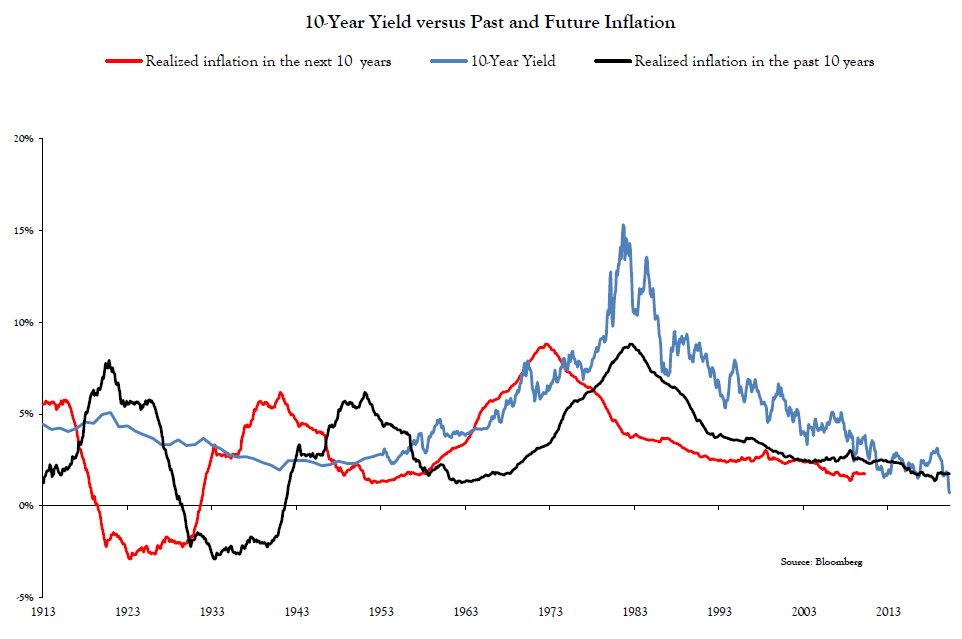

Add the risks that helicopter money, once started, could be politically impossible to stop, and you have a very sound case for future inflation far in excess of what the market is currently predicting. Is it wise to bet against the bond market? No, not always, but it is hard to find much relationship between bond yields and subsequent inflation over history, as this chart from Vincent Deluard, global macro strategist for INTL FCStone Financial Inc., shows:  How can we deal with this? Inflation effectively acts as a brake on government borrowing. The higher the expected rate, the more investors will demand when governments issue a bond. If austerity isn't going to happen, that implies financial repression will be needed — forcibly keeping bond yields low, or effectively forcing people to lend to the government at uneconomic rates. Central banks are already girding themselves for true "yield curve control," and there are precedents. To quote Joachim Fels, economic adviser to Pacific Investment Management Co.: There is a precedent in modern history for how this can be done: Following World War II, the Fed kept in place a lid on long-term Treasury yields (at 2.5%) that had been originally implemented when the U.S. joined the war. Thus the Fed helped keep government borrowing costs low during the post-war economic boom and high inflation. With nominal GDP significantly exceeding the nominal interest rate on the public debt, the debt-to-GDP ratio deflated without harmful consequences for the real economy. Under stagflation, neither stocks nor bonds do very well, for obvious reasons. Judging by the 1970s, when prices of both oil and gold went ballistic, the time could be right for another wave of higher commodity prices. As for financial repression, inflation might be stoppered up somehow, but the effects on economics and investment would still be significant. A repressed economy in which the government is more active tends to be less dynamic. Sectors particularly prone to governmental interference might be worth avoiding. Of course it remains possible that the recession inflicts such a lasting shock to demand that the inflationary forces can still be contained. But that isn't a positive prospect. Coming back to Ariana Grande, it is just possible that governments do have enough money to deal with deflation — in which case inflation remains the big risk for which investors aren't yet positioned. Survival Tips Now for some more of My Favorite Things. The original song from "The Sound of Music" is rather trite, but Ariana Grande isn't the only musician to have made something more interesting out of it. It was very much the signature tune of the great saxophonist John Coltrane. I found a clip from 1965 of his quartet (all of whom have now sadly left us) playing the song here. This particular song sticks in my mind because it started one of the most difficult classes I ever took. At Columbia Journalism School's book-writing class, presided over since its inception by a great professor called Samuel G. Freedman, the object is to write a book and get it published. Anything less is not a total success. It was therefore imperative for all of us to get the message swiftly that we were going to have to work incredibly hard. To open the class the professor played us Coltrane's My Favorite Things while showing us pictures by the young Picasso. Coltrane was an obsessive hard worker, who to the end of his short life would practice for many hours each day, working again and again on scales and difficult transitions. Picasso was an accomplished draftsman, who spent many years in his youth mastering the skills of his craft and producing artwork that was great but in no way avant-garde. Brilliant extemporization and excitement, and deliberate transgressions of well-established artistic form, can only come from those like Coltrane or Picasso who have worked, and worked, and worked, to master the basics first. That was the message the aspiring book-writers at Columbia had to learn, and it still resonates for me every time I hear a recording of Coltrane playing My Favorite Things. In New York City we have now reached Day 50 since the schools closed. I am finding it harder and harder to use the time in quarantine to get anything done, and I gather many others feel the same. If any of us ever want to do anything as well as Coltrane played the saxophone, maybe we should take the opportunity to put in some practice. Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment