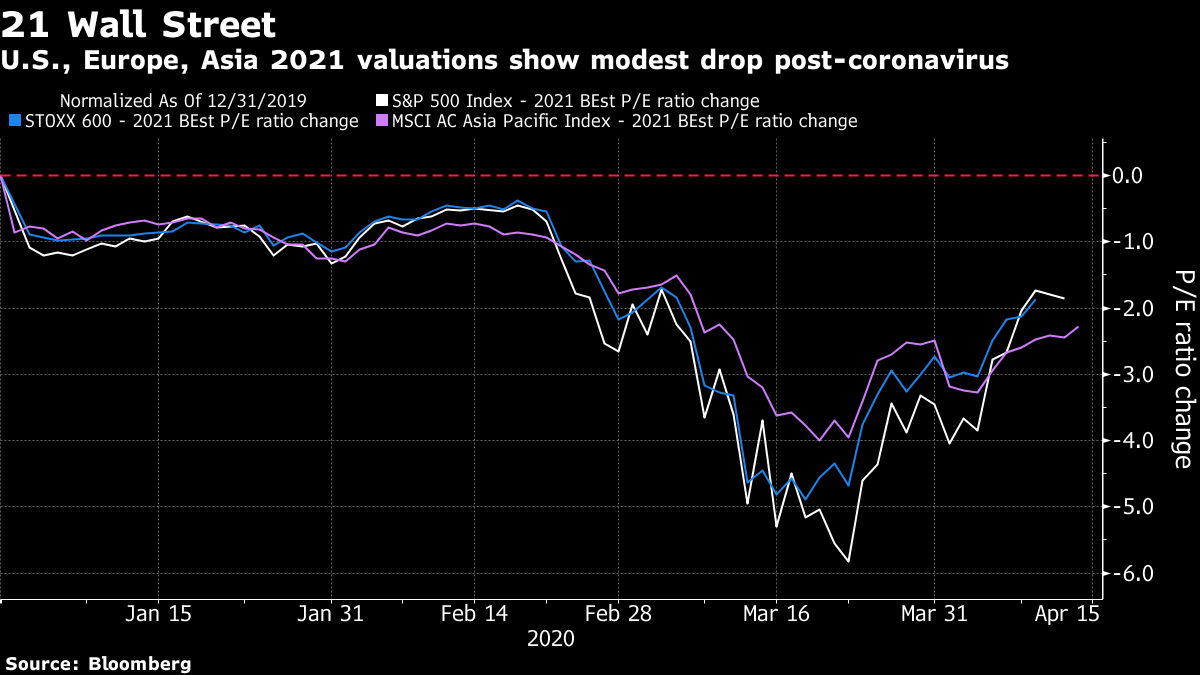

| The "Great Lockdown" recession will be worse than 2009, according to the IMF. Trump halts U.S. funding for the WHO. And once again, deflation is threatening to engulf Japan — but this time it's thanks to the oil price crash. Here are some of the things people in markets are talking about today. The International Monetary Fund says the "Great Lockdown" recession will be the steepest in almost a century and warned the world economy's contraction and recovery would be worse than anticipated if the coronavirus lingers or returns. In its first World Economic Outlook report since the spread of the virus and subsequent freezing of major economies, the IMF estimated on Tuesday that global gross domestic product will shrink 3% this year. That compares to a January projection of 3.3% expansion and would likely mark the deepest dive since the Great Depression. It would also dwarf the 0.1% contraction of 2009 amid the financial crisis. The fund anticipates growth of 5.8% next year, which would be the strongest in records dating back to 1980, but it cautioned risks are tilted to the downside. Much depends on the longevity of the pandemic, its effect on activity and related stresses in financial and commodity markets, it said. And if you were pinning your hopes on a V-shaped recovery? It seems more unlikely than ever, after the institution said output in both advanced and emerging markets would undershoot their pre-virus trends through 2021. Asian stocks looked set for a muted start to trading as investors scoured earnings reports for evidence of the impact of the coronavirus outbreak. The dollar retreated and U.S. equities advanced, while futures pointed to modest gains in Japan, Hong Kong and Australia. The S&P 500 jumped to a one-month high while giant technology stocks pushed the Nasdaq 100 through its 50, 100 and 200-day moving averages. Johnson & Johnson surged after posting stronger sales and boosting its quarterly dividend. JPMorgan and Wells Fargo slumped as their profits were hit by major provisions. Treasury yields slipped. Elsewhere, oil slumped as plunging demand and a massive supply glut pushed aside the supply deal between the world's largest producers, and gold was little changed. U.S. President Donald Trump will temporarily halt funding to the World Health Organization, following up his claims that the international body has failed to share information about the coronavirus pandemic. "The WHO failed in its basic duty and must be held accountable," Trump said Tuesday. Meanwhile, U.S. airlines reached preliminary agreements with the Treasury Department to access billions of dollars in aid. Leaders across Europe are weighing steps to exit quarantines, with Denmark set to reopen day care centers and primary schools. Spain, Germany and Italy all reported fewer infections, suggesting the crisis continues to ease. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, on the other hand, has extended a nationwide lockdown through May 3. And as the number of new Covid-19 cases each day begins to slow in parts of the U.S. and states consider rolling back social-distancing measures, a huge unknown remains for scientists: Who has become immune to the disease — and for how long? Meanwhile, two of the world's biggest vaccine makers — Sanofi and GlaxoSmithKline — are joining forces to tackle the virus as the number of confirmed infections approaches 2 million worldwide. Here's how Bloomberg is mapping the outbreak. Once again, deflation is threatening to engulf Japan's economy. But this time, it's because of sharply cheaper oil, which is draining price momentum from an economy battered by the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. Lower energy prices may push inflation below zero as early as April, according to Bloomberg News calculations. The return of falling prices in a rapidly contracting economy could not only buckle a cycle of weak upward momentum, it could reverse it, leaving Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the Bank of Japan with nothing to show for their unprecedented campaign to slay deflation. Becoming the first Group of Seven economy to slide back into falling prices also highlights the risk to the global economy of the oil shock and virus crisis triggering a wave of downward pressure on inflation across the world. Meanwhile, a researcher at China's biggest oil company is putting forward an interesting take on the price crash: The country's drillers should copy the hedging strategies of Mexico, which use financial derivatives to protect against falling oil prices. And the supply war looks far from over: Saudi Arabia might have just signed off on one of the most notable oil output deals in history, but they slashed its official selling prices to Asian customers for May by larger-than-expected margins this week. With the biggest U.S. banks facing an unprecedented economic standstill and new accounting rules, most analysts expected them to double what they set aside for bad loans a year ago. Those predictions weren't nearly pessimistic enough. Both JPMorgan and Wells Fargo posted their highest loan-loss provisions in a decade, setting aside more than $12 billion to cover defaults across the economy, but especially from credit-card borrowers and oil companies. Banks faced criticism in the last crisis for being slow to recognize the coming pain, and Tuesday's results show they intend to avoid that this time. "This is the reality check," Credit Suisse bank analyst Susan Katzke wrote after JPMorgan's results. "More to come." JPMorgan's profit fell 69% to the lowest in more than six years, even as the firm's traders seized on record volatility to deliver their best quarter ever. Wells Fargo posted earnings of 1 cent per share, down from $1.20 a year earlier. Shares of both banks slipped in New York trading at 11:58 a.m. as the broader market rose, with optimism the pandemic is slowing driving up the S&P 500 more than 2%. JPMorgan slumped 3.7% and Wells Fargo was down 4.4%. What We've Been Reading This is what's caught our eye over the past 24 hours. And finally, here's what Cormac's interested in this morning Before one of the foggiest earnings seasons in history, the word coming back from Wall Street is that equity bulls are writing off this year and anchoring their investment decisions on 2021 forecasts instead. That makes sense, so let's take a look at where those valuations are now compared to where they were before the coronavirus hit. With the usual caveat that estimates are constantly being revised, U.S. stocks are trading on 16.1 times forecast 2021 earnings compared to 18 times at the beginning of the year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. European shares are on 13 times versus 14.9. Asian shares show the biggest impact from the coronavirus, trading on 11.7 times versus 13.4 times at the start of this year. Leaving regional variations aside, there has been just a modest drop in valuations from the greatest global pandemic in over 100 years.  If you think the corporate world will bounce back to the same place it was in December 2019 quickly, then you likely still see an attractive opportunity in stocks, especially in Asia. But if you believe there is a risk of a long-term hit to corporate margins as the impact of the pandemic becomes clearer, the valuation discount may not be great enough given the increased uncertainty and risk of further estimate cuts. Cormac Mullen is a cross-asset reporter and editor for Bloomberg News. For the latest virus news, sign up for our daily podcast and newsletter. |

Post a Comment